The purpose of this course is designed for nurses to understand the pathophysiology, risk and protective factors, signs and symptoms, diagnosis, treatment/management (both dietary changes and pharmacology), nursing care/implications, and future research/trends in Cholesterol Management, Coaching, and Patient Education.

...purchase below to continue the course

ften already show the first stages of atherosclerosis. Because of a lack of long-term research for this younger age group, statin recommendations are reserved only for those with the highest risk (AHA News, 2018). After age 40, the health care provider will want to use an equation to calculate the 10-year risk of experiencing cardiovascular disease or stroke (AHA, 2019). For people 40 to 75-years-old without evidence of heart disease, the guidelines use the calculation to place each patient into four classifications of risk: low, borderline, intermediate and high (AHA News, 2018).

Cholesterol testing is done by monitoring the serum cholesterol, therefore, requiring a simple blood sample. Ideally, the patient should be fasting for 9 to12 hours before the test. A blood test called a lipoprotein panel can measure the cholesterol levels. Before the test, the patient needs to fast (not eat or drink anything but water) for 8 to 12 hours (AHA, 2019). The lipoprotein panel offers information related to:

- Total cholesterol - a measure of the total amount of cholesterol in the blood. It includes both LDL cholesterol and HDL cholesterol

- LDL (bad) cholesterol - the main source of cholesterol buildup and blockage in the arteries.

- HDL (good) cholesterol - HDL helps remove cholesterol from the arteries.

- Non-HDL - this number is the total cholesterol minus the HDL. The non-HDL includes LDL and other types of cholesterol such as VLDL (very-low-density lipoprotein)

- Triglycerides - another form of fat in the blood that can raise the risk of heart disease, especially in women (Medline Plus, 2019b).

Table 1 (below) gives the target ranges for all of the above components, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH, 2019a).

Table 1: Cholesterol Targets by Age

(National Institutes of Health, 2019a)

Rather than providing target cholesterol values, the AHA/ACC recommends that the focus of care for patients with unhealthy cholesterol levels be on reducing the total LDL cholesterol from baseline (Shub & Oji, 2018). Table 2 (below) indicates some general risk categories based on lab test results for a standard lipid panel in adults over the age of 18 according to the NIH.

Table 2: Risk Stratification Table Based on Lipid Panel Results

Total Cholesterol Results | Total Cholesterol Category |

Less than 200mg/dL | Desirable |

200-239 mg/dL | Borderline high |

240mg/dL and above | High

|

LDL Cholesterol Results | LDL Cholesterol Category |

Less than 100mg/dL | Optimal |

100-129mg/dL | Near-optimal/above optimal |

130-159 mg/dL | Borderline high |

160-189 mg/dL | High |

190 mg/dL and above | Very High |

HDL Cholesterol Results | HDL Cholesterol Category |

60 mg/dL and higher | Considered protective against heart disease |

40-59 mg/dL | The higher, the better |

Less than 40 mg/dL | A major risk factor for heart disease |

(Medline, 2019a)

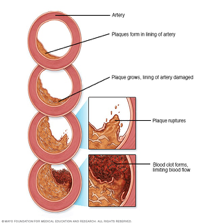

The healthcare practitioner may order a heart scan to get a better understanding of the risk of heart disease if the treatment plan is uncertain. A heart scan uses a specialized X-ray technology called multidetector-row or multi-slice computerized tomography (CT), which creates multiple images of plaque deposits in the blood vessels. The imaging test provides an early look at levels of plaque and is communicated via the coronary artery calcification (CAC) score (Mayo Clinic, 2019b).

Risk Factors

In addition to the hallmark risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as hypertension, hyperglycemia, smoking, and obesity, additional factors that should be screened for by the nurse during the history portion of any primary care or health-maintenance visit include family history, age/gender, physical activity habits, dietary habits, stress, and sleep habits. This allows the healthcare a broader picture of a person's cardiovascular risk over the next 10 years, as each own can impact cholesterol numbers. Hypertension and hyperglycemia recommendations are complex, varied, and outside of the scope of this particular module, other than to note that these chronic conditions drastically increase an individual’s risk for hypercholesterolemia and should be managed appropriately based on their own evidence-based guidelines (AHA News, 2018; Nursing in Practice, 2016).

