About this course:

The purpose of this module is to review the critical components of cancer prevention, risk reduction, and early detection, outlining the evidence-based American Cancer Society (ACS) cancer screening guidelines and recommendations, and the role of the advanced practice nurse.

Course preview

Objectives

Upon completion of this module, the learner should be able to:

- Describe the basic principles of cancer prevention and identify the distinguishing features of primary cancer prevention and risk reduction, as well as secondary cancer prevention.

- Review the American Cancer Society evidence-based cancer screening guidelines, classify the most common types of cancer screening tests, including screening modalities, indications, and discuss the benefits associated with cancer screening modalities.

- Discuss the limitations, risks, and adverse outcomes related to cancer screening modalities, as well as common barriers to screening.

- Describe the advanced practice nurse's role in cancer screening, patient education, awareness, and methods to convey accurate information to patients to promote informed shared decision-making regarding cancer screening.

Purpose

The purpose of this module is to review the critical components of cancer prevention, risk reduction, and early detection, outlining the evidence-based American Cancer Society (ACS) cancer screening guidelines and recommendations, and the role of the advanced practice nurse.

Background

Cancer is a cluster of malignant diseases characterized by abnormal cell growth, the ability to invade surrounding tissue and lymph nodes, and metastasize (spread) to distant locations within the body (Nettina, 2019). Cancer screening is an essential aspect of preventative medicine across primary care settings, as 30 to 50% of all cancer cases are preventable. Cancer risk assessment and appropriate screening can prevent disability and premature death associated with cancer (Loomans-Kropp & Umar, 2019). In the US, the burden of cancer is high. Cancer is currently cited as the leading cause of death for those under 65 years of age, and nearly 40% of men and women will be diagnosed with cancer at some point during their lifetime (Howlader et al., 2019). Despite these numbers, cancer is no longer considered a death sentence for a large percentage of those who are affected. Many cancers can be prevented, and others can be detected early in their development when they can be most effectively treated (Loomans-Kropp & Umar, 2019).

According to the American Cancer Society (ACS, 2019c), there are an estimated 16.9 million cancer survivors in the US, and this number is expected to rise to 26.1 million by 2040. Developments in early detection and screening practices have led to the birth of highly specialized techniques that can identify tissue changes indicative of cancerous precursors, as well as early-stage tumors. Premised on the biological and clinical understanding that a long incubation period is required for the development of malignant tumors, screening is recommended when there is substantial evidence that early diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic disease will reduce mortality or disease severity (Loomans-Kropp & Umar, 2019).

Treatment is more likely to be beneficial and useful when cancer is detected in its early stages, which is prior to the onset of symptoms. As with any intervention in medicine, screening is not without risks. Practitioners have a responsibility to ensure the benefits of cancer screening are understood, as well as the odds of being diagnosed with advanced cancer based on current knowledge and individual patient risk factors. In the setting of diagnosed cancer, continued surveillance and screening remain essential for the early detection of new and recurrent cancers (Jang et al., 2019). Primary prevention and secondary prevention are effective measures in decreasing mortality and morbidity from many types of cancers. The ACS recommends specific primary and secondary prevention measures to reduce an individual's risk of cancer death, which will be discussed throughout this module (ACS, 2018b).

What Causes Cancer?

While the definitive cause of cancer is not entirely understood, numerous factors are identified as increasing the risk for the disease and are generally distributed between two categories; modifiable and non-modifiable. Some theories propose that cancer may occur due to the spontaneous transformation of the cell, where no causative agent is identified, but the majority credit cancer development as a process resulting from cell damage induced by carcinogens, or outside influences. Carcinogens are substances, radiation, or exposures that can damage the genetic material (DNA) throughout one's lifetime, resulting in carcinogenesis, the formation of cancer (Itano, 2016). These factors may act simultaneously or in sequence to initiate and promote cancer growth (Yarbro et al., 2018). Some examples of preventable (or modifiable) carcinogens include tobacco smoking, alcohol abuse, tanning beds, diesel exhaust, and ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Age is the most outstanding nonmodifiable risk factor for cancer, as the incidence of cancer rises alongside age (Nettina, 2019). Inherited genetic mutations and immune conditions are additional nonmodifiable risk factors that require heightened patient and provider awareness to ensure proper cancer screening practices are implemented among this high-risk population. Other types of cancer risk factors include exposure to chemicals, viruses, poor nutrition, obesity, as well as sedentary lifestyle or physical inactivity (Yarbro et al., 2018). Poor nutrition can be defined by diets high in fats, processed foods, sugar and carbohydrates. The World Cancer Research Fund estimates that about 20% of all cancers diagnosed in the US are related to body fatness, physical inactivity, excess alcohol consumption, and/or poor nutrition; all of which could be prevented. Aside from the cancer screening and early detection guidelines, the ACS has also published guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention to guide the public on strategies to achieve optimal health and prevent cancer (ACS, 2017).

The Role of the Advanced Practice Nurse in Cancer Prevention and Early Detection

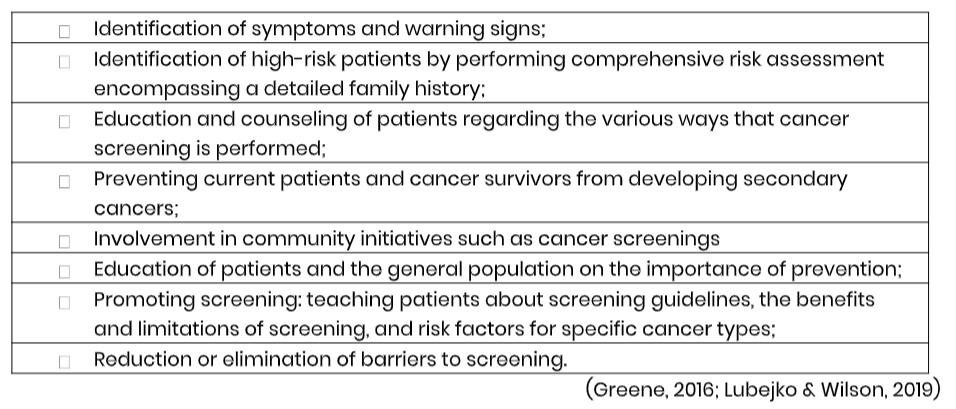

Advanced practice nurses (APRNs) are pivotal in cancer prevention and early detection efforts, serving as educators, medical liaisons, and disease experts. APRNs are positioned across health care settings, serving at the frontline of healthcare, and at the forefront of the fight against cancer. APRNs serve a critical role in addressing the negative health habits associated with cancer and the consequences of those behaviors. As outlined by the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP, 2019), the APRN performs a critical role in the assessment and reduction of risk factors before the disease occurs, as well as health promotion and counseling. APRNs are responsible for educating patients and their families on the importance of making specific lifestyle changes, as well as critical screening measures for the early detection of cancer. The APRN's scope of practice includes an emphasis on health promotion and disease prevention. Therefore, cancer prevention and early detection are clear responsibilities of the APRN, particularly those practicing in primary care and oncology specialties (AANP, 2019).

