About this course:

The purpose of this course is to ensure that APRNs understand various conditions of the throat, including group A Streptococcus, and how to manage the care of patients suffering from sore throats.

Course preview

Upon completion of this activity, the APRN should be able to:

- Consider common causes of acute pharyngitis (sore throat).

- Review the occurrence of pharyngitis in the US.

- Identify risk factors for the various types of pharyngitis.

- Examine the current diagnostic standards for the various types of pharyngitis.

- Identify appropriate treatment and follow-up for various types of pharyngitis.

- Summarize the best practices for preventing various types of pharyngitis in pediatric and adult populations.

- Discuss potential complications for the various types of pharyngitis.

Acute Pharyngitis

In a retrospective analysis from 2011-2015, Luo and colleagues (2019) noted that approximately 15 million healthcare visits per year are attributed to acute pharyngitis. The incidence of acute pharyngitis peaks in childhood/adolescence; about half of all cases occur before age 18. The incidence amongst adult patients declines after age 40 (Chow & Doron, 2020).

Several viruses and bacteria can lead to acute pharyngitis, but a common cause is Streptococcus pyogenes (GAS), also known as group A Streptococcus or group A strep. This bacterium can live on human skin and in the throat without causing illness, also known as colonization. Infected or colonized individuals are the source of nearly all infections. GAS is a significant source of community-acquired strep throat (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2018c). GAS is the most common bacterial cause of acute pharyngitis; it is responsible for approximately 5% to 15% of adult and 20% to 30% of pediatric cases of acute pharyngitis (Luo et al., 2019). In the US, the estimated costs due to GAS infections are between $224 and $539 million annually (Banerjee & Ford, 2018).

The direct and indirect costs of recurrent infections include medical visits, medications, and the loss of work and school for the child and their caregiver(s). Misuse of antibiotics for viral pharyngitis or overuse of antibiotics for GAS can lead to resistant organisms. Many children with recurrent episodes of GAS pharyngitis may have indications for a tonsillectomy, as this is one of the two most common reasons for this procedure (Mitchell et al., 2019). This module will explore the best practices and recommendations for viral, GAS, and other common types of pharyngitis.

Viral Pharyngitis

Pathophysiology

Roughly 25-45% of acute pharyngitis cases are caused by respiratory viruses (Chow & Doron, 2020). Several different viruses can cause pharyngitis, including rhinovirus, coronavirus, Epstein-Barr virus (causing mononucleosis), influenza A or B (flu), HIV, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, coxsackie A viruses, enteroviruses, and herpes simplex. The viruses are spread easily from sneezes or coughs, which cause the expulsion of viral droplets out into the surrounding air. The droplets from an infected person’s nose or mouth can directly contact mucous membranes or adhere to unwashed hands, making their way to the mouth, nose, or eyes when the individual touches them. The virus invades the pharyngeal mucosa along the back of the tongue, the roof of the mouth, and the tonsils. The localized tissue invasion causes inflammation (see Figure 1) and excess secretions, leading to throat irritation, which is worsened by nasal secretions (Fleisher, 2020; Harvard Health Publishing, 2020). Herpes simplex is caused by either HSV-1 or HSV-2, although HSV-1 is more commonly found orally. Recurrences and subclinical viral shedding are more frequent with HSV-2. These viruses may be spread through close personal contact as well as through unprotected sexual contact (CDC, 2015).

Risk Factors

Viral pharyngitis causes between 50% and 80% of pharyngitis cases annually among children and adults. The peak season for all types of pharyngitis is usually winter and early spring. Most types of pharyngitis also have similar risk factors, including age (children and teens at highest risk), close living quarters (viral and bacterial infections spread more readily in areas where people gather such as schools, daycare centers, offices, or airplanes), compromised immunity (due to HIV, diabetes, steroid therapy, chemotherapy, stress, poor diet, or fatigue), and irritants such as:

- Tobacco (both smoking and secondhand smoke increase the risk of viral or bacterial infection);

- Allergies (seasonal allergies or allergies to animals, dander, or molds);

- Chemicals (particles from burning fossil fuels and common household chemicals);

- Chronic sinus infections (drainage from the nose; Mayo Clinic, 2017).

With any irritation, the pharyngeal mucosa is left vulnerable to viruses and other microorganisms to invade (Mayo Clinic, 2017). Recent immigration from an underdeveloped country or lack of vaccination is a risk factor for diphtheria infection. Protective factors should include decreasing stress, eating a healthy diet, getting adequate rest, and avoid exposure to smoke and chemicals (Mayo Clinic, 2017).

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms associated with viral pharyngitis may include:

- Itchy or painful throat;

- Pain that increases with swallowing (odynophagia);

- Swollen, red tonsils;

- Hoarse or muffled voice;

- Fever (low grade, except in influenza);

- Cough;

- Rhinitis or rhinorrhea;

- Diarrhea;

- Conjunctivitis;

- Discrete ulcerative stomatitis (painful, red, and swollen mucosa with open ulcers); or

- Viral exanthem (skin rash; CDC, 2018c; Chow & Doron, 2020; Luo, 2019).

There are some characteristic signs and symptoms that may help identify a particular viral cause for pharyngitis. Adenovirus tends to cause benign follicular conjunctivitis, fever, pharyngitis, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Coxsackie A viruses are most often seen in infants and young children, with incidence rates decreasing with age. This virus typically presents with vesicles in the posterior pharynx and/or on the soles of the feet and the palms of the hands. Pharyngeal edema occurs in approximately half of all children diagnosed with COVID-19, or SARS-CoV-2. The stomatitis caused by herpes simplex typically occurs in the anterior buccal mucosa but may extend to the tonsillar pillars (Fleisher, 2020). However, vesicles could be present within the mouth, lips, or throat. The blisters and pain may last several days to a few weeks, and the vesicles make it difficult for the patient to eat or drink. Lymph nodes may be swollen and tender (CDC, 2015). Mononucleosis is most often seen in adolescent patients and may present with significant tonsillar hypertrophy; this has the potential to cause respiratory distress and should be monitored closely due to the risk of airway obstruction. Symptoms typically develop gradually over days or weeks (Fleisher, 2020). Additional symptoms with mononucleosis (mono) include splenomegaly, extreme fatigue that may last more than a month, large and mildly tender posterior cervical lymph nodes, headache, and body aches. Symptoms may take four to six weeks to appear, during which time the patient may be contagious, and symptoms may persist for up to four months (Auwaerter, 2019; Fleisher, 2020; Johns Hopkins, n.d.). Influenza typically causes a fever, and may also cause headache, muscle/body aches, and fatigue (Dolin, 2018). Symptoms of an early HIV infection may also include headache and muscle and joint pain lasting approximately two weeks (Sax, 2019).

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis will be dependent on associated symptoms due to the existence of various pot

...purchase below to continue the course

If concern exists for a retropharyngeal abscess, as evidenced by significant difficulty swallowing or refusal to move the neck in an ill-appearing patient, a soft tissue radiograph of the lateral neck may prove helpful. This should be done in full extension during inspiration as a true lateral. A retropharyngeal abscess will typically result in a prevertebral space that is greater than half the thickness of the anteroposterior (AP) measurement of the adjacent vertebral body from C1-4, or 7 mm at C2, or greater than the full thickness of the vertebral body from C5-7 and 14 mm at C6 (Fleisher, 2020).