Smoking

Smoking damages the blood vessels and increases the risk of plaque buildup. It also reduces the amount of HDL in the blood. This is a problem because HDLs absorb cholesterol and carry it back to the liver, where it is flushed from the body. High levels of HDLs in the blood protect against heart disease. Experts estimate that a smoker is two to four times more likely to develop heart disease than a person who doesn’t smoke. The risk is even greater if the smoker struggles with high cholesterol (Nursing in Practice, 2016).

When patients quit smoking, research suggests a rapid increase in HDL concentrations - in less than three weeks. This emphasizes that some, at least, of the adverse effects of smoking appear to be rapidly reversible on quitting, strengthening the argument for encouraging smokers to quit (Nursing in Practice, 2016).

Smoking cessation improves the HDL cholesterol level. The benefits occur quickly:

- Within 20 minutes of quitting, the blood pressure and heart rate recover from the cigarette-induced spike.

- Within three months of quitting, the blood circulation and lung function begin to improve.

- Within a year of quitting, the risk of heart disease is half that of a smoker (Mayo Clinic, 2019c).

Obesity

The pathophysiology of typical dyslipidemia observed in obesity is multifactorial and includes hepatic overproduction of VLDL, decreased circulating TG lipolysis, impaired peripheral FFA (free fatty acids) trapping, increased FFA fluxes from adipocytes to the liver and other tissues and the formation of small dense LDL. Treatment of the hypercholesterolemia is paramount to treating a symptom and yet ignoring the disease. Treatment should instead be aimed at weight loss by increased exercise and a healthy, well-balanced diet with a reduction in total calorie intake, saturated fats, and sodium. Lipid-lowering medications should then be discussed if lifestyle changes are insufficient (NIH, 2019a).

Family History

Patients may inherit a family history of high cholesterol. Familial hypercholesterolemia is a genetic disorder, caused by a defect on chromosome 19. The defect makes the body unable to remove LDL or ‘bad’ cholesterol. This results in a high level of LDL in the blood. In addition, they are at risk for hypertriglyceridemia (high blood triglyceride levels) (Nursing in Practice, 2016).

Ethnicity and gender also affect a patient’s chances of inheriting a greater risk of developing high levels of cholesterol. People of South Asian origin tend to have more harmful types of LDL cholesterol and less helpful types of HDL cholesterol, compared to people with European ancestry. South Asian people may also have worse ratios of LDL to HDL cholesterol, which aren’t explained by differences in diet. Additionally, they are more likely to have higher triglyceride levels (Nursing in Practice, 2016).

Of course, it is difficult to remove the factors of nature, nurture and lifestyle across ethnic groups, but ethnicity and cultural practices should be considered when supporting people in primary care (Nursing in Practice, 2016).

Age and Gender

Everyone’s risk for high cholesterol goes up with age. This is because as we age, our bodies can’t clear cholesterol from the blood as well as they could when we were younger. This leads to higher cholesterol levels, which raise the risk of heart disease and stroke. Until around age 55 (or until menopause), women tend to have lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL, or “bad”) levels than men do. At any age, men tend to have lower high-density lipoprotein (HDL, or “good”) cholesterol than women do (Mayo Clinic, 2019c).

Physical Activity

Exercise and physical activity are great ways to feel better, boost health and have fun. For most healthy adults, the Department of Health and Human Services recommends:

- At least 150 minutes a week of moderate aerobic activity or 75 minutes a week of vigorous aerobic activity, or a combination of moderate and vigorous activity. The AHA guidelines suggest that you spread this exercise throughout the week. Examples include running, walking or swimming. Even small amounts of physical activity are helpful, and accumulated activity throughout the day adds up to provide health benefits.

- Strength training exercises for all major muscle groups at least two times a week. Examples include lifting free weights, using weight machines or doing body-weight training (Mayo Clinic, 2019a).

Activities should be spread throughout the week. If the goal is to lose weight, meet specific fitness goals or get even more benefits, the patient may need to ramp up the moderate aerobic activity to 300 minutes or more a week. Any patient should check with their primary healthcare provider before starting a new exercise program, especially if there are any concerns about the level of fitness, haven't exercised for a long time, have chronic health problems, such as heart disease, diabetes or arthritis (Mayo Clinic, 2019a).

Diet

Heart-healthy lifestyle changes include a diet to lower cholesterol. The DASH eating plan is one example. Another is the Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes (TLC) diet, which recommends choosing healthier fats, limiting foods with cholesterol, increasing fiber intake, eat lots of fruits, vegetables and fish high in omega3 fatty acids, limiting salt and alcohol (Medline, 2019c). Next is a closer look at each of these.