APRNs serve a role in administering cancer-preventing vaccinations, screening for cancer, performing cancer risk assessments, and evaluating patients who present with the warning signs concerning for cancer. APRNs provide long-term care to survivors of cancer who require close monitoring and surveillance throughout the remainder of their lifespan. Within the Oncology Nursing Society's Scope and Standards of Practice, advanced practice nurses are encouraged to ascertain educational preparation in the principles of cancer prevention and early detection. APRNs are encouraged to become skilled in their abilities to assess, evaluate,and interpret cancer risk assessments and recommend appropriate strategies related to cancer prevention and screening (Lubejko & Wilson, 2019).

...purchase below to continue the course

Recognizing the Warning Signs and Symptoms of Cancer

The nurse must educate patients on the early signs and symptoms that raise concern for a malignant process. The presenting signs and symptoms of cancer can vary widely depending on the type of cancer. A patient may be asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, or signs may be extremely vague and nonspecific, prolonging the time of symptom presentation until a definitive diagnosis is determined. Some cancers, such as leukemia and lymphoma, can exhibit a cluster of symptoms that suggest the diagnosis, such as constitutional symptoms of unexpected weight loss, night sweats, lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph nodes), and excessive fatigue. Unfortunately, many of the presenting symptoms of cancer are similar to the symptoms of various non-malignant illnesses, such as viruses or tick-borne diseases.

Some warning signs of cancer that should always warrant evaluation by a clinician include rectal bleeding, vaginal bleeding in postmenopausal women, a firm, fixed, or abnormal new lump in the breast, abdominal bloating or distension that does not resolve, unexplained weight loss, or productive cough with hemoptysis (blood-streaked sputum or coughing up blood clots). Most lung cancers do not cause any symptoms until they have spread, but some people with early lung cancer may have symptoms such as a persistent cough that does not go away or gets worse, coughing up blood or rust-colored sputum, chest pain that is often worse with deep breathing or coughing, shortness of breath, and recurrent infections, such as bronchitis and pneumonia (ACS, 2019d). Cancer may present in many other ways, so a thorough history taking and physical assessment are critical (Yarbro et al., 2018).

Cancer-Directed Physical Examination

A cancer-directed physical examination should include a thorough evaluation of the oral cavity. The mucous membranes and tongue should be inspected for color and integrity, as well as the presence of lesions and plaques. The tongue should be palpated for masses and tenderness. Examination of the breasts should include assessment for the presence of any firm, fixed masses or axillary lymphadenopathy. Blood or purulent discharge expelled from the nipple is a severe warning sign that warrants immediate evaluation. Skin changes such as erythema, retraction, thickening, or dimpling of the skin on the breast so that it looks like an orange peel (peau d’orange), or any open wounds or lesions that arise spontaneously all warrant further evaluation (Yarbro et al., 2018).

Suspicious warning signs identified on physical exam may include:

- Oral Cavity: White lesions (leukoplakia) or red lesions (erythroplakia), growth or ulceration in the mouth, firm or fixed nodule anywhere in the oral cavity;

- Nasopharynx: Nosebleed, permanently blocked nose, deafness, enlarged lymph nodes in the upper part of the neck;

- Larynx: Persistent hoarseness of voice without identifiable cause;

- Breast: Lump in the breast, asymmetry, skin retraction, recent nipple retraction, blood- stained nipple discharge, eczematous changes in areola, peau d’orange appearance of the skin;

- Lung: decreased breath sounds, chest pain/pleuritic pain, persistent cough, hemoptysis;

- Stomach: Upper abdominal pain, recent onset of indigestion, unexplained/unintentional weight loss;

- Colon and rectum: Change in bowel habits, thin stools, unexplained weight loss, anemia, blood in the stool;

- Skin: a brown or dark-colored lesion that is growing with irregular borders or areas of patchy color that may itch or bleed, keratosis (lesion or sore on the skin that does not heal), primarily on sun-exposed areas of the body;

- Bladder: Dysuria (pain with urination), frequent and uneasy urination, blood in the urine;

- Cervix: Post-coital bleeding, excessive vaginal discharge, cervix that is easily friable;

- Prostate: persistent difficulty with urination, frequent nocturnal urination;

- Testicular: Swelling of one testicle (asymmetry), lump in the testicle (Nettina, 2019).

Table 1

Responsibilities of the APRN in Cancer Prevention and Early Detection

Performing a Cancer Risk Assessment

A comprehensive risk assessment is a vital first step for cancer prevention and early detection. A cancer risk assessment is an individualized evaluation of a patient's risk for cancer based on a variety of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors; it begins with a detailed history (Greene, 2016). The components of a cancer risk assessment include thorough past medical, surgical, and social history, as well as the documentation of any age-appropriate screening tests previously performed (or lack thereof). The patient's family history is a critical component of a comprehensive cancer risk assessment and includes at least a three- generation pedigree, particularly if a hereditary cancer syndrome is suspected. This helps identify key features of familial cancers and genetic syndromes that require heightened surveillance, screening, and at times, prophylactic interventions. Medication history (such as hormone use), dietary history, level of physical activity, environmental exposures, history of tobacco and alcohol use, and other lifestyle choices also are important factors to assess when determining cancer risk (Nettina, 2019).

Cancer Risk Assessment Tools

Multiple cancer risk assessment tools and models are available to help estimate overall cancer risk and select interventions to reduce that risk. The models also help assist with conveying this information and counseling patients. The models are intended for use as an adjunct to an individualized, comprehensive cancer risk assessment.

- Gail model - the most commonly used comprehensive breast cancer risk assessment tool, it is used to estimate a woman's five-year risk and overall lifetime risk for breast cancer.

- MMRpro model -evaluates for hereditary colon cancer risk.

- The National Cancer Institute (NCI) has several cancer risk assessment tools available online at cancer.gov, most prominently those for breast and colon cancer risk assessment (Smith et al., 2019).