Treatment

Viral pharyngitis typically lasts five to seven days and is treated supportively. Antibiotics are neither effective nor recommended. The following are suggested for decreasing throat pain in all types of viral pharyngitis:

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol) or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as ibuprofen (Motrin) can reduce fever and pain.

- Oral rinses with salt-water (1 cup water with ¼ to ½ teaspoon of table salt).

- Oral anesthetic sprays such as phenol (Chloraseptic).

- Lozenges (cough drops) containing topical anesthetics such as benzocaine/menthol (Cepacol, Chloraseptic).

- Sipping honey/lemon tea, chicken soup, or other warm beverages, cold beverages, or frozen desserts such as ice cream or popsicles (children under one 12 months should not be given honey due to the risk of botulism poisoning) (Stead, 2019).

- Alternative therapies include chamomile tea, peppermint, fenugreek, marshmallow root, licorice root, slippery elm, apple cider vinegar, garlic, or cayenne pepper (Story & Gotter, 2017).

- Humidifying the ambient air through a humidifier or spending a few minutes in a closed bathroom with a hot shower several times a day may relieve throat pain.

- Avoiding exposure to tobacco smoke (Stead, 2019).

In severe cases of throat pain associated with difficulty swallowing, a short course of corticosteroids may be justified. Patient education regarding their options for pain relief, reassurance, and information about their illness was considered a higher priority for 80% of patients in a recent observational study. Only 38% of respondents indicated that they were hoping specifically for an antibiotic prescription (Stead, 2020). It is vital to ensure that patients and family members understand how to avoid further spread of infection. Individuals infected with a viral illness should practice good handwashing and avoid sharing utensils, drinks, or kissing. Follow-up for any of these illnesses is dependent on unresolved symptoms interfering with activities of daily living (Mayo Clinic, 2018).

Mono

The treatment goal for mono is to ease the impact of symptoms and allow the immune system to contain the virus. Antiviral therapy is not proven to treat or cure EBV effectively. In addition to the above supportive treatments for odynophagia, mononucleosis should be treated with the following:

- Rest is vital for patients with mono due to fatigue.

- Due to a loss of appetite, the diet may need to be modified.

- Increase fluids, particularly if taking ibuprofen (Motrin) for pain, to avoid dehydration as kidney damage can occur with extended use of NSAIDs (Auwaerter, 2019; Story & Gotter, 2017).

In severe cases, systemic oral corticosteroids may be indicated for concerns regarding excessive swelling in the throat or tonsils (Johns Hopkins, n.d.). Additionally, patients diagnosed with mono should be encouraged to continue to rest until fully recovered. Returning to their former level of activity may take several weeks to months. The patient should also avoid activities that could lead to injury due to the risk of splenic rupture, a medical emergency resulting in severe bleeding. Teens with mono not able to participate in school, activities, and sports may have difficulty with the isolation. Consider any psychological referrals for depression or anxiety as needed (Mayo Clinic, 2018).

Flu

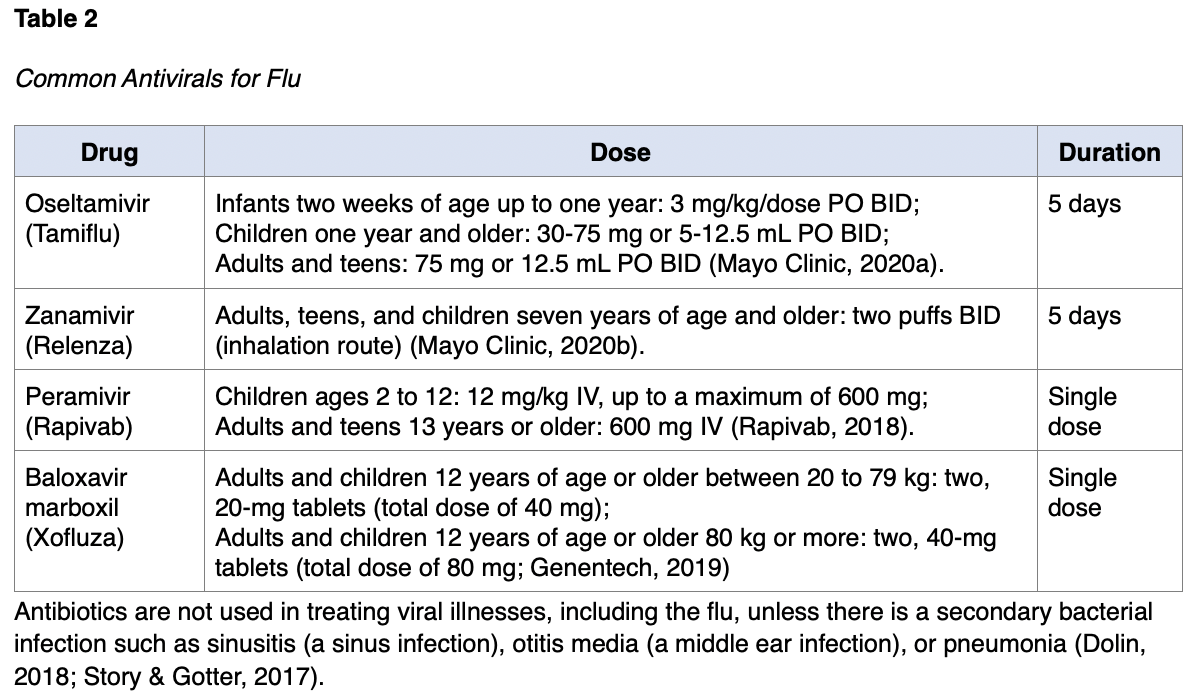

Flu is primarily treated symptomatically, but antiviral treatment may be used to reduce the severity and/or duration of symptoms. The decision to use antivirals should be based on how ill the patient is and/or the presence of risk factors for developing complications such as those over 65 years of age, young children under age four, those with a weakened immune system, diabetics, or those with a history of heart or lung disease. Individuals with no risk factors or who are only mildly ill should only be given antivirals if they have had symptoms for less than 48 hours after a discussion regarding the risks and benefits (Dolin, 2018). The CDC (2020a) notes that priority for antivirals should be given to anyone with suspected or confirmed flu that is hospitalized; has severe, complicated, or progressive illness; or those at high risk due to complications, as listed above. For common antivirals used with flu, see Table 2.

HIV

The patient diagnosed with HIV will have long term complex health maintenance concerns. Life-long antiretroviral therapy should be started immediately upon diagnosis to decrease the risk of transmitting HIV to others and to decrease the complications of infection for the individual. For sore throats related to HIV infection, the patient should use symptomatic treatments as listed above (Sax, 2019; Story & Gotter, 2017). For additional information regarding the management of chronic HIV/AIDs, please see the NursingCE course: HIV/AIDs.

