About this course:

The purpose of this activity is to educate the learner regarding domestic violence and sexual violence statistics, risk factors, prevention, and the most up-to-date best practices for the evidenced-based care of survivors.

Course preview

Please note: This course is not yet approved for providing the newly required Domestic and Sexual Violence training in Massachusetts. If you would like notification for when this approval is issued please contact support@nursingce.com

If you are not licensed in Massachusetts, this course is still ANCC accredited to provide 3 contact hours of CE.

The purpose of this activity is to educate the learner regarding domestic violence and sexual violence statistics, risk factors, prevention, and the most up-to-date best practices for the evidenced-based care of survivors.

At the completion of this activity, the participant should be able to:

- explore the incidence and prevalence of domestic violence (DV) and sexual violence (SV);

- discuss the characteristics of perpetrators of DV and SV and outline the patterns of control utilized most commonly;

- summarize the impacts of DV and SV on various vulnerable populations, including health impacts, emotional impacts, short-term and long-term effects, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD);

- contrast risk factors, protective factors, and methods to prevent DV and SV;

- recognize common indicators of abuse that healthcare providers should be watchful for;

- explore screening tools for DV and SV to help healthcare providers identify DV and SV early for immediate intervention;

- consider the individual needs of each survivor of DV and SV and the importance of delivering appropriate information, validation, and support;

- develop an understanding of available community resources for survivors including, but not limited to hotlines, shelters, support groups, advocacy groups, and legal aid;

- interpret DV and SV laws related to mandatory reporting within the United States;

Domestic violence (DV) and sexual violence (SV) are national healthcare issues, and all healthcare providers should be fully prepared to skillfully care for those impacted whenever necessary. The nurse or healthcare provider should have specific knowledge of DV and SV indicators, risk factors, assessment techniques, and management skills to provide prompt intervention. Survivors of DV and SV should be partnered with local resources to support their immediate and ongoing needs. Further, the healthcare provider should be aware of local and state laws that govern their practice upon the recognition of survivors of DV and SV.

Defining the Terms

As defined by the U.S. Department of Justice (2018), DV is "any felony or misdemeanor crime of violence committed by a current or former spouse or intimate partner of the [survivor], by a person with whom the [survivor] shares a child in common, by a person who is cohabitating with or has cohabitated with the [survivor] as a spouse or intimate partner, by a person similarly situated to a spouse of the [survivor] under the domestic or family violence laws of the jurisdiction receiving grant monies, or by any other person against an adult or youth [survivor] who is protected from that person's acts under the domestic or family violence laws of the jurisdiction" (para. 2). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020a) defines intimate partner violence (IPV) as "physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse" (para. 1). These terms are often used interchangeably but may have state-specific implications in statistical considerations. Men may be excluded from the incidence or prevalence numbers in some states, which may require further exploration into the severity of the numbers (CDC, 2020a). The CDC (2019c) further defines SV as “sexual activity when consent is not obtained or not freely given” (para. 1).

In April 2018, the Office on Violence Against Women's website announced a change in the description of DV to focus only on the criminal aspects of DV. The former description included verbal abuse, economic abuse, and other forms of abuse that are common but not necessarily illegal (National Coalition Against Domestic Violence [NCADV], n.d.). While various states define domestic relations and penalties differently, there are broad definitions that may include or exclude intimidation, emotional abuse, harassment, or stalking (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2019). Further terminology includes trauma, which is "an emotional response to a terrible event such as an accident, rape, or natural disaster" (American Psychological Association [APA], 2019). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA, 2014) defines trauma using its three components, the three Es. These are the event, the experience of the event, and its effect (SAMHSA, 2014).

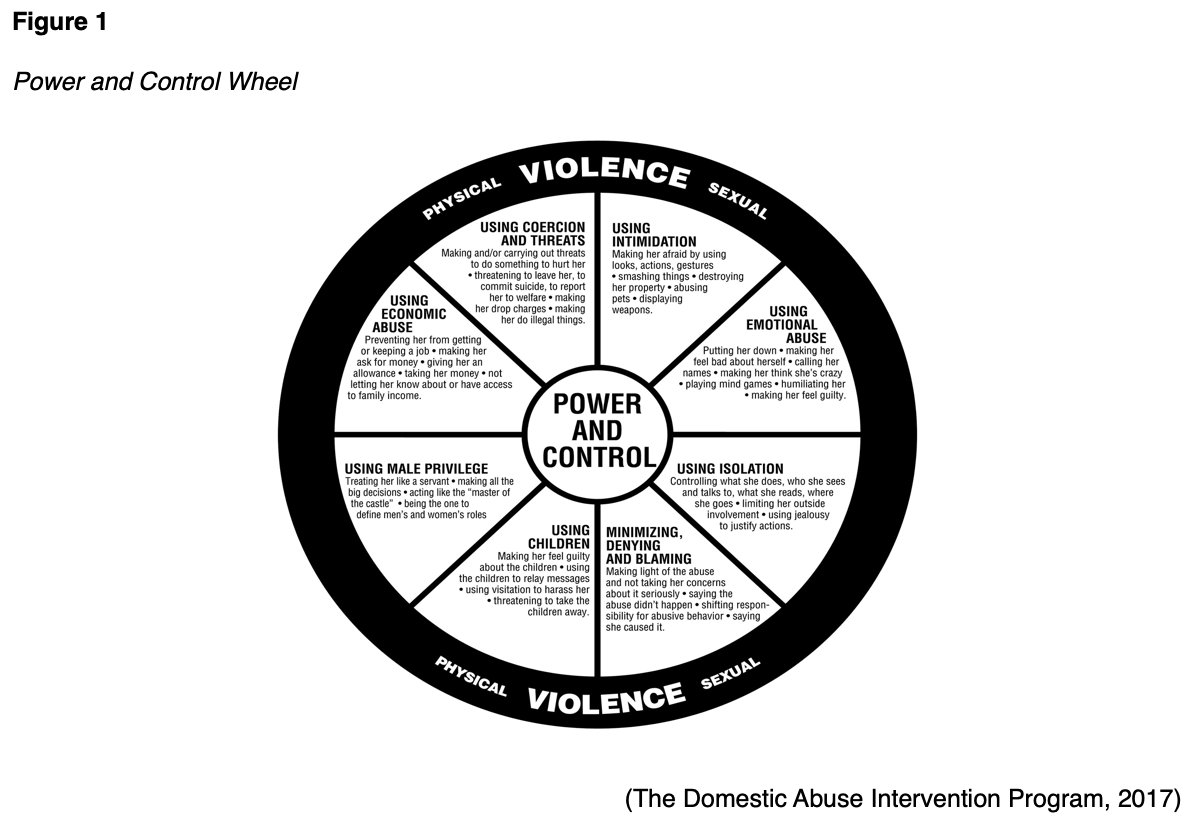

The National Resource Center for Domestic Violence (n.d.) views the element of controlling the victim as central to understanding DV. Whether the control is physical, emotional, mental, sexual, or financial, it leads to a lack of access for the survivor to resources, services, emotional and social support. Control tends to increase in intensity and frequency over time unless accountability from the abuser is achieved (National Resource Center for Domestic Violence, n.d.). Emergency room physicians in Duluth, Minnesota, created a Power and Control Wheel that identifies the ways that abusers control and dominate their partner (see Figure 1). This wheel can be used to better understand how perpetrators exert control and how caregivers can effectively intervene. The inner portion contains subtle, continuous ways that the abuser intentionally maintains control over their partner, either by economic means, intimidation, emotional abuse, isolation, coercion and threats, male privilege, or via mutual children. The wheel also includes common coping mechanisms for abusers, such as minimizing the abuse (indicating that it is normal or not significant), denying that the abuse occurs, or blaming the partner’s behavior for causing the abuse. This tool can be used to train healthcare staff to better understand the underlying patterns often seen in IPV (The Domestic Abuse Intervention Program, 2017).

Cultural Views of Domestic Violence

Throughout history, women and children have fulfilled different roles in society as compared to their male counterparts. Various cultures further view a woman's role in different ways from a man's. For instance, in certain cultures, if a woman spent too much money or was found to be unfaithful to her husband, he had the right to execute her. Men were permitted to sell their wives or children into slavery to pay off debts (Criminal Justice Research, n.d.). Some historical civilizations viewed women as possessions that belonged to their husbands, and physical beatings were not uncommon. Early English law appears to have dictated to men how to beat their wives; the phrase "rule of thumb" is derived from a law permitting men to beat their wives with sticks no more than "thumb-sized". A 16th-century Russian code suggested that a wise man would not hit his wife in the face or ears as she could become deaf or blind and be unable to care for him in the future (Tasbiha, 2017). Religious views may further add to the potential for violence against women; biblical passages demand for a wife to obey her husband and demonstrate submissiveness. Even today, judges in America may still opt to send families to counseling rather than suggesting resources to assist the survivor in separating themselves from an abusive relationship. Due to the fear of social stigma, many survivors hide the violence within their relationships, which can lead to serious health concerns, including death (Rakovec-Felser, 2014). While many of these traditional roles and behaviors may be viewed as antiquated and components potentially contributing

...purchase below to continue the course

There is a correlation between violence in our communities and DV or SV. Many of the mass shooting perpetrators have histories of DV toward family members. We regularly hear of government leaders or those in power being accused of sexual abuse, misconduct, or violent acts against women. Many children are exposed to television shows, movies, and video games that display or encourage acts of violence. This can lead toa public that is largely desensitized to the violence occurring in our communities without awareness of the consequences (Rakovec-Felser, 2014).