Primary Prevention and Risk Reduction

Primary cancer prevention consists of interventions aimed at keeping the carcinogenic process from beginning. A substantial proportion of cancers can be prevented through primary risk reduction, which involves minimizing harmful exposures and reducing or omitting unhealthy lifestyle behaviors. ACS (2018b) researchers have determined that approximately 42% of newly diagnosed cancers in the United States are potentially avoidable, as they are directly correlated with tobacco use, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and other modifiable behaviors. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2019a), primary cancer prevention offers the most cost-effective long-term strategy for the control of cancer. Many cancers are linked to tobacco use, unhealthy diet, lifestyle behaviors, and specific types of infections or viruses, thereby heightening the significance of evidence-based cancer prevention practices. The ultimate goal of primary cancer prevention is to reduce cancer risk through lifestyle behavioral interventions (ACS, 2018b).

Tobacco Use

Tobacco use remains the single most preventable risk factor for cancer mortality worldwide, as all cancer deaths related to tobacco are entirely avoidable. Tobacco smoke has more than 7,000 chemicals, at least 250 of which are known to be harmful, and more than 50 are known to cause cancer. Tobacco harms every organ in the body and is associated with at least 15 types of cancers, including cancers of the lung, bladder, head and neck, kidney, cervix, liver, and pancreas (ACS, 2019c). Tobacco is attributed to more than 480,000 deaths annually, with 42,000 deaths from secondhand smoke (Nettina, 2019).

According to the NCI (2017), people who stop smoking experience immediate and long-term health benefits, including reducing their risk of developing lung cancer or of having lung cancer recur. Within minutes of smoking the last cigarette, the body begins to restore itself, and within a few hours, the level of carbon monoxide in the blood begins to decline. In only a few days, the body's heart rate and blood pressure begin to normalize, and within a few weeks, circulation is improved. Within several months of quitting, there is a substantial improvement in lung function, with a decline in coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, and sputum production. Within a few years of quitting, the risks of cancer, heart disease, and other chronic diseases are lower than if they had continued to smoke. Within five years of quitting, the risk of death from lung cancer decreases by 21%. Quitting smoking lowers the risk of developing cancer and dying from cancer. It also improves the prognosis of cancer patients, as quitting smoking at the time of diagnosis may reduce the risk of dying up 30 to 40% (NCI, 2017). The ACS first released a position statement on e-cigarettes in February 2018, emphasizing that no youth or young adult should begin using any tobacco product, including e-cigarettes (ACS, 2017).

ACS Recommendations on Tobacco Use and Cancer Prevention

- All tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, pose serious risks and health consequences.

- All adults who smoke conventional cigarettes or other combustible (burned) tobacco products should be advised to quit smoking at the earliest opportunity and stay tobacco-free.

- E-cigarettes should not be used to quit smoking.

- Clinicians should help patients seek cessation support and, when appropriate, use FDA-approved medications, including nicotine replacement therapies (NRT) and/or recommended oral medications, preferably combined with individual or group behavioral counseling, which significantly increases the likelihood of success.

- ACS offers cessation support to all tobacco users by calling 1-800-QUIT-NOW or 1-800- ACS-2345 (ACS, 2017).

Alcohol

Excess alcohol intake and alcohol abuse increases the risk for several types of cancer. Alcohol use has been linked with cancers of the head, neck, throat, oropharynx, esophagus, liver, colon/rectum, breast, pancreas, and stomach. The more alcohol that is consumed over time, the higher the risk for cancer development. Further, drinking alcohol and using tobacco together raises the risk of these cancers more than drinking or smoking alone. Alcohol behaves as an irritant within the mouth and throat, allowing harmful chemicals such as tobacco smoke, to enter the cells lining the digestive tract. It can lead to inflammation and scarring of the liver, reducing the body's ability to break down harmful chemicals and other exposures. Alcohol reduces the body's ability to absorb certain nutrients, especially folate (folic acid). Folate is a water-soluble B complex vitamin found within food that is essential for red blood cell production and maturation. The human body relies on the dietary intake of folate, which is absorbed within the small intestine and transported to the liver where it is stored. Many cellular processes in the body require folate to function properly. Therefore, folate deficiencies significantly contribute to disruptions in cellular development, inducing a number of sequela at the cellular level, contributing to cancer (McCance & Heuther, 2014).

ACS Recommendations on Alcohol and Cancer Prevention

1. Men should limit alcohol intake to no more than two drinks per day.

2. Women should limit alcohol to one drink per day.

- A drink of alcohol is defined as 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine, or 1½ ounces of 80-proof distilled spirits (hard liquor).

3. People who should not drink alcohol at all:

- Children and teens;

- People of any age who cannot limit their drinking or who have a family history of alcoholism;

- Pregnant women or women who may become pregnant;

- People who drive or operate machinery;

- People who take part in other activities that require attention, skill, or coordination;

- People taking any medications (prescription or over-the-counter) that interact with alcohol (ACS, 2017).

Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Weight Management

Excess body fat and obesity have a major impact on cancer development, progression, and cancer recurrence. Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher and excess fat accumulation in relation to height. There is a well-cited association between being overweight or obese and a heightened risk of several types of cancers, including, breast, colon/rectum, endometrial (uterine), esophageal, kidney, and pancreatic (ACS, 2017). One key example of the detrimental relationship between cancer and obesity is endometrial cancer. Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy, with an estimated 61,880 new cases to be diagnosed in the United States in 2019, and 12,160 predicted deaths (Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program [SEER], 2018). Historically recognized as a disease of postmenopausal women, it has a strong association with obesity. Endometrial cancer is now becoming much more prevalent in the younger, premenopausal population, ranking as the fourth most common cancer among women in the United States. The increased incidence is mostly attributed to the global obesity epidemic, and the resulting metabolic disorder; obesity is cited as being responsible for up to 81% of all endometrial cancers diagnosed worldwide. The underlying etiology is premised on an exposure-response relationship between excess fat tissue and endometrial cancer risk, which is driven by an overproduction of estrogen (hyperestrogenism) carried in adipose tissue, insulin resistance, increased bioavailability of steroid hormones, and inflammation (Moore & Brewer, 2017). These processes generate a metabolic state that drives tumorigenesis (Papatla et al., 2016). For those already diagnosed with endometrial cancer, obesity not only leads to poorer long-term health outcomes, but it is also found to impact the treatment course negatively. Obese women with endometrial cancer are more likely to die from other obesity-related diseases than endometrial cancer (Jenabi & Poorolajal, 2015).

ACS Recommendations on Nutrition, Physical Activity, Weight Management and Cancer Prevention

1. Achieve and maintain a healthy weight throughout the lifespan:

- Maintain a BMI of 18.5 to 24.9;

- Be as lean as possible throughout life without being underweight;

- Avoid excess weight gain at all ages;

- Get regular physical activity and limit the intake of high calorie foods and drinks.

2. Be physically active:

- Adults should get at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity each week (or a combination), preferably spread throughout the week;

- Children and teens should get at least one hour of moderate or vigorous- intensity activity each day, with vigorous activity on at least three days each week;

- Limit sedentary behavior such as sitting, lying down, watching TV, and other forms of screen-based entertainment;

- Perform some physical activity above usual activities on a daily basis.