Oral Herpes Simplex

Oral herpes treatment may include a topical anesthetic such as viscous lidocaine (Xylocaine), and PO antiviral medications such as acyclovir (Zovirax), valacyclovir (Valtrex), and famciclovir (Famvir). Initial outbreaks are typically treated for 7-10 days. Acyclovir (Zovirax) should be dosed at 400 mg three times daily (TID) or 200 mg five times daily. Valacyclovir (Valtrex) is typically dosed at 1 g twice daily and famciclovir (Famvir) at 250 mg TID. Dosage of PO antiviral medications may vary depending on the patient’s HIV status, age, and presence of underlying renal dysfunction. They can be nephrotoxic, and a dose reduction may be needed with acute or chronic kidney dysfunction. Patients should be educated that after discontinuing the medications, they do not eradicate the virus or reduce the risk, frequency, and severity of recurrences. Suppressive therapy can reduce outbreak frequency by 70-80%. Safety has been established for the use of acyclovir (Zovirax) for as long as six years and valacyclovir (Valtrex) and famciclovir (Famvir) for up to one year. Acyclovir (Zovirax) should be dosed at 400 mg BID for long-term suppression. Valacyclovir (Valtrex) can be dosed at 500 mg or 1 g daily and famciclovir (Famvir) at 250 mg BID. Valacyclovir (Valtrex) 500 mg daily has been shown to reduce sexual transmission. Famciclovir (Famvir) may be less effective than the other regimens for suppression of viral shedding. Episodic treatment can be effective at reducing the severity and duration of outbreaks if initiated within 24 hours of lesion onset. Acyclovir (Zovirax) should be dosed at 400 mg TID or 800 mg BID for five days or 800 mg TID for two days. Valacyclovir (Valtrex) can be dosed at 500 mg BID for three days or 1 g daily for five days. Famciclovir (Famvir) can be dosed at 125 mg BID for five days, 1 g BID for one day, or 500 mg once followed by 250 BID for two days. Topical therapies offer minimal clinical benefit and are not encouraged. Herpes is incurable and subject to lifelong periods of exacerbation/flare-ups and a need for treatment; some patients are on prophylactic antivirals (CDC, 2015).

Complications

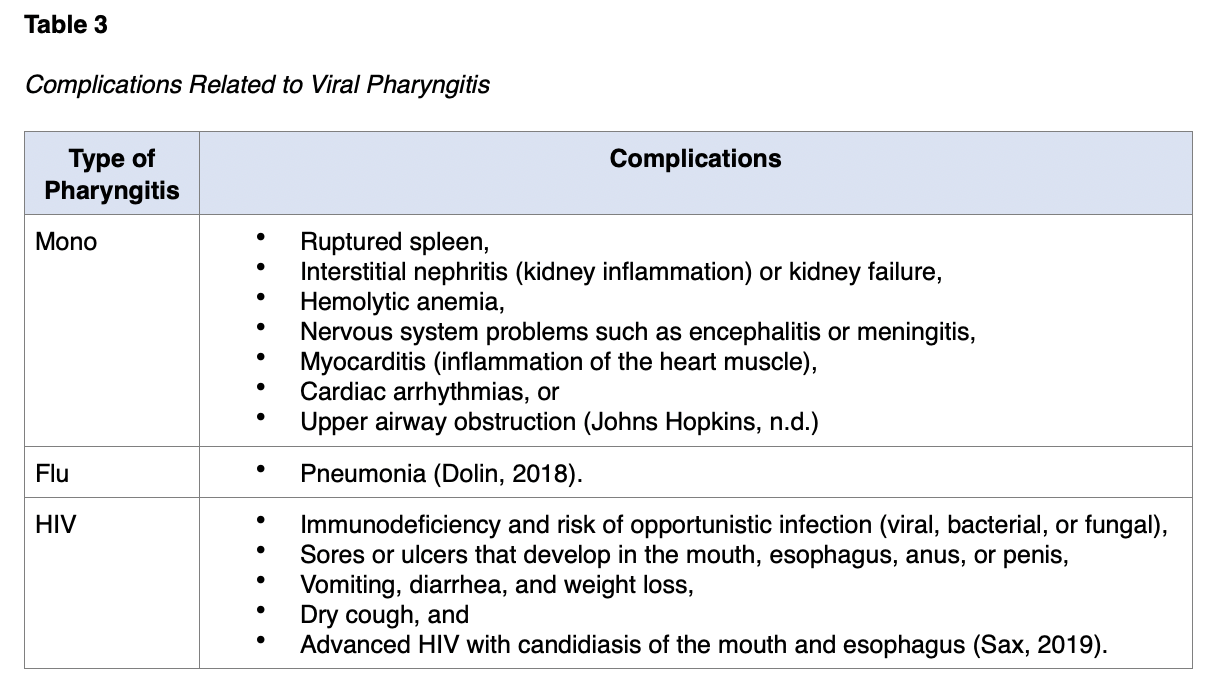

Viral pharyngitis may have disease-specific complications and implications, making follow-up vital to the avoidance or early identification of complications. See Table 3 for specific complications associated with these infections.

Group A Strep

Pathophysiology and Risk Factors

S. pyogenes are gram-positive cocci that grow in chains and belong to group A in the Lancefield classification system. For a GAS infection to develop, exposure through saliva or nasal secretions from an infected individual through person-to-person contact must occur. Those with acute, symptomatic infection are more likely than asymptomatic carriers to transmit the disease to others. In rare occurrences, exposure to the bacteria can result from contaminated food, particularly milk or milk products. Rarely, infections can be transmitted via food handling, or fomites via toys or shared kitchen items (i.e., plates, glasses, or utensils). Humans appear to be the primary source of the infection, and pets are not considered potential reservoirs that transmit the bacteria to humans. Following exposure, the bacteria adhere to the pharyngeal mucosa through adhesions on the surface of the organism and invade the mucosal tissue. They produce proteases and cytolysins that cause inflammation, manifesting as the signs and symptoms of pharyngitis. An M protein on the surface of the bacteria plays a role in the development of rheumatic fever and other complications from a GAS infection discussed later in this section (CDC, 2018c; Gibson, 2020). In addition to the risk factors listed above related to viral pharyngitis, close quarters promote infection, such as environments like schools, daycare centers, or military training facilities (CDC, 2018c).

Signs and Symptoms

The incubation period for GAS is two to five days. GAS infections most commonly present in children and adults as acute pharyngitis accompanied by the sudden onset of fever, tonsillar inflammation, odynophagia, and enlargement of the cervical lymph nodes. Less common symptoms may include a headache, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain. Close examination of the throat may show tonsillar erythema with or without exudate (see Figure 2), strawberry tongue, and petechiae along the palate. Children under three years of age with GAS infection rarely present with acute pharyngitis, but instead typically develop mucopurulent rhinitis (inflammation or swelling of the mucous membranes of the nose, causing the production of mucous and pus). These children may also present with high fever, anorexia (appetite loss), and irritability, known as streptococcal fever or streptococcus. These symptoms should be carefully delineated from the common presentation seen in viral pharyngitis, which is often accompanied by cough, rhinorrhea, hoarseness, and conjunctivitis (CDC, 2018c).

A scarlatiniform rash (see Figure 3) could be present and indicates a syndrome known as scarlet fever or scarlatina. The rash is typically erythematous, blanches when pressure is applied and has a characteristic sandpaper feel. It typically starts on the trunk and then spreads to the extremities, but is not commonly found on the face, palms, or soles. It may be accentuated in the flexor creases (groin, underarm, inside the elbow, behind the knee) and described as Pastia’s lines. The rash typically lasts for one week and may be followed by desquamation. The face may appear flushed, and a white/yellow coating with red papillae may develop on the tongue, followed by “strawberry tongue” (CDC, 2018e).