Choose healthier fats. One should limit both total fat and saturated fat. Depending upon how many calories eaten per day, here are the maximum amounts of fats permitted:

- No more than 25 to 35% of the daily calories should come from dietary fats.

- Less than 7% of daily calories should come from saturated fat.

(Medline, 2019c)

Saturated fat is a bad fat because it raises the LDL (bad cholesterol) level more than anything else in the diet. It is found in some meat, dairy products, chocolate, baked goods, and deep-fried and processed foods (Medline, 2019c).

Trans fat is another bad fat; it can raise LDL and lower HDL (good cholesterol). Trans fat is mostly in foods made with hydrogenated oils and fats, such as stick margarine, crackers, and french-fries (Medline, 2019c). Instead of these bad fats, encourage healthier fats, such as lean meat, nuts, and unsaturated oils like canola, olive, and safflower oils (Medline, 2019c).

Limit foods with cholesterol. When trying to lower cholesterol, the patient should have less than 200 mg a day of cholesterol. Cholesterol is in foods of animal origin, such as liver and other organ meats, egg yolks, shrimp, and whole milk dairy products (Medline, 2019c).

Eat plenty of soluble fiber. Foods high in soluble fiber help prevent the digestive tract from absorbing cholesterol. These foods include:

- Whole-grain cereals such as oatmeal and oat bran

- Fruits such as apples, bananas, oranges, pears, and prunes

- Legumes such as kidney beans, lentils, chickpeas, black-eyed peas, and lima beans (Medline, 2019d)

Eat lots of fruits and vegetables. A diet rich in fruits and vegetables can increase important cholesterol-lowering compounds in the diet. These compounds, called plant stanols or sterols, work like soluble fiber (Medline, 2019c).

Eat fish that are high in omega-3 fatty acids. These acids won't lower the LDL level, but they may help raise the HDL level. They may also protect the heart from blood clots and inflammation and reduce the risk of a heart attack. Fish that are a good source of omega-3 fatty acids include salmon, tuna (canned or fresh), and mackerel. Try to eat these fish two times a week (Medline, 2019c).

Limit salt. The amount of sodium (salt) should be no more than 2,300 milligrams (about 1 teaspoon of salt) a day. That includes all sodium, whether it was added in cooking or at the table, or already present in food products. Limiting salt won't lower the cholesterol, but it can lower the risk of heart diseases by helping to lower the blood pressure. Sodium can be reduced by choosing low-salt and "no added salt" foods and seasonings at the table or while cooking (Medline, 2019c).

Limit alcohol. Alcohol adds extra calories, which can lead to weight gain. Being overweight can raise the LDL level and lower the HDL level. Too much alcohol can also increase the risk of heart diseases because it can raise blood pressure and triglyceride level. One drink is a glass of wine, beer, or a small amount of hard liquor, and the recommendation is that:

- Men should have no more than two drinks containing alcohol a day

- Women should have no more than one drink containing alcohol a day (Medline, 2019c).

Nutrition labels can be helpful to figure out how much fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, fiber, and sodium is in foods (Medline, 2019c).

Stress

Stress has physiological effects; it causes veins to rupture and serum cholesterol levels to rise. Stress is related to the production of higher levels of LDL, but research is difficult to conduct because of the variety of confounders. A Scandinavian study enrolled more than 40,000 workers in a study of workplace stress and cholesterol and found a direct link with persistently high levels of stress and greater production of LDL. However, the diet was not assessed and only one marker was used for measuring stress levels. Other evidence points to the effects of chronic stress on cholesterol levels. Animals such as zebras have episodic periods of stress, which their systems can deal with, whereas humans are more likely to suffer prolonged chronic periods of anxiety and stress, which leads to cell damage and cholesterol production. If there are three risk factors —smoking, high blood cholesterol and a family history of heart disease — the risk for heart disease increases tenfold (Nursing in Practice, 2016).

Sleep

Researchers have discovered that both too much and too little sleep have a negative impact on cholesterol levels. Sleep duration for both males and females are closely associated with serum lipid and lipoprotein levels. Other research studies confirm this but also have found that snoring leads to the lowering of the good HDL cholesterol. This could be due to other factors like obesity and stress, as it is difficult to separate all possible confounders. Another study suggests that shortened sleep makes people want a more saturated diet and to have less inclination to exercise. Lack of sleep also heightens stress and general anxiety levels, which again links to increased levels of LDL (Nursing in Practice, 2016).