3. Eat a healthy diet, with an emphasis on plant foods:

- Calorie and portion control;

- Limit the quantity of processed meat and red meat consumed;

- Consume at least 2½ cups of vegetables and fruits each day;

- Choose whole grains instead of refined grain products (ACS, 2017).

Sun Safety

People who get a lot of exposure to UV rays are at higher risk for skin cancer, as skin cancers are primarily due to excessive UV radiation exposure. The majority of UV exposure comes from the sun, but it can also come from indoor tanning beds and sun lamps. Skin prevention strategies focus on the application of proper sunscreen, lightweight clothing, and hats to shield oneself from direct exposure, reducing sunlight exposure during peak hours of the day when the ultraviolet rays are the strongest, and avoiding tanning beds altogether (Polovich et al., 2014). The best way to detect skin cancer early is to be aware of new or changing skin growths, particularly those that look unusual. Diagnosis is usually suspected in older, fair-skinned patients who present with scaly, indurated lesions on sun-exposed areas of the head and neck (ACS, 2019c). Specific risk factors associated with increased environmental or artificial UV exposure include:

- Long term, intense sun exposure lacking adequate use of sunblock and other sun safety precautions;

- Northern European ethnic origin;

- People with fair skin, blond or red hair, and light-colored eyes;

- A tendency to burn rather than tan;

- Proximity to the equator;

- History of blistering sunburns in childhood and adolescence;

- Use of indoor tanning beds;

- People with a weakened immune system (immunocompromised state), including having had an organ transplant;

- Exposure to therapeutic ionizing radiation;

- HIV seropositive;

- Specific genetic syndromes (ACS, 2018b, 2019c).

While many researchers and clinicians argue that skin cancer screening with a total body skin examination is one of the safest, practical, and most cost-effective screening tests in medicine, there currently remains no national consensus regarding its benefit or implementation (ACS, 2018b).

ACS Recommendations on UV Exposure and Cancer Prevention

- Perform monthly skin self-examinations for the detection of early skin cancer.

- Any new lesion or a progressive change in a lesion's appearance (size, shape, or color change) should be evaluated promptly by a clinician

- Take steps to limit exposure to UV rays:

- Seek shade and limit direct sunlight exposure, especially between the hours of 10 am and 4 pm, when UV light is the strongest.

- Implement the catchphrase, 'Slip, slop, slap, and wrap!' (slip on a shirt, slop on sunscreen, slap on a hat, and wrap on sunglasses)

- Long-sleeved shirts, long pants, or long skirts cover the most skin and are the most protective. Dark-colored clothing provides more protection than light-colored clothing.

- Choose a sunscreen with broad-spectrum protection against both UVA and UVB rays and with a sun protection factor (SPF) value of 30 or higher.

- No sunscreen provides 100% protection.

- Wear a hat with at least a 2- to 3-inch brim to shield the sun.

- Wear UV-blocking sunglasses to protect the eyes and skin surrounding the eyes.

- Avoid tanning beds and sun lamps (ACS, 2017; ACS 2018b).

Refer to NursingCE.com module entitled, 'Skin Cancer and Prevention' for a 2-credit course on this topic.

Infections, Viruses, and Immunizations

Certain infections and viruses are associated with an increased risk of certain forms of cancer, such as hepatitis B or C and hepatocellular cancer (Nettina, 2019). Cancers related to the human papillomavirus (HPV) can be prevented through behavioral and lifestyle changes, as well as through vaccination (Nettina, 2019). HPV is thought to cause more than 90% of cervical cancers, and each year, more than 33,000 people in the US are diagnosed with cancers caused by HPV (ACS, 2019e). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2019), 80% of people will get an HPV infection in their lifetime, and approximately 14 million Americans become infected with HPV each year. HPV can cause cancers of the cervix, vagina, vulva, throat, tongue, and tonsils. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved HPV vaccination, Gardasil9, can protect against over 90% of HPV cancers and genital warts (CDC, 2019).

ACS Recommendations on HPV Vaccination and Cancer Prevention

- Routine HPV vaccination for girls and boys should be started at age 11 or 12, but the vaccination series may be started as early as age 9.

- The HPV vaccination is recommended for females 13 to 26 years old and for males 13 to 21 years old who have not started or completed the vaccine series.

- Males 22 to 26 years old may also be vaccinated, but the vaccination within this age range is less effective in lowering cancer risk.

- The HPV vaccination is also recommended through age 26 for men who have sex with men and for people with a weakened immune system, including those with HIV infection (ACS, 2019e).

Refer to NursingCE.com module entitled, "Human Papillomavirus (HPV)” for a 2-credit course on this topic.

Secondary Cancer Prevention

Secondary cancer prevention involves partaking in activities such as screenings and testing to identify those at high-risk who require increased surveillance as compared to the general population (Yarbro et al., 2018). These measures can prevent cancer through the identification of precancerous lesions and by taking appropriate action before the cells develop into invasive cancer. Early detection is based on the concept that the sooner the cancer is detected, the more effective the treatment is likely to be (ACS, 2018b). It greatly increases the chances of successful treatment and the potential for a cure. Millions of cancer patients could be saved from premature death and suffering if they had timely access to early detection and treatment (WHO, 2019b).

Early detection strives to improve overall outcomes and patient survival. There are two main components of early detection: early diagnosis and screening. The aim of early diagnosis is to find cancer when it is localized to the organ of origin and before it invades the surrounding tissues or spreads to distant organs. Early diagnosis involves educating patients to promote awareness of the early signs and symptoms, leading to consultation with a health provider, who then promptly refers the patient for confirmation of diagnosis and treatment. Screening of asymptomatic and healthy individuals aims to detect precancerous lesions or an early stage of cancer, and to arrange a referral for diagnosis and treatment. Screening allows for the early identification of cancer before the onset of symptoms. Examples of cancer screening tests including colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), mammography, Papanicolaou test (Pap smear), prostate-specific antigen (PSA), and digital rectal exam (DRE) (ACS, 2018b).

ACS guidelines recommend cancer screening programs with low-dose spiral computed tomography (CT) scans to detect curable stage I lung cancer in patients who meet the designated criteria. The decision to perform a routine screening tests should be based on whether the test is adequate to detect a potentially curable cancer in an otherwise asymptomatic person and is also cost-effective. Screening decisions should be based on an individual's age, sex, family history of cancer, ethnic group or race, previous iatrogenic factors (prior radiation therapy), and history of exposure to environmental carcinogens (Yarbro et al., 2018).

