About this course:

The purpose of this module is to review the most common blood clotting and bleeding disorders, examining the clinical manifestations and implications of each disease process, as well as the clinical considerations for prescribing therapy as a means to enhance clinical practice and improve patient outcomes.

Course preview

By the completion of this module, the APRN should be able to:

- Describe the pathophysiology of normal bleeding and blood clotting, discuss the distinction between primary and secondary hemostasis, as well as provide an overview of the clotting cascade and coagulation factors.

- Describe the pathologic mechanisms of blood clotting failure or impairment, delineating the most common domains of dysfunction.

- Discuss anticoagulation therapy, reviewing the most common classes of medications, their indications, monitoring parameters, and side effects.

- Review the most common disorders of excessive blood clotting, inheritance patterns, and their clinical manifestations, as well as the recommended treatments.

- Review the most common bleeding disorders, inheritance patterns, and their clinical manifestations, as well as the recommended treatments.

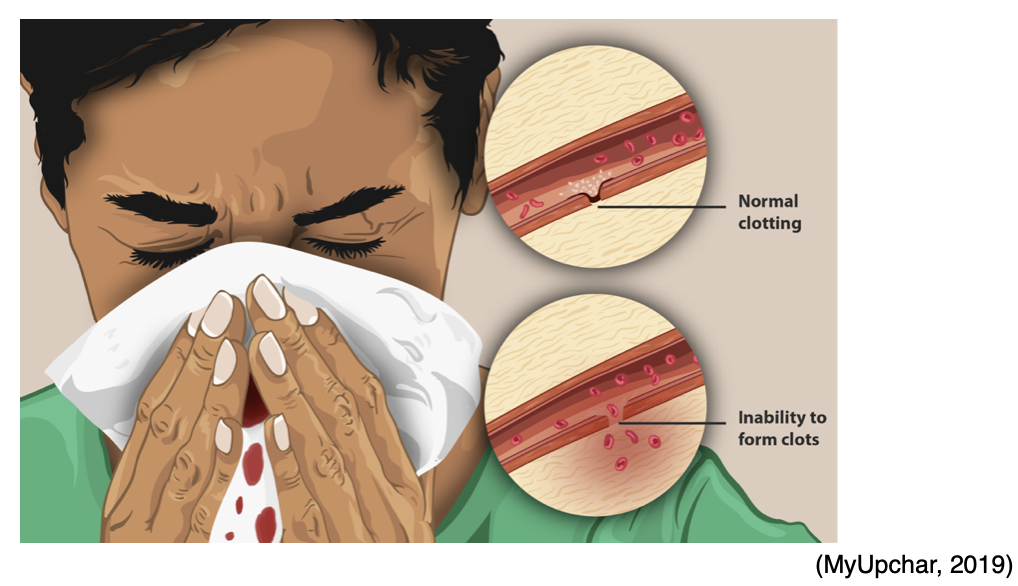

When the body's physiologic mechanisms of blood clotting fail, excessive blood clotting or excessive bleeding can ensue. Disorders of blood clotting occur when there is an imbalance between factors that promote blood clotting (procoagulants) and the factors that inhibit blood clotting (anticoagulants). Blood clotting disorders are characterized by an impairment in the ability to effectively form a blood clot (or thrombus) in response to an injury. They may also be due to a hypercoagulable state in which there is an increased tendency to develop thrombus' in the arteries and veins. These conditions can be inherited (congenital) due to specific genetic defects present at birth, or acquired (developed), resulting from an underlying medical condition, trauma, surgery, or medication. If not promptly identified and effectively treated, blood clotting disorders can lead to serious health consequences, including hemorrhage, heart attack, stroke, organ failure, and death. To understand blood clotting disorders, it is first essential to understand the physiologic basis of blood cell production, and the mechanisms of bleeding and blood clotting (Longo, 2019).

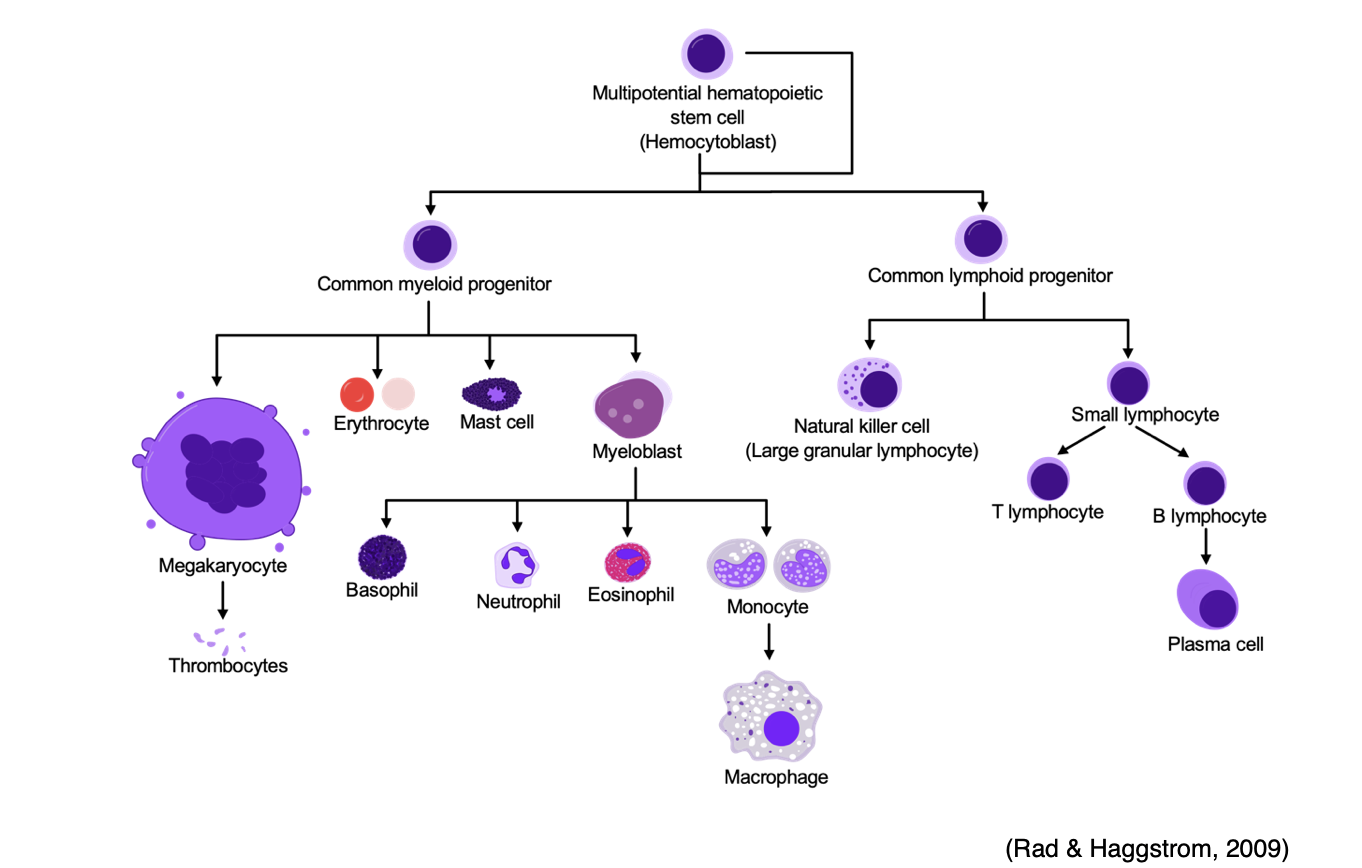

Hematopoiesis

Hematopoiesis is the ongoing process of blood cell production in the human body that primarily occurs in the bone marrow. The process is regulated through a series of steps in which undifferentiated cells are biochemically stimulated to undergo mitotic cell division (i.e., proliferation) and cell maturation (i.e., differentiation). Hematopoiesis continues throughout the lifespan, functioning to maintain homeostasis within the body in response to infection or injury (Longo, 2019). When there is an increase in the destruction of circulating cells, such as during an acute bleeding event, hematopoiesis accelerates to generate more cells and compensate for the loss. In long-term dysfunction, as in chronic illness, there is a more significant increase in hematopoiesis than in acute conditions such as hemorrhage. As demonstrated in Figure 1, every cell type in the body originates from hematopoietic stem cells. The stem cells grow, multiply, and differentiate under the control of cytokines and growth factors. During the differentiation process, the stem cells follow distinctive paths to maturity, and travel down committed lines of blood cells, primed to perform a specific function. The average human body requires nearly 100 billion new blood cells per day, which is why hematopoietic stem cells are self-renewing or can proliferate by themselves so that a relatively constant population of stem cells is always readily available (McClance & Heuther, 2019).

Figure 1

Hematopoiesis

Components of Blood

Blood is a vital component of the body. It serves several important functions, including transporting oxygen and nutrients to tissues within the body, regulating temperature, and responding to blood vessel injuries to maintain homeostasis. The amount of blood within each individual depends on their size, but the average adult has approximately 5 liters (1.3 gallons) of blood circulating within their body. Blood consists of both solid (formed) elements (white blood cells [WBCs], red blood cells [RBCs], and platelets), and liquid components (plasma) (Longo, 2019).

WBCs

WBCs are the components of the immune system which work to fight infection and other illnesses. WBCs are comprised of five specific subtypes (neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, eosinophils, and basophils). Each WBC serves a specific function in mediating the inflammatory and immune response to infection. WBCs have variable lifespans, as some may live for only 24 hours, but the average WBC lifespan is 13 to 20 days (Longo, 2019).

RBCs

RBCs are mature red blood cells (erythrocytes) and carry hemoglobin, a protein that transports oxygen from the lungs to all the tissues within the body. The body relies on oxygen as a critical component for all cellular functioning and processes. Hemoglobin also carries waste products (mainly carbon dioxide) from the tissues back to the lungs, where waste is expelled through breathing. Erythrocytes comprise about 45% of total blood, have an average lifespan of 120 days, and are pink in appearance due to their high hemoglobin content. Hematocrit reflects the percentage of RBCs in a given volume of blood (Longo, 2019).

Platelets

Platelets, also called thrombocytes, have a critical role with regards to all aspects of bleeding and clotting. They are produced in the bone marrow from cells called megakaryocytes. The process of platelet differentiation, as outlined in Figure 2, is regulated under the control of thrombopoietin (TPO), a hormone produced by the liver and kidneys. TPO influences the growth and differentiation of myeloid stem cells into megakaryoblasts, the precursor cell to the promegakaryocyte, which, in turn, develops into a giant megakaryocyte. As demonstrated earlier in Figure 1, megakaryocytes are depicted as notably larger than all the other cells because each megakaryocyte is prepared to produce and release more than 1,000 platelets, accounting for their large size. Platelets are colorless fragments of blood cells that are essential for blood clotting in response to an injury. They contain proteins on their surfaces that allow them to stick to each other and blood vessel walls. Their primary function is to gather at the site of the blood vessel injury to seal small cuts or breaks in blood vessels to control bleeding. They function in collaboration with proteins called clotting factors to stop bleeding and change shape in response to injury to ensure all injured parts of the vessel are sealed. Platelets have an average lifespan of 7 to 10 days, and a healthy adult platelet count is 150,000–450,000/microliter (μL). Thrombocytopenia is a condition where the platelet count is lower than normal, thereby heightening the risk for bleeding events and hemorrhage. Thrombocytosis occurs when there is an excessive number of platelets in the blood, increasing the risk of forming blood clots (Longo, 2019).

Figure 2

Platelet Development

Plasma

Plasma is an aqueous component of blood that functions to carry nutrients, proteins, and hormones throughout the body and transport waste products to the kidneys and digestive tract for removal. As demonstrated in Figure 3, plasma accounts for about 55% of whole blood volume and is comprised primarily of water (92%), with 8% of dissolved substances (solutes). Plasma proteins encompass about 7% of the total plasma volume and include albumin, immunoglobulins, and clotting factors. The liver produces the

...purchase below to continue the course

Figure 3

Components of Blood

Physiologic Mechanisms of Blood Clotting (Coagulation)

Blood clotting, commonly referred to as coagulation, is a vital mechanism that protects against blood loss due to bleeding. A complex interplay mediates the process between vascular mechanisms, enzymes, hormones, proteins, and cells. Hemostasis, or the cessation of bleeding, refers to the body's physiological response to stop bleeding from an injured blood vessel to prevent blood loss. The coagulation process is divided into two stages: primary hemostasis (which results in the formation of a weak platelet plug) and secondary hemostasis (which stabilizes the weak platelet plug, evolving into a secure and insoluble fibrin clot). The defining components of each process are as follows:

- Primary hemostasis:

- Vascular spasm or vasoconstriction of the blood vessel,

- Platelet adhesion,

- Platelets activation (or secretion),

- Platelet aggregation.

- Secondary hemostasis:

- Activation of clotting factors,

- Conversion of prothrombin to thrombin,

- Conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin (Garmo et al., 2020).