Management

Importantly, the management of cholesterol is viewed as a shared endeavor between the patient and healthcare practitioner. The healthcare practitioner should validate that patients understand the implications of hypercholesterolemia and the healthcare plan specific to them (Nursing in Practice, 2016). The main goal of cholesterol-lowering treatment is to lower the LDL level enough to reduce the risk of developing heart disease or having a heart attack. The American College of Cardiology offers a calculator tool on their website which allows nurses and other healthcare providers a quick and easy way to calculate a patient’s 10-year risk, using their age, gender, race, current blood pressure reading, current lipid panel results (total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL), as well as some history items such as smoking habits, history of diabetes, and medication history (ACC, n.d.). See Figure 2 below for the schematic of how to then utilize that classified risk from the AHA guidelines (Grundy et al., 2018).

Figure 2: AHA Primary Prevention Risk Schematic

(Grundy et al., 2018)

Pharmacology

The present guidelines continue to emphasize the importance of a clinician-patient risk discussion. In those with a 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥7.5%, it is recommended that the discussion occur before a statin prescription is written. This frank discussion, as recommended in the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines, should consider whether ASCVD risk factors have been addressed, evaluate whether an optimal lifestyle has been implemented, and review the potential for statin benefit versus the potential for adverse effects and drug-drug interactions. Then, based on individual characteristics and including an informed patient preference in shared decision-making, a risk decision about statin therapy can be made (Grundy et al., 2019).

Statins inhibit cholesterol synthesis in the liver by blocking the protein HMG-CoA reductase from making cholesterol. Liver cells try to compensate for the low cholesterol by synthesizing more LDL receptors on the cell surface to increase LDL uptake from the blood. Statins are the most common medicine used to treat high blood cholesterol in people who are 10 years old or older. In certain cases, doctors may prescribe statins in people younger than 10 years old (NIHLB, 2019).

Examples: Atorvastatin (Lipitor), Fluvastatin (Lescol, Lescol XL), Lovastatin (Altoprev, Mevacor), Pitavastatin (Livalo), Pravastatin (Pravacol), Rosuavastatin (Crestor), and Simvastatin (Zocor) (Burchum & Rosenthal, 2016).

Common or serious adverse reactions: Myopathy, hepatotoxicity. Contraindications active or chronic liver disease and pregnancy (Burchum & Rosenthal, 2016).

In a meta-analysis of 5 random controlled trials (RCTs), high-intensity statins compared with moderate-intensity statin therapy, significantly reduced major vascular events by 15% with no significant reduction in coronary deaths. Large absolute LDL-C reduction was associated with a larger proportional reduction in major vascular events (Grundy et al., 2019).

PCSK9 inhibitors lower LDL cholesterol by decreasing the destruction of LDL receptors in the liver, which helps remove and clear LDL cholesterol from the blood (NIHLB, 2019).

Examples: Evolocumab (Repatha), Alirocumab (Praluent) given subcutaneous or intravenous infusion (Chaudhary, Garg, Shah, & Sumner, 2017).

Adverse effects: Nasopharyngitis, erythema, swelling, pain, and tenderness at the injection site. Back pain and nausea with Evolocamab (Chaudhary et al., 2017).

Bile acid sequestrants block the reabsorption of bile acids and increase conversion of cholesterol to bile acids. This has the effect of lowering plasma cholesterol levels (NIHLB, 2019).

Examples: Colesevelam (Welchol), cholestyramine (Questran, Prevalite), colestipol (Cholstid) (Burchum & Rosenthal, 2016).

Adverse effects: Limited to the GI tract. Constipation is the main complaint but some patients complain of bloating, indigestion, and nausea (Burchum & Rosenthal, 2016).

Ezetimibe blocks dietary cholesterol from being absorbed in the intestine (NIHLB, 2019).

Examples: Zetia, Ezetrol (Burcham & Rosenthal, 2016).

Adverse effects: Myopathy, rhabdomyolysis, hepatitis, pancreatitis, and thrombocytopenia (Burcham & Rosenthal, 2016).

Fibrates promote the removal of VLDL cholesterol, part of non-HDL (NIHLB, 2019).

Examples: Gemfrifrozil (Lopid), fenofibrate (Tricor, Antara, Lofibra, Triglide, Lipofen, Lipidil), fenofibric acid (TriLipix, Fibricor) (Burcham & Rosenthal, 2016).