Cancer Screening Guidelines

There are various sets of cancer screening guidelines put forth by credible organizations and grounded in clinical research, evidence, and expert consensus. While there are some variations between the sets of guidelines, they are relatively consistent in their recommendations. The American Cancer Society is one of the most widely utilized, comprehensive, evidence-based resources for cancer care; they publish an annual report that summarizes recommendations for cancer screening (ACS, 2018b; Smith et al., 2019).

Breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in the US and a leading cause of premature death and morbidity. The ACS estimates that in 2019, there will be 268,600 cases of invasive breast cancer and 41,760 deaths (Smith et al., 2019). Breast cancers identified during screening exams are more likely to be small and still confined to the breast. The size of breast cancer and how far it has spread are some of the most important factors in predicting the patient’s prognosis, as the size of cancer at the time of diagnosis is directly related to mortality. Breast cancer screening is performed through mammography, which is an x-ray of the breast. Screening mammograms have the ability to detect cancers before they grow large enough to become palpable lumps. Dense breast tissue is an independent risk factor for the development of breast cancer, relative risk 2-6x compared with less-dense breasts. Starting screening mammography at age 40 saves the most lives and saves the most years of life, and annual screening saves more lives than every other year (biennial) (ACS, 2019b).

Annual mammography screening in premenopausal women is associated with a significantly decreased risk of identifying advanced breast cancer compared with screening performed every other year. Postmenopausal women do not have similar benefits related to yearly screening unless they are currently receiving hormone treatment for menopause; therefore, women 55 years or older can receive screening every other year or yearly, depending on patient preference. The age to stop screening is not yet identified, but continued screening may be beneficial in certain women 75 years or older, depending on their mortality risk, comorbidities, overall health, and performance status. Patients should be advised not to schedule their mammogram the week prior to or during their menstrual cycle as the breasts may be more tender and swollen during these periods. Patients should also be instructed on the importance of avoiding deodorants, perfumes, or powders (CDC, 2018). All women should be familiar with the known benefits, limitations, and potential harms linked to breast cancer screening. Women should check their breasts regularly to know how their breasts normally look and feel. They should be counseled to report any breast changes to a health care provider right away (ACS, 2019b; Smith et al., 2019).

Summary of Breast Cancer Screening Recommendations

Average-Risk Women

- Women aged 40 to 44 should have the opportunity to begin annual screening with mammography;

- In women aged 45 to 54, annual mammography should be routinely performed;

- Women aged 55 or older should transition to biennial screening (screening every two years) or may continue screening annually;

- Women should continue screening mammography as long as their overall health is good and they have a life expectancy of 10 years or longer;

- Some women who are at high-risk for breast cancer due to family history, a genetic predisposition, or certain other factors, should be screened with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) along with mammograms (ACS, 2018b; ACS, 2019b; Smith et al., 2019).

High-Risk Women

Women who are known or likely carriers of a breast cancer gene (BRCA) mutation and other rare high‐risk genetic syndromes or who have been treated with radiation to the chest for Hodgkin disease or other cancers are considered at increased risk. Annual screening mammography and MRI starting at age 30 years are recommended for women with a known BRCA mutation, women who are untested but have a first‐degree relative with a BRCA mutation, or women with an approximately 20% to 25% or greater lifetime risk of breast cancer based upon specialized breast cancer risk‐estimation models capable of pedigree analysis of first‐degree and second‐degree relatives on both the maternal and paternal sides. Annual MRI and mammography are also recommended for women who were treated for Hodgkin disease with radiation to the chest between ages 10 and 30 years (Smith et al., 2019).

Lung Cancer

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer affecting both men and women and the leading cause of cancer deaths. Each year, more people die of lung cancer than of colon, breast, and prostate cancers combined. The ACS estimates there will be approximately 228,150 new cases of lung cancer and 142,670 deaths from lung cancer in 2019 (ACS, 2019d). Risk factors for lung cancer include tobacco use, secondhand smoke, and harmful chemical or radioactive exposures. Radon is a radioactive gas produced by the breakdown of uranium in soil and rocks. It is an odorless and tasteless gas and is the second leading cause of lung cancer in the US, and the leading cause among non-smokers. Additional carcinogens that can increase lung cancer risk include diesel exhaust, asbestos, inhaled chemicals such as arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, silica, vinyl chloride, nickel compounds, chromium compounds, coal products, mustard gas, and chloromethyl ethers. Prior radiation therapy to the chest for other cancers also increases the risk of lung cancer development. This is common in breast cancer patients as many receive chest wall radiation following a mastectomy (ACS, 2019d).

Summary of Lung Cancer Screening Recommendations

Lung cancer screening is advised for those who are current or former smokers, as these individuals are at higher risk for lung cancer. The ACS recommends annual lung cancer screening with low-dose CT scan (LDCT) for people who meet the following criteria:

- Adults aged 55 to 74 years and in reasonably good health, and

- Currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years, and

- Have at least a 30-pack-year smoking history, and

- Receive smoking cessation counseling if they are current smokers, and

- Have been involved in informed/shared decision making about the benefits, limitations, and harms of screening with LDCT scans, and

- Have access to a high-volume, high-quality lung cancer screening and treatment center (ACS, 2019a).

A pack-year is defined a one pack of cigarettes per day per year. One pack of cigarettes per day for 30 years or two packs per day for 15 years would both be 30 pack-years. Clinicians with access to high-volume, high-quality lung cancer screening and treatment centers should initiate an informed and shared decision-making discussion with patients who meet the above criteria regarding the potential benefits, limitations, and harms associated with screening for lung cancer with LDCT scans. Smoking cessation counseling remains a high priority for clinical attention in discussions with current smokers, who should be informed of their ongoing risk of lung cancer if they do not stop smoking. Screening should not be viewed as an alternative to smoking cessation and current smokers should be referred to smoking cessation programs (Smith et al., 2019).

Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer diagnosed among adults and the second leading cause of death from cancer in the US (Wolf et al., 2018). In 2019, the ACS estimates that 145,600 new cases of CRC will be diagnosed in women and men, and 51,020 women and men will die from it (Smith et al., 2019). CRC screening can detect cancer early when the tumor is small, localized, and easier to treat. When CRC is found at an early stage before it has spread, the 5-year relative survival rate is about 90%. Regular screenings at defined intervals can prevent CRC from developing, as a cancerous polyp can take 10 to 15 years to progress into cancer. Screening allows for the prevention of CRC through the removal of abnormal, suspicious, or precancerous polyps before they have the ability to ever develop into cancer (ACS, 2018a). Common symptoms that should raise suspicion for CRC may include the following: gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal upset, unexplained weight loss, or a change in stool habits (Wolf et al., 2018).