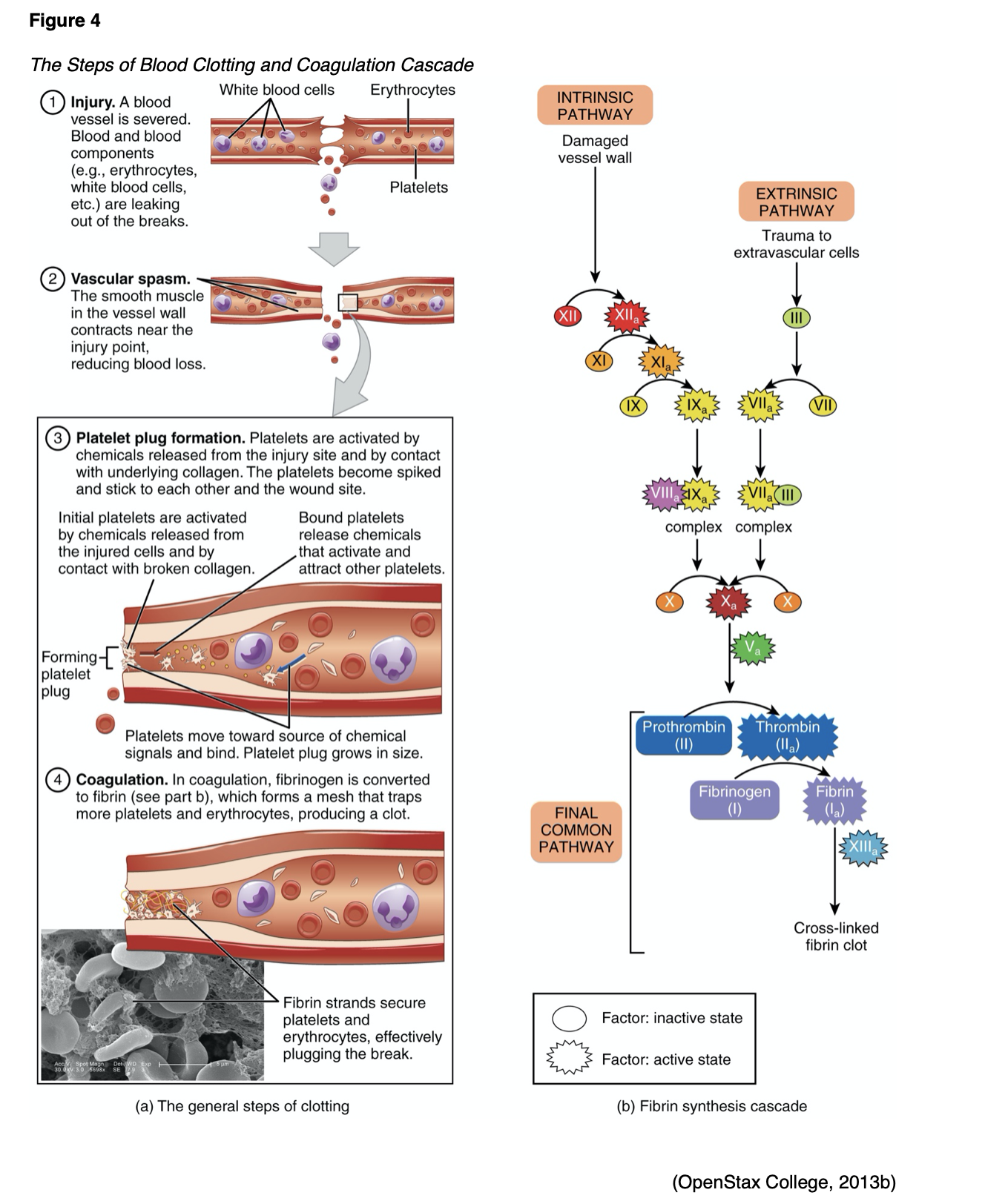

As outlined in Figure 4 (part a), upon recognition of an injury, the vessel constricts (tightens) to reduce blood flow to the area to prevent further blood loss. Vasoconstriction is mediated by endothelin-1, a potent vasoconstrictor, which is synthesized by the damaged endothelium. The damaged endothelium leaks collagen and proteins, including von Willebrand factor (vWF), into the bloodstream. vWF, a protein, is the primary mediating factor for platelet adhesion, acting like a glue and binding the platelets with enough strength to withstand stress and prevent detachment. Platelets circulating in the blood travel to the site of injury and adhere to the vessel walls, sticking together to form a temporary platelet plug. Platelets mainly bind to collagen in tissues at the site of vessel wall injury and exposed vWF at the damaged vessel site. When this happens, signals are sent into the bloodstream, calling more platelets to the site of injury; inducing platelet activation. Platelet aggregation begins once platelets have been activated. Calcium is released and attaches to the phospholipids (a main component of cellular membranes), which appear secondary to the platelet activation, offering a surface for various coagulation factors. Thromboxane A2, a potent vasoconstrictor, is formed during platelet activation; it functions as a stimulus for platelet aggregation and mediates the release of adenosine phosphate (ADP). ADP is a platelet agonist that activates other platelets, directing more platelets to the injury area. ADP enables platelets to clump together and change shape as a means to increase their surface area. Thrombin, formed during the coagulation cascade (which will be reviewed in the next section), is the most potent activator of platelets and is considered the key enzyme of coagulation. Fibrinogen, along with the platelets, creates a weak platelet plug that temporarily protects against further bleeding (Gross et al., 2018). Secondary hemostasis subsequently kicks in, and the clotting factors act to stabilize the platelet plug and convert it into a hard, insoluble fibrin clot (Garmo et al., 2020).

Clotting Factors

There are 12 clotting factors (F) labeled in roman numerals (FI through FXIII) as outlined in Table 1. Of note, there is no clotting FVI. Clotting factors are proteins that are primarily secreted by the platelets and liver and are dependent upon calcium ions (Ca2+), and vitamin K. Ca2+ are vital for the acceleration of blood clotting. Vitamin K is a naturally occurring fat-soluble vitamin synthesized by bacteria residing in the large intestine and is also consumed in the diet. Vitamin K assists with blood clotting, bone metabolism, regulation of blood calcium levels, and is required to produce prothrombin (FII). Therefore, vitamin K deficiencies can lead to bleeding and hemorrhage, bone mineralization, and osteoporosis. Ca2+, otherwise referred to as FIV, is derived from the breakdown of bone and is also acquired via the diet (McCance & Heuther, 2019).

Table 1

Clotting Factors

Factor | Common Name | Function |

FI | Fibrinogen | Helps control bleeding by assisting with fibrin clot formation |

FII | Prothrombin* | Assists FVIIIa, FIXa, and FVa in formation of thrombin |

FIII | Tissue Factor (TF) | Assists FVII and FIV in activation of FIX and FX |

FIV | Calcium Ions (Ca 2+) | Necessary for the activation of multiple clotting factors |

FV | Proaccelerin (Labile Factor) | Assists FVIIIa, FIxa, FXa and FII in formation of thrombin |

FVII | Proconvertin (Stable Factor)* | Assists TF and FIV in activation of FIX and FX |

FVIII | Antihemophilic Factor (AHF) | Activated by thrombin to amplify formation of additional thrombin |

FIX | Plasma Thromboplastin* Component (PTC) or Christmas Factor | Assists FVa, FVIIIa, FXa and II with formation of thrombin |

FX | Stuart-Prower Factor* (thrombokinase) | Assists FVIIIa, FIxa, FVa and II with formation of thrombin |

FXI | Plasma Thromboplastin Antecedent (PTA) or antihemophilic factor C | Activated by thrombin in extrinsic pathway to increase production of thrombin inside fibrin clot through the intrinsic pathway; helps slow down fibrinolysis |

FXII | Hageman Factor (contact factor) | Contact activator of the kinin system |

FXIII | Fibrin Stabilizing Factor (FSF) | Activated by thrombin and helps with formation of bonds between fibrin strands during secondary hemostasis |

*Vitamin K required. (Gross et al., 2018)

Coagulation Cascade

The coagulation cascade, as demonstrated in Figure 4 (part b), is activated through two distinct yet interconnected pathways (intrinsic and extrinsic) that converge into the common pathway, which lead to the formation of a fibrin clot. All three pathways are mediated by hormones, proteins, and clotting factors through a series of complex events. The ultimate goal of the coagulation cascade is to convert fibrinogen (F1), a soluble plasma protein into fibrin, a non-soluble plasma protein. The coagulation cascade can be summarized by the following three essential steps:

- Extrinsic and intrinsic pathways form the enzyme prothrombinase;

- Prothrombinase converts prothrombin to thrombin;

- Thrombin converts fibrinogen into fibrin (Gross et al., 2018).

Extrinsic pathway. Clotting factors involved in the extrinsic pathway include FVII and FIII. The beginning of the process towards fibrin clot formation is carried out by the extrinsic pathway, activated in response to external tissue trauma, in which blood escapes from the vascular system. Once the damage is identified, tissue factor (TF, or FIII), a cell membrane protein, is released from the damaged cells. TF binds with prothrombin (FVII), activating it into FVIIa, thereby initiating the clotting cascade. The extrinsic pathway is much quicker and less complex than the intrinsic pathway.

Intrinsic pathway. Clotting factors involved in this pathway include FXII, FXI, FIX, and FVIII. The intrinsic pathway is activated by trauma that begins inside the vascular system, prompted by internal damage to the vessel wall. FXII is activated into FXIIa when it comes in contact with the damaged endothelial collagen, thereby igniting the intrinsic pathway. This pathway is slower than the extrinsic pathway but is considered more important.

Common Pathway. Clotting factors involved in the common pathway include FX, FV, FII, FI, and FXIII. The extrinsic and intrinsic pathways converge into the common pathway with the activation of FX into FXa, which subsequently combines with FVa and Ca2+ on phospholipid surfaces. This process activates FII into thrombin, which then activates FXIIIa. FXIIIa interacts with fibrin to form the stabilized clot (Garmo et al., 2020; Gross et al., 2018).

Antithrombotic Mechanisms

Parallel to the coagulation cascade, the body also has an innate, highly regulated process for controlling and preventing abnormal blood clot development. Antithrombotic mechanisms are naturally occurring anticoagulants in the body. An anticoagulant refers to any substance that opposes coagulation. Coagulation is regulated by several antithrombotic mechanisms to preserve the fluidity of the blood and limit blood clotting to vascular injury sites, so blood clots do not form under normal conditions. The endothelial cells provide several antithrombotic effects. They produce substances that act to inhibit platelet binding, secretion, and aggregation, and generate anticoagulant factors such as tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) and antithrombin. Various circulating plasma anticoagulants instinctively function to limit the coagulation process to the area of injury and to reestablish and maintain patency of blood vessels. Endothelial cells also activate the fibrinolytic mechanisms through the production of tissue plasminogen activator 1 (tPA) and plasminogen activator inhibitor. Further, basophils of the immune system also play a fundamental role in preventing blood clotting through their release of heparin, a short-acting anticoagulant that opposes prothrombin. Heparin is additionally found on the surfaces of cells lining the blood vessels and promotes blood fluidity (Garmo et al., 2020; Gross et al., 2018). The major physiologic antithrombotic pathways and their impact on the coagulation cascade are illustrated in Figure 5 (highlighted in red) and described below.

Figure 5

Coagulation Cascade with Antithrombotic Mechanisms

Antithrombin (AT)

Previously referred to as antithrombin III, AT is the major inhibitor of thrombin and other clotting factors in the coagulation cascade. AT is activated by binding to heparin on endothelial cell surfaces. It binds to and inactivates FIXa, FXa, FXIa, and FXIIa, and opposes the conversion of prothrombin (FII) to thrombin in the common pathway. AT neutralizes thrombin and other activated clotting factors on the vascular surface (Longo, 2019).

Protein C and Protein S (Protein C/S)

Protein C/S refers to a cluster of plasma proteins that work together to regulate blood clot formation. Protein C inactivates clotting factors involved in the intrinsic pathway, serving as a natural anticoagulant when activated by thrombin. Thrombin-induced activated protein C (APC) occurs on thrombomodulin, a transmembrane binding site for thrombin on the endothelial cell surface. APC subsequently inactivates FVa and FVIIIa, slowing down blood clot formation. Protein S exists in two forms; free and bound to another protein. As demonstrated in Figure 5, free protein S is a cofactor to protein C, functioning to accelerate the inactivation of FVa and FVIIIa (Longo, 2019).

Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor (TFPI)

TFPI is generated primarily by endothelial cells and inhibits the TF/FVIIa/FXa complex, turning off the initiation of the coagulation cascade's extrinsic pathway. TFPI is bound to lipoprotein and can be released by heparin. It also circulates in plasma in a free form in small quantities, acting as a physiologically active anticoagulant (Longo, 2019).