Adverse effects and drug interactions: GI disturbances such as nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Gallstones, myopathy, and liver injury have been reported. Gemfibrozil displaces warfarin from plasma albumin thereby increasing anticoagulant effects. (Burcham & Rosenthal, 2016).

Ezetimibe is the most commonly used non-statin agent. It lowers LDL-C levels by 13% to 20% and has a low incidence of side effects. Bile acid sequestrants reduce LDL-C levels by 15% to 30% depending on the dose. Bile acid sequestrants are not absorbed and do not cause systemic side effects, but they are associated with gastrointestinal complaints (e.g., constipation) and can cause severe hypertriglyceridemia when fasting triglycerides are ≥300 mg/dL (≥3.4 mmol/L). PCSK9 inhibitors are powerful LDL-lowering drugs. They generally are well-tolerated, but long-term safety remains to be proven. Two categories of triglyceride-lowering drugs, niacin, and fibrates, may also mildly lower LDL-C levels in patients with normal triglycerides. They may be useful in some patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia, but in the present document, they are not listed as LDL-lowering drugs (Grundy et al., 2019).

Under certain circumstances, non-statin medications (ezetimibe, bile acid sequestrants, and PCSK9 inhibitors) may be useful in combination with statin therapy. The addition of a bile acid sequestrant or ezetimibe to a statin regimen increases the magnitude of LDL-C lowering by approximately 15% to 30% and 13% to 20%, respectively. The addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor to a statin regimen has been shown to further reduce LDL-C levels by 43% to 64% (Grundy et al., 2019).

Lomitapide blocks the liver from releasing VLDL cholesterol into the blood. It is used only in patients who have familial hypercholesterolemia.

Example: Juxtapid (NIH, 2019b).

Adverse effect: hepatoxicity (NIH, 2019b).

Mipomersen decreases levels of non-HDL cholesterol in the blood. It is used only in patients who have familial hypercholesterolemia. It is approved by the FDA only as an orphan drug for use in HoFH, a relatively rare genetic condition. Ongoing clinical trials are being conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of mipomersen in varying populations. It is given only by subcutaneous injection (Wong & Goldberg, 2014).

Example: Kynamro

Adverse effects: hepatoxicity, injection-site reactions such as erythema, pruritus, and pain. There were also reports of influenza-like symptoms such as fatigue, pyrexia, chills, malaise, myalgia, and arthralgia (Wong & Goldberg, 2014).

Niacin (nicotinic acid) decreases bad LDL cholesterol and triglycerides and raises HDL cholesterol. However, despite favorable effects on lipid levels, niacin does little to improve outcomes, as shown by the AIM-HIGH trial in 2011. The trial, sponsored by the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, was designed to answer an important question: Does raising HDL cholesterol with Niacin reduce the risk of CV events? (Burcham & Rosenthal, 2016).

Examples: Niacor, Niaspan (Burcham & Rosenthal, 2016).

Adverse effects: intense flushing, GI upset, and liver injury (Burcham & Rosenthal, 2016).

Lipoprotein apheresis- Some patients with familial hypercholesterolemia may benefit from lipoprotein apheresis to lower their blood cholesterol levels. Lipoprotein apheresis is a dialysis-like process in which LDL cholesterol is removed from the blood by a filtering machine, with the remainder of the blood being returned to the patient (NIHLB, 2019).

Natural Products

Stanols and Sterols

The use of foods containing added plant stanols or sterols is an option in conventional treatment for high cholesterol levels. Stanols and sterols are also available in dietary supplements. The evidence for the effectiveness of the supplements is less extensive than the evidence for foods containing stanols or sterols, but in general, studies show that stanol or sterol supplements, taken with meals, can reduce cholesterol levels. Some foods and dietary supplements that contain stanols or sterols are permitted to carry a health claim, approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), saying that they may reduce the risk of heart disease when consumed in appropriate amounts (NIH, 2019a).

Plant stanols and sterols consist of the following: certain vegetable oils (eg, canola), nuts (walnuts are a good source), certain fruits, most beans, and other vegetables. They are also found in some cholesterol-lowering margarine, commonly advertised as "buttery spreads" (Burchum & Rosenthal, 2016).

Flaxseed

Studies of flaxseed preparations to lower cholesterol levels suggest possible beneficial effects for some types of flaxseed supplements, including whole flaxseed and flaxseed lignans but not flaxseed oil. The effects were stronger for women (especially postmenopausal women) than men and people with higher initial cholesterol levels (NIH, 2019a).