Historically, anger has been suspected as a rationale for abuse, and many abusers will cite anger as an impetus. However, studies agree that anger is not the basis of abuse as abusers often direct their actions toward the victim but can typically turn the rage on and off when in the presence of others (Cohodes et al., 2016).

Incidence and Prevalence

The NCADV reports that an average of 20 people experience physical IPV every minute, which equates to over 10,000,000 abuse survivors annually (NCADV, n.d.). In the U.S., one in every four women and one in every ten men are survivors of contact sexual violence (includes rape, being forced to penetrate, sexual coercion, or unwanted sexual contact), physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime. Ten percent of American women and 2% of men experience stalking by an intimate partner. One in five women and one in seven men endure severe physical violence (includes hitting with a fist or hard object, kicking, pulling hair, slamming into objects, choking, suffocating, beating, burning, or wounding with a knife or gun) during their lifetime (CDC, 2020a). Before the age of 18, 8.5 million women experience their first rape and 3.5 million are stalked, while 1.5 million men are forced to penetrate and 1 million experience stalking. A clear understanding of the significant number of survivors of DV can help the healthcare provider to recognize the prevalence and elucidate the possibility of survivors in their care (CDC, 2016).

Survivors are left with residual negative consequences, including injuries that require medical services, fear and anxiety regarding their safety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), chronic medical conditions, or death (CDC, 2020a). More than 50% of female survivors and almost 20% of male survivors of severe physical violence report concern for their safety, symptoms of PTSD, and feelings of fear. (CDC, 2016). Up to 72% of murder-suicides in the US involve an intimate partner, and 94% of victims are female. Furthermore, up to 20% of intimate partner homicides involve additional victims who attempted to help the victim, such as family members, friends, neighbors, law enforcement responders, or even bystanders (NCADV, n.d.). Long-term effects may include decreased quality of life, low self-esteem, mental health conditions, addiction, attempted suicide, unplanned pregnancy, child abuse, and witness abuse (ACOG, 2019).

The ACOG (2019) defines IPV as a "significant yet preventable health problem that affects millions of women regardless of age, economic status, race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or educational background" (p. 1). Women reporting IPV also fear being infected with an STI by their partners. While partner treatment is recommended, the healthcare provider should determine if there is an increased risk of IPV and avoid partner notification if deemed unsafe. As many as 20% of women seeking care at family planning clinics that report a history of IPV also report pregnancy coercion, and 15% report birth control sabotage that led to unintended or unwanted pregnancies (p.2). Over 320,000 pregnant women are abused in the United States each year. IPV of pregnant women has been linked to poor pregnancy weight gain, tobacco use, and anemia, leading to low birth weight, preterm delivery, fetal injury, placental abruption, and stillbirth. IPV is linked to severe injuries to women during the postpartum period and beyond, including acute injuries to the head, face, breasts, genitalia, and abdomen, or more non-acute symptoms such as chronic headaches, sleep and appetite disturbances, chronic pelvic pain, urinary frequency or urgency, irritable bowel syndrome, sexual dysfunction, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), or recurrent vaginal infections. The violence may continue to escalate during the postpartum period leading to homicide (ACOG, 2019).

Approximately $8.3 billion and 250,000 hospital visits are attributed to DV and SV annually (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2019, p. 2). The lifetime economic cost is estimated at $3.6 trillion, including medical services, lost productivity from work, criminal justice, and other costs (CDC, 2020a).

Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

Individual risk factors for IPV perpetrators include:

- being a survivor of physical or psychological abuse (one of the highest predictors of perpetration)

- low self-esteem

- low income

- low academic achievement/verbal IQ

- young age

- aggressive or delinquent behavior as a youth

- substance abuse

- depression or mental health conditions

- anger/hostility

- lack of nonviolent problem-solving skills

- antisocial or borderline personality traits

- poor impulse control

- a prior history of being physically abusive to others

- social isolation or having few friends

- unemployment

- emotional dependence or insecurity

- a belief in strict gender roles, hostility towards women, or attitudes that accept or justify IPV

- an unplanned pregnancy

- a desire for power and control (CDC, 2020c, para 4)

Relationship risk factors for IPV include:

- marital conflict, tensions, instability, or negative emotions within the relationship

- jealousy, possessiveness, dominance, and control of the relationship by one partner over the other

- economic stress

- unhealthy family relationships or interactions

- association with antisocial or aggressive peers

- parents with less than a high school education

- a lack of social support

- a history of experiencing poor parenting/physical discipline or witnessing IPV between parents as a child (CDC, 2020c, para 5).

The CDC identifies the following community risk factors for IPV:

- poverty,

- low social capital (a lack of institutions, relationships, or norms that shape the community's interactions),

- poor neighborhood support or cohesion.

- weak community sanctions against IPV (such as neighbors that will not intervene when they witness violence)

- high density of places that sell alcohol (CDC, 2020c, para 6).

Societal factors that can lead to IPV are:

- traditional gender norms and gender inequality

- cultural norms that support aggression toward others

- societal income inequality

- weak health, educational, economic, and social policies/laws (CDC, 2020c, para 7).

Protective Factors for IPV

Relationship factors that reduce the risk of IPV include high-quality friendships and societal support. Community factors that further deter IPV include neighborhoods with a collective cohesiveness and support that is willing to intervene for the common good. Further protective factors include the coordination of resources and services among community agencies (CDC, 2020c). A systematic review that explored risk factors and protective factors for IPV demonstrated that being older and married were considered protective factors. Higher education was also mentioned as a possible protective factor to IPV (Yakubovich et al., 2018).

Special Population Groups

Adult women are frequently the survivors of DV and SV. However, special populations also at risk include children and adolescents, mentally or physically disabled or ill individuals, older adults, women of color, immigrant women, members of the LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer/questioning) community, homeless individuals, low socioeconomic status (SES), rural, or male patients can be victims as well (CDC, 2020a; Petrosky et al., 2017; Rakovec-Felser, 2014).

Children

About one in seven children experience abuse and neglect each year in the United States. In 2008, the CDC attributed over $124 billion to the economic burden of child maltreatment. Children can be survivors of neglect or physical, sexual, or emotional abuse. This can be perpetrated by a parent, caregiver, teacher, clergy, or any other person of authority over the child (CDC, 2019b).