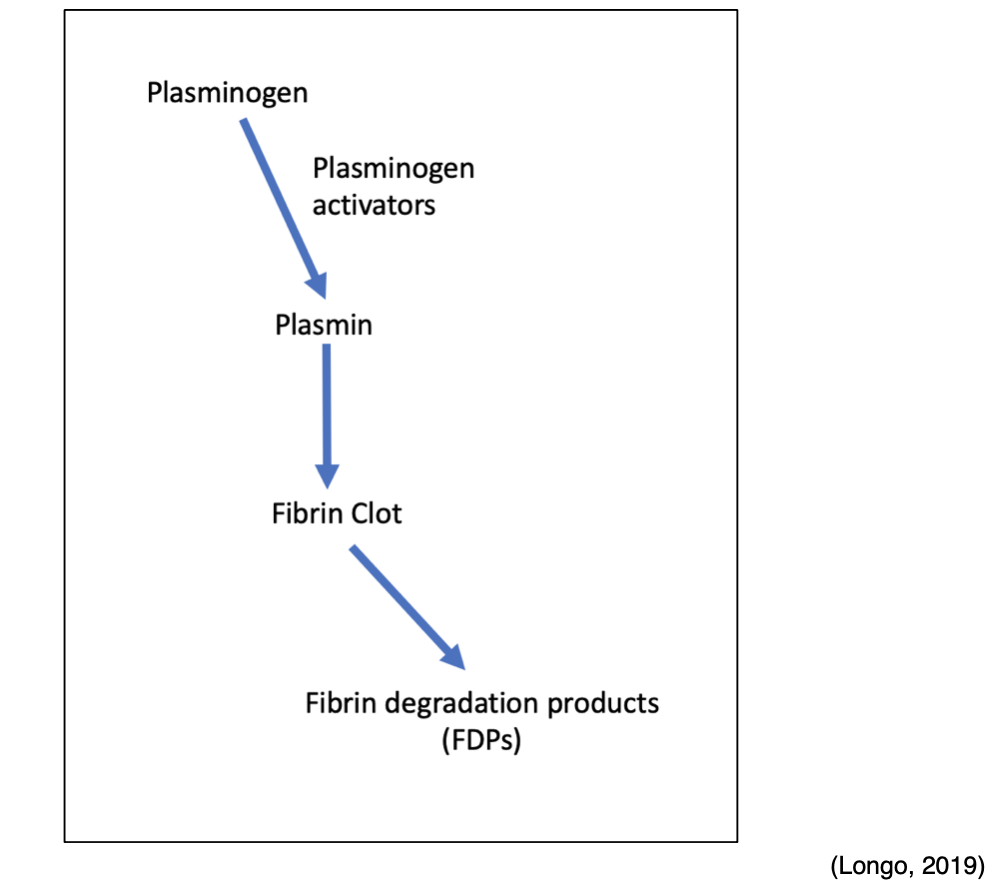

Fibrinolytic System

Any thrombin that evades the inhibitory effects of the body's natural anticoagulant system is used to convert fibrinogen to fibrin. However, once the injured blood vessel heals, the clot must eventually be removed to reestablish normal blood flow and maintain patency of the blood. Therefore, the fibrinolytic system and fibrinolysis process are activated to facilitate the breakdown and removal of these unwanted fibrin deposits. In addition to the degradation of fibrin, fibrinolysis also regulates the abnormal development of blood clots and manipulates the extent of blood clot formation. Plasmin is the primary enzyme of the fibrinolytic system, functioning to digest fibrin into fibrin degradation products (FDPs). Plasmin is formed through a series of reactions, as demonstrated in Figure 6. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is released from endothelial cells and binds to the fibrin clot. Subsequently, inactivated plasminogen (an enzyme that degrades fibrin clots) is converted into active plasmin. The process of fibrinolysis can be primary or secondary. Primary fibrinolysis is the body's natural process to maintain homeostasis, as described above. In contrast, secondary fibrinolysis refers to the dysfunctional breakdown of blood clots secondary to medical disorders, infections, or medications, and can induce severe bleeding (Garmo et al., 2020; Leung, 2020b; Longo, 2019).

Figure 6

Fibrinolytic System

Thrombosis

Thrombosis is a pathologic process in which there is an increased tendency to develop abnormal blood clots (thrombi) within uninjured blood vessels. A thrombus is a stationary clot attached to the vessel wall primarily composed of fibrin and other blood cells. As demonstrated in Figure 7, the thrombus can grow large enough to reduce or obstruct blood flow within the vessel, thereby depriving tissues and organs of vital nutrients, inducing tissue ischemia and hypoxia (Longo, 2019).

Figure 7

Blood Clot (Thrombus) Diagram

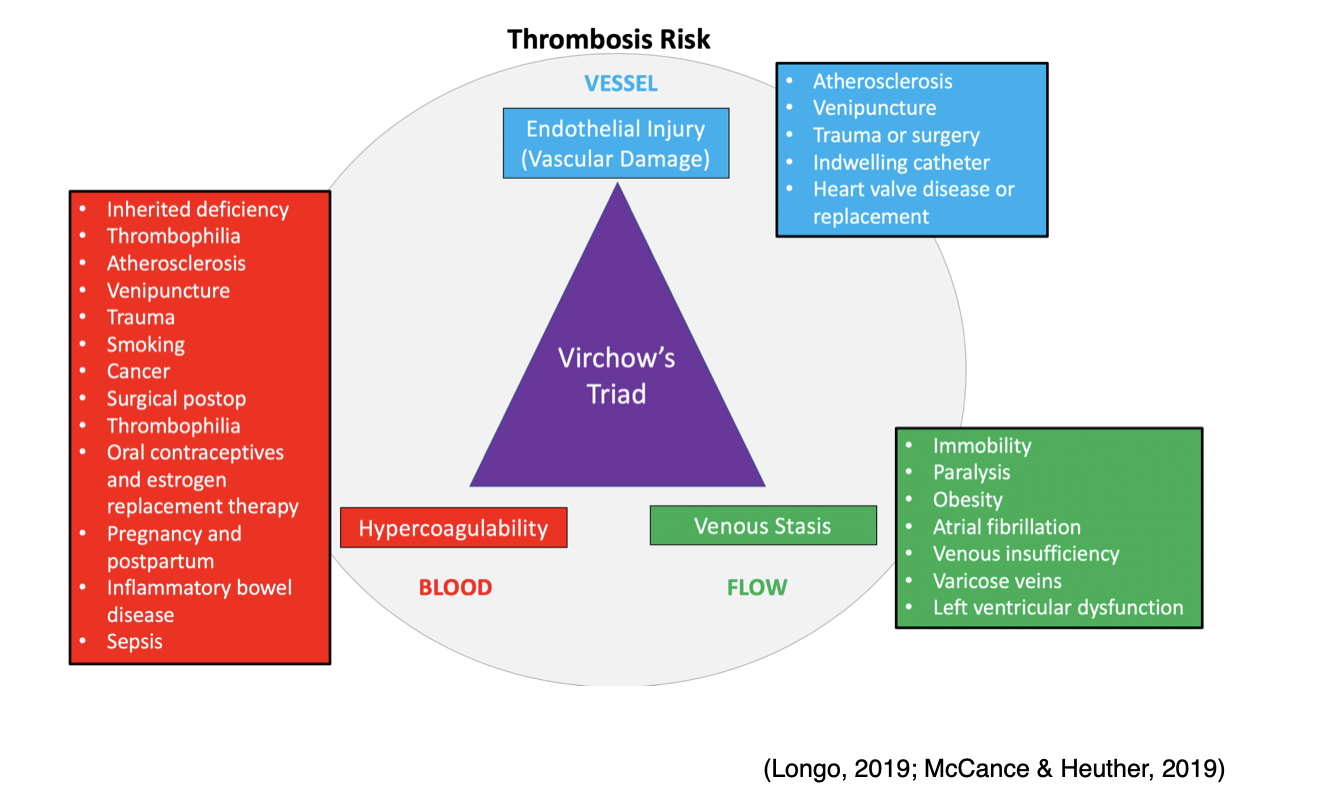

Virchow’s Triad

Rudolf Virchow, often referred to as the "father of modern pathology," is a 19th Century physician credited with identifying three significant predisposing abnormalities that can lead to the development of thrombosis. Branded "Virchow's triad," the three pathologic mechanisms influencing blood clot formation are listed below and explained within Figure 8:

- Damage to the blood vessel wall;

- Blood flow abnormalities;

- Hypercoagulability of the blood (McCance & Heuther, 2019).

Figure 8

Virchow’s Triad

Endothelial Injury

As described earlier, vascular endothelial injury under physiologic conditions leads to platelet activation and blood clot formation to prevent blood loss and restore the integrity of the vascular wall. However, when these mechanisms are impaired, or there is an underlying defect, pathologic consequences can ensue. Endothelial injury can be precipitated by numerous insults that extend beyond external tissue trauma, such as smoking, surgery, atherosclerotic disease, inflammation, or chronic elevations in blood pressure. Regardless of the precipitating event, when the endothelium is injured, normal blood flow is altered, inducing "turbulence" within the vessel. Turbulence is defined as the increased rate of blood flow over the injured surface, generating disordered current and increased friction within the vessel. Atherosclerotic plaques from hyperlipidemia commonly generate turbulent environments within blood vessels (McCance & Heuther, 2019).

Venous Stasis

Venous stasis refers to the loss of blood flow within the vessel. Blood pooling is a tremendous risk factor for thrombus formation, as, during venous stasis, platelets remain in contact with the endothelium for a prolonged period. During this time, clotting factors that would usually be diluted with flowing blood become concentrated and potentially activated. As listed above in Figure 8, the most common conditions that predispose patients to venous stasis include immobility, paralysis, venous insufficiency, varicose veins, obesity, heart failure, and low cardiac output (McCance & Heuther, 2019).

Hypercoagulability

Abnormalities within the coagulation cascade, fibrinolytic pathways, and/or platelet function contribute to hypercoagulability and subsequent thrombus formation. Hypercoagulability may result from hereditary or acquired etiologies and is usually multifactorial, with lifestyle and environmental factors playing key roles. Hypercoagulability resulting from inherited defects includes Factor V Leiden (FVL), prothrombin mutation (G20210A), or deficiencies of the natural proteins that prevent clotting described within the next section of this module. Some individuals may present with increased levels of certain clotting factors without any identifiable genetic mutation. The most common causes of acquired hypercoagulability include cancer, inflammation, immobility from paralysis or prolonged bed rest, surgery (especially the immediate postoperative period), pregnancy, and the postpartum period. Certain medications are known to increase the coagulability of the blood, such as oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy (McCance & Heuther, 2019). Additional risk factors for thrombus formation that extend beyond those identified within Virchow’s triad include the following:

- Personal history of blood clots;

- Family history of blood clots (even without an identifiable inherited disorder);

- Hypertension (high blood pressure);

- Chronic inflammatory diseases;

- Diabetes;

- Age (increased risk in people over the age of 60);

- Presence of multiple concurrent risk factors (i.e., smoking cigarettes while taking oral contraceptive medications) (Longo, 2019).

Thrombosis can be provoked or unprovoked, which is essential for determining the duration of therapy. Unprovoked implies that no identifiable risk factor or underlying cause is evident or identifiable; a provoked thrombus is one that is caused by a known event, such as surgery or prolonged immobility. Unprovoked events are considered more serious and require specific diagnostic workup and treatment, usually under the care of a hematologist (Lip and Hull, 2020).

Arterial vs. Venous Thrombosis

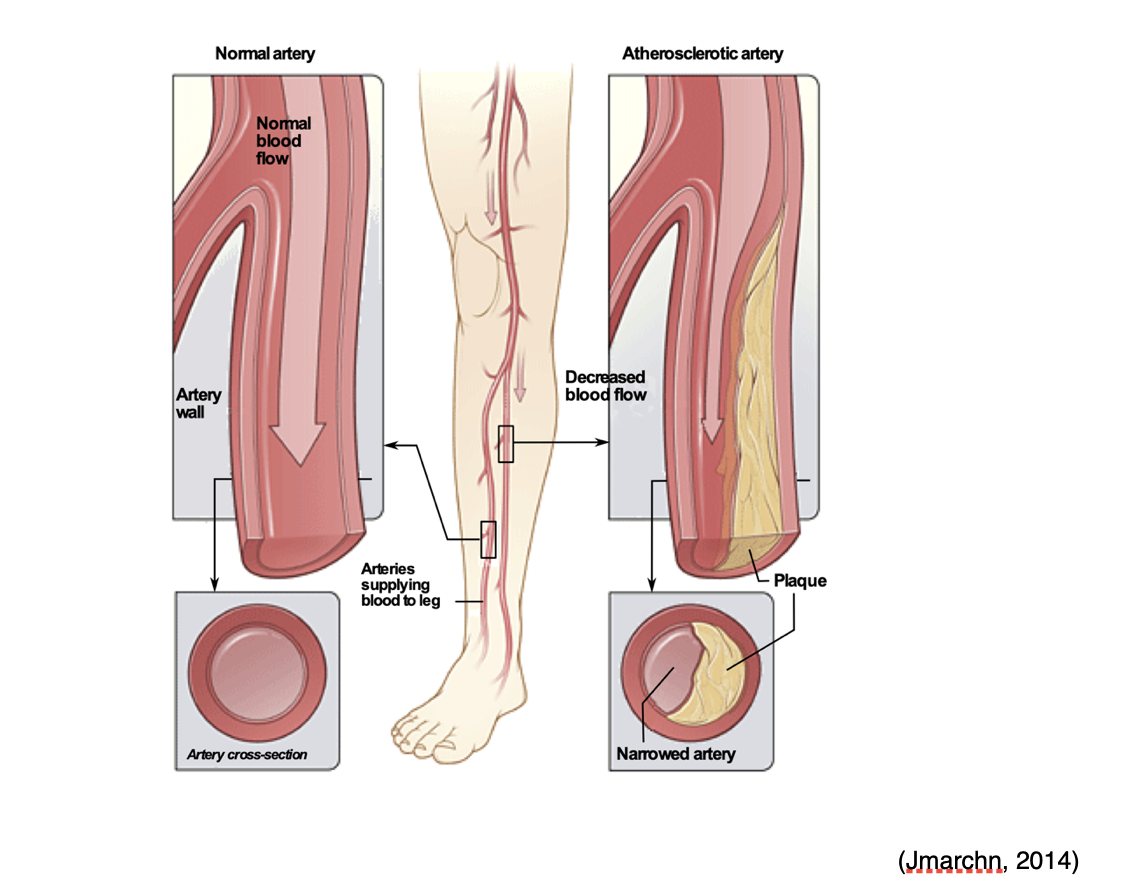

A thrombus can develop anywhere within the cardiovascular system, with the majority classified as venous (within a vein) or arterial (within an artery). Arteries are the blood vessels responsible for carrying oxygen-rich blood away from the heart to the body tissues, whereas veins are the blood vessels that carry blood back to the heart. Venous thrombosis is also called venous thromboembolism (VTE) and includes two major types; deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and superficial vein thrombosis (SVT). DVT is the most common type, arising in the large veins of a lower extremity. Arterial thrombi almost always arise from the heart (i.e., aorta, coronary arteries) but may also occur in the brain's cerebral arteries. Arterial thrombosis is commonly caused by arteriosclerosis, a condition in which a fatty substance called plaque builds up along the walls of arteries. This plaque formation hardens and narrows arteries, and the plaque can crack or rupture, attracting platelets and eventually leading to the formation of blood clots. While thrombi vary in shape and size, they all commonly retain an area of attachment to an underlying vessel or heart wall. The distinguishing features and characteristics of venous and arterial thrombi are outlined in Table 2 (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI], n.d.b).