Green Tea

There is some limited evidence that suggests green tea may have a modest cholesterol-lowering effect (NIH, 2019a).

Garlic

A recent review of the research on garlic supplements concluded that they can lower cholesterol if taken for more than 2 months, but their effect is modest in comparison with the effects of cholesterol-lowering drugs (NIH, 2019a).

Oats and Oat Bran

Long-term dietary intake of oats or oat bran can have a beneficial effect on blood cholesterol. Studies suggest that there is a beneficial effect of oat consumption on reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) by lowering total and LDL-cholesterol (NIH, 2019a).

Red Yeast Rice

The FDA has determined that red yeast rice that contains more than trace amounts of a substance called monacolin K is an unapproved new drug and cannot be sold legally as a dietary supplement. Monacolin K is chemically identical to the cholesterol-lowering drug lovastatin, and some red yeast rice contains substantial amounts of this substance. Red yeast rice that contains monacolin K may lower blood cholesterol levels, but it can also cause the same types of side effects and drug interactions as lovastatin (NIH, 2019a).

Researchers have not reported results of many studies of red yeast rice products that contain little or no monacolin K, so whether these products have any effect on blood cholesterol is unknown (NIH, 2019a).

Research

Learn about the following ways in which the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) continues to translate current research and science into improved health for people with high blood cholesterol:

- NHLBI Systematic Evidence Reviews Support Development of Guidelines for Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Continue to perform systematic reviews of the latest science. These reviews help partner organizations update their clinical guidelines, which health professionals use to treat adults who have high blood cholesterol. Visit Managing Blood Cholesterol in Adults Systematic Evidence Review From the Cholesterol Expert Panel, 2013 for more information (NHLBI, 2019).

- NIH Task Force to Develop First Nutrition Strategic Plan. Collaborate with other institutes to develop a 10-year plan to increase research in nutrition, including experimental design and training. Visit NIH task force formed to develop the first nutrition strategic plan for more information (NHLBI, 2019).

- Federal Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Continue to provide medical, nutritional, and other scientific expertise to the United States Department of Agriculture and HHS that publish the 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans external link with information about the latest science-based nutritional recommendations (NHLBI, 2019).

- Global Leadership in Cardiovascular Health. Serve as a global leader and respond to legislative calls to increase U.S. global health efforts. The Health Inequities and Global Health Branch seek to stimulate global health research, education, and training for many conditions, including high blood cholesterol (NHLBI, 2019).

Conclusion

The following are the 10 Take-Home Messages to Reduce Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Through Cholesterol Management, as quoted from the 2018 AHA guidelines:

- In all individuals, emphasize a heart-healthy lifestyle across the life course. A healthy lifestyle reduces atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk at all ages. In younger individuals, a healthy lifestyle can reduce the development of risk factors and is the foundation of ASCVD risk reduction. In young adults, 20 to 39 years of age, an assessment of lifetime risk facilitates the clinician-patient risk discussion (see No. 6) and emphasizes intensive lifestyle efforts. In all age groups, lifestyle therapy is the primary intervention for metabolic syndrome (Grundy et al., 2019).

- In patients with clinical ASCVD, reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) with high-intensity statin therapy or maximally tolerated statin therapy. The more LDL-C is reduced on statin therapy, the greater will be subsequent risk reduction. Use a maximally tolerated statin to lower LDL-C levels by ≥50% (Grundy et al., 2019).

- In very high-risk ASCVD, use an LDL-C threshold of 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) to consider the addition of non-statins to statin therapy. Very high-risk includes a history of multiple major ASCVD events or 1 major ASCVD event and multiple high-risk conditions. In very high-risk ASCVD patients, it is reasonable to add ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin therapy when the LDL-C level remains ≥70 mg/dL (≥1.8 mmol/L). In patients at very high risk whose LDL-C level remains ≥70 mg/dL (≥1.8 mmol/L) on maximally tolerated statin and ezetimibe therapy, adding a PCSK9 inhibitor is reasonable, although the long-term safety (>3 years) is uncertain and cost-effectiveness is low at mid-2018 list prices (Grundy et al., 2019).

- In patients with severe primary hypercholesterolemia (LDL-C level ≥190 mg/dL [≥4.9 mmol/L]), without calculating 10-year ASCVD risk, begin high-intensity statin therapy. If the LDL-C level remains ≥100 mg/dL (≥2.6 mmol/L), adding ezetimibe is reasonable. If the LDL-C level on statin plus ezetimibe remains ≥100 mg/dL (≥2.6 mmol/L) and the patient has multiple factors that increase subsequent risk of ASCVD events, a PCSK9 inhibitor may be considered, although the long-term safety (>3 years) is uncertain and economic value is uncertain at mid-2018 list prices(Grundy et al., 2019).