Diagnosis and Treatment

An accurate diagnosis made by symptoms alone is challenging since viral and bacterial pharyngitis present similarly (CDC, 2018c). Since most pharyngitis cases are due to GAS or a virus, initial screening should be focused on these two primary etiologies. The Centor criteria to identify patients at risk for GAS assigns one point for each of the following criteria:

- Fever greater than 100.5o F,

- Absence of cough,

- Tonsillar exudate,

- Tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy (Ferri, 2017).

If the patient is between 3 and 14 years of age, one point is added; if the patient is an adult greater than 45 years of age, one point is subtracted. Patients with one or less of the four criteria listed above are low risk and should not have additional testing. Patients with a score of 3 or above should be tested for GAS, although some will test with a score of 2. These criteria should not be used as a replacement for testing, but as a decision-making tool regarding which patients should be tested, and they are endorsed by the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, but not by the Infectious Disease Society of America (Chow & Doron, 2020; Ferri, 2017). Current US guidelines for GAS include a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) and a bacterial culture using a pharyngeal swab. RADTs are easy to use and have a turnaround time of fewer than 10 minutes. These tests have an 88-99% specificity, but a sensitivity of only 70 to 90%, increasing the risk of false negatives. Due to the low sensitivity, a negative RADT requires a bacterial culture in specific patient populations for confirmation. Cultures have a sensitivity between 90-95% and specificity between 95-99%. This is recommended for pediatric patients over three years of age (unless they have a sibling with known GAS pharyngitis), symptomatic household members of patients with GAS pharyngitis, or those at increased risk of complications. Cultures typically take 24-48 hours to return, and empirical treatment while awaiting culture results is unnecessary, as short delays in treatment are not associated with an increased risk for complications. Positive RADTs do not require a follow-up culture due to the high specificity of the test (Chow & Doron, 2020; Luo, 2019; Shulman, 2012).

Several NAAT assays for GAS pharyngitis diagnosis have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since 2016. NAAT assays provide sensitivity and specificity similar to bacterial culture and higher sensitivity than RADTs. This improved diagnosis with a single assay has led many healthcare facilities to implement this type of testing. With expedited transport and reporting, results can be obtained in hours. The rapid result and higher accuracy allow providers to decide on antibiotic use faster. The most recent GAS guidelines released in 2014 by Shulman and colleagues do not include the use of NAAT. However, the American Academy of Microbiology has suggested that practice guidelines should encourage their use as the NAAT perform as consistently as the gold standard bacterial culture (Dolen et al., 2017; Luo, 2019). Due to the very low risk of acute rheumatic fever (ARF), the CDC recommends that children younger than three years of age and adults should be tested routinely (CDC, 2018c).

Treatment of GAS is a priority due to potential complications, including ARF, rheumatic heart disease, or post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN). Treatment within nine days of the onset of symptoms has been shown to prevent ARF (Luo, 2019). The CDC (2018c) recommends antibiotic treatment for GAS pharyngitis to shorten the duration of the symptoms, prevent complications, and decrease the risk of transmission to others. The treatments of choice are penicillin (PCN, Pen-V) or amoxicillin (Amoxil). There are no confirmed reports of resistance to these antibiotics. For patients with a PCN allergy, a narrow-spectrum cephalosporin such as cephalexin (Keflex) or azithromycin (Zithromax) is recommended. Azithromycin (Zithromax) and clarithromycin (Biaxin) should not be utilized as first-line treatment for GAS pharyngitis, as there have been reports of resistance against these in some communities. See Table 4 for suggested antibiotic treatment regimens for GAS pharyngitis.

Adjunctive therapy with analgesics or antipyretics such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) or ibuprofen (Motrin) should be used for fever associated with GAS pharyngitis. Acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin) should be avoided in children with GAS pharyngitis due to the risk of Reye syndrome. Increased fluids and a diet as tolerated should be encouraged (CDC, 2018c). Routine follow-up RADT or cultures are not recommended except in special circumstances such as an unresolved infection (Shulman et al., 2012).

APRNs should ensure that children and adults diagnosed with GAS pharyngitis are educated on infection control measures. They should remain home from school, work, or daycare until they are afebrile and have been on antibiotic therapy for at least 24 hours. Optimal methods for infection prevention include proper handwashing and respiratory etiquette. Handwashing should occur after a cough or sneeze and before eating or preparing foods. The use of alcohol-based hand rubs is an equal alternative to handwashing if soap and water are not available (Wald, 2019b). Respiratory etiquette includes covering the mouth or nose during sneezes and coughs or coughing into the elbow. Droplet precautions should be implemented in hospitalized patients with GAS pharyngitis. Ensure the patient and caregiver understand their medication regime and the importance of taking all antibiotics as prescribed to avoid complications (CDC, 2018c). The APRN should educate caregivers about symptoms to monitor for that require immediate intervention as they may indicate upper airway obstruction or worsening infection, including the following:

- Difficulty swallowing or breathing (stridor, tachypnea, dyspnea, retractions);

- Excessive drooling in an infant or young child;

- Temperature higher than 101o F;

- Swelling or stiffness of the neck;

- Muffled, “hot potato” voice or hoarseness;

- “Sniffing” or tripod positioning to help maintain airway patency

- Difficulty opening their mouth (Chow & Doron, 2020; Wald, 2019b).

Complications

As previously mentioned, recurrent GAS infections may be an indication for tonsillectomy in children. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) reports that children with recurrent throat infections who undergo a tonsillectomy show a reduction in infections and a decrease in missed school days during the first year. Unfortunately, the benefits are not consistent after this initial timeframe. Parents must consider the potential harms of a tonsillectomy, including the risks of anesthesia and postoperative bleeding, combined with the prolonged throat pain and financial costs. Other possible intraoperative complications include damage to the teeth, pharyngeal wall, or soft palate; laryngospasm; aspiration; respiratory compromise; and cardiac arrest. Postoperative complications include nausea, vomiting, dehydration, and post-obstructive pulmonary edema (Mitchell et al., 2019).

Most cases of GAS pharyngitis resolve quickly with antibiotic therapy, but there are rare complications that can result in severe morbidities, such as suppurative (inflammation accompanied with pus formation or discharge) local infections (i.e., peritonsillar abscess, cervical lymphadenitis, mastoiditis) or nonsuppurative sequelae (i.e., ARF or PSGN; CDC, 2018c).

According to the American Association of Family Physicians, peritonsillar abscess typically presents with the aforementioned signs/symptoms of acute pharyngitis, in combination with dysphagia (which may present as drooling), trismus (lockjaw), and a muffled or “hot potato” voice. Patients may also report ear pain on the ipsilateral side, and the swelling may cause contralateral deviation of the uvula. Inspection of the pharynx reveals swelling and erythema unilaterally in the anterior tonsillar pillar and the overlying soft palate. It is most common in patients between the ages of 20 and 40. There is consensus that treatment should consist of drainage of the abscess with needle aspiration, followed by antibiotic therapy and symptomatic management of pain and/or fever if applicable (Galioto, 2017). Referral to an otolaryngologist should occur if peritonsillar or another abscess is suspected or if tonsillar hypertrophy persists (Ferri, 2017). Most can be managed as an outpatient, but hospitalization should be considered if symptoms do not improve within four hours of needle drainage. The preferred oral antibiotic regimen for adults is penicillin V (PCN, Pen-V) 500 mg PO every six hours plus metronidazole (Flagyl) 500 mg PO every six hours for 10-14 days. Alternative oral regimens include amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) 875 mg PO every 12 hours, a third-generation cephalosporin (cefdinir [Omnicef] 300 mg PO every 12 hours) plus metronidazole (Flagyl) 500 mg PO every six hours, or clindamycin (Cleocin) 300-450 mg PO every eight hours for 10-14 days. For hospitalized patients, the preferred regimen is intravenous penicillin G combined with metronidazole (Flagyl) 500 mg every six hours. Alternatives include ampicillin/sulbactam (Unasyn), ceftriaxone (Rocephin) combined with metronidazole (Flagyl), piperacillin/tazobactam (Zosyn), or clindamycin (Cleocin) if allergic to penicillin (Galioto, 2017).