Table 2

Comparison of Venous and Arterial Thrombi

Venous Thrombosis | Arterial Thrombosis |

More common than arterial thrombosis | Less common than venous thrombosis |

Occur in sites of venous stasis: slow moving blood | Begin at site of endothelial injury or turbulence: rapid blood flow |

Tend to extend in the antegrade direction (direction of blood flow toward the heart) | Tend to grow in retrograde direction (away from the heart) from the point of attachment |

Mixed or red type in color Composed mostly of fibrin and more RBCs due to sluggish blood flow | Pale/white in color Composed of mostly platelets with some fibrin, RBCs, and WBCs |

Not firmly attached and prone to fragment (easily detach and embolize) | Firmly adhered to the injured endothelial wall, however embolus is possible. |

(Longo, 2019; UNC Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center, n.d.)

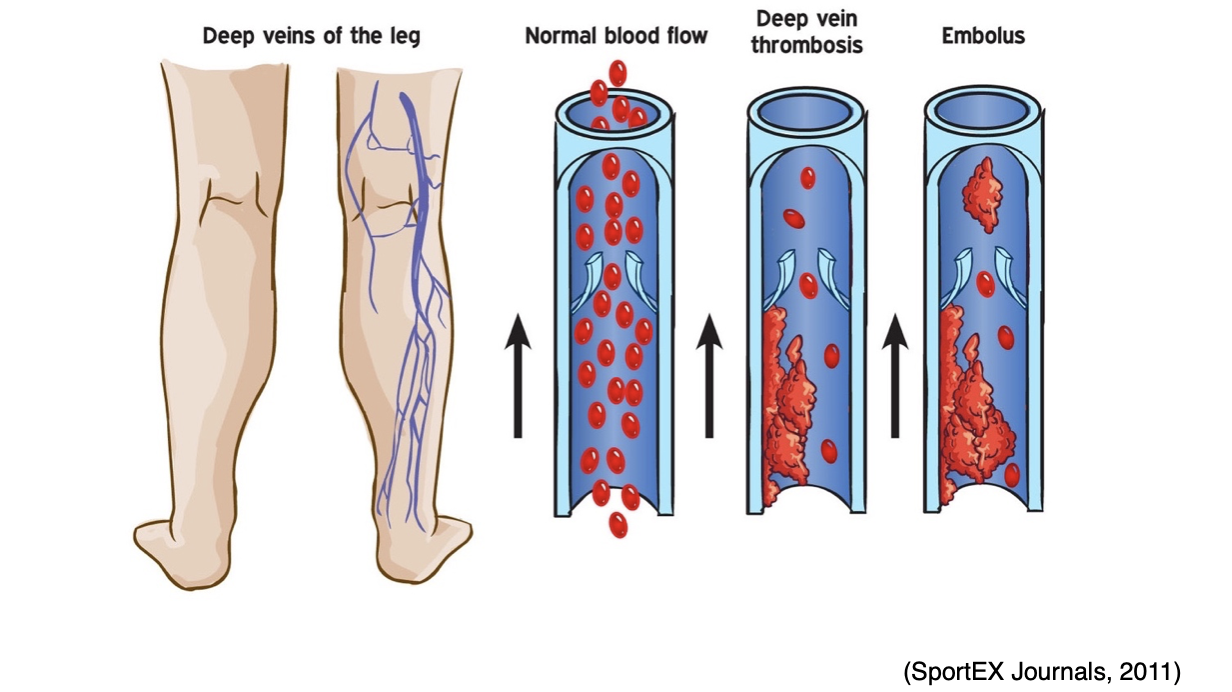

Complications of Venous Thrombosis

Since thrombosis can block the blood flow in both veins and arteries, complications depend on the clot's location. The most serious and dangerous complication of a VTE is a pulmonary embolism (PE), or a blood clot within the lung. A thrombus detaches from the vessel wall and circulates within the bloodstream, causing a sudden blockage of a vessel called an embolism. As demonstrated in Figure 9, a PE is most commonly caused by DVT, as a piece of the blood clot within the extremity breaks off, travels through the veins, and becomes lodged in the lung's blood vessels. A PE can completely obstruct blood flow and induce sudden death in some patients. It can also cause hypoxia or low oxygen levels in the blood, which can lead to permanent damage to the lungs or other organs in the body due to receiving insufficient oxygen (McCance & Heuther, 2019).

Figure 9

DVT

VTE can also lead to serious long-term complications, including post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS), which is the most common complication of a DVT. PTS causes chronic pain and swelling in the affected extremity and, in severe cases, can lead to venous ulcers. Less commonly, some patients can develop chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) in which abnormally high blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs causes the right side of the heart to work harder than normal, leading to heart failure (McCance & Heuther, 2019).

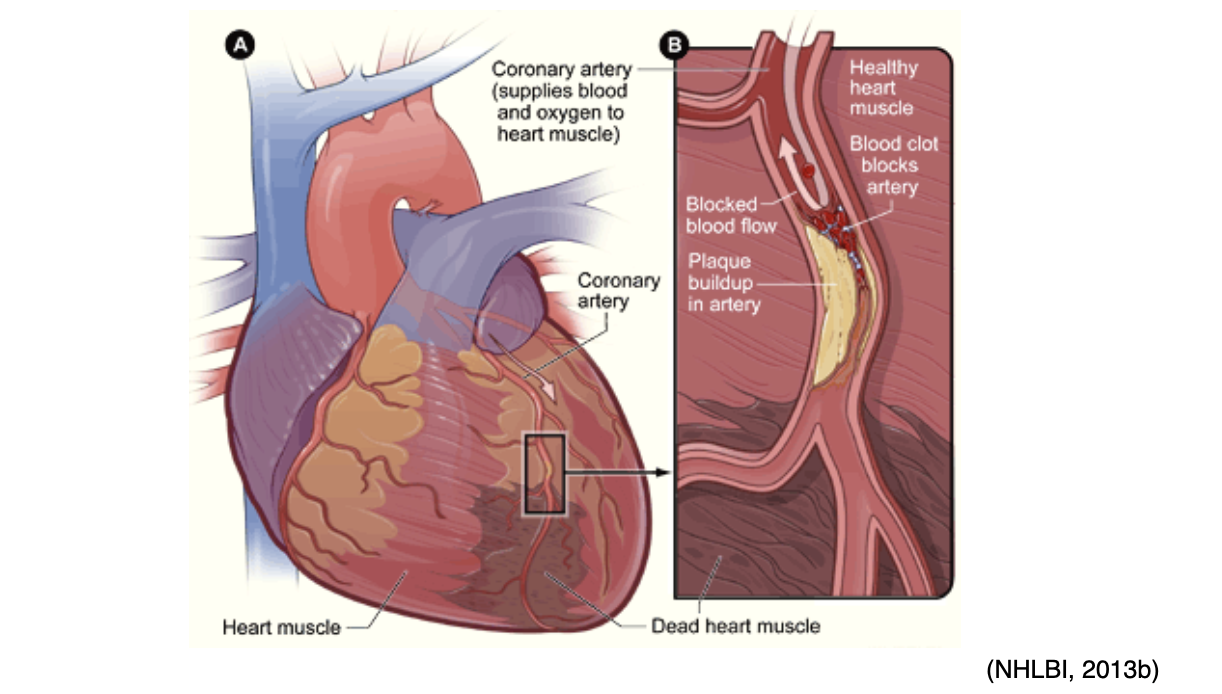

Complications of Arterial Thrombosis

Arterial thrombosis and emboli can cause tissues to become starved of blood and oxygen, leading to necrosis and infarction of vital tissue and organs (heart, brain, kidney, spleen). As shown in Figure 10, a coronary thrombosis is a blockage that occurs within an artery of the heart and causes a myocardial infarction (MI) or heart attack (McCance & Heuther, 2019).

Figure 10

Coronary Thrombosis Inducing a Myocardial Infarction

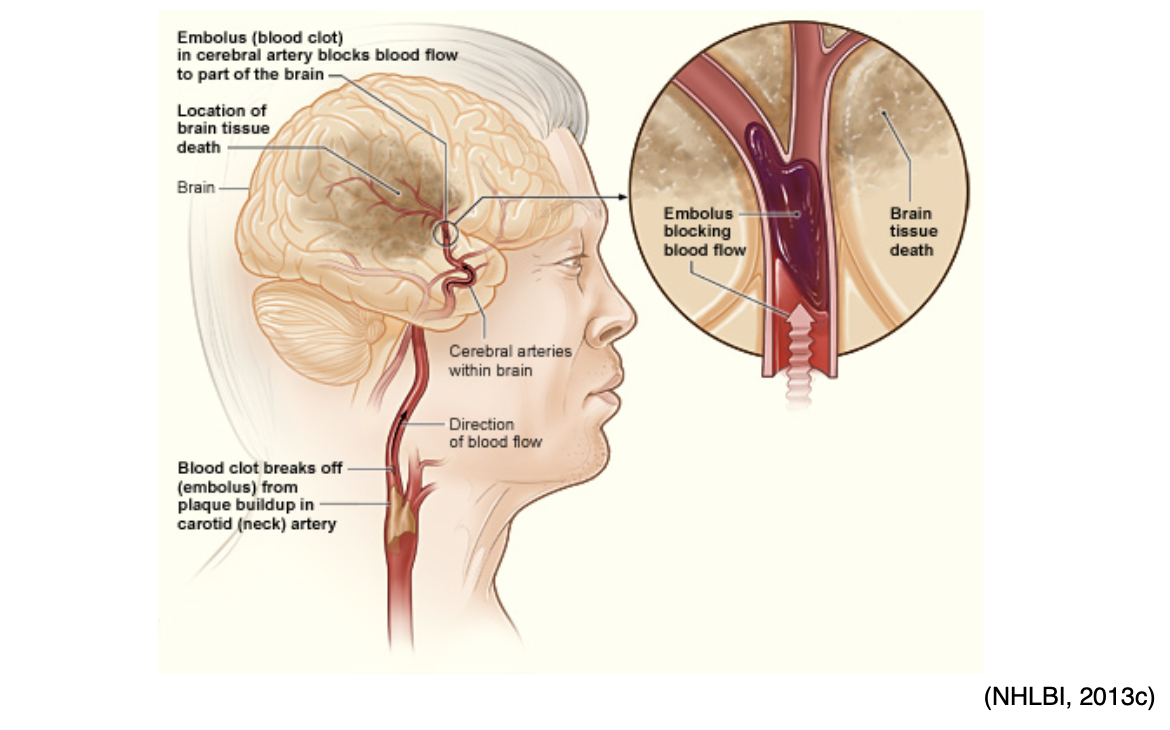

Arterial thrombosis can also cause an ischemic stroke, which occurs when cerebral blood flow is reduced to critical levels or stopped altogether, as demonstrated in Figure 11. An ischemic stroke can either be caused by a thrombus that originates within an artery that supplies blood to the brain, or an embolus that becomes lodged in and blocks an artery that supplies blood to the brain. In both types of ischemic stroke, the plaque or clot keeps oxygen-rich blood from getting to a portion of the brain, and neurons deprived of oxygen start to die within minutes (NHLBI, n.d.b).