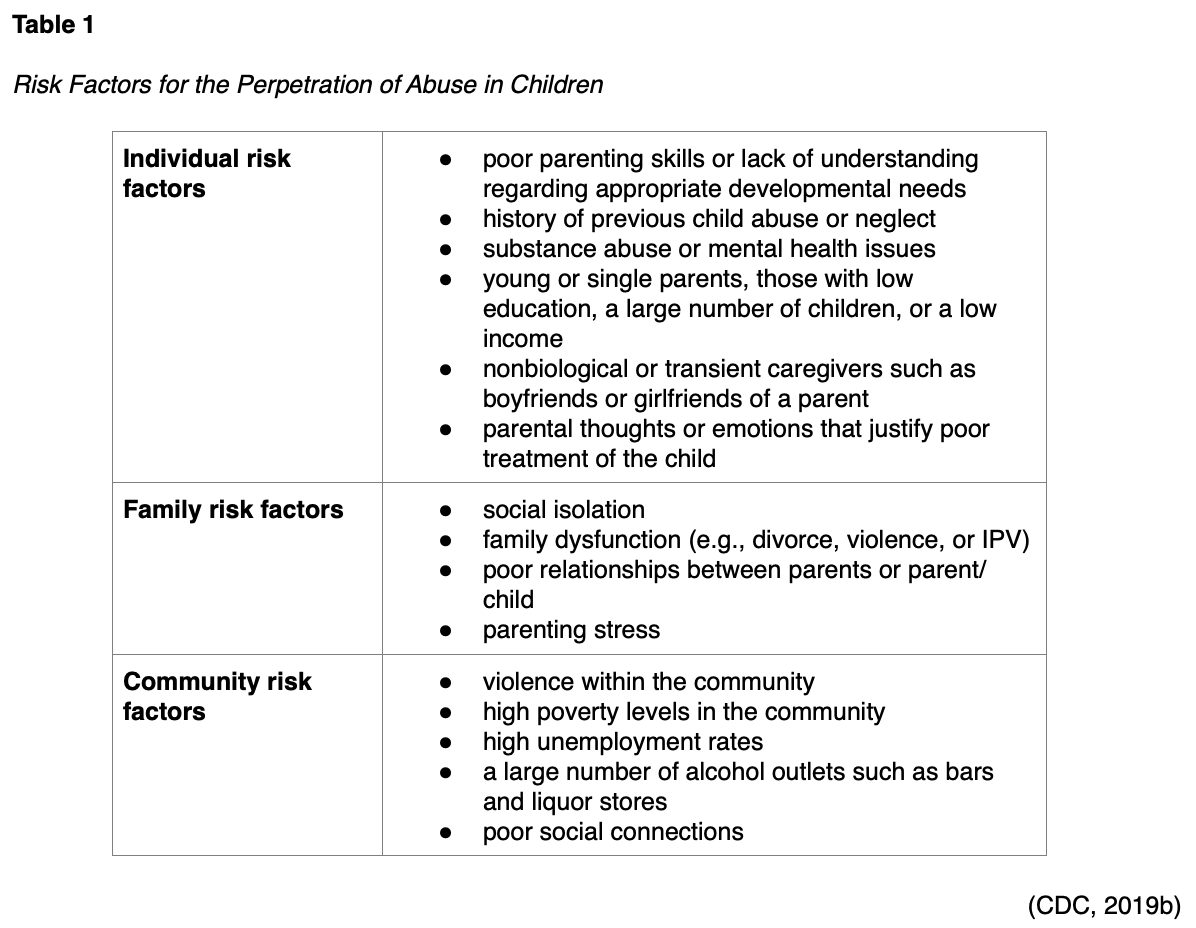

Individual risk factors for child abuse are related to victimization, including age and special needs. A child under four years of age is at higher risk than an older child as they may be unable to identify or report the events. Conditions such as autism, developmental delays, and chronic physical or mental illnesses increase the caregiver burden and therefore increase the risk of abuse or violence. Children living in poverty have five times the risk of abuse than children in higher socioeconomic environments (CDC, 2019b). Table 1 categorizes additional risk factors for this age group:

Protective factors for children against abuse or neglect include:

- supportive family networks or social networks

- basic needs met

- strong parenting skills

- stable family relationships

- child monitoring and household rules

- parental employment

- adequate housing

- access to social services and healthcare

- adults outside the family who serve as role models or mentors

- supportive caregivers in the parent's absence

- community support that works to prevent abuse (CDC, 2019b).

The goal is to prevent abuse and neglect before it happens. Among the preventative techniques is to strengthen economic support to families through a family-friendly work policy or household financial security. Social norms and educational campaigns that focus on positive parenting and coaching are effective. Children should have quality care and education during their toddler, preschool, and early elementary years. These can be encouraged through state licensing and accreditation of daycare centers and early childhood programs. Initiatives such as early childhood programs and home visits can promote parenting skills and healthy child development. Finally, pediatricians and primary care providers should monitor for and intervene in high-risk situations where future abuse and neglect are suspected to minimize the effects and possibly avoid future concerns (CDC, 2019b).

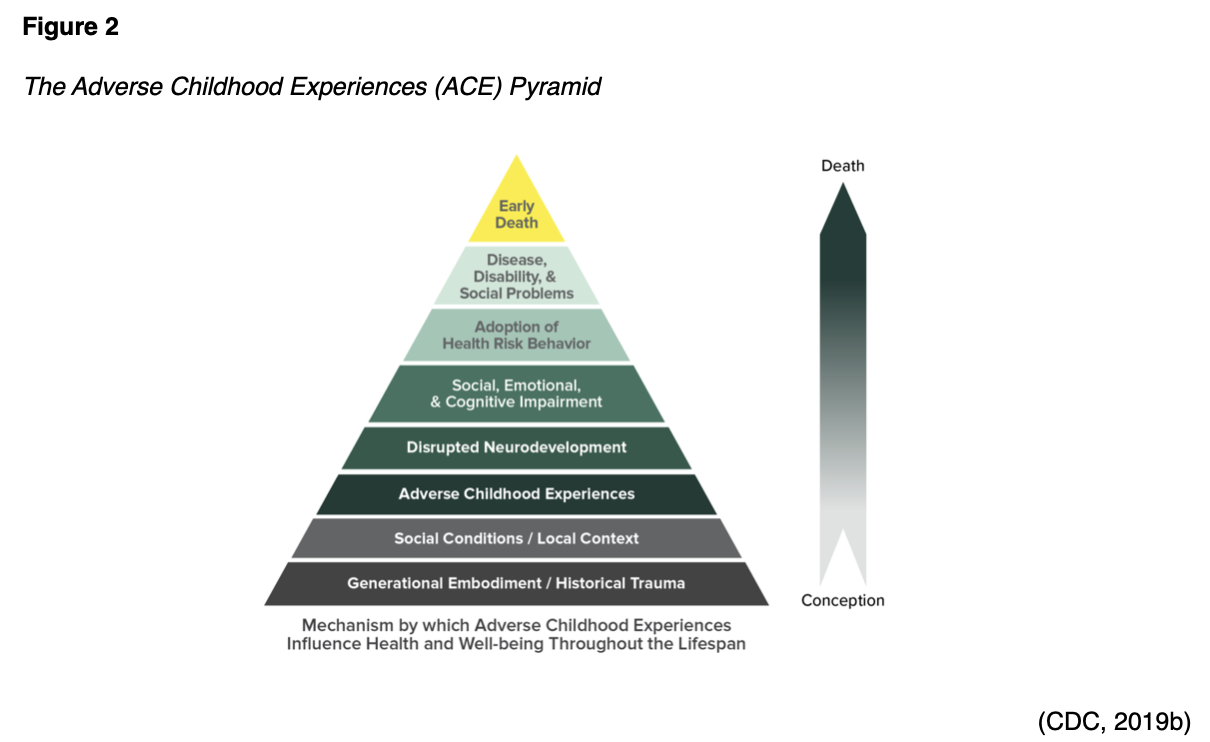

Child abuse and neglect leave a long-lasting impact on survivors; Figure 2 highlights the potential concerns with adverse childhood experiences (ACE) over a lifetime:

Abuse and neglect cause physical changes in children's brains. Poor impulse control, an inability to experience pleasure, or antisocial behaviors can stem from previous abuse and neglect. A child that lives in an unstable environment with constant stress or violence is more likely to develop learning disabilities, anxiety, or even physical illness, including cancer, diabetes, and early death. Children exposed to violence are more likely to have poor school performance and develop substance abuse disorders as well as a variety of emotional and physical health concerns. They may have difficulty with interpersonal relationships with peers in the present and in the future (Bellis et al., 2017).

Studies have shown a direct correlation between psychopathic traits of adults and exposure to violence as a child (Bellis et al., 2017; Dargis & Koenigs, 2017). Exposure to violence in children (under the age of 18) was assessed during the National Survey of Children's Exposure to Violence, or NatSCEV, a joint effort of the CDC and the U.S. Department of Justice. Most (67.5%) of respondents had witnessed some form of violence or abuse directly or indirectly in the last year (when a crime was included in the definition of violence or abuse). Even more troubling was that 41% had multiple exposures in the past year, which could be trauma-inducing if not identified and properly addressed. Up to 10% of the respondents reported six or more direct exposures in the last year, making them highly vulnerable to adversities and distress, or "polyvictims". Exposure to violence can cause many of the same emotional and psychological effects as direct maltreatment if not managed appropriately. NatSCEV found that exposure to violence increased the risk of other types of violence/maltreatment as well (Finkelhor et al., 2015).

Adolescents

Violence occurring in the youth and adolescent population varies from that of most DV and SV. Bullying is reporting by one in five high school students, and social media bullying is reported by one in seven in the past year. About 14 adolescents are victims of homicide each day, and 1,300 are treated at hospitals for non-fatal assaults and subsequent injuries. More than $21 billion are spent each year on medical and related costs due to violence among adolescents (CDC, 2019d).

Youth violence can start early with bullying and physical aggression. While children as young as toddlers can be aggressive, they are expected to learn alternate ways to manage their emotions before entering school. Early childhood risk factors for later violence among adolescents include impulsive behavior, poor emotional control, and lack of problem-solving skills. These children may be survivors of DV, SV, or chronic stress that can lead to altered brain development and lead to a cycle of abuse of others (CDC, 2019d).