Increased or High-risk for CRC

Those who are at increased or high risk of CRC generally need to start screening before the age of 45. They often require more frequent screening and specific testing. The ACS defines individuals at high-risk to include those with one or more of the following:

- A strong family history of colorectal cancer

- A personal history of colorectal cancer or certain types of polyps

- A personal history of inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease)

- A known family history of a hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or Lynch syndrome (also known as hereditary non- polyposis colon cancer or HNPCC)

- A personal history of radiation to the abdomen (belly) or pelvic area to treat a prior cancer (ACS, 2018a).

Individuals at average risk for CRC are defined by the absence of the above risk factors. The guidelines for those at increased or high-risk for CRC vary based on the individual patient. While the ACS does not put forth screening guidelines specifically for people in these risk categories, other professional organizations, such as the US Task Force on Colorectal Cancer (USPSTF) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) offer more complex guidelines which must be applied to each patient based on his or her individual risk factors (ACS, 2018a).

Screening Modalities for CRC

There are multiple options for CRC screening, all of which are associated with a significant reduction in CRC incidence through the early detection and removal of adenomatous polyps and precancerous lesions. There are several test options for colorectal cancer screening which include:

1. Stool-based tests:

- Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) performed every year;

- High‐sensitivity guaiac‐based fecal occult blood test (HSgFOBT) performed every year;

- Multitarget stool DNA test (mt‐sDNA), performed every three years;

2. Visual (structural) exams of the colon and rectum

- Colonoscopy performed every ten years;

- Computed tomography colonography (virtual colonoscopy) performed every five years;

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy (FSIG) performed every five years (Smith et al., 2019; Wolf et al., 2018).

Summary of Colorectal Cancer Screening Recommendations

- Average-risk adults aged 45 years and older should undergo regular CRC screening with either a high-sensitivity stool-based test or a visual exam, based on patient preference and test availability.

- Average‐risk adults in good health with a life expectancy of more than ten years should continue CRC screening through the age of 75.

- Clinicians should individualize CRC screening decisions for individuals aged 76 through 85 years based on patient preferences, life expectancy, overall health and performance status, and prior screening history.

- Clinicians should discourage individuals older than 85 years from continuing CRC screening.

- All positive results on non-colonoscopy screening tests must be followed up with a timely colonoscopy (Wolf et al., 2018).

Cervical Cancer

The ACS estimates that 13,170 women will be diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer, and 4,250 women will die from the disease in 2019. Cervical cancer screening with the use of high‐quality screening with cytology (Pap testing) has successfully decreased cervical cancer incidence and mortality. Pap testing has markedly reduced mortality from squamous cell cervical cancer, which comprises 80% to 90% of cervical cancers (Smith et al., 2019).

Summary of Cervical Cancer Screening Recommendations

- Cervical cancer screening should begin at age 21.

o Women under age 21 should not be screened, regardless of the age of sexual initiation.

- Women aged 21 through 29 should have a screening test performed every three years (Pap test).

o HPV co-testing should not be performed routinely in this age group.

o HPV co-testing should only be performed if needed after an abnormal Pap test result.

- Women aged 30 to 65 should be screened every five years with both the HPV test and the Pap test (preferred recommendation), or every three years with a Pap test alone.

- Women aged 65 and older who have had at least three consecutive negative Pap tests or at least two consecutive negative HPV and Pap tests within the last ten years, with the most recent test occurring over the previous five years, should stop cervical cancer screening. Once testing is stopped, it should not be resumed again.

- Women with a history of a precancerous lesion should continue to be tested for at least 20 years after that diagnosis, even if testing goes past the age of 65.

- Women who have had a total hysterectomy (removal of the uterus and cervix) for reasons not related to cervical cancer and who have no history of cervical cancer or pre-cancer should not be tested for cervical cancer.

- All women who have been vaccinated against HPV should still follow the screening recommendations for their age group (Smith et al., 2019).

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in men in the US, with an estimated 174,650 new cases and 31,620 deaths predicted in 2019 (Smith et al., 2019). There has been controversy over prostate cancer screening regarding its risks and benefits for several decades. There are two modalities that are used for prostate cancer screening, the prostate‐specific antigen test (PSA) and the digital rectal examination (DRE) (Kappen et al., 2019). Prostate cancer screening may be associated with reduce mortality from prostate cancer, but the evidence remains conflicting, and experts disagree about the value of screening (Smith et al., 2019). The major shortcoming of prostate cancer screening is the impact and value of the information received. For men whose prostate cancer is detected by screening, it is impossible to predict which men are likely to benefit from treatment. Some men who are treated may avoid death and disability from prostate cancer, whereas others who are treated would have died of unrelated causes before their cancer became serious enough to spread, affect their health, or reduce the quality and longevity of their lives. There is an extensive literature base surrounding the potential overtreatment and overdiagnosis of prostate cancer due to PSA screenings (Kappen et al., 2019)

Currently, the ACS advises that prostate cancer screening should not occur without an informed decision-making process between the healthcare provider and the patient, reviewing the pros and cons of the screening test. Men who have at least a 10-year life expectancy should have the opportunity to make an informed decision about undergoing prostate cancer screening with serum PSA, with or without DRE. Men who fall into higher risk categories include African Americans and those with a first-degree family member (father or brother) who was diagnosed with prostate cancer prior to age 65. Additional factors that increase the risk of prostate cancer include increasing age, abnormal DRE, and high age- specific PSA level test. Research is still debating on the value and best use of the PSA and DRE (Smith et al., 2019).

Summary of Prostate Cancer Screening Recommendations

- At age 50, average-risk men should have an informed/shared decision-making conversation with their health care provider about the pros and cons of prostate cancer screening.

- African Americans and men who have a first-degree relative who was diagnosed with prostate cancer prior to age 65 are at higher risk and should have this informed/shared decision-making conversation starting at age 45.

- Men at highest risk (those with multiple first-degree relatives diagnosed with prostate cancer prior to age 65) should receive this information at age 40.

- Asymptomatic men who have a less than 10-year life expectancy based on age and health status should not be offered prostate cancer screening.

- For patients who decide to be tested, the ACS recommends the following:

- Men aged 50 and older may opt to undergo PSA testing with or without DRE (DRE is recommended along with PSA for men with hypogonadism because of reduced sensitivity of PSA).

- The frequency of performing the test depends on the results, as well as patient and provider preference

o PSA less than 2.5 ng/mL: screening intervals can be extended to every two years;

o PSA of 2.5 ng/mL or higher: screening should be conducted yearly;

o PSA of 4.0 ng/mL or higher: referral for further evaluation or biopsy;

o For men in higher-risk categories with PSA levels between 2.5 and 4.0 ng/mL, an individualized risk assessment should be used for making referral recommendations (ACS, 2018b; Smith et al., 2019).