- In patients 40 to 75 years of age with diabetes mellitus and LDL-C ≥70 mg/dL (≥1.8 mmol/L), start moderate-intensity statin therapy without calculating 10-year ASCVD risk. In patients with diabetes mellitus at higher risk, especially those with multiple risk factors or those 50 to 75 years of age, it is reasonable to use a high-intensity statin to reduce the LDL-C level by ≥50% (Grundy et al., 2019).

- In adults, 40 to 75 years of age evaluated for primary ASCVD prevention, have a clinician-patient risk discussion before starting statin therapy. Risk discussion should include a review of major risk factors (e.g., cigarette smoking, elevated blood pressure, LDL-C, hemoglobin A1C [if indicated], and calculated 10-year risk of ASCVD); the presence of risk-enhancing factors (see No. 8); the potential benefits of lifestyle and statin therapies; the potential for adverse effects and drug-drug interactions; consideration of costs of statin therapy; and patient preferences and values in shared decision-making (Grundy et al., 2019).

- In adults 40 to 75 years of age without diabetes mellitus and with LDL-C levels ≥70 mg/dL (≥1.8 mmol/L), at a 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥7.5%, start a moderate-intensity statin if a discussion of treatment options favors statin therapy. Risk-enhancing factors favor statin therapy (see No. 8). If risk status is uncertain, consider using coronary artery calcium (CAC) to improve specificity (see No. 9). If statins are indicated, reduce LDL-C levels by ≥30%, and if the 10-year risk is ≥20%, reduce LDL-C levels by ≥50% (Grundy et al., 2019).

- In adults 40 to 75 years of age without diabetes mellitus and 10-year risk of 7.5% to 19.9% (intermediate risk), risk-enhancing factors favor the initiation of statin therapy (see No. 7). Risk-enhancing factors include family history of premature ASCVD; persistently elevated LDL-C levels ≥160 mg/dL (≥4.1 mmol/L); metabolic syndrome; chronic kidney disease; history of preeclampsia or premature menopause (age <40 years); chronic inflammatory disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or chronic HIV); high-risk ethnic groups (e.g., South Asian); persistent elevations of triglycerides ≥175 mg/dL (≥1.97 mmol/L); and, if measured in selected individuals, apolipoprotein B ≥130 mg/dL, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein ≥2.0 mg/L, ankle-brachial index <0.9 and lipoprotein (a) ≥50 mg/dL or 125 nmol/L, especially at higher values of lipoprotein (a). Risk-enhancing factors may favor statin therapy in patients at a 10-year risk of 5-7.5% (borderline risk) (Grundy et al., 2019).

- In adults 40 to 75 years of age without diabetes mellitus and with LDL-C levels ≥70 mg/dL to 189 mg/dL (≥1.8-4.9 mmol/L), at a 10-year ASCVD risk of ≥7.5% to 19.9%, if a decision about statin therapy is uncertain, consider measuring CAC. If CAC is zero, treatment with statin therapy may be withheld or delayed, except in cigarette smokers, those with diabetes mellitus, and those with a strong family history of premature ASCVD. A CAC score of 1 to 99 favors statin therapy, especially in those ≥55 years of age. For any patient, if the CAC score is ≥100 Agatston units or ≥75th percentile, statin therapy is indicated unless otherwise deferred by the outcome of clinician-patient risk discussion (Grundy et al., 2019).

- Assess adherence and percentage response to LDL-C–lowering medications and lifestyle changes with repeat lipid measurement 4 to 12 weeks after statin initiation or dose adjustment, repeated every 3 to 12 months as needed. Define responses to lifestyle and statin therapy by percentage reductions in LDL-C levels compared with baseline. In ASCVD patients at very high-risk, triggers for adding nonstatin drug therapy are defined by threshold LDL-C levels ≥70 mg/dL (≥1.8 mmol/L) on maximal statin therapy (see No. 3) (Grundy et al., 2019).

Screening and managing cholesterol levels is a public health priority considering the prevalence of high cholesterol. Nurses play a critical role in the education of patients. Patient and family education should exist throughout the continuum of care. A team of healthcare providers should teach the patient and loved ones about disease management, medications, post-discharge management, and advice on when and how to seek medical attention (Marcus, 2014).