Of particular concern among the adolescent population are young girls. Teen dating violence can include physical, sexual, psychological, or emotional abuse by an intimate partner and may involve stalking. According to the CDC (2020b), 1 in 11 female and 1 in 15 male high school students report that they have experienced dating violence in the last year. One in nine females and 1 in 36 males report sexual dating violence that occurred in the last year (CDC, 2020b). Peer pressure can accelerate violence in this group, in combination with a social environment that may influence teens to remain in unhealthy relationships to fit in socially. Adolescents are more likely to have inadequate coping skills and may revert to physical aggression or emotional abuse when presented with conflict (Black et al., 2017).

The CDC (2019d) offers a technical package on their website entitled A Comprehensive Technical Package for the Prevention of Youth Violence and Associated Risk Behaviors. Figure 3 outlines these strategies briefly.

There effects related to youth violence are lifelong, including adverse health and well-being, future risk of violence in relationships, victimization, smoking, substance abuse, obesity, high-risk sexual behavior, depression, academic difficulties, school dropout, and suicide. Youth identified as survivors or perpetrators of abuse should be assessed for previous violence and abuse by others (CDC, 2019d; Cohodes et al., 2016).

Mentally or Physically Disabled or Ill

Disability affects more than 56 million Americans and is associated with a higher risk of violence or victimization than the general population. People with disabilities have a greater than 50% chance of IPV over their lifetime; reasons cited for this include physical dependence on an intimate partner, higher levels of poverty, social isolation, and perceived vulnerability by their perpetrators. In a 12-month study by Breiding and Armour (2015), women with a disability reported a 23.8% prevalence of rape, sexual violence other than rape, physical violence, stalking, and psychosocial aggression while men had a 20.1% prevalence of the same (except for rape). The male participants did not report any cases of rape during this study (Breiding & Armour, 2015).

A survey by the Spectrum Institute’s National Disability and Abuse Project found that over 70% of the respondents with disabilities experienced some form of mistreatment by an intimate partner, family member, caregiver, acquaintance, or stranger. Verbal or emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, and financial abuse were reported, with less than one-third of these being reported to the police. Abuse among the disabled may also include unwanted sexual contact, threats, intimidation, withholding medications, physically harming service animals, isolation, withholding of necessary physical accommodations or assistive devices, or financially exploiting/misusing the victim's finances Within this group, children and adolescents with autism, developmental delays, or other disabilities are at increased risk of victimization (NCADV, n.d.).

Usta and Taleb (2014) cite a systematic review and meta-analysis that concluded individuals diagnosed with mental illness, especially women, are predisposed to abuse. This review looked at 41 studies and determined that depression, anxiety, and PTSD all increase the risk of being a victim of IPV as an adult (Usta & Taleb, 2014). A further concern for individuals with mental illness is the risk of abusing others. For instance, someone with an antisocial personality has a lower tolerance for distress and may have psychopathic traits that could lead to an increased risk of violence towards partners or others. Healthcare workers should recognize the inherent risk associated with mental health disorders, as one in eight mental health patients report DV within the past year. Mental health disorders predispose the individual to violence both physically and emotionally, both as a survivor and perpetrator (Brem et al., 2018).

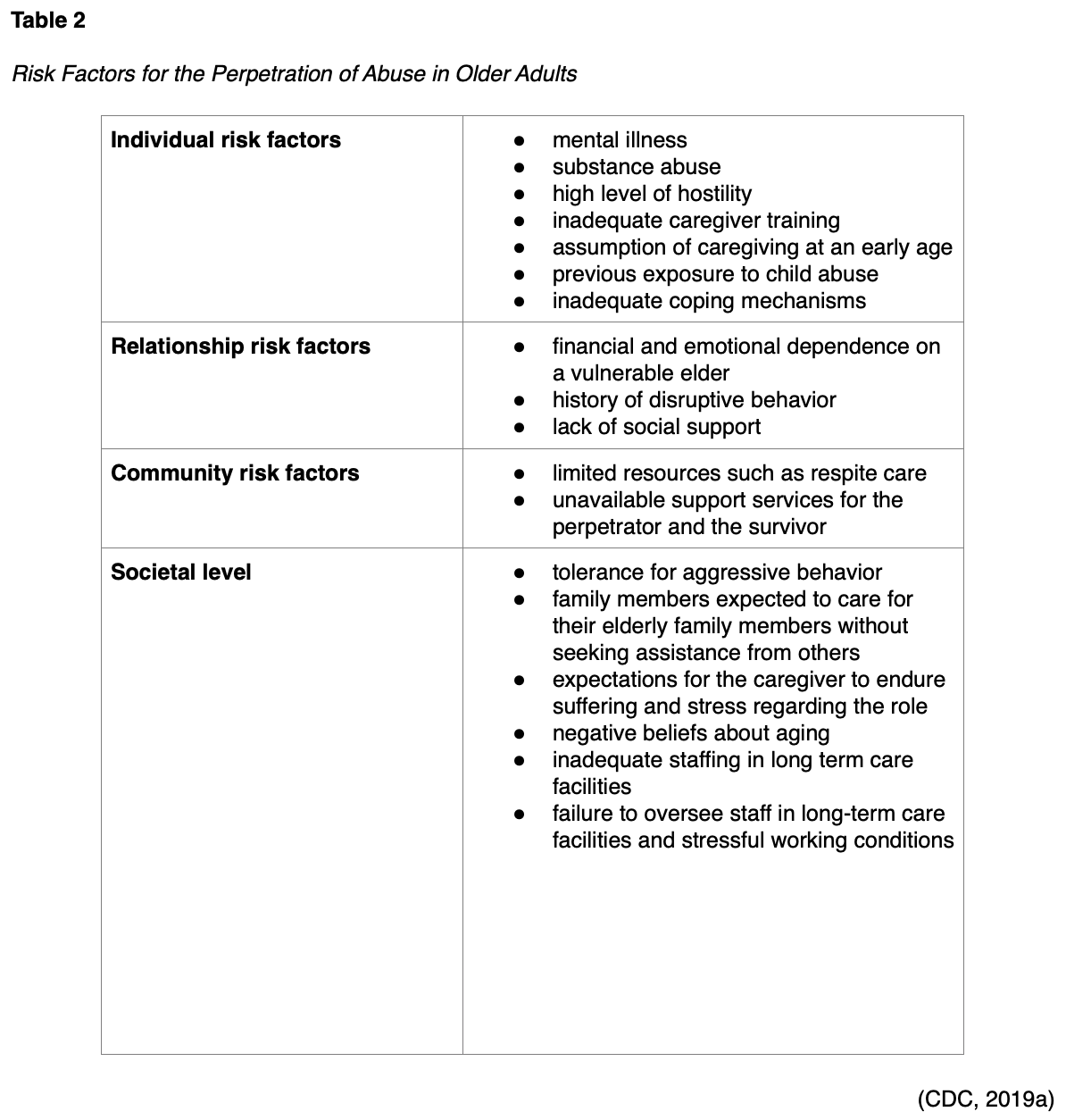

Older Adults

Elder abuse is defined as an "intentional act or failure to act by a caregiver or another person in a relationship involving an expectation of trust that causes or creates a risk of harm to an older adult…60 years of age or older". Approximately one in ten Americans over the age of 59 experience elder abuse or neglect annually. For every case reported, research suggests that an estimated 20 or more cases are unreported (CDC, 2019a). Risk factors for a perpetrator may be individual, relational, community, or societal in origin. The healthcare provider should understand the risk factors to identify opportunities for prevention. Table 2 lists the risk factors for perpetration in this age group:

Protective factors for elder abuse include the individual having strong relationships with multiple people and avoiding isolation at the relationship level. Community protective factors support the coordination of resources and services that serve the elderly and their caregivers and effective monitoring systems within institutional settings. Policies and procedures, staffing, and oversight within a long-term care facility can decrease the opportunity for neglect or abuse. Regular visits by family members, social workers, and volunteers help to decrease opportunities for abuse as well (CDC, 2019a).

The consequences of elder abuse are physical and psychosocial. While minimal studies have considered the consequences of elder abuse, some aspects are agreed upon by experts. These include physical injuries such as bruises, broken bones, pressure sores, lacerations, or dental problems; persistent pain; nutrition and hydration issues; sleep problems; increased susceptibility to illness including STIs; worsening of previous health conditions; or increased risk of death. Psychological effects can range from fear and anxiety to depression or PTSD (CDC, 2019a; Indu, 2018). While important for the healthcare provider to understand the signs and effects of abuse in the elderly, it is crucial for the nurse to help create awareness among the elderly population regarding their legal and social support opportunities and assist them in addressing situations where their safety is questionable. Many times, the older adult does not seek help and fears retaliation or worsening conditions. A culture that has zero-tolerance for abuse or neglect, along with ongoing assessment, can minimize the number of elderly abuse cases in the United States (Indu, 2018).