Figure 11

Embolic Stroke

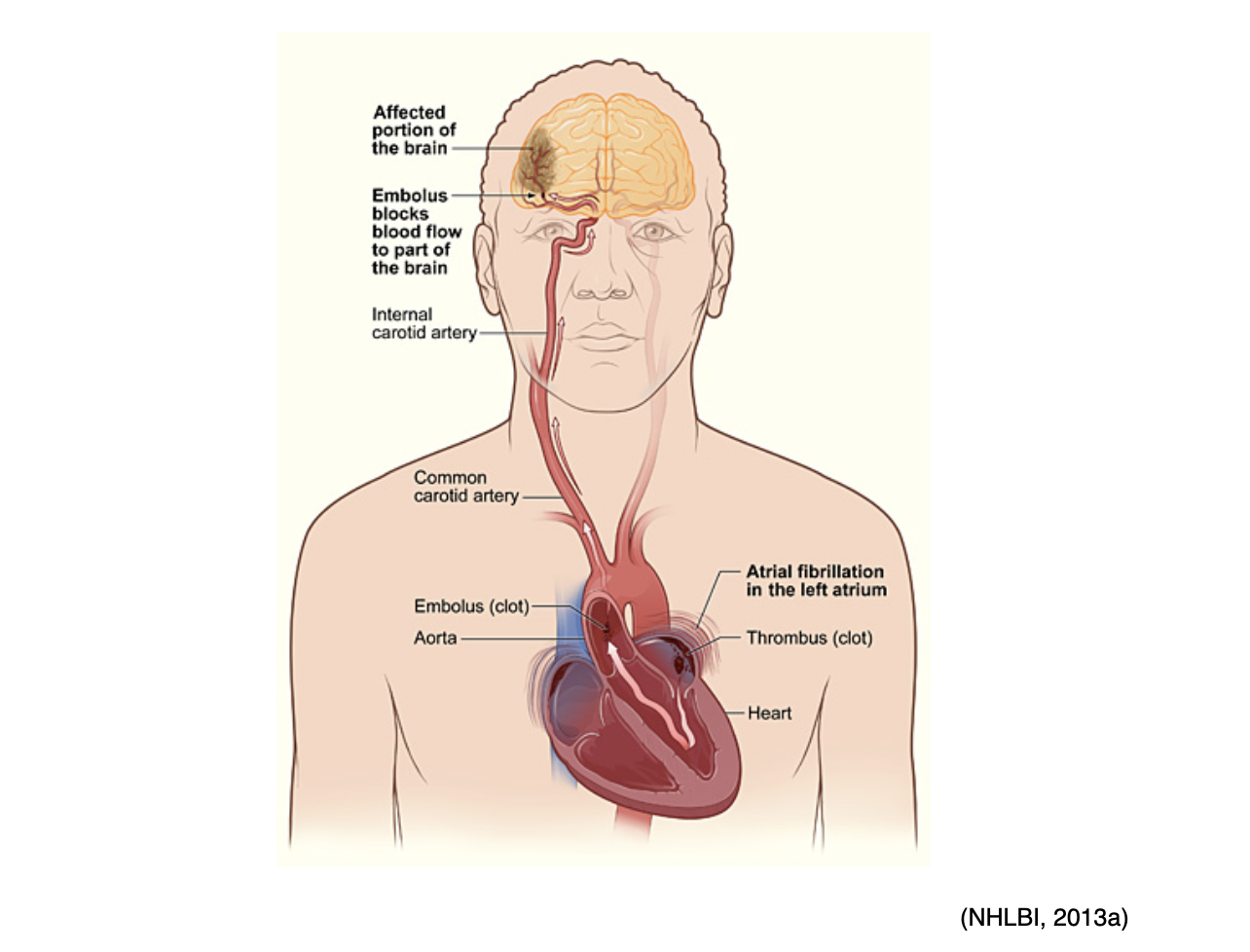

Ischemic stroke is most commonly caused by atherosclerosis but can also be due to atrial fibrillation (Afib), a type of cardiac arrhythmia. Afib is characterized by an irregular rhythm in which blood is not appropriately pumped out of the heart, leading to periods of blood pooling within the heart's atrium. This increases the risk of embolic stroke if a blood clot forms there and is then expelled and travels up to the brain, as portrayed in Figure 12 (McCance & Heuther, 2019; NHLBI, n.d.b).

Figure 12

Atrial Fibrillation-Induced Embolic Stroke

Arterial emboli can also occur in the periphery, such as the legs and feet, reducing blood flow or causing acute ischemia of the lower limbs. This can occur in one of two ways; from arterial embolism or from an arterial thrombus induced by an atherosclerotic artery (atheroembolism) within the extremity, which is demonstrated in Figure 13. When emboli originate in the heart, greater than 70% will obstruct the lower limbs. The femoral artery at the femoral bifurcation is the most common site affected, accounting for 35 to 50% of all cases. Other arteries of the lower extremity commonly affected include the popliteal, iliac, and the aorta. Complete obstruction of blood flow can lead to gangrene, in which the extremity becomes cold, painful, and eventually turns black from necrosis or cell death. In these cases, patients usually require amputation (Casas, 2019).

Figure 13

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Signs and Symptoms of Thrombosis

Since thrombosis can lead to significant morbidity and mortality, resulting in serious and life-threatening consequences, early identification and intervention are essential. The APRN should be well-versed in the most common symptoms and symptoms, which can vary depending upon the location of the body affected. The most common signs and symptoms according to the affected body part are outlined below in Table 3.

Table 3

Common Signs and Symptoms of Thrombosis

Diagnosis | Affected Body Part | Symptoms |

DVT | Extremity (arm or leg) |

|

PE | Lung |

|

Coronary thrombosis | Heart |

|

Stroke | Brain |

|

Arterial Embolism of Lower Limb | Lower extremity |

|

(Casas, 2019; The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020b; Longo, 2019; McCance & Heuther, 2019)

Diagnostic Approach to the Patient with Thrombosis

The diagnostic approach to a patient with suspected thrombosis is based on their presenting signs and symptoms. If an arterial thrombosis or pulmonary embolism is suspected, the diagnostic workup is emergent, critical, and potentially lifesaving. It should be geared toward appropriate management of the suspected condition (i.e., stroke or MI) to reduce morbidity and mortality, and improve clinical outcomes. The diagnostic approach to the patient presenting with clinical suspicion for thrombosis is beyond this module's scope or intent. However, for information regarding the diagnostic workup for these conditions, please refer to the following NursingCE.com courses:

- The Diagnosis, Management, and Rehabilitation of the Acute Stroke Patient

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Acute Myocardial Infarction

Pharmacological Therapy for Thrombosis

Once a thrombosis has been diagnosed, anticoagulation is the mainstay treatment for the management and prevention of blood clots. Anticoagulants commonly referred to as "blood thinners," function to reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality associated with thrombotic events by helping to prevent and/or dissolve existing blood clots, as well as slow down the body's process of generating new blood clots (Witt et al., 2018).

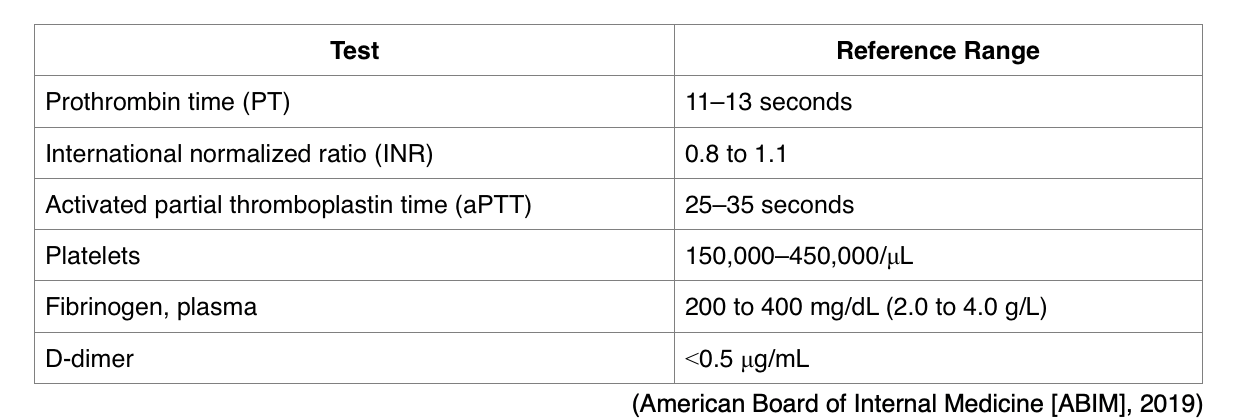

Monitoring and Safeguarding Patients from Adverse Events

While anticoagulation therapy can be lifesaving for many patients, it can also pose serious risks for life-threatening bleeding events. The ASH (2018) advises clinicians to first acquire a comprehensive understanding of anticoagulation therapy principles, including the clinical implications of routine laboratory monitoring, to ensure there is an optimal balance between its therapeutic properties and its risks for serious bleeding. The most common indicator for evaluating a patient's risk for bleeding is through a series of laboratory tests, which may be referred to as the coagulation profile, as shown in Table 4 (Witt et al., 2018).

Table 4

Coagulation Profile

One of the most common reasons for performing PT/INR testing is to monitor warfarin (Coumadin) levels. Higher than normal PT/INR levels indicate a higher risk for bleeding events due to the body's impaired ability to clot blood. While on warfarin (Coumadin), it is essential that the PT/INR does not exceed therapeutic thresholds; otherwise, the risk for bleeding heightens. The aPTT test is commonly performed alongside the PT/INR when evaluating patients with suspected bleeding or blood clotting disorders. While the PT test assesses how well all of the coagulation factors in the extrinsic and common pathways of the coagulation cascade are functioning collectively, the aPTT evaluates the clotting factors within the intrinsic and common pathways. Therefore, the functioning of the extrinsic pathway is best evaluated monitored using the PT/INR test, whereas the intrinsic and common pathways are best monitored using the PTT/aPTT test (AACC, 2019).

Fibrinogen can be measured in two ways:

- A fibrinogen antigen test measures the amount of fibrinogen in the blood, as shown in Table 4, or

- A fibrinogen activity test, done less commonly, evaluates how well fibrinogen functions in helping to form a blood clot.

D-dimer is a protein fragment that is produced when the body is forming or breaking down blood clots. Under physiologic conditions, the D-dimer level is usually undetectable, or at very low levels; the levels can increase when there are significant formation and breakdown of fibrin clots in the body. Therefore, the D-dimer test measures the amount of the substance released into the bloodstream when fibrin proteins in a blood clot dissolve (USDHHS, n.d.). The d-dimer test is commonly used as a screening test for VTEs, as a negative (low or undetectable) D-dimer test indicates that it is highly unlikely that a thrombus is present. However, the test is not specific, as a positive D-dimer test (elevated levels) cannot definitively predict whether or not a clot is present. While a positive D-dimer can indicate an abnormally high level of fibrin degradation products, raising clinical suspicion for a thrombus formation or breakdown in the body, it does not tell the location or etiology (AACC, 2020). The American Society of Hematology (ASH) 2018 guidelines warn against a high rate of false-positive results with D-dimer testing, especially in certain patient populations such as post-surgical or pregnant patients (Lim et al., 2018).

Patient Education

Due to the risk of adverse bleeding events while on anticoagulation therapy, all patients on anticoagulants should receive supplementary education that begins before prescribing anticoagulation therapy and continues on an ongoing basis throughout treatment. Clinicians are responsible for ensuring that patients are extensively counseled about the potential risk for bleeding events while taking these high-risk medications. Patients should be provided with information regarding the major complications of anticoagulation therapy and the importance of monitoring for and reporting any adverse effects. The major complications include blood clotting due to under-dosing (or subtherapeutic dosing) or bleeding due to excessive anticoagulation. The most serious bleeding includes gastrointestinal and intracerebral bleeds, although excessive bleeding can occur in any area. Patients taking warfarin (Coumadin) should report any falls or accidents and signs or symptoms of bleeding or unusual bruising. Patients should be advised to monitor for signs of abnormal bleeding while on anticoagulation therapy and to seek medical attention for any of the following:

- Fall or head injury;

- Headache that is more severe than usual, confusion, weakness, or numbness, which can be signs of signal intracerebral bleeding;

- Hemoptysis;

- Hematemesis;

- Bleeding that will not stop (American Heart Association [AHA], 2016; Witt et al., 2018).

Type and Duration of Anticoagulation Therapy

The choice of anticoagulant therapy is based on several factors, including the severity of thrombosis or thrombophilia disorder, patient and clinician preference, adherence to therapy, and potential drug and dietary interactions. The 2018 ASH guidelines do not specify which medication is preferred for VTE treatment, but instead, guide the use of the different groups of medications and their clinical considerations. The reversal of each anticoagulant and management of bleeding is also specific to each type of therapy. The duration of anticoagulant therapy depends upon the etiology of the condition, if the thrombotic event was provoked or unprovoked, specific patient clinical risk factors, and the presence of any comorbid conditions (Witt et al., 2018).

Benefits of treatment include prevention of clot extension, a PE, recurrent VTE, hemodynamic collapse, and even death. Surgical patients who develop VTE postoperatively are considered low risk (< 1% after one year, 3% after five years) for recurrence. Patients with VTE not related to surgery but instead associated with pregnancy, prolonged immobility, or exogenous estrogen therapy are considered intermediate risk for recurrence (5% after one year, 15% after five years). Both low and intermediate-risk patients can be treated with anticoagulant medication for three months. The risk for recurrence is higher for high-risk patients (those with unprovoked or cancer-related VTE). Cancer patients have a 15% recurrence rate and should be treated until cured and for at least six months. Patients with unprovoked VTE have a 10% risk of recurrence after one year and 30% after five years. They should be treated indefinitely if their bleeding risk is low to intermediate or for three to six months if they are high-risk for bleeding. Men are at twice the risk for recurrence as compared to women (Tritschler et al., 2018).

In general, anticoagulation is recommended for a minimum of three months in patients with VTE. Patients who have endured their first provoked DVT will likely be treated with anticoagulation for at least three months or until the risk has resolved. For patients with unprovoked episodes of VTE, who have a low to moderate bleeding risk, long-term treatment is recommended to prevent a recurrence, which can be prescribed for six months, or up to an indefinite period depending upon the clinical risk factors and underlying conditions (Tritschler et al., 2018). Most experts and clinical guidelines support the continuation of chronic anticoagulation therapy for patients with two or more venous thrombosis episodes or if a risk factor for clotting persists (Pai & Douketis, 2020). In patients on anticoagulation therapy for arterial clots, the duration of therapy is more complex and depends upon the clinical circumstances as well as the patient's underlying risk factors. Most anticoagulation therapies for arterial thrombosis are continued for significantly longer durations such as two to five years, or indefinitely. Some patients may be prescribed chronic oral anticoagulation, followed by lifelong aspirin [acetylsalicylic acid (ASA)] therapy. However, these guidelines are more fluid and less finite than those available for VTEs (Fredenburgh et al., 2017).

Treatment of inherited thrombophilia disorders varies widely and is usually based on the patient's medical history and clinical manifestations. However, patients who have never developed an abnormal blood clot are not routinely or prophylactically treated with anticoagulant therapy across most of these conditions. However, those who have had a prior blood clot are usually prescribed anticoagulant therapy, with the average treatment lasting three to six months. The decision to continue anticoagulation therapy beyond this timeframe or indefinitely depends on whether the thrombosis was provoked or unprovoked and other clinical risk factors. For the vast majority of patients, lifelong treatment with anticoagulant therapy is generally not advised unless there are other critical risk factors (GARD, 2017a).