Cervical lymphadenitis is the presence of enlarged, inflamed, and tender lymph nodes within the neck. This is to be differentiated from lymphadenopathy, which is the presence of enlarged lymph nodes. In patients with GAS infection, this typically presents with acute bilateral lymphadenitis that is accompanied by exudative pharyngitis, although some may present with unilateral findings. Differential diagnoses include Arcanobacterium hemolyticum and Epstein-Barr virus, especially in adolescents. The lymph nodes should gradually diminish in size and tenderness with appropriate antibiotic treatment for the underlying GAS infection, and follow-up may be scheduled for two to three weeks later to confirm resolution (Healy, 2018).

Although more commonly associated with acute otitis media, mastoiditis is a suppurative infection of the mastoid air cells. It is typically diagnosed clinically based on the presence of postauricular tenderness, erythema, swelling with protrusion of the auricle, and fever. Patients will report ear pain and lethargy/malaise. Due to its proximity to the facial nerve, semicircular canals, sternocleidomastoid muscle, jugular vein, internal carotid artery, sigmoid sinus, brain, and meninges, this condition carries a high level of risk for potentially serious complications (Wald, 2018). These patients should be referred to an otolaryngologist early. Treatment typically consists of aspiration and drainage of the mastoid and middle ear (myringotomy) and intravenous antibiotics. Complications may require additional surgical intervention, including a mastoidectomy (Wald, 2019a).

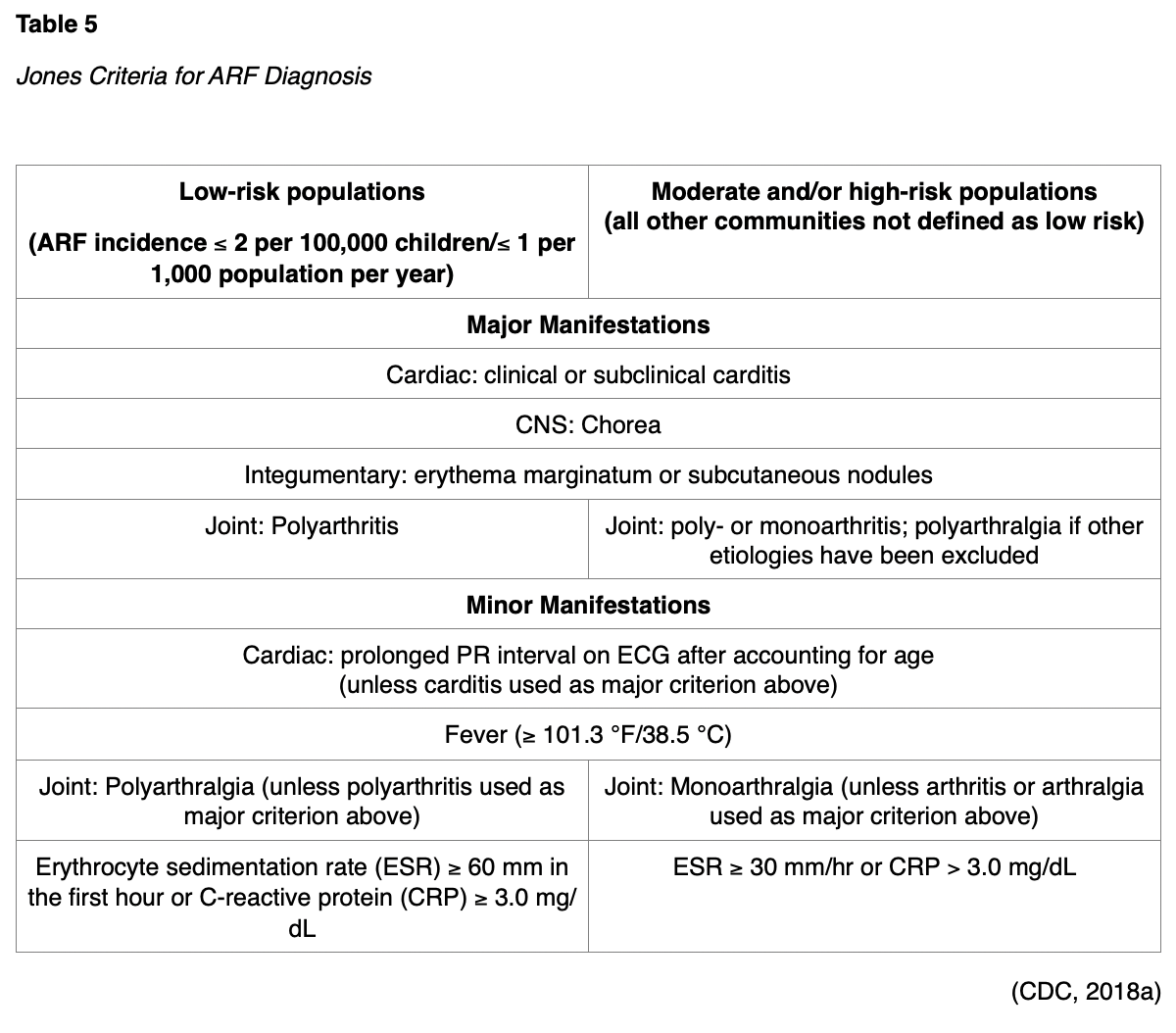

The immune response to GAS pharyngitis, rather than a direct result of the infection itself, is thought to be primarily responsible for ARF and PSGN (CDC, 2018c). Acute rheumatic fever is a delayed sequela of GAS pharyngitis that may affect the heart, joints, or nervous system. It typically presents one to five weeks after the onset of pharyngitis. The primary clinical feature is a fever. Most patients (50-70%) also present with carditis with or without valvulitis. Physical indications of carditis at presentation are typically a new-onset heart murmur, cardiomegaly, pericardial friction rub, pericardial effusion, or congestive heart failure. An electrocardiogram may indicate a prolonged PR interval. A migratory polyarthritis affecting the elbows, wrists, knees, and ankles may develop. Firm, painless subcutaneous nodules and erythema marginatum (non-pruritic, non-painful transient macular lesions typically found on the trunk or proximal extremities with outward extension and central clearing) may be evident. Chorea is the central nervous system manifestation most often found in those with ARF. Chorea is non-rhythmic, involuntary, sudden movements that are typically combined with emotional lability and muscle weakness. Inadequate antibiotic treatment for GAS pharyngitis increases the risk of ARF; approximately one-third of ARF cases follow a subclinical case of pharyngitis or one for which medical attention was not obtained. A prior history also increases the risk, especially for the first few years after the initial occurrence of ARF. Children between the ages of 5 and 15 years are at the highest risk, and ARF is extremely rare in the US in adults and children under the age of three. Differential diagnoses may include rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, septic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, serum sickness, Lyme disease, infective endocarditis, viral myocarditis, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, gout, sarcoidosis, leukemia, and Hodgkin’s disease. ARF is diagnosed clinically based on the Jones Criteria, in combination with evidence for previous GAS infection based on throat culture, rapid antigen test, or antibody titer. For the initial diagnosis of ARF, a patient must satisfy at least two major manifestations or one major and two minor manifestations. If one major manifestation is cardiac or joint-related, then the other manifestations must be from a separate clinical category. Recurrent ARF can be diagnosed based on the presence of three minor manifestations. See Table 5 below for Jones Criteria (CDC, 2018a).