The CDC recommends that healthcare providers listen carefully to older adult patients and their corresponding caregivers to accurately assess challenges and needs. Healthcare providers should be aware of the indications of abuse, and how these differ from the normal aging process. Isolated older adults with less of a social support network are at increased risk and require more frequent assessments/check-ins. Caregivers should be supported by recruiting friends, family members, and connecting them with local relief/support groups or adult day care programs in the area for respite. Caregivers should be cognizant of their own emotional and mental well-being, with active participation in counseling and other self-care activities. Any substance abuse should be identified early and managed aggressively, as this increases the risk of violence and abuse (CDC, 2019a).

People of Color and Immigrants

The effects of IPV are disproportionately borne by women of color in the United States, including immigrants. Native American and Alaska Native (NA/AN) women report an IPV prevalence of 46%, while non-Hispanic Black women report an IPV prevalence rate of 43.7%, according to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey. Hispanic women report an IPV prevalence rate of 37.1%. While all women who are victimized by IPV report multiple health outcomes, these are found in higher rates among women of color. This may include fibromyalgia, joint disorders, hypertension, stomach ulcers, digestive problems, vision and hearing problems, memory loss, traumatic brain injury, depression, PTSD, low self-esteem, and suicidality. Survivors of sexual violence may develop vaginal and anal tearing, sexual dysfunction, pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, pelvic inflammatory disease, cervical neoplasia, and STIs such as HIV at higher rates than those not exposed to violence. Women of color and immigrant women are more likely to live in poverty, have lower levels of education, and have less access to healthcare, which limits their ability to manage the adverse effects and complications of IPV (Stockman et al., 2015).

As many as 34% of NA/AN reported rape or sexual assault during their life, which is almost double the rate for the rest of the US population. However, the accuracy in reporting the prevalence of DV/SV within the native community is often questioned, as data is not officially gathered by federal or Indian agencies (Hardy & Rice, 2016). Homicide is one of the leading causes of death for women over 44 years of age, and most are by intimate partners. NA/AN women experience the highest rate of homicide at 4.4 and 4.3 per 100,000 population, respectively. Over half of these murders are IPV-related, and over 11% were victims of IPV in the months preceding their deaths (Petrosky et al., 2017). Women living on native reservations often have unique legal barriers due to the laws governing their territories and the rights of their residents (Hardy & Rice, 2016). As many as 70% of NA/AN women report violence at the hands of non-native men (Potera, 2014).

Most of the abuse towards native women and children relates to historical victimization. The repression of NA/AN has limited their economic resources and caused a dependency through retracting tribal rights and sovereignty. Both groups suffer from the normalization of violence and internal oppression. Many perpetrators are found to use alcohol or drugs before violent events. A higher rate of substance abuse is often correlated with community issues, including repression, tribal laws, lack of medical or social support, and a fundamental lack of trust outside the NA/AN community. These factors can lead to alcohol and substance abuse, mental anguish, and suicide (Hardy & Rice, 2016).

Risk factors for DV and SV in these populations include low SES, unemployment, gender, cultural affiliation, substance abuse, relationship status, history of exposure to violence, and previous childhood experiences. Residual effects of the abuse include depression, anxiety, chronic pain, substance abuse, promiscuity, suicidal ideation, decreased communal cohesion, and cardiovascular disease. Mental health resources on tribal lands are insufficient and substandard in quality. Poor access to care during a crisis and a lack of multicultural competency are pervasive concerns in mental healthcare among the native population. As an example, while there are over 500 tribes within the US, only 26 native-specific shelters exist. Healthcare providers and mental health practitioners should work to eliminate barriers for those who require mental health services and attempt to break the cycle of abuse through community-driven efforts. Interventions should focus on all four parts of the Native American Medicine Wheel: mental, spiritual, physical, and emotional. Several studies indicate a need for increased focus on spiritual exercises while working with NA/AN women. A multi-modal approach optimizes the care for survivors. Mental health, legislative changes, creating a trusting environment through culturally competent care by healthcare providers, and developing patient-centered approaches may provide the most significant outcomes. There is a need for more culturally specific shelters, along with a higher awareness of the significance of DV and SV in the NA/AN populations (Hardy & Rice, 2016).

Immigrant women are more likely to experience IPV. As many as 48% of Latina women report an increase in IPV after immigrating to the U.S., and studies indicate a prevalence rate for Asian immigrant women at 24-60%. Language barriers, lack of knowledge about legal rights or processes, and the stress of relocating to a foreign country all contribute to this trend (Stockman et al., 2015). Individuals from various cultural backgrounds may view DV and SV differently and may not recognize certain behaviors as abusive. Immigrants may also be hesitant to report DV or SV due to fears of deportation. These individuals need culturally appropriate care that is sensitive to accessibility issues, racism, language barriers, and acculturation. Healthcare providers can help to educate immigrants that they have a right to live free of abuse and that DV is illegal in this country regardless of the person's immigration status or country of origin (ACOG, 2019; National Domestic Violence Hotline, 2019).

LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bi-Sexual, Transgender, and Queer/Questioning)

According to the NCADV (n.d.), over 43% of gay and 61% of bisexual women have experienced rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime; these statistics are in contrast to just over 35% of heterosexual women. Rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner was reported by 26% of gay men and 37% of bisexual men in comparison to 29% of heterosexual men. Only one-quarter of these assault survivors contacted the police even with life-threatening attacks (NCADV, n.d.).

Transgender individuals are more likely to experience IPV in public than cisgender individuals. Black and African American LGBTQ individuals are more likely to experience IPV than LGBTQ individuals that do not identify as Black or African American. White LBGTQ individuals are more likely to experience sexual violence than their counterparts who do not identify as white. Finally, LGBTQ individuals on public assistance such as welfare or food stamps are more likely to experience IPV than their peers who are not on public assistance (NCADV, n.d.). The National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP, 2016) noted that IPV in the LGBTQ community exists in concert with the broader bias towards this community as a whole. This is more pronounced in multiple vulnerabilities, such as LGBTQ individuals of color, disability, or undocumented immigrants.

Violence among this group includes physical violence, verbal harassment, threats and intimidation, isolation, online or telephone harassment, stalking, sexual violence, or economic/financial violence. As many as 27% of survivors of IPV were denied access to emergency shelters in 2015. The most commonly reported reason was a barrier related to their gender identity. Police are often reported to be hostile or indifferent to the LGBTQ survivor's report of IPV, and up to 31% noted the erroneous arrest of the victim rather than the perpetrator (NCAVP, 2016).

Culturally appropriate care for the LGBTQ community is essential to meet their unique needs. Barriers to care, vulnerabilities, and lived experiences can create a culture that diminishes the group's needs. To prevent IPV among the LGBTQ community, lawmakers should fund specific prevention initiatives. Education should focus on the current problems the LBGTQ community is facing and encourage awareness of the issue within healthcare organizations and providers. Early intervention and preventative programs, along with campaigns against IPV, can change the outcomes for this vulnerable population (NCAVP, 2016).

Homeless Individuals

Domestic violence was cited as the primary cause of homelessness in 17% of cities nationwide (APA, 2016). Low income, unemployment, economic stress, and poverty are also known risk factors for IPV perpetrators (CDC, 2020a). Between 22-57% of women who are homeless report that the immediate cause of their homelessness is DV, while this number increases to more than 80% among mothers with children. Of all DV survivors, 38% will be homeless at one time. A Florida study of 800 women who were homeless found that they are two to four times more likely to experience violence of any type. Studies have identified a positive correlation between a history of food and housing insecurity in the last year and a history of rape, physical violence, or stalking in the last year. Trauma has been found to frequently "precede and prolong" homelessness for children and families (Family & Youth Services Bureau, 2016).

Socioeconomic Status and Rural Communities

SES is a term that includes perceived social status, income, and educational level. Youth from lower SES backgrounds have a higher frequency of exposure to violence in the home and community, as well as a higher likelihood of detrimental effects from this exposure. A child with lower SES is more than twice as likely to experience three or more violent exposures as compared to higher-SES children. Exposure to violence can then conversely affect an individual's subsequent potential to maintain employment, as survivors of IPV frequently lose their jobs, are made to resign, or undergo high turnover. This is immediate but may also persist for some time after the abuse ends. Low income is also an independent predictor for neglect in older adults. Violence prevention programs should be developed that target segregated, low-SES communities by alleviating unemployment and poverty, increasing community participation, improving housing conditions, and improving access to services to lower the community-wide DV and SV rates (APA, 2016).