Vitamin K Antagonists (VKA)

VKAs are the oldest class of oral anticoagulants and have a variety of medical indications beyond the treatment and prevention of VTEs, such as AFib, ischemic stroke, acute MI, patients with mechanical prosthetic cardiac valves, and patients undergoing orthopedic surgery. VKAs are also used as prophylaxis for VTE in high-risk patient populations, such as those with embolic peripheral and arterial disease. VKAs prevent coagulation by suppressing the synthesis of vitamin K-dependent factors. In other words, they act as antagonists to vitamin K, impairing the liver's ability to process vitamin K into clotting factors, thereby curbing blood clotting. The goal of VKA therapy is to decrease the clotting tendency of blood, but not to prevent clotting entirely. There are several types of VKAs, such as warfarin (Coumadin), acenocoumarol (Ascumar), phenprocoumon (Marcoumar), and coumatetralyl (Racumin). However, warfarin (Coumadin) is the most well-known and widely used oral anticoagulant in the US and will be the focus of discussion within this section (Tritschler et al., 2018).

Patients who are prescribed warfarin (Coumadin) require ongoing monitoring for therapeutic levels of the drug as vitamin K is found in many foods such as green leafy vegetables and certain oils. If the consumption of vitamin K-rich foods increases, the patient will require higher warfarin (Coumadin) dose to maintain therapeutic levels. Similarly, the contrary is also true; with reduced intake of foods rich in vitamin K, the warfarin (Coumadin) dose may need to be reduced to prevent bleeding. Therefore, patients should be advised to maintain a balanced diet with regards to the amount of vitamin K intake weekly. Similarly, if patients skip a dose (or take an extra dose) of warfarin (Coumadin), the warfarin (Coumadin) level may be altered for several days, as both vitamin K and warfarin (Coumadin) levels rise gradually. In addition, there are several other special considerations with regards to dietary and medication interactions while on warfarin (Coumadin) therapy. Various medications, dietary supplements, and herbal preparations can interfere with the metabolism of warfarin (Coumadin), which can lead to increased risk for bleeding or reduced efficacy of the medication, thereby increasing the risk for blood clot formation. Therefore, patients must be counseled on the importance of reporting any new medications or dietary preparations prior to starting to ensure that there are no potential interactions. Some of the most common interactions include the following:

- Common drug interactions:

- Acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin)

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (Motrin)

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol)

- Antacids

- Laxatives

- Numerous types of antibiotics

- Antifungal medications such as fluconazole (Diflucan)

- Antiarrhythmic medications such as amiodarone (Pacerone)

- Common herbal preparations and dietary supplement interactions:

- Coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinone)

- Garlic

- Ginkgo biloba

- Ginseng

- Green tea

- St. John's wort

- Vitamin E

- Aside from vitamin K, other foods and drinks that can potentially interact with warfarin (Coumadin) include the following:

- Cranberries or cranberry juice

- Grapefruit or grapefruit juice

- Alcohol

- Black licorice (Mayo Clinic, 2020).

The frequency of INR monitoring is fluid and depends on the patient, their clinical risk factors, the reason for VKA therapy, as well as the patient’s comorbid conditions. For patients with a VTE, the recommendation is to initiate treatment with a parenteral anticoagulant treatment first to obtain faster therapeutic anticoagulation, while starting warfarin (Coumadin) with a 10 mg dose on days one and two, followed by dosing based on INR results from day three forward (Tritschler et al., 2018).

The target INR for patients with VTE is usually between 2 and 3, except in patients who develop recurrent VTE while on VKA or DOAC therapy, at which time the target INR is 3.5. In patients receiving warfarin (Coumadin) for VTE treatment, ASH recommends following an INR monitoring interval of four weeks or less. In patients receiving maintenance VKA for the treatment of VTE, a longer interval of 6 to 12 weeks is recommended once stable INR control has been obtained. In patients receiving maintenance VKA therapy for the treatment of VTE, the ASH (2018) recommends using patient self-testing (PST) of INR with home point-of-care monitoring in patients who have demonstrated competency to perform and afford this (Witt et al., 2018).

VKAs are contraindicated in patients with hemorrhagic stroke or clinically significant bleeding. Use should also be avoided within 72 hours of major surgery due to the risk of severe bleeding. As with most medications and medical treatments, complications may arise with the use of anticoagulant medications, and for anticoagulant therapy, the primary potential complication is bleeding. In patients on VKA, this may present as an unsafe/highly elevated INR (above 4.5), which may lead to dangerous bleeding. For patients with an INR of 4.5-10 without any clinically relevant bleeding, the ASH suggests discontinuing the medication. However, they do not suggest administering vitamin K. In the case of life-threatening bleeding, 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (PCCS) [Kcentra] with phytomenadione (vitamin K1) 5-10mg should be administered by slow intravenous (IV) injection (Witt et al., 2018). PCCS (Kcentra) is FDA-approved for the urgent reversal of acquired coagulation factor deficiency induced by VKA therapy in adult patients with major bleeding. Available as a single-use injection, dosing is based on the INR value and the patient's body weight. Vitamin K should be administered concurrently with PCCS (Kcentra) to maintain therapeutic factor levels once the effects of PCCS (Kcentra) have diminished. Since PCCS (Kcentra) is generated from human blood, it carries a risk of transmitting infectious agents, particularly human viruses, as well as hypersensitivity reactions. The most common adverse reactions include headache, nausea, vomiting, arthralgia, hypotension, and rarely thromboembolic events, including stroke, PE, and DVT (FDA, 2018).

Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOAC)

DOACs are a relatively novel anticoagulation therapy group that is as safe and effective as VKAs across randomized clinical trials for the management of VTE. They are also approved for patients at risk for thromboembolic complications, such as ischemic stroke, and prophylaxis and treatment of DVT and PE. DOACs work by directly inhibiting specific proteins within the clotting cascade. Compared to warfarin (Coumadin), DOACs have fewer drug interactions and seem to produce a more predictable, less labile anticoagulant effect. However, DOACs differ in their reliance on the kidneys for elimination and frequency of administration. There is limited data available to guide clinical decision making about the best approach to reverse the anticoagulant effects of DOACs (American Society of Health-System Pharmacists [ASHP], n.d.).

DOACs are classified into two basic categories; direct thrombin inhibitors and factor Xa inhibitors. Dabigatran (Pradaxa) is a direct thrombin inhibitor that exerts its anticoagulant effects by binding directly to thrombin, thereby inhibiting both soluble and fibrin-bound thrombin. Since thrombin enables the conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin during the coagulation cascade, its inhibition prevents thrombus development. Rivaroxaban (Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), and edoxaban (Savaysa) are oral direct factor Xa inhibitors, which work by selectively and reversibly blocking the activity of FXa, thereby preventing clot formation. They affect FXa presence within the bloodstream and within a preexisting clot, but they do not affect platelet aggregation. The 2016 American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and 2017 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend the use of DOACs over other medications as they have been proven to be non-inferior in terms of efficacy with an improved safety profile based on a reduced risk of major bleeding as compared to warfarin (Coumadin). They also carry the added advantage of a rapid onset of action and a predictable pharmacokinetic profile, which negates the need for monitoring and dose adjustments. If using dabigatran (Pradaxa), they recommend using LMWH for at least five days first, whereas rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and apixaban (Eliquis) do not require antecedent treatment with LMWH. DOACs should be avoided in patients with concomitant medications that are potent p-glycoprotein inhibitors or cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors or inducers. This includes azole antimycotics like ketoconazole (Nizoral), several protease inhibitors used for HIV, and antiepileptics such as phenytoin (Dilantin) and carbamazepine (Tegretol; Tritschler et al., 2018).

With direct factor Xa inhibitors, no monitoring is required to ensure therapeutic drug levels, however routine monitoring of CrCl is recommended, and these agents should be discontinued if CrCl < 15ml/min. Other common adverse effects of direct factor Xa inhibitors include nausea, bruising, and anemia. Less commonly, patients can experience hypotension, thrombocytopenia, or skin rash. With dabigatran (Pradaxa), clinical data is limited in patients with CrCl 30-50ml/min, and there is also limited data for its use in patients with a bodyweight < 50kg or > 100kg. Similar to direct factor Xa inhibitors, no monitoring is required to ensure therapeutic levels. However, regular monitoring of CrCl is recommended to avoid an accumulation of dabigatran (Pradaxa) in reduced renal function, and it is recommended that the medication be discontinued if CrCl < 30ml/min. The most common adverse effects include nausea, dyspepsia, diarrhea, abdominal pain, anemia, and hemorrhage. Less commonly, patients can develop gastrointestinal ulcers, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), esophagitis, and thrombocytopenia (Witt et al., 2018).

Currently, idarucizumab (Praxbind) is the only antidote approved by the FDA in 2015 to reverse the anticoagulant effects of dabigatran (Pradaxa); however, it does not reverse the anticoagulant effects of other DOACs. Idarucizumab (Praxbind) is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody fragment that binds specifically to dabigatran (Pradaxa) to inhibit its anticoagulant effects. It does not independently cause hemostasis and is not capable of activating clotting; despite having structural features similar to thrombin, it is not effective for the reversal of other DOACs. Idarucizumab (Praxbind) is administered as two consecutive IV infusions for a standard total recommended dose of 5 g (ASHP, n.d.).

For patients on a DOAC other than dabigatran (Pradaxa) who endure acute, severe, and potentially life-threatening bleeding complications, the ASH recommends stopping the anticoagulant medication and administering 4-factor PCCS (Kcentra) or coagulation factor Xa (recombinant), inactivated-zhzo (andexanet alpha or Andexxa), if on rivaroxaban (Xarelto), edoxaban (Savaysa), or apixaban (Eliquis) (Witt et al., 2018). In most cases of mild-to-moderate bleeding that is not life-threatening, clinicians are advised to simply stop the DOAC and monitor patients closely (Tritschler et al., 2018).

Parenteral Direct Thrombin inhibitors

In addition to the oral agent dabigatran (Pradaxa), there are a few IV direct thrombin inhibitors that have primarily been developed and evaluated for the treatment of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and the management of VTE. These agents include argatroban (Acova), bivalirudin (Angiomax), and lepirudin (Refludan). However, lepirudin (Refludan) was discontinued by the manufacturer in 2012. Argatroban (Acova) is administered via continuous IV infusion, as it has limited bioavailability. It is hepatically cleared and therefore, should be avoided in patients with underlying hepatic dysfunction and impairment. The use of bivalirudin (Angiomax) has only been studied in patients receiving concomitant aspirin therapy. It is administered as an IV bolus or by continuous infusion, and dosing does not require adjustment in patients with hepatic impairment. The continuous infusion dose may need to be adjusted for moderate to severe renal impairment (Leung, 2020a).

Unfractionated Heparin (UFH)

Unfractionated Heparin (UFH) is a rapidly acting anticoagulant agent that collaborates with antithrombin to block clot formation. UFH binds to antithrombin and enhances its ability to inhibit FXa and FIIa quickly. While UFH does not break down clots, it functions to prevent new ones from forming, allowing the body to dissolve any existing thrombi gradually. UFH is administered via subcutaneous injection or as a continuous IV infusion. Dosing is determined by body weight, and patients require frequent monitoring while on treatment with UFH to ensure appropriate dosing and safety. Since UFH does not rely heavily on the kidneys for its excretion, it is considered the treatment of choice for patients who are severely obese or severely underweight, and for patients with underlying renal dysfunction (National Blood Clot Alliance [NBCA], n.d.b.). The primary advantages of UFH include its rapid onset and its relatively rapid termination following discontinuation of the medication. It is the preferred treatment for patients at heightened risk for bleeding due to its short half-life and reversibility. While the definitive half-life of UFH depends on the dose, the average half-life is about 30 to 90 minutes in most healthy adults (Longo, 2019). Protamine sulfate (Prosulf) is commonly used for the reversal of the anticoagulation effect of UFH. In patients on UFH who develop life-threatening bleeding, the ASH recommends stopping the anticoagulant and administering protamine (Prosulf) (Witt et al., 2018). One milligram (mg) of protamine sulfate will neutralize approximately 100 units of UFH. However, since the half-life of heparin is relatively short, the timing of protamine (Prosulf) administration depends on the timing of the most recent UFH exposure. As more time passes from the most recent UFH exposure, the less protamine (Prosulf) is required to reverse its anticoagulant effects (Kantorovich, 2018). Aside from uncontrolled bleeding events, additional potential side effects of UFH include redness and irritation at the injection site, elevations in liver enzymes, reduced bone strength, and HIT. HIT is a potentially life-threatening disorder that occurs in response to the administration of UFH and will be described in greater detail within the section on blood clotting disorders (NBCA, n.d.b.).

Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH)

LMWHs are subcutaneous injections that work by inhibiting thrombin and factor Xa. Some of the most common LMWH agents include dalteparin (Fragmin), enoxaparin (Lovenox), nadroparin (Fraxiparin), and tinzaparin (Innohep). LMWHs are generally preferred over UFH or DOACs for the initial treatment of acute VTE secondary to their once-daily dosing regimen and reduced rate of complications (Schunemann et al., 2018). LMWHs are dosed based on the patient's body weight. ASH guidelines recommend using the patient's actual body weight when calculating the dose, including those with obesity and a body mass index (BMI) > 30. Further, the doses of LMWH should be adjusted for renal function in patients with CrCl < 30mL/min, as advised by the medication's manufacturing label. Alternatively, patients with severe renal dysfunction can be changed to an alternative anticoagulant such as UFH. For patients on LMWH who develop life-threatening bleeding, the ASH recommends stopping the anticoagulant and administering protamine (Prosulf) (Witt et al., 2018).