Endometrial Cancer

In 2019, the ACS estimates that 61,880 women will be diagnosed with and 12,160 women will die from endometrial (uterine) cancer. In 2001, the ACS concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend screening for endometrial cancer in women at average risk, and their assessment remains unchanged today. The ACS recommends that at the time of menopause, women should be informed about risks and symptoms of endometrial cancer and strongly encouraged to report any unexpected vaginal bleeding or spotting to their healthcare provider. Endometrial biopsy is the standard for determining the status of the endometrium and is advised if there are symptoms raising a concern or suspicious for the disease (Smith et al., 2019).

Risks and Limitations of Cancer Screening

Despite the notable benefits of cancer screening, no screening test is perfect, as they are not without risks and limitations. While there have been tremendous advancements regarding the early detection and screening processes for several types of cancer, there are not published guidelines and screening recommendations available for every type of cancer. For example, ovarian cancer is one of the deadliest cancers, yet no organization recommends routine screening for ovarian cancer in average‐risk women. Less than one-half of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer survive longer than five years, and only 15% of all patients are diagnosed with localized disease. In 2019, approximately 22,530 women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer and 13,980 will die from the disease. Screening and diagnostic methods for ovarian cancer include pelvic examination, cancer antigen 125 (CA 125) blood level tumor marker, and transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) (Smith et al., 2019). Due to limitations in ovarian cancer screening modalities and lack of evidence to suggest the benefit of screening average-risk women, these modalities are generally reserved for women of higher risk, such as those with a hereditary genetic predisposition or strong family history (ACS, 2018b).

APRNs must engage in informed and shared decision-making with patients regarding the benefits and limitations of cancer screening modalities. These discussions help patients clarify their values and decide if they are willing to accept the risks and costs associated with screening. All types of cancer screening pose a relatively high likelihood of the need for further tests. Some tests have higher risks for complications, whereas others are safer and pose fewer risks. Regardless of the patient's preference, the APRN has a responsibility to ensure the patient is educated on the risk and benefit ratio to make an informed decision (Greene, 2016).

The common risks of cancer screening include false-positive test results, false-negative test results, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment. Detecting cancer may not always improve the patient's health or survival. Screening can also lead to overdiagnosis and overtreatment. The widespread use of mammography and prostate cancer screening are primary examples of the potential harms stemming from the detection of indolent lesions and subsequent overtreatment. Further, this contributes to increased and unnecessary healthcare spending and stimulates patient anxiety. False-negative test results are a limitation of cancer screening, in which the screening test misses, or fails to detect, cancer. LDCT scans do not detect all lung cancers, and not all patients who have lung cancer detected by LDCT will avoid death from lung cancer. Mammograms may miss some cancers, which may delay finding cancer and getting treatment (ACS, 2018b).

False-positive test results occur when something found on screening looks like cancer, but it turns out to be benign. This can lead to the need for additional testing, which can be expensive, invasive, time-consuming, and may stimulate additional anxiety. In some instances, an invasive procedure is needed to determine whether or not an abnormality is a cancer or some non‐cancerous or non‐related incidental finding. Any invasive procedure poses the risk of minor and major complications. Testing can lead to overdiagnosis, which occurs when a cancer is found that would not have gone on to cause symptoms or potentially may have resolved on its own (Smith et al., 2019). This is the major concern described earlier within the prostate cancer screening section of this module. Routine PSA screening has led to the overdiagnosis and in turn, overtreatment of many indolent prostate cancers. Overtreatment refers to treatments administered due to the identification of cancer that may not have ever been necessary. These can cause undesirable adverse effects, as well as add unnecessary healthcare costs (Kappen et al., 2019).

Barriers to Cancer Screening

There are numerous barriers to cancer screening, which are often multifactorial in etiology. The APRN serves a vital role in facilitating the screening process and ensuring patients receive proper education and timely cancer screening. Some of the most common barriers include the following:

- Socioeconomic status and demographics including income, age, and marital status;

- Accessibility to healthcare providers, healthcare services, and screening facilities;

- Insurance coverage and insurance type, including high out-of-pocket costs of care (deductibles, co-pays, coinsurance);

- Transportation and travel time;

- Psychosocial (anxiety and fear of the screening procedure, pain, and of the results);

- Forgetfulness;

- Lack of motivation;

- Lack of knowledge or understanding;

- Health behaviors: current smokers are less likely to undergo cancer screenings (Jang et al., 2019; Knight et al., 2015).

Risk Reduction among Cancer Survivors

Continued surveillance is essential for the early detection of new and recurrent cancers in cancer survivors. The American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) provides a blueprint of key recommendations for cancer survivors to follow for cancer prevention, which are summarized below.

- Consume a diet rich in whole grains, vegetables, fruits, and beans on a daily basis;

- Limit the consumption of 'fast foods' and other processed foods high in fat, starches, or sugars;

- Maintain a healthy weight range and avoid weight gain in adult life;

- Limit consumption of red and processed meat; eat no more than moderate amounts of red meat, such as beef, pork, and lamb, and eat little, if any, processed meat;

- Limit alcohol consumption (for cancer prevention, it is advisable to avoid alcohol);

- Maintain a physically active lifestyle as part of everyday life; walk more and sit less;

- Limit consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks; drink mostly water and unsweetened drinks;

- Do not use supplements for cancer prevention;

- Avoid tobacco use, make efforts to avoid second-hand tobacco exposure;

- Avoid excess sun exposure and practice sun safety when exposure is unavoidable;

- Mothers are advised to breastfeed their babies, which provides health benefits for both the mother and the baby (AICR, 2019).

Key Points

In summary, early detection offers the best chance of finding cancer early when it is most treatable. Prevention and early detection are the best and most effective treatments for cancer as they result in decreased morbidity and mortality. The development of risk profiles and the use of screening guidelines enhances screening efficacy and reduces healthcare costs and unnecessary spending (ACS, 2018b; Smith et al., 2019). Table 2 provides a summary of the key teaching points for cancer prevention and early detection.