The effects of DV and SV in rural communities is directly related to limited access to resources/services, distance/transportation barriers, a lack of acceptance of alternative lifestyles, and a relative paucity of shelters and affordable housing. Survivors in small towns are less likely to report abuse if they or their abuser are familiar with their healthcare providers and law enforcement officers, citing concerns about not being believed, breaches in confidentiality, tarnished reputation, or escalated violence/retaliation. Only 41% of violent crimes in rural areas are reported, which artificially reduces the data on these crimes. In order to better understand DV and SV in rural areas, the National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services requested that a geographic variable be added to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey from the CDC to elucidate the level of urbanization (Rural Health Information Hub, 2018).

Male Victims/Survivors

There are very few studies that focus on the male survivor of DV or SV, and male victimization is under-reported, under-treated, and under-recognized by healthcare professionals. "Abuse is overlooked in male survivors and may be due to prevailing cultural norms, myths, assumptions, stigma, and biases about masculinity" (Elkins et al., 2017, p. 116). Within any vulnerable group, men or women may be the victim; however, there are specific instances and situations related to men who experience DV and SV. This violence can be between family members, intimate partners, or former partners. The abuse can be psychological, physical, sexual, financial, or emotional. As many as one in seven men report being a survivor of DV or SV during their lifetime. Male survivors may not report the abuse, feeling that they are isolated in this type of experience and embarrassed by it. Unfortunately, males are less likely to be suspected of being a survivor, less likely to seek help, and less likely to be believed when reporting abuse than their female counterparts. Even when healthcare providers recognize abuse among males, the survivor may not recognize it as abuse (Elkins et al., 2017; Peate, 2017).

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK works to address DV and SV. NICE suggests that all of the work towards the prevention and care of DV/SV survivors should be gender inclusive. This organization further explored the problem of male DV and SV and found that men were vulnerable regardless of age, ethnicity, geography, or SES. NICE further encourages nurses to ensure that they are screening for DV and SV in the male population, providing resources and emergency support such as housing for males and their children as appropriate (Peate, 2017).

There are significant consequences for the male survivor of DV and SV. The effects may be emotional, behavioral, or social. Sexually abused males have higher rates of PTSD, substance abuse, and suicide. High-risk sexual behavior, fighting, and dating-violence are also common among survivors of SV. Perpetrators of male DV and SV may be male or female and occur regardless of sexual orientation. Men are more likely to report sexual abuse where the perpetrator is a family member; however, most SV in males is from non-family members. Given the low rates of self-disclosure of DV and SV among males, healthcare providers must be trauma-informed and do their part to create a culture that gives male survivors the same considerations as female survivors. However, gender-specific care should be administered to create a safe and supportive environment for male survivors of DV and SV (Elkins et al., 2017).

Prevention of DV/SV

According to the CDC (2020a, 2020b), the key to IPV reduction is prevention. In both teens and adults, they suggest “teaching safe and healthy relationship skills, engaging influential adults and peers, disrupting the developmental pathways that lead toward a cycle of family violence, creating protective environments, strengthening economic support for families, and finally supporting survivors to increase safety and lessen harms” (p. 2). The details of these steps for prevention are shown in Figure 4 (CDC, 2020a).

The CDC (2019e) also developed the Public Health Approach to Violence Prevention (PHAVP), which outlines four clear steps to prevent violence:

- define and monitor the problem

- identify risk and protective factors

- develop and test prevention strategies

- assure widespread adoption (CDC, 2019e)

Healthcare facilities can begin to adopt this approach through ongoing surveillance and reporting to the appropriate agencies. The first two steps focus on defining the problem by sharing statistics and understanding the risk and protective factors. PHAVP can create a trauma-informed culture that readily identifies survivors and patients at risk for victimization. The goal of violence prevention is to decrease the risk factors and increase protective factors. In the third step, strategies are explored and defined to develop the optimal interventions to reduce or ultimately prevent violence. Finally, in step four, strategies that have been proven successful are shared within the healthcare communities, and broad adoption of best practices takes place. Ongoing monitoring, assessment, and evaluation are necessary to stay ahead of changes in trends or identify opportunities to improve interventions (CDC, 2019e).

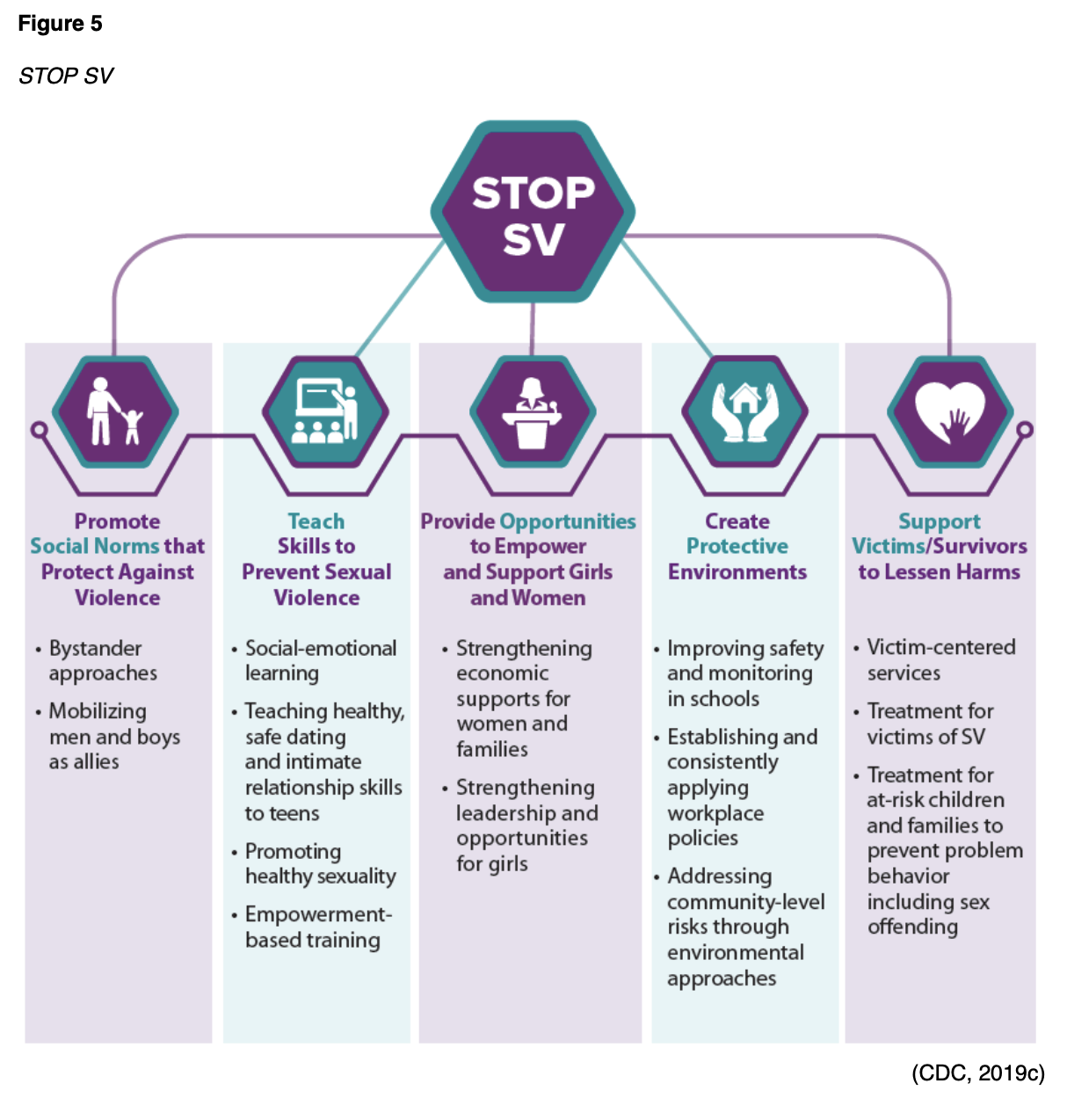

In order to prevent sexual violence, the CDC developed the acronym STOP SV, the components of which are depicted in Figure 5 (CDC, 2019c).

Creating a culture of trauma-informed care or practice (TIC or TIP) can facilitate early recognition and intervention to decrease victimization (Wilson et al., 2015). The Center for Health Care Strategies (n.d.) describes TIC as shifting the focus to what happened to the survivor, as opposed to what is wrong with the survivor. They further explain that in order to care for the entire patient with a healing orientation, healthcare organizations and teams must develop a complete picture of a patient’s past and present life situation. If implemented optimally, TIC has the ability to improve patient outcomes, advance treatment adherence, reduce healthcare and social services cost, and promote healthcare provider/staff wellness. It must be adopted at both the clinical as well as the organizational level. TIC seeks to:

- realize the widespread impact of trauma and understand paths for recovery;

- recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in patients, families, and staff;

- integrate knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and

- actively avoid retraumatization (Center for Health Care Strategies, n.d., para. 2).