Fondaparinux (Arixtra) is a factor Xa inhibitor that is chemically related to LMWHs; it is more effective than LMWH in most studies but with an increased risk of bleeding. It works as a synthetic selective factor Xa inhibitor and is most commonly used to manage superficial thrombophlebitis, which can progress to a VTE if left untreated. Many believe they should be treated to avoid progression. Currently, fondaparinux (Arixtra), dosed prophylactically at 2.5 mg/day subcutaneously for 45 days, has the best evidence regarding efficacy and safety versus placebo (Nisio et al., 2018).

Transitioning Between Anticoagulants

The need to transition patients between anticoagulation therapy is a common occurrence that clinicians routinely face at some point in their career. There are specific considerations when transitioning between anticoagulant agents and the guidelines on this topic are constantly changing. For instance, when transitioning from a DOAC to a VKA, the ASH guidelines currently recommend overlapping therapies until the INR is within the therapeutic range. Previously, bridging therapy using LMWH or UFH was advised, but this is no longer considered standard practice. Clinicians are instead advised to measure the INR immediately prior to the next DOAC dose when overlapping therapy. It is essential for clinicians to ascertain a keen awareness of each drug’s half-life when interpreting INR results, as well as the degree of influence DOACs have on the INR. It is essential that clinicians stay up to date on clinical practice guidelines and manufacturer guidelines when transitioning between therapies (Witt et al., 2018).

Clinical Approach to the Patient with Bleeding and Clotting Disorders

When a patient presents with symptoms suggestive of a thrombus, a detailed personal and family history is essential in determining the chronicity of symptoms and the likelihood of the inherited disorder. A complete history can also provide important clues to underlying conditions that may contribute to thrombus formation. One of the important factors related to thrombosis diagnosis is determining if the event is idiopathic or has an identifiable precipitating event. Family history can help determine if there is a potential genetic predisposition and how strong the predisposition may be. Since bleeding and clotting disorders may be inherited or acquired, the APRN must ascertain a detailed personal and family history (Longo, 2019). Since patients with thrombophilic conditions are already at heightened risk for blood clotting, it is essential to mitigate this risk by controlling modifiable risk factors, such as oral contraceptive use, hormone replacement therapy, and smoking. Other factors that increase the risk of blood clots include increasing age, obesity, trauma, surgery, and pregnancy (US National Library of Medicine [NLM], 2020a).

Disorders of Excessive Blood Clotting

Excessive blood clotting disorders, also referred to as hypercoagulable conditions or thrombophilia, are conditions characterized by an increased propensity or predisposition to develop blood clots. These conditions can affect both the venous and arterial circulation systems and may be inherited (genetic) or acquired. The majority of inherited blood clotting disorders affect the venous system, increasing the risk for VTEs (American Association for Clinical Chemistry [AACC], 2019a).

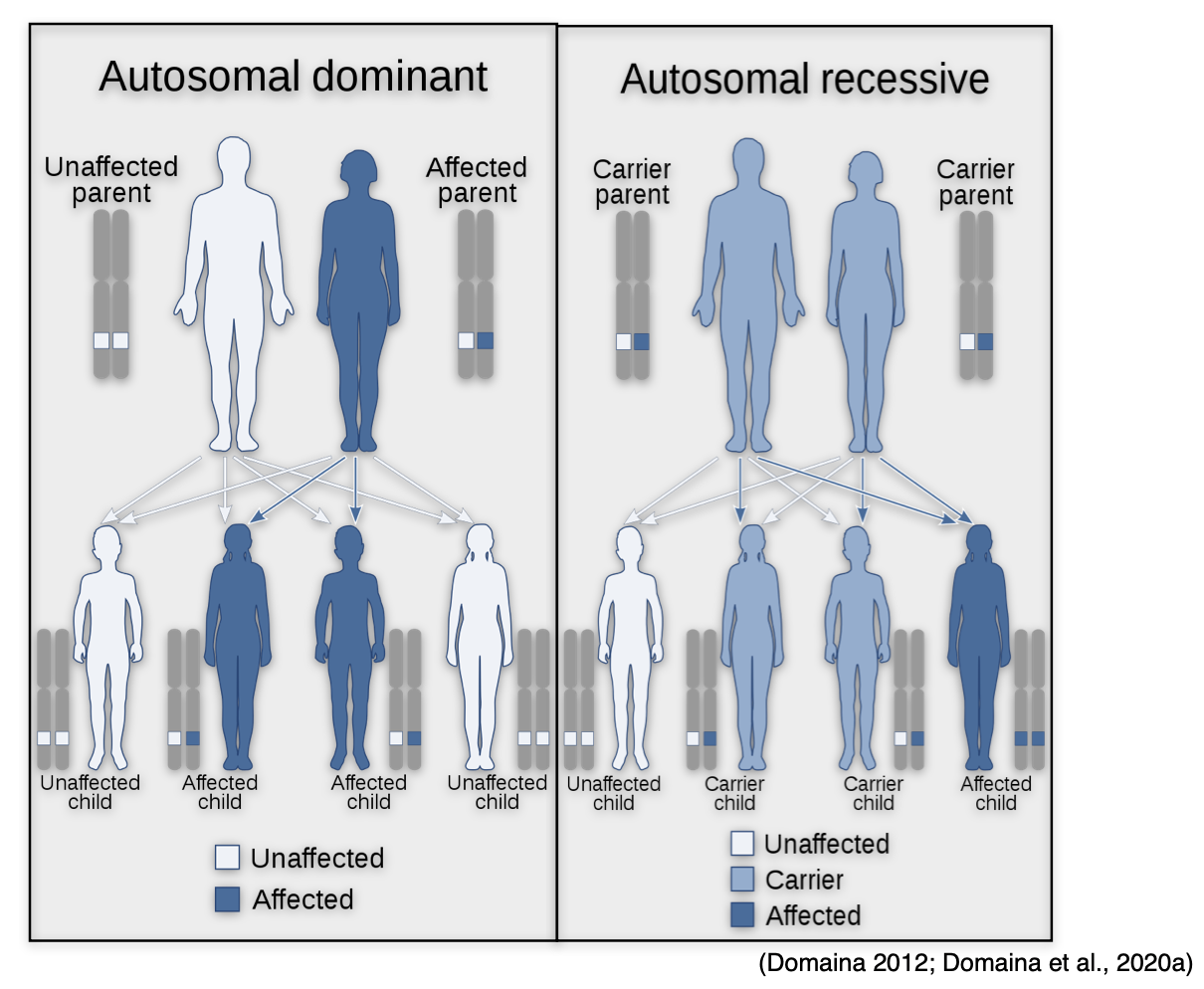

Inheritance Patterns of Disease

To understand the inherited disorders, it is essential to establish a basic understanding of inheritance patterns of these genetic defects. Heterozygous is the term used to describe patients who have a mutation in only one copy of the gene, whereas homozygous describes a patient who has inherited a mutation in both copies of the gene (NLM, 2020e).

Autosomal Dominant (AD)

In conditions that are AD, the abnormal gene is dominant and is located on one of the chromosomes. The term 'dominant' means that the patient only needs one mutated copy of the gene to be affected by the disorder. In some cases, an affected person inherits the condition from an affected parent. In other cases, the condition may develop from a new mutation in the gene and occur randomly in people with no history of the disorder in their family. As demonstrated in Figure 14 (left side), a person with an AD disorder has a 50% chance of having an affected child with one abnormal gene, and a 50% chance of having an unaffected child with two normal genes (NLM, 2020e).

Autosomal Recessive (AR)

In conditions that are AR, one abnormal gene must be inherited from each parent, as the patient requires two copies of the mutation to be affected by the disease. A carrier of the condition has one abnormal gene (recessive) and one normal gene (dominant) but is unaffected by the disorder. Therefore, as demonstrated in Figure 14 (right side), two carriers have a 25% chance of having an unaffected child with two normal genes, a 50% chance of having a child who is an unaffected carrier, and a 25% chance of having a child with two recessive genes affected by the disorder. AR disorders are not usually seen in every generation of an affected family (NLM, 2020e).

Figure 14

Autosomal Dominant vs. Autosomal Recessive Disease Inheritance

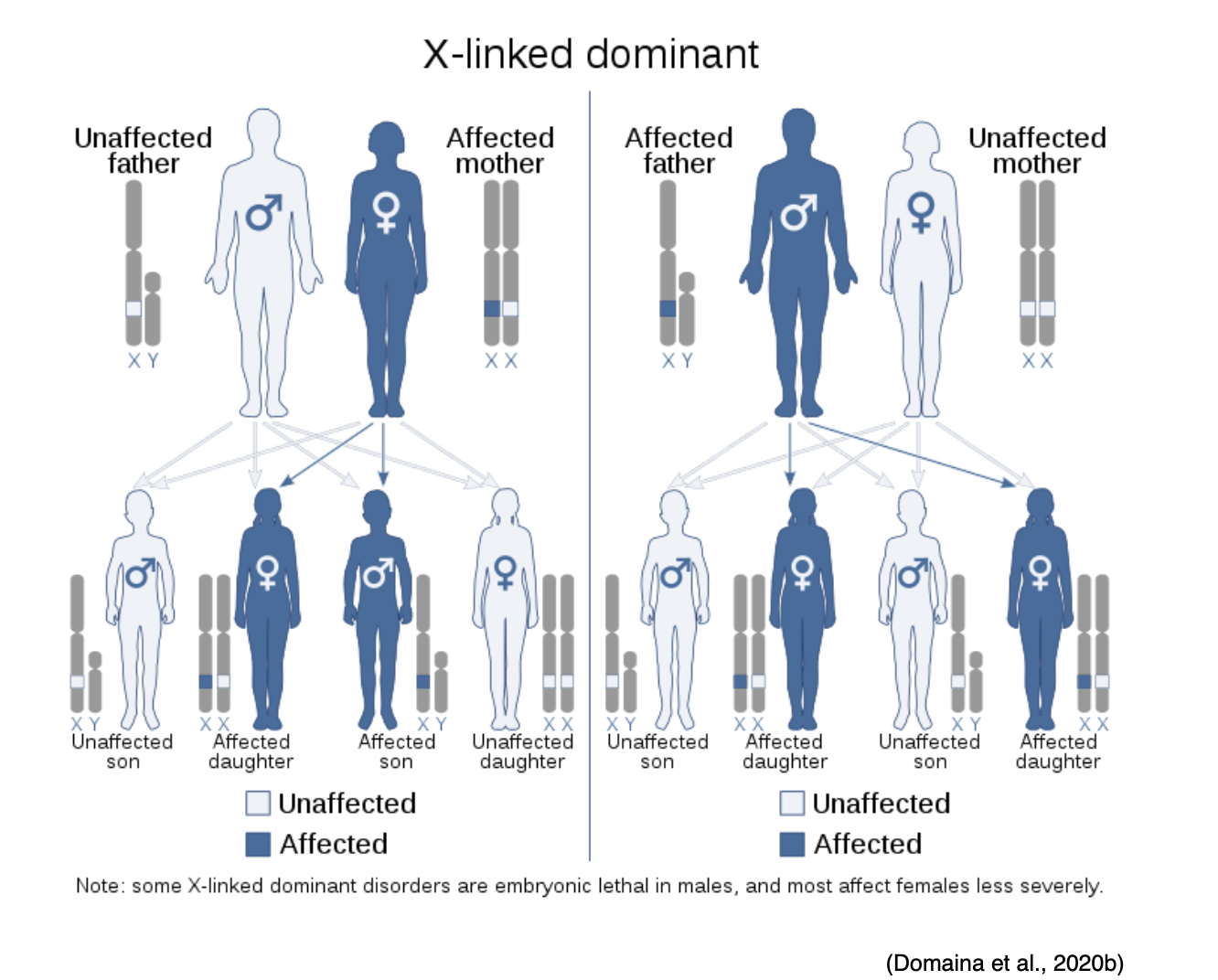

X-linked Dominant

X-linked dominant disorders are caused by mutations in genes on the X chromosome, one of the two sex chromosomes in each cell. Females have two X chromosomes, but a mutation in one of the two copies of the gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder. Since males only have one X chromosome, a mutation in the only copy of each cell's gene causes the disorder. While only a single copy of the mutation is enough to cause the disease in both males and females, males generally experience more severe symptoms than females. A characteristic trait of X-linked inheritance is that there is no male-to-male transmission; fathers cannot pass the X-linked traits to their sons since fathers only pass on their Y chromosome to their sons and their X chromosome to their daughters. As demonstrated in Figure 15, the sons of a male with an X-linked dominant disorder will not be affected, whereas 100% of his daughters will inherit the condition. The mother passes one of her X chromosomes to each child. Therefore, a woman with an X-linked dominant disorder has a 50% chance of having an affected daughter or son with each pregnancy (NLM, 2020e).