Routine echocardiography/Doppler is recommended for patients with ARF, suspected or confirmed. Treatment consists of symptomatic management, including salicylates (aspirin, ASA) and anti-inflammatory medications to alleviate inflammation and correct fever as well as diuretics and antihypertensives. Antibiotic treatment should resume (as in Table 4) in order to eradicate any residual GAS regardless of whether or not pharyngitis is present. Long-term complications are typically related to rheumatic heart disease and vary based on the extent or severity of cardiac involvement (CDC, 2018a).

PSGN is caused by nephritogenic strains of GAS. It typically occurs 10 days after GAS pharyngitis or 21 days after a GAS skin infection, and clinical features of PSGN include:

- Facial or periorbital edema, particularly upon awakening;

- HTN;

- Proteinuria;

- Hematuria, with cola-colored urine (reddish-brown, dark);

- Lethargy, anorexia, and generalized weakness (CDC, 2018d).

Treatment for PSGN should include the management of any hypertension and/or edema. Antibiotics should be given as described above in Table 4, with a preference for Penicillin G benzathine (Bicillin L-A). While over 90% of children with PSGN will fully recover, some adults may develop long-term renal function impairment (CDC, 2018d).

Children are often reluctant to drink fluids due to odynophagia and are at risk for dehydration. Parents should be educated on monitoring for the signs of dehydration and encouraging fluid intake. Infants should produce at least one wet diaper every six hours. Early signs of dehydration include dry mouth, thirst, decreased urination, or darkening of the urine. Signs of moderate to severe dehydration include excessive thirst, a lack of tears when crying, sunken eyes and fontanels, irritability, listlessness, lightheadedness, tachycardia (rapid heart rate), low BP, and tachypnea (rapid breathing; Wedro, n.d.).

GAS pharyngitis in children may be associated with the development of autoimmune neuropsychiatric symptoms such as obsessive thoughts, compulsive behaviors (commonly seen in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder, or OCD), and tics (a habitual spasmodic contraction of the muscles); this is known as pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS). PANDAS typically present with an abrupt onset of the aforementioned symptoms associated with recent GAS infection. The condition is somewhat controversial as some children diagnosed with PANDAS have underlying comorbidities such as anxiety or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), making it difficult to differentiate between additional/worsening neuropsychiatric symptoms or an autoimmune response to GAS. Most cases of PANDAS resolve with antibiotic therapy. A tonsillectomy may decrease the number of GAS infections and reduce the symptoms of PANDAS (Demesh et al., 2015).

In addition to pharyngitis, GAS can also cause impetigo or invasive infections, including streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS), necrotizing fasciitis, bacteremia, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and pneumonia. STSS involves bacterial exotoxins within human tissues and the bloodstream inducing a cytokine cascade and leading to sudden shock and organ failure. The initial presentation for patients with STSS typically includes fever, chills, myalgia, nausea, and vomiting; this may progress quickly to hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, and signs/symptoms of organ failure suggestive of sepsis. Risk factors for STSS include age over 65 years, recent surgery, open wounds, or chronic illness such as alcohol use disorder or diabetes mellitus. It is typically diagnosed clinically based on the presence of hypotension (systolic blood pressure less than 90) and two or more indications of multi-organ involvement (i.e., renal impairment as evidenced by elevated creatinine, coagulopathy as evidenced by decreased platelet count, elevated liver enzymes, hypoxemia with acute diffuse pulmonary infiltrates, a generalized erythematous macular rash, or soft tissue necrosis); a positive culture for group A Streptococcus is typically used for confirmation. These patients require hospitalization with immediate fluid resuscitation and intravenous antibiotics, typically a combination of a penicillin (PCN) and clindamycin (Cleocin). Severe cases may also require surgical debridement and the use of intravenous immunoglobulin. The mortality rate for STSS is currently 30-70% (CDC, 2020d).

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) destroys the fascia and adipose tissue of the body. It typically occurs following trauma or surgery, or as a complication of a varicella lesion. NF most commonly affects the extremities, especially the legs. The presenting signs/symptoms include pain and warmth in the affected limb, along with swelling, erythema, and tenderness. The bulk of the tissue damage may not be readily apparent, as NF often spares the overlying skin. If untreated, the swelling can progress to brawny edema followed by dark red induration. The overlying skin may become dusky as cutaneous thrombosis and ischemia develop. Bullae, or fluid-filled sacs, may develop and become hemorrhagic. Tissue may appear progressively darker, from red towards black, if untreated. In severe cases, the skin may become anesthetized as superficial nerves are destroyed. Eventually, the skin will slough and necrotic eschar forms; this may appear similar to a third-degree burn. In an extremity, NF may lead to compartment syndrome, necessitating emergency fasciotomy. If left untreated, NF can continue to progress to sepsis, shock, organ failure, and death. Adults with compromised immune systems are at increased risk for NF, whether due to an immune disorder, medications, or chronic diseases such as diabetes. Treatment typically involves surgical debridement/exploration or biopsy for gram stain and culture. Incisions are typically large and should be left open for at least 24 hours for observation. Amputation may be required, depending on the location of the infection and the severity/extent of the tissue damage. Imaging studies in the form of computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful early but may also delay diagnosis and are not definitive. Patients typically present with abnormal laboratory findings, including leukocytosis (elevated white blood cell count), thrombocytopenia (decreased platelet count), and azotemia (elevated blood urea nitrogen). Broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics should be given initially, followed by high-dose penicillin (PCN) and clindamycin (Biaxin) once gram stain and culture results have identified S. pyogenes. Although not proven to be effective, intravenous immunoglobulin may be considered for severe cases. The mortality rate for NF is 24-34%. When coinciding with STSS (above), the mortality rate is 60% (CDC, 2018f).

Other Causes

Pathophysiology

Fungal pharyngitis (oropharyngeal candida infection or thrush) is common in breastfeeding infants and will cause significant pain. Otherwise, this is typically an opportunistic infection not seen in immunocompetent patients (CDC, 2020b). Haemophilus influenzae type B was once a common cause of febrile illness, especially in children. This typically presents with reports of pharyngitis, along with the typical symptoms of high fever, stridor, drooling, and an ill-appearing child. Epiglottitis is a concern as it could lead to life-threatening upper airway obstruction characterized by an abrupt onset. However, with the advent of routine vaccination against H. influenzae type b (Hib) in this country, the incidence has been dramatically reduced (Bush, 2020; Fleisher, 2020). Arcanobacterium haemolyticum, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, or other groups of streptococci (groups C or G) are among the bacteria that may cause acute pharyngitis. They are more commonly found in adolescent and young adult patients (Fleisher, 2020). A. haemolyticum only accounts for 1-2.5% of acute pharyngitis cases and is most common in adolescents or young adults (Chow & Doron, 2020). In addition to causing acute pharyngitis, Fusobacterium necrophorum infection can lead to Lemierre syndrome, a rare infection associated with jugular thrombophlebitis and the formation of septic emboli (Chow & Doron, 2020; Fleisher, 2020). Several less common sexually transmitted infections can cause pharyngitis, either independently or in conjunction with a comorbid infection. Oral Neisseria gonorrhea, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Treponema pallidum (the bacteria responsible for syphilis) are typically contracted sexually but can also cause oral infections presenting with pharyngitis following unprotected oral sexual contact with an infected individual (Fleisher, 2020).