The SAMHSA (2014) defines TIC as including the four R's (Table 3):

The four Rs approach is in concert with the CDC's four steps towards violence prevention. Either or a combined approach, applied consistently, will create a trauma-informed culture and organization that meets the needs of DV/SV survivors (CDC, 2019e; SAMHSA, 2014).

Common Indicators of DV and SV

In order to identify patients potentially experiencing DV or SV, the healthcare provider must first be educated to recognize the signs and symptoms in all groups, including women, men, and all the vulnerable populations discussed in this module (Wilson et al., 2015). The following list of signs and symptoms are common indicators of abuse that the nurse and other healthcare providers should be watchful for when caring for patients:

- injuries that point to a defensive position over the face (bruises and marks on the inside of the arms, back);

- injuries to the chest and stomach, reproductive organs, and anus;

- illness or injuries that do not match the cause given;

- a delay in requesting medical care;

- injuries and bruises of various colors, indicating that they did not occur together;

- repeat injuries, or someone who is 'accident prone' and evidence of healed fractures on x-ray;

- ruptured eardrums;

- injuries during pregnancy;

- repeated reproductive health problems, such as repeat miscarriages, early delivery, STIs, vaginal discharge, or sexual dysfunction;

- psychological or behavioral problems;

- suicide attempts or signs of depression;

- repeat and chronic medical complaints, pelvic problems and pains, psychological diseases, chronic headaches (including migraines);

- repeatedly missing work, school, or social obligations without explanation;

- behavioral signs such as multiple visits seeking medical care, a lack of commitment to appointments, not displaying any emotion or crying very easily, an inability to undertake daily interactions, negligence, defensive positions, stilted speech, avoiding eye contact, discomfort in the presence of their partner, acting nervous or anxious, attempting to hide injuries with sunglasses, scarfs or outerwear, and animosity in body language (HelpGuide, 2019; Usta & Taleb, 2014).

If present, the abuser/partner may display extreme or irrational jealousy or possessiveness. Abusers may attempt to control the time spent with the provider or nurse by insisting on staying close to the patient and speaking on their behalf (Usta & Taleb, 2014).

Injuries may be of a physical nature, including bruises and fractures, which are quickly recognized by the nurse or healthcare provider. However, the abused individual may exhibit a wide range of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, reproductive, musculoskeletal, or central nervous system conditions; these are typically chronic in nature and less obvious to the caregiver. Mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety may be related to current or previous DV or SV (SAMHSA, n.d.). Survivors of DV or SV may present to their healthcare team with complaints of poor appetite, disturbed sleep, or mood disorder symptoms (Usta & Taleb, 2014). Warning signs of abuse may also include asthma, stress-related illnesses, anxiety/panic attacks, vague aches and pains, chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, bladder/kidney infections, joint pain, or muscle pain (HelpGuide, 2019).

Screening Tools

The primary role of healthcare providers is to recognize potential survivors of DV and SV, provide screening, and offer interventions and resources. In 2011, the Institute of Medicine recommended that IPV screening and counseling be included as core components of all women's health visits; this was further supported by the CDC (2014) and ACOG (2019). Various screening tools are available for the nurse and other healthcare providers, and there is no preference for a single instrument, but rather a consistent pattern of patient screening with an organizational culture of trauma-awareness.

The Humiliation, Afraid, Rape, Kick (HARK); Hurt/Insult/Threaten/Scream (HITS); Extended-Hurt/Insult/Threaten/Scream (E-HITS); Partner Violence Screen (PVS); and Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) are validated screening tools to assess for DM and SV. The HARK has four questions that assess for emotional and physical abuse in the past year. The HITS has four items that determine the frequency of IPV, and the E-HITS includes additional issues related to SV. The PVS has three questions that assess for physical abuse and the safety of the individual. The WAST assesses for physical and emotional IPV via a series of eight questions (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2019).

A concerted effort should be made to conduct screening for DV and SV in private, which may be difficult with children, disabled, and other vulnerable populations who depend on caregivers for transport and assistance within the healthcare system. Language barriers or other communication disabilities should also be considered, such as blindness or hearing impairment (Breiding & Armour, 2015; National Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence, 2017). Privacy allows the survivor to respond to screening questions without fear of retaliation. In addition to the tools, healthcare providers should assess for the physical and emotional signs of abuse. In addition to the screening and assessment by healthcare providers, the Health Resources and Services Administration Strategy to Address Intimate Partner Violence directs health centers across the country to build partnerships with local DV/SV programs; prepare by implementing new/updated policies to prevent, identify, and care for DV/SV survivors in partnership with local DV/SV programs; adopt the evidence-based intervention to educate patients on the connection between IPV and their health to promote wellness and safety; train providers/staff regarding the impact of DV/SV on health outcomes and how to assess/care for survivors of DV/SV; and evaluate and sustain progress through diligent quality improvement (National Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence, 2017, p. 3). Reciprocally, with partnerships in place, survivors of DV/SV who seek assistance at a local DV/SV program can then be connected with health clinic staff and resources to obtain the medical care that they may need. The evidence-based method for screening and brief counseling patients regarding DV/SV advocated in this program is the CUES intervention:

- Confidentiality- patients should be seen alone for at least of portion of their visit, and the healthcare professional’s limits of confidentiality should be disclosed prior to discussing IPV

- Universal education and Empowerment- discuss with all patients about health and unhealthy relationships and the effects of violence; at least two FUTURES’ safety cards should be given (one for a friend)

- Support- discuss a patient centered care plan to encourage harm reduction, make a warm referral to the local DV/SV program partner, and document the disclosure to follow up at the next visit (National Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence, 2017, p. 9).

Despite being asked directly by a healthcare professional about violence, women may choose not to disclose due to distrust or fear of subsequent violence. A study based on survivors’ advice suggests that the healthcare professional reduce the woman’s suspicions and stigma by explaining why they are asking. They also recommend creating a supportive and safe atmosphere and providing information and access to resources regardless of whether or not they disclose. The act of asking about IPV raises awareness, educates, and transmits compassion (National Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence, 2017).

Adolescents can be screened using the Conflict Tactics scale. This scale was developed in 1972 based on the conflict theory. It examines specific acts or events used in a conflict and considers that abusers are seeking power and control over the victim (Ronzon-Tirado et al., 2019).

Women of reproductive years have the highest prevalence of IPV, leading to unintended pregnancies, pregnancy complications, STIs, and other gynecological disorders and injuries related to IPV. An excellent opportunity exists for gynecologists and other women’s healthcare providers to assess, intervene, and provide resources for female patients experiencing IPV. IPV screening and counseling should be part of all women's preventative health and obstetric care. For pregnant patients, an assessment should take place at least once per trimester and again during the postpartum visit (ACOG, 2019).

Establishing Trauma-Informed Care for DV/SV Survivors

A systematic review of TIP concerning DV revealed that while many organizations have worked to identify survivors of abuse, there is less agreement on the best interventions for DV programs. The following six principles emerged within the study:

- establishing emotional safety

- restoring choice and control

- facilitating connection

- supporting coping

- responding to identity and context

- building strengths (Wilson et al., 2015)

Within these six principles, establishing emotional safety includes creating a physical environment that minimizes triggers. For example, the application of these principles might include an area for children to play or a comfortable waiting area with minimal stimulation. Staff should have a nonjudgmental approach with all interactions, including all questions asked. Programs should have well-developed policies related to TIC and communicate the policies clearly and effectively to all staff involved (Wilson et al., 2015).

Restoring choice and control allows the survivor to tell their "story" in their way within the time and space they choose. One study described this as helping "clients feel like it is their choice whether or not they share their story and telling their story is a choice, not a problem" (Wilson et al., 2015, p. 590). In contrast to a consistent "one-size-fits-all" methodology, allowing the client to make choices can help fuel their perception of being in control of their healing (Wilson et al., 2015).

Facilitating connection also supports healing by encouraging the survivor to connect with staff, other survivors, their families, and friends in the community. One of the most challenging aspects of this particular skill for staff is learning to interact with the survivor and form mutual relationships (Wilson et al., 2015).

Supporting coping validates the survivor's style of coping without judgment. There is not a specific way for the survivor to move through healing, and this step facilitates progress without dictating how it is done. The survivor should understand that their response to the trauma is appropriate and can help them to move through the healing process (Wilson et al., 2015).

Responding to identity and context may facilitate DV survivors accessing available services. A lack of cultural inclusivity often retraumatizes survivors and prevents them from feeling safe. Most importantly, this step allows the survivor to understand what happened to them. Questions that are asked allow the survivor to look within themselves and consider who they are and what happened during the abusive event(s; Wilson et al., 2015).