Table 2

Key Teaching Points: Cancer Prevention and Early Detection

Smoking cessation counseling, including all forms of tobacco use, vaping, and any other illicit drug use. Cigarette smoking is the most preventable cause of cancer-related death in the U.S. |

Limit alcohol intake. |

Maintain a healthy weight through consumption of a healthy diet, rich in fiber, whole foods, fruits, and vegetables; limit sugar, salt, processed foods, and other high-fat, greasy foods. |

Adopt and maintain a physically active lifestyle. Adults should engage in 150 minutes of moderate intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity each week, preferably spread throughout the week. |

Avoid sun exposure, especially during the hours of 10 A.M. and 4 P.M., and cover exposed skin with sunscreen with a skin protection factor of 30 or higher. |

Avoid tanning beds, booths, and salons. There is no such thing as a ‘safe’ tanning bed. |

Identify and refer those at high risk for certain cancers to genetic counselors and for genetic testing. |

HPV causes most cervical, vulvar, vaginal, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers in women and most oropharyngeal, anal, and penile cancers in men. Routine HPV vaccination should be recommended for females and males starting at age 11 or 12 years but may begin as early as age 9. |

Females at average risk: o Screening for cervical cancer should begin at age 21 and continue in both vaccinated and unvaccinated women. o Women aged 40 and older should undergo annual mammogram. o Regular CRC screenings at age 45 – fecal occult blood test (FOBT); colonoscopy at age 50. |

Males at average risk o Aged 50 and older - annual PSA and DRE; o Regular CRC screenings at age 45 – fecal occult blood test (FOBT); colonoscopy at age 50. |

References

American Association of Nurse Practitioners. (2019). Scope of practice for nurse practitioners. https://storage.aanp.org/www/documents/advocacy/position-papers/ScopeOfPractice.pdf

American Cancer Society. (2017). ACS guidelines for nutrition and physical activity. http://www.cancer.org/healthy/eat-healthy-get-active/acs-guidelines-nutrition-physical-activity-cancer-prevention/guidelines.html

American Cancer Society. (2018a). Colorectal cancer: Early detection, diagnosis, and staging. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging.html

American Cancer Society. (2018b). American Cancer Society prevention and early detection guidelines. https://www.cancer.org/healthy/find-cancer-early/cancer-screening-guidelines/american-cancer-society-guidelines-for-the-early-detection-of-cancer.html

American Cancer Society. (2019a). Lung cancer screening guidelines. https://www.cancer.org/health-care-professionals/american-cancer-society-prevention-early-detection-guidelines/lung-cancer-screening-guidelines.html

American Cancer Society. (2019b). American Cancer Society recommendations for the early detections of breast cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/american-cancer-society-recommendations-for-the-early-detection-of-breast-cancer.html

American Cancer Society. (2019c). Cancer facts & figures 2019. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2019/cancer-facts-and-figures-2019.pdf

American Cancer Society. (2019d). Key statistics for lung cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

American Cancer Society. (2019e). American Cancer Society recommendation for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine use. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/infectious-agents/hpv/acs-recommendations-for-hpv-vaccine-use.html

American Institute for Cancer Research (2019). 10 cancer prevention recommendations. https://www.aicr.org/learn-more-about-cancer/infographics/10-recommendations-for-cancer-prevention.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). What is breast cancer screening? https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/basic_info/screening.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). HPV Cancers. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/cancer.html

Greene, H. (2016). Advanced oncology nursing certification review and resource manual (2nd ed.). (B. H. Gobel, S. Triest-Robertson, & W. H. Vogel). Oncology Nursing Society.

Howlader, N., Noone, A. M., Krapcho, M., Miller, D., Brest, A., Yu, M., Ruhl J, Tatalovich, Z., Mariotto, A., Lewis, D. R., Chen, H. S., Feuer, E. J., & Cronin, K. A. (2019). SEER cancer statistics review (CSR), 1975-2016. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016/sections.html

Itano, J. K. (2016). Core curriculum for oncology nursing (5th ed.). (J. Brant, F. Conde, & M. Saria, Eds.). Elsevier.

Jang, M. K., Hershberger, P. E., Kim, S., Collins, E. G., Quinn, L. T., Park, C. G., & Ferrans, C. E. (2019). Factors influencing surveillance mammography adherence among breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 46(6), 701-714. https://doi.org/10.1188/19.ONF.701-714.

Jenabi, E., & Poorolajal, J. (2015). The effect of body mass index on endometrial cancer: A meta-analysis. Public Health (Elsevier), 129(7), 872-880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.017

Kappen, S., Jurgens, V., Freitag, M. H., & Winter, A. (2019). Early detection of prostate cancer using prostate-specific antigen testing: An empirical evaluation among general practitioners and urologists. Cancer Management and Research, 11, 3079-3097. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S193325.

Knight, J. R., Kanotra, S., Siameh, S., Jones. J., Thompson, B., & Thomas-Cox, S. (2015). Understanding barriers to colorectal cancer screening in Kentucky. Preventing Chronic Disease, 12. https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2015/14_0586.htm

Loomans-Kropp, H. A., & Umar, A. (2019). Cancer prevention and screening: The next step in the era of precision medicine. Npj Precision Oncology, 3(3), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-018-0075-9.

Lubejko, B., & Wilson, B. (2019). Oncology nursing scope & standards of practice (1st ed.). Oncology Nursing Society.

McCance, K. L., & Heuther, S. E. (2014). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children (7th ed.). Mosby Elsevier

Moore, C., & Brewer, M. (2017). Endometrial cancer: Is this a new disease? American Society of Clinical Oncology Education Book, 37, 435-442. https://doi.org/10.14694/EDBK_175666

National Cancer Institute. (2017). Harms of cigarette smoking and health benefits of quitting. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/tobacco/cessation-fact-sheet#what-are-the-immediate-health-benefits-of-quitting-smoking

Nettina, S. M. (Ed.). (2019). Lippincott manual of nursing practice (11th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Papatla, K., Huang, M., & Slomovitz, B. (2016). The obese endometrial cancer patient: how do we effectively improve morbidity and mortality in this patient population? Annals of Oncology, 27(11), 1988-1994.

Polovich, M., Olsen, M., & LeFebvre, K. (2014). Chemotherapy and biotherapy guidelines and recommendations for practice (4th Ed.). Oncology Nursing Society.

Smith, R. A., Andrews, K. S., Brooks, D., Fedewa, S. A., Manassaram-Baptiste, D., Saslow, D., & Wender, R. C. (2019). Cancer screening in the United States, 2019: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69(3), 184-210. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21557

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program. (2018). SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2014. National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/.

Wolf, A., Fontham, E., Church, T., Flowers, C., Guerra, C., LaMonte, S., Etzioni, R., McKenna, M. T., Oeffinger, K. C., Shih, Y. T., Walter, L. C., Andrews, K. S., Brawley, O. W., Brooks, D., Fedewa, S. A., Manassaram-Baptiste, D., Siegel, R. L., Wender, R. C., & Smith, R. (2018). Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68(4), 250-281. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21457

World Health Organization. (2019a). Cancer prevention. https://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/en/

World Health Organization. (2019b). Early detection of cancer. https://www.who.int/cancer/detection/en/

Yarbro, C. H., Wujcik, D., & Gobel, B. H. (Eds.). (2018). Cancer nursing: Principles and practice (8th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.