Many other providers and practitioners play a crucial part in patient education and counseling, including dieticians for healthy diets, counselors for smoking cessation and stress reduction, physician and primary care providers for medication regulation, exercise prescriptions, and oversight of compliance. Each provider should work individually and collaboratively. Case managers can become facilitators for recognizing gaps in patient education and putting an appropriate plan in place given the patient's needs (Marcus, 2014).

“Tools discussed should be highlighted at screening checks so that patients can track their own health and wellbeing. Although successful treatments are available, prevention is always the most cost-effective solution to health problems” (Halloran, 2014).

References

American College of Cardiology (n.d.) ACSVD 10-year Risk Estimator Plus. Retrieved on August 2, 2019 from http://tools.acc.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator-Plus/#!/calculate/estimate/

American Heart Association News (2018). Cholesterol should be on everyone’s radar, beginning early in life. Retrieved from https://www.heart.org/en/news/2018/11/10/new-guidelines-cholesterol-should-be-on-everyones-radar-beginning-early-in-life

American Heart Association (2018). Life’s Simple 7 for kids. Retrieved from

http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Educator/FortheGym2/BasketballSkills/-/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/HealthyKids/LifesSimple7forKids/Lifes-Simple-7-for-Kids_UCM_466610_SubHomePage.jsp?appName=MobileApp

Burchum, J. & Rosenthal, L. (2016). Lehne’s pharmacology for nursing care. (9th ed.).

St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Knowing the risk for high cholesterol. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/cholesterol/risk_factors.htm

Chaudhary, R., Garg, J., Shah, N., & Sumner A. (2017). PC5K9 inhibitors: A new era of lipid

lowering therapy. World Journal of Cardiology, 9(2),76-91.

Grundy, S., Stone, N., Bailey, A., Beam, C., Birtcher, K., Blumenthal, R…Yeboak, J. (2018).

AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation, 139(25), 1082-1143.

Halloran, L, (2014). Clinical implications of new cholesterol guidelines. The Journal for Nurse

Practitioners 10 (10) November/December.

Marcus, C. (2014). Strategies for improving quality of verbal patient and family education: A

review of the literature and creation of the EDUCATE model. Health Psychology

Behavioral Medicine, 2(1), 482-495. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2014.900450

Marcel, C., & Engelke, Z. (2018a). Dietary saturated fat and cholesterol: Risk for coronary artery disease. CINAHL Nursing Guide.

Marcel, C., & Engelke, Z. (2018b). Evidenced based care sheet- Cholesterol. CINAHL Nursing Guide.

Mayo Clinic (2019a). Exercise: 7 benefits of regular physical activity. Retrieved from

https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/fitness/in-depth/exercise/art-20048389

Mayo Clinic (2019b). Heart scan (coronary calcium scan). Retrieved from

https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/heart-scan/about/pac-20384686

Mayo Clinic (2019c). High cholesterol. Retrieved from https://www.drugs.com/mcd/high- cholesterol#

Medline Plus, (2019a). Cholesterol levels. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/cholesterol-levels/

Medline plus (2019b). Cholesterol levels: what you need to know. Retrieved from

https://medlineplus.gov/cholesterollevelswhatyouneedtoknow.html

Medline Plus (2019c). How to lower cholesterol with diet. Retrieved from

https://medlineplus.gov/howtolowercholesterolwithdiet.html

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (2019) High blood cholesterol. Retrieved from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/high-blood-cholesterol

National Institutes of Health (2019a). High cholesterol and natural products: What the science says. Retrieved from https://nccih.(NIH, 2019, .gov/health/providers/digest/cholesterol-science

National Institutes of Health (2019b). LiverTox: Clinical and research information on liver injury. Retrieved from https://livertox.nih.gov/Lomitapide.htm

Nursing in Practice (2016). Cholesterol-lowering. Retrieved from

https://www.nursinginpractice.com/article/cholesterol-lowering

Schub, E., & Oji, O. (2018). Stroke and cholesterol. CINAHL Evidenced-based care sheet. CINAHL Nursing Guide.

WebMD (2019). Heart disease and lowering cholesterol. Retrieved from

https://www.webmd.com/heart-disease/guide/heart-disease-lower-cholesterol-risk#1

Wong, E., & Goldberg, T. (2014). A novel antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor to the management of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 39(2), 19-122.