Risk Factors

The risk factors for most of these infections include those listed in the viral pharyngitis section. The most significant risk factor for sexually transmitted infections is unprotected sexual activities (Sena & Cohen, 2020).

Signs and Symptoms

With most of the above organisms, the patient typically presents with symptoms similar to other viral infections, such as redness, irritation, odynophagia, and a cough (CDC, 2015). Oral candidiasis (fungal pharyngitis) typically presents with white patches along the buccal mucosa, tongue, soft palate, and pharynx with underlying erythema and tenderness. The patient may report a cotton sensation within the mouth and loss of taste. It is typically diagnosed clinically (CDC, 2020b). A. haemolyticum often presents similar to a GAS infection, with a scarlatiniform rash present in about half of cases. Pharyngitis related to M. pneumoniae or C. pneumoniae is typically associated with lower respiratory tract symptoms (Chow & Doron, 2020). F. necrophorum should be considered in very ill patients presenting with neck pain, severe pharyngitis, and respiratory distress (Chow & Doron, 2020; Fleisher, 2020). Oral chlamydia or gonorrhea can be asymptomatic or can cause acute pharyngitis and is associated with oral-genital contact (Sena & Cohen, 2020).

Diagnosis

History and physical exam may indicate the most likely causes for acute pharyngitis. History should inquire about recent travel, sick contacts, sexual exposure, recent immunizations, current medications, and any history of immunocompromising conditions. An inflamed eardrum likely indicates that the pathology is non-oropharyngeal and that the reports of throat pain are likely due to referred pain. Similarly, the presence of an inflamed area surrounding a tooth indicates potential abscess and warrants referral to a dentist (Fleisher, 2020). Supportive treatment should be attempted in acute pharyngitis patients if testing has ruled out GAS infection for at least five to seven days before additional diagnostic testing should be explored (Chow & Doron, 2020). Most other etiologies of acute pharyngitis can be diagnosed via throat culture. Note that while other strains of streptococci and A. haemolyticum can be diagnosed using a routine aerobic culture, F. necrophorum requires the use of an anaerobic culture. There are commercially available real-time PCR testing kits for M. pneumoniae and C. pneumoniae, which are much faster than culture or serology enzyme immunoassay; these tend to be expensive, they are not standardized, and there are currently only five FDA-approved assays in the US (CDC, 2020c). NAATs for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae are available but not FDA approved for use as oropharyngeal swabs; certain labs have been able to meet the regulatory requirements and established specifications for using these tests with oropharyngeal samples. These swabs are often done to detect both infections from a single specimen sample. The sensitivity of these NAAT tests for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae detection is superior to culture but varies by manufacturer. Diagnosis of infection with T. pallidum is confirmed via two separate tests: first, a nontreponemal test (i.e., Venereal Disease Research Lab [VDRL] or the Rapid Plasma Reagin [RPR]) followed by confirmation with a treponemal test (i.e., fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed [FTA-ABS], the passive particle agglutination [TP-TA] assay, an enzyme immunoassay [EIA], chemiluminescence immunoassay, immunoblot, or rapid treponemal assay; CDC, 2015; Sena & Cohen, 2020).

Treatment

Mild to moderate oral candidiasis is typically treated for 7-14 days with antifungal medications such as clotrimazole (Mycelex, 10 mg lozenge five times daily), miconazole (Oravig 50 mg buccal tab once daily), or nystatin (Nystop suspension, 100,000 U/mL, 4-6 mL four times daily or 200,000 U pastille four times daily). Severe cases should receive fluconazole (Diflucan) 100-200 mg daily for 7-14 days (CDC, 2020b). Pharyngitis related to mild H. influenzae infection can be treated with amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin), azithromycin (Zithromax), cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, or clarithromycin (Biaxin; Bush, 2020). Pharyngitis related to A. haemolyticum will typically resolve within two weeks without antibiotic treatment but may resolve within three days with treatment. Penicillin (PCN) or the macrolide erythromycin (E-Mycin) is generally accepted as the most effective. Many strains have developed resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) and/or tetracycline (Sumycin), so these should be avoided (Ufkes, 2017). Pharyngitis caused by M. pneumoniae or C. pneumoniae should not be treated with penicillin (PCN), as their lack of a cell wall makes them naturally resistant. Instead, treatment should consist of a macrolide (i.e., azithromycin [Zithromax]) in young children, a fluoroquinolone in adult patients, or a tetracycline (i.e., doxycycline [Vibramycin, Doryx]) in older children or adult patients if required (CDC, 2020c). Similar to GAS treatment as described above, penicillin (PCN) is the antibiotic of choice for the treatment of pharyngitis related to other streptococci groups (group C and G; Wessels, 2020). Macrolides should be avoided in pharyngitis related to anaerobes, such as F. necrophorum (Buensalido, 2019). In these cases, metronidazole (Flagyl) or clindamycin (Cleocin) should be used in combination with a beta-lactam (i.e., penicillin [PCN] or a cephalosporin; Arane & Goldman, 2016). Chlamydia treatment for oropharyngeal infections is similar to urogenital infections. The recommended regimen is azithromycin (Zithromax) 1 g PO in a single dose or doxycycline (Vibramycin, Doryx) 100 mg PO BID for seven days. Oropharyngeal gonorrhea infections are more difficult to eradicate than urogenital infections. The CDC recommended regimen includes a single dose of 250 mg ceftriaxone (Rocephin) IM and 1 g azithromycin (Zithromax) PO administered simultaneously and preferably under direct observation. Primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis should be treated in adults with penicillin G (Benzathine) 2.4 million units IM once (CDC, 2015; 2019).

The care of patients with any infectious disease should also include education related to the individual disease process and the potential to spread the disease to others. Symptomatic treatment for the associated sore throat is consistent with viral pharyngitis. Both mental and physical support is encouraged for patients suffering from these conditions, and referrals should be made as needed (Sena & Cohen, 2020).

Complications

The majority of these infections are self-limiting. As previously mentioned, H. influenzae pharyngitis can lead to epiglottitis with life-threatening airway obstruction. Gonorrhea or chlamydia can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease in women; epididymitis, leading to infertility in men; joint infections or arthritis; and pregnancy complications, such as miscarriage, premature birth, or transmission of the infection to the neonate during delivery (most newborns receive antibiotic ointment to their eyes due to the risk). Another potential complication of any sexually transmitted infection is the possibility of spread to sexual partners and other parts of the body (CDC, 2015; Sena & Cohen, 2020).

References

Arane, K. & Goldman, R. D. (2016). Fusobacterium infections in children. Can Fam Physician, 62(10); 813-14.