Figure 15

X-linked Dominant Disease Inheritance

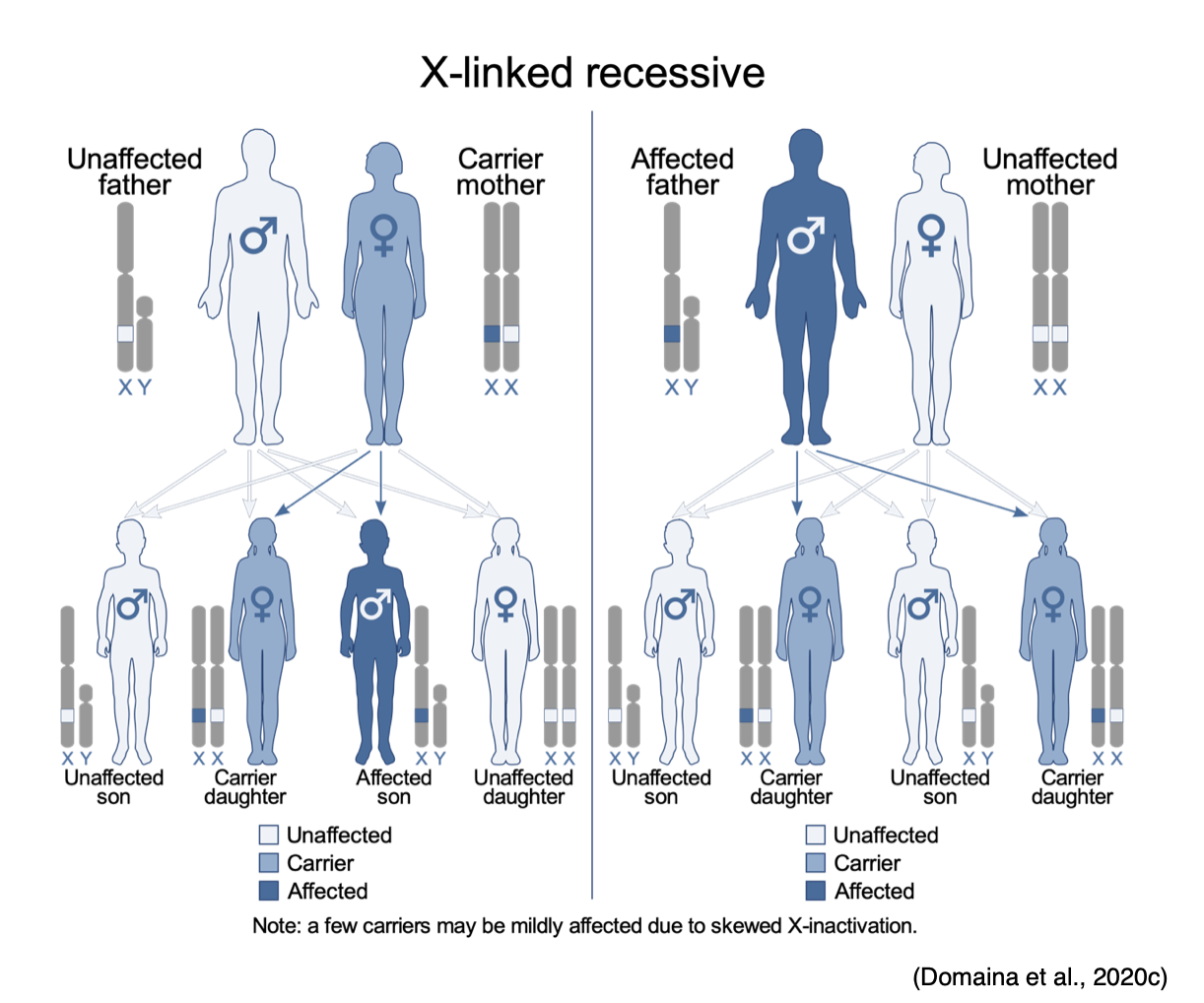

X-linked Recessive

X-linked recessive disorders are also caused by mutations in genes on the X chromosome. In males, one altered copy of the gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the condition; in females, a mutation would have to occur in both copies of the gene to cause the disorder. Since it is unlikely that females will acquire two altered copies of the gene, males are much more likely to be affected by X-linked recessive disorders than females. As demonstrated in Figure 16, the sons of a man with an X-linked recessive disorder will not be affected, while all of his daughters will carry one copy of the mutated gene. A woman with an X-linked recessive disorder has a 50% chance of having sons affected by the disorder, and a 50% chance of having daughters who carry one copy of the mutated gene (NLM, 2020e).

Figure 16

X-linked Recessive Disorder Inheritance

Factor V Leiden Thrombophilia (FVL)

A mutation in the FV gene causes FVL. FVL gene mutations cause factor V to be inactivated more slowly than normal, allowing the clotting process to remain active longer than usual. As a result, this increases the patient's risk for VTE (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center [GARD], 2017a). Considered the most common inherited form of thrombophilia, FVL affects approximately 3-8% of people with European ancestry. Although the condition increases the risk of VTE, only about 10% of affected individuals ever develop abnormal clots, with DVT and PE among the most common. FVL is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. The chance of developing abnormal blood clots depends on whether the individual has inherited one or two copies of the FVL mutation in each cell. Those who inherit two copies of the mutation (one from each parent) are at higher risk of developing a thrombus than those who inherit one copy of the mutation. The majority of individuals affected by the condition have one "normal" F5 gene and one with the factor V Leiden gene mutation. In the general population, 1 in 1,000 people per year (PPY) develop an abnormal blood clot. In patients with one copy of the FVL mutation, the risk of thrombus formation is 3 to 8 in 1,000 PPY, whereas two copies of the mutation heighten the risk to 80 in 1,000 PPY (NLM, 2020a).

Diagnosis of FVL can be suspected based on notable personal or family history of DVTs or PEs, particularly if occurring at a young age or with no identifiable risk factors. Testing for FVL is generally performed with the APC resistance assay, a screening test that evaluates the anticoagulant response to APC, or with targeted mutation analysis, which is a type of genetic test evaluating the F5 gene for the Leiden mutation. The targeted mutation analysis is considered the definitive test for diagnosis. It is generally recommended that patients who test positive by another means should subsequently undergo this test for confirmation and to distinguish heterozygotes from homozygotes (individuals with mutations in both copies of the gene). Treatment of FVL depends on the patient's underlying medical history and clinical findings. Patients who have had a prior DVT or PE are usually treated with anticoagulation therapy, such as warfarin (Coumadin) or a LMWH. Anticoagulation therapy is usually given for a finite period, ranging from three to six months. Lifelong anticoagulation is not recommended for the vast majority of patients with FVL unless additional risk factors warrant continued therapy. Patients who have never had a blood clot are not usually treated with anticoagulation therapy. Instead, prevention is centered on limiting other factors that will heighten the risk for blood clots. Temporary treatment with anticoagulation therapy may be advised for patients undergoing major surgeries (GARD, 2017a).

Prothrombin G20210A Mutation (Prothrombin Thrombophilia)

Prothrombin G20210A gene mutation is also referred to as prothrombin thrombophilia. Patients with this mutation produce excess amounts of prothrombin (FII), which leads to an abundance of thrombin in the circulation, thereby increasing the tendency to form VTE. Considered the second most common inherited form of thrombophilia, G20210A mutation is present in about 1 in 50 people in the Caucasian population and is more common in those of European ancestry. Prothrombin thrombophilia follows autosomal dominant inheritance, and the risk of developing a VTE is linked to the inheritance pattern of the condition. Heterozygous patients have a risk of 2 to 3 in 1,000 PPY, whereas those who are homozygous have risk of up to 20 in 1,000 PPY (NLM, 2020d). Testing for prothrombin G20210A is performed using a genetic test on a blood sample to see if there is a mutation in the prothrombin gene (GARD, 2017b).

Treatment for this condition depends on whether a blood clot has occurred and if there are additional risk factors. Asymptomatic patients who have never had a VTE are not usually treated with routine anticoagulation therapy (GARD, 2017b). Treatment is reserved for patients who have a VTE or are considered to be at risk of developing another VTE. Patients with current VTE should be treated with anticoagulation therapy for at least three to six months. Continuing therapy beyond this time frame depends on the circumstances surrounding thrombosis, if it was provoked or unprovoked, and the patient's risk factors (NLM, 2020d). Indefinite anticoagulation is generally advised for many patients with an unprovoked thromboembolic event, regardless of whether an inherited thrombophilia is identified (Bauer, 2020).

Deficiencies of Natural Proteins that Prevent Clotting

Antithrombin (AT) deficiency. Considered a rare condition affecting males and females in equal proportions, AT deficiency affects 1 in 3,000 to 1 in 5,000 individuals within the US. Only about 1% of patients who develop a VTE or PE have congenital AT deficiency. Caused by mutations in the SERPINC1 gene, patients with inherited deficiencies in AT have reduced levels of AT circulating within their blood. As previously mentioned, AT functions to limit blood clotting, serving as a natural anticoagulant. As the primary inhibitor of thrombin, those affected by AT deficiency are at a lifelong predisposition to developing VTEs. The majority of patients affected by inherited AT develop their first VTE before age 40 and usually manifest as a DVT or SVT, as arterial thrombosis is very rare in AT deficiency. About 40% of patients with AT deficiency develop a PE, which makes the condition particularly dangerous. AT deficiency follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, but unlike other conditions previously discussed, this one has variable clinical penetrance in heterozygotes. This means that not all patients who inherit one copy of the altered genetic mutation will be affected. Some may never endure a VTE event. Unfortunately, homozygotes with two copies of the altered gene are primarily seen in newborns who do not survive. Of note, AT deficiency is not always inherited. It can be acquired infrequently as a complication of another medical disorder, such as surgery, trauma, pregnancy, childbirth, metastatic cancer, and liver failure. This is important because while inherited AT deficiency increases the risk for blood clots, acquired AT deficiency usually does not (NBCA, n.d.a).

AT deficiency is diagnosed by a blood test that measures the level of antithrombin within the circulation, with lower than normal levels suggesting AT deficiency. The normal AT level is about 80 to 120%, whereas patients with inherited AT deficiency usually have lower levels (40 to 60%). Clinicians should be aware that warfarin (Coumadin) can increase AT levels. Therefore, a normal level in the setting of warfarin (Coumadin) therapy does not definitively rule out the presence of an AT deficiency (NBCA, n.d.a). According to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD, 2018), there is limited clinical trial data regarding the treatment of AT deficiency. There are differing opinions among clinicians regarding the treatment of the condition. While most agree that an individual with a definitive AT deficiency who has experienced a prior blood clot should be on indefinite anticoagulant therapy, the management of asymptomatic patients with AT deficiency is less clear. Clinical decisions are made based on the individual's coexisting risk factors and patient-provider shared decision making (NORD, 2018).

Deficiency in Protein C/S. Since protein C and protein S function as part of the body's innate anticoagulation mechanisms, if there is a deficiency in one or both of these proteins, or if either protein's functioning is impaired, clot formation can occur unregulated, leading to hypercoagulable states. Patients with deficiencies in either or both proteins are at increased risk for VTE events. These conditions are usually inherited, but can also be acquired (NLM, 2020b).

Protein C Deficiency. Inherited protein C deficiency is caused by a genetic mutation in the PROC gene. The degree of deficiency can be mild to severe. In milder forms of the condition, the patient may never endure a blood clot. Concerning inheritance patterns, protein C deficiency is primarily inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. There are two types of inherited protein C deficiencies, ranging from mild to severe. The severity of the deficiency is determined by the number of PROC gene mutations the patient has. In the rare instance that a patient inherits two mutated copies of the protein C gene (one from each parent), the disease can be very severe, heightening the risk for intracranial thromboembolism in infants and VTE during childhood. Type 1 deficiency is more common and is caused by a mutation in the PROC gene that causes an insufficient quantity of protein C. Type 2 deficiency is due to the reduced (or altered) function of the protein. Acquired protein C deficiency is usually due to an underlying condition such as infection, cancer, liver disease, or kidney disease, and resolves with treatment of the underlying disorder. It can also be caused by disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), sepsis, vitamin K deficiency, use of warfarin (Coumadin), or certain types of chemotherapy (NLM, 2020b).

Protein S Deficiency. Inherited protein S deficiency is caused by a genetic mutation in the PROC1 gene and is primarily inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Patients who inherit two mutation copies are at higher risk for developing a more severe form of thrombosis called purpura fulminans, which is a life-threatening condition involving severe clotting throughout the body. Purpura fulminans is characterized by blood spots, bruising, and discoloration of the skin from coagulation in the small blood vessels within the skin, which can lead to tissue necrosis. There are three types of inherited protein S deficiency; type 1 is due to insufficient quantity, type 2 results from abnormal functioning of protein S, and type 3 is due to decreased free protein S levels Acquired protein S deficiency is rare but can be due to liver disease or vitamin K deficiency. (AACC, 2019b).

Testing for protein C/S deficiencies is performed as two separate tests that are routinely done together. The tests measure the amount of each protein and evaluate whether they are properly performing their designated functions (AACC, 2019b). Treatment for protein C or S deficiency depends upon the severity of the condition. However, the majority of patients never develop an abnormal blood clot or require treatment. Patients who have endured a VTE are usually treated with anticoagulation therapy to prevent another blood clot from developing in the future. There is only one US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) approved treatment for the prevention and treatment of VTE and purpura fulminans secondary to severe congenital protein C deficiency. Protein C concentrate [Human] (Ceprotin) is an IV injection generated from human plasma that was first approved for use in 2007. Since it is human plasma, it carries a risk of transmission of infectious agents, particularly viruses, as well as bleeding events. The dose, administration frequency, and duration of treatment are dependent upon the severity of the protein C deficiency and the patient's age and plasma level of protein C. High doses of IV protein C concentrate (Ceprotin) help thin the blood and protect from blood clots. It can also be used as a preventative treatment against blood clots during surgery, pregnancy/delivery, prolonged immobility, or sepsis. However, it is not routinely used in clinical practice. According to the FDA prescribing guidelines, treatment must be initiated under the supervision of a hematology specialist experienced in replacement therapy with coagulation factors and inhibitors, and in a setting where monitoring of protein C activity is possible (FDA, 2007).

Hyperhomocysteinemia

Homocysteine is a type of amino acid, which is a chemical the body uses to generate proteins. Under physiologic conditions, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and folic acid break down homocysteine in the blood and transform it into substances the body needs, leaving minimal homocysteine circulating within the bloodstream. Hyperhomocysteinemia is characterized by increased levels of homocysteine in the blood, associated with a marked increase in the risk for VTE. Elevated homocysteine levels carry prothrombotic properties, causing vascular injury, platelet accumulation, and increased risk for forming occlusive thrombosis. Approximately 10% of primary episodes of VTE are due to elevated homocysteine levels (MedlinePlus, 2018a).