Auwaerter, P. G. (2019). Patient education Infectious mononucleosis (mono) In adults and adolescents (beyond the basics). [UpToDate]. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/infectious-mononucleosis-mono-in-adults-and-adolescents-beyond-the-basics#!

Badobadop. (2013). Scarlet fever. [image] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scarlet_Fever.jpg

Banerjee, S. & Ford, C. (2018). Clinical decision rules and strategies for the diagnosis of group A streptococcal infection: A review of clinical utility and guidelines. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532209/

Buensalido, J. A. (2019). Bacterial pharyngitis. https://www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/225243-overview

Bush, L. M. (2020). Haemophilus influenzae infections. https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/infections/bacterial-infections-gram-negative-bacteria/haemophilus-influenzae-infections

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). 2015 Sexually Transmitted Disease Treatment Guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018a). Acute rheumatic fever. https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/diseases-hcp/acute-rheumatic-fever.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018b). Epstein-Barr virus and infectious mononucleosis: Laboratory testing. https://www.cdc.gov/epstein-barr/laboratory-testing.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018c). Pharyngitis (strep throat). https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/diseases-hcp/strep-throat.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018d). Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis. https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/diseases-hcp/post-streptococcal.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018e). Scarlet Fever. https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/diseases-hcp/scarlet-fever.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018f). Type II necrotizing fasciitis. https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/diseases-hcp/necrotizing-fasciitis.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Gonorrhea treatment and care. https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/treatment.htm#:~:text=Gonorrhea%20Treatment%20and%20Care,-Antibiotics%20have%20successfully&text=Gonorrhea%20can%20be%20cured%20with,medication%20prescribed%20to%20cure%20gonorrhea

The Centers for Disease Control. (2020a). Influenza antiviral medications: Summary for clinicians. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm

The Centers for Disease Control. (2020b). Fungal infections. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/thrush/

The Centers for Disease Control. (2020c). Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. https://www.cdc.gov/pneumonia/atypical/mycoplasma/hcp/index.html

The Centers for Disease Control. (2020d). Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/diseases-hcp/Streptococcal-Toxic-Shock-Syndrome.html

Chow, A. W. & Doron, S. (2020). Evaluation of acute pharyngitis in adults. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-acute-pharyngitis-in-adults

Dake. (2006). Viral pharyngitis. [image]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pharyngitis.jpg

Demesh, D., Virbalas, J. M., & Bent, J. P. (2015). The role of tonsillectomy in the treatment of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS). JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, 141(3), 272-275. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2014.3407

Dolin, R. (2018). Patient education: Influenza symptoms and treatment (beyond the basics). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/influenza-symptoms-and-treatment-beyond-the-basics?topicRef=4013&source=see_link

Ferri, F. F. (2017). Ferri's clinical advisor 2917 E-Book. Elsevier.

Fleisher, G. R. (2020). Evaluation of sore throat in children. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-sore-throat-in-children

Galioto, N. J. (2017). Peritonsillar abscess. American Family Physician, 95(8), 501-506. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0415/p501.html

Genentech, Inc. (2019). Xofluza: Prescribing information. https://www.gene.com/download/pdf/xofluza_prescribing.pdf

Gibson, C.M. (2020). Strep throat pathophysiology. https://www.wikidoc.org/index.php/Strep_throat_pathophysiology

Harvard Health Publishing. (2020). Sore throat (pharyngitis): What is it? https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/sore-throat-pharyngitis-a-to-z#:~:text=The%20viruses%20that%20cause%20pharyngitis,sick%20person's%20nose%20or%20mouth

Healy, C. M. (2018). Cervical lymphadenitis in children: Diagnostic approach and initial management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/cervical-lymphadenitis-in-children-diagnostic-approach-and-initial-management

Johns Hopkins Medicine. (n.d.). Infectious mononucleosis. Retrieved on September 4, 2020, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/infectious-mononucleosis

Luo, R., Sickler, J., Vahidnia, F., Lee, Y., Frogner, B., & Thompson, M. (2019). Diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis in the United States, 2011-2015. BMC Infectious Diseases, 19(193), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3835-4

Mayo Clinic. (2017). Sore throat: Symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sore-throat/symptoms-causes/syc-20351635

Mayo Clinic. (2018). Mononucleosis. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/mononucleosis/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20350333

Mayo Clinic. (2020a). Oseltamivir (oral route). https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/oseltamivir-oral-route/proper-use/drg-20067586

Mayo Clinic. (2020b). Zanamivir (inhalation route). https://www.mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements/zanamivir-inhalation-route/proper-use/drg-20066752

Mitchell, R. B., Archer, S. M., Ishman, S. L., Rosenfeld, R. M., Coles, S., Finestone, S. A., Friedman, N. R., Giordano, T., Hildrew, D. M., Kim, T. W., Lloyd, R. M., Parikh, S. R., Shulman, S. T., Walner, D. L., Walsh, S. A. & Nnacheta, L. C. (2019). Clinical practice guideline: Tonsillectomy in children (update). Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 160(IS) S1-S42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599818801757

Optigan13. (2008). Streptococcal pharyngitis. [Image]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Streptococcal_pharyngitis_1.jpg

Rapivab. (2018). Dosing and administration. https://www.rapivab.com/dosing-and-administration

Sax, P. E. (2019). Patient education: Symptoms of HIV infection (beyond the basics). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/symptoms-of-hiv-infection-beyond-the-basics?topicRef=4013&source=see_link

Sax, P. E. (2020). Patient education: Testing for HIV (beyond the basics). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/testing-for-hiv-beyond-the-basics?topicRef=3695&source=see_link

Sena, A. C. & Cohen, M. S. (2020). Patient education: Gonorrhea (beyond the basics). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/gonorrhea-beyond-the-basics?topicRef=4013&source=see_link

Shulman, S. T., Bisno, A. L., Clegg, H. W., Gerber, M. A., Kaplan, E. L., Lee, G., Martin, J. M., & Van Beneden, C. (2012). Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012, update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 55(10), e86-e102. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cis629

Shulman, S. T., Bisno, A. L., Clegg, H. W., Gerber, M. A., Kaplan, E. L., Lee, G., Martin, J. M., & Van Beneden, C. (2014). Correction to clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 58(10), 1496. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu172

Stead, W. (2019). Patient education: Sore throat in adults (beyond the basics). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/sore-throat-in-adults-beyond-the-basics/print

Stead, W. (2020). Symptomatic treatment of acute pharyngitis in adults. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/symptomatic-treatment-of-acute-pharyngitis-in-adults

Story, C. M. & Gotter, A. (2017). 12 natural remedies for sore throat. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/cold-flu/sore-throat-natural-remedies

Ufkes, N. (2017). Arcanobacterium haemolyticum. https://www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/1054547-overview

Wald, E. R. (2018). Acute mastoiditis in children: Clinical features and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acute-mastoiditis-in-children-clinical-features-and-diagnosis

Wald, E. R. (2019a). Acute mastoiditis in children: Treatment and prevention. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acute-mastoiditis-in-children-treatment-and-prevention

Wald, E. R. (2019b). Patient education: Sore throat in children (beyond the basics). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/sore-throat-in-children-beyond-the-basics?topicRef=4013&source=see_link

Wedro, B. (n.d.). Dehydration. Retrieved on August 14, 2020, from https://www.medicinenet.com/dehydration/article.htm

Wessels, M. R. (2020). Group C and group G streptococcal infection. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/group-c-and-group-g-streptococcal-infection