Potential areas for opportunity within TIC include improving how providers and nurses discuss the initial trauma, cultural competency, and survivor empowerment. While many organizations provide an optimal culture of care for the survivors of DV and SV, there were gaps identified in these areas within the systematic review (Wilson et al., 2015).

Similarly, the SAMHSA (2014) outlines their own six key principles of a trauma-informed approach:

- safety

- trustworthiness and transparency

- peer support

- collaboration and mutuality

- empowerment, voice, and choice

- cultural, historical, and gender issues (SAMHSA, 2014, para. 3)

Barriers to delivering TIC may be within an individual or an organization. One potential individual barrier is a lack of confidence in confronting survivors about their experiences. Healthcare professionals have reported fears of offending survivors when asking screening questions. Identification of this fear further supports the need for a culture where assessment for DV and SV is universal and not isolated to those perceived to be at-risk. Consistently, nurses cite a lack of training as a barrier to screening for DV and SV. Additional training, with opportunities for role-play or simulation, will allow for increased comfort and confidence when addressing these issues with patients. Institutional barriers may include a lack of time, perceived powerlessness to help, or marginalization by colleagues or the organization. Improved identification of abuse can be achieved through increased training, robust policies and procedures, and an expectation of universal screening of all patients (DeBoer et al., 2013).

If a healthcare provider determines that a patient is a victim or survivor of violence, they should acknowledge the trauma and assess the immediate safety of the patient and any children involved. A safety plan using local resources specific to their area is essential. The survivor should be given information on mental health services, crisis hotline numbers, rape relief centers, shelters, legal aid, and police contact information. It is incumbent upon each healthcare provider to have this information prepared in advance or to be able to access this information quickly if needed. The survivor should not be forced to accept assistance, and information should not be placed in their pocket or purse without their knowledge, as the perpetrator may find this information and escalate the violence. This also further diminishes the survivor’s sense of control and autonomy. It is optimal to offer a private phone call for the survivor to connect with a local DV agency, shelter, or the National Domestic Violence Hotline. Particularly if the survivor needs an interpreter, the NDV hotline is multilingual and can support survivors whose primary language is not English. Since an abusive partner may monitor the survivor's call logs, their personal phone should not be used (National Domestic Violence Hotline, 2019).

Mandatory Reporting

State and local reporting requirements vary by jurisdiction, and the nurse, physician, or healthcare provider should be familiar with their local and state expectations. Any known or suspected violence against vulnerable populations is required to be reported in the United States, although specific regulations will vary by state. Vulnerable individuals include children, older adults, and the mentally disabled. Failure to report suspected abuse can lead to hefty fines or possible incarceration for the nurse or other healthcare provider (Peate, 2017).

Reporting suspected abuse of a child is mandatory in all states. Child abuse and neglect must be reported to the relevant local and/or state department if there is reasonable cause to believe a child may be suffering physical or emotional abuse by specified mandated reporters in 47 states and the District of Columbia; the remaining three states, Indiana, New Jersey, and Wyoming, require all persons to report regardless of profession. In 15 states and Puerto Rico, all residents are also required to report suspected child abuse. Reporting should include harm or substantial risk of harm to a child's health or welfare, sexual abuse, neglect, malnutrition, or physical dependence on a drug at birth (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2019). Reporting may also be required for incidents involving elders or persons with disabilities in many states. However, adult reporting of DV is controversial. Some states do not mandate reporting of DV in adults as it could escalate the violence. Additional acts of violence related to physical injuries may also require reporting (ACOG, 2019).

Most states require that injuries caused in violation of criminal law by either intentional or non-accidental means or involving the use of a weapon are reported to the proper authorities. To ensure compliance with state and federal laws related to reporting, local law enforcement or domestic violence agencies can help guide the nurse or healthcare provider to specific jurisdictions (Futures without Violence, 2019).

Many states have increased penalties for DV that is committed in the presence of a child. Nine states consider an act of violence in the presence of a child to be "aggravating circumstances" during their sentencing guidelines (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016).

Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is considered a violent crime and should be addressed when discussing DV and SV. Human trafficking is modern slavery and may take the form of labor trafficking or sex trafficking. It is characterized by exploiting an individual with force, fraud, or coercion to either work or perform sexual acts. Risk factors for human trafficking targets include living in unsafe situations, poverty, members of vulnerable populations, or those in an environment of abuse at home. Sex trafficking affects the survivor's health, including increased risk for HIV/AIDS, STIs, pelvic pain, rectal trauma, or urinary difficulties. Potential long-term consequences for survivors of sex trafficking also include pregnancy secondary to rape or prostitution, infertility related to chronic, untreated STIs or unsafe abortions, infections or mutilations caused by sex trafficker's "doctors," chronic back pain, malnourishment, dental problems, diabetes, cancer, or infectious diseases such as tuberculosis. Physical signs of abuse, such as bruises, bites, and scars, may be present. The injuries may be in areas that are not readily seen, such as the lower back. Substance abuse problems are often seen in sex workers as they are either forced to take them by their perpetrators or use them voluntarily to cope with the situation. Mental health issues such as depression, panic attacks, shock, denial, or shame are common among survivors of human trafficking (CDC, 2019f).

There has been an increased awareness of human trafficking in recent years. The Trafficking Victims Protection Act was originally developed in 2000 by President Bill Clinton to train and outline services needed for survivors of human trafficking; it was reauthorized in 2017 to further expand resources and further address the needs of survivors. The emphasis of prevention efforts should be on encouraging healthy behaviors in relationships, fostering safe homes and neighborhoods, identifying vulnerabilities during healthcare visits, reducing the demands for commercial sex, and ending business profits from trafficking-related transactions (CDC, 2019f).

PTSD and Domestic Violence

The long-term effects of DV and SV may include PTSD. The American Psychiatric Association (2017) defines PTSD as "a psychiatric disorder that can occur in people who have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event such as a natural disaster, serious accident, terrorist act, war/combat, rape or other violent assault." Those experiencing PTSD have distressing thoughts and feelings toward their experience that last long after the event is over. The individual could experience flashbacks, nightmares, sadness, fear or anxiety, anger, and may exhibit poor interpersonal relationships, including attachment issues. A person with PTSD can have strong adverse reactions to loud noises or an accidental touch. Symptoms of PTSD have four categories: intrusive thoughts, avoiding reminders, negative thoughts and feelings, or arousal and reactive symptoms. To be diagnosed with PTSD, some form of these symptoms should be exhibited for more than a month and may persist for years. PTSD may occur in combination with other mental health conditions such as depression or substance abuse (American Psychiatric Association, 2017).

Anyone that has been impacted by DV or SV can develop PTSD, and in most cases, the condition is complex. The factors related to PTSD in DV and SV survivors can include:

- feelings of guilt related to the violence

- the age of the survivor

- the duration of the trauma or abuse

- the survivor’s personal perception of the trauma

- a lack of social support

- an inability to stop the abuse or violence (Lacasa et al., 2018).

PTSD can occur from not only real threats but also perceived ones, and early recognition can avoid many of the long-term implications of PTSD. Children who are survivors of DV or SV do not respond well to the standard treatment of reliving their experience during therapy. This group responds best to emotional regulation and group therapy that allows them to discuss their feelings. Adults with a history of abuse as children may also benefit from this treatment. A multi-faceted approach to caring for survivors of DV and SV with PTSD is vital to promote safety, self-care, and protection from further violence (Lacasa et al., 2018).

National Resources:

- National Domestic Violence Hotline- (800) 799-7233

- National Sexual Assault Hotline- (800) 656-4673

References

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2019). Intimate partner violence. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co518.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20190905T2148322459

American Psychiatric Association (2017). PTSD. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd

American Psychological Association. (2016). Violence & socioeconomic status. https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/violence

American Psychological Association (2019). Trauma. https://www.apa.org/topics/trauma/

Bellis, M., Hardcastle, K., Ford, K., Hughes, K., Asthon, K., Quigg, Z., & Butler, N. (2017). Does continuous trusted adult support in childhood impart life-course resilience against adverse childhood experiences: A retrospective study on adult health-harming behaviors and mental well-being. Psychiatry, 17(110). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1260-z

Black, B., Hawley, A., Hoefer, R., & Barnett, T. (2017). Factors related to teenage dating violence prevention programming in schools. National Association of Social Workers, 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdx007

Breiding, M.J. & Armour, B.S. (2015). The association between disability and intimate partner violence in the United States. Annals of Epidemiology, 25(6), 455-457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.017

Brem, M. J., Florimbio, A. R., Elmquist, J., Shorey, R. C., & Stuart, G. L. (2018). Antisocial traits, distress tolerance, and alcohol problems as predictors of intimate partner violence in men arrested for domestic violence. Psychology of Violence, 8(1), 132–139.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2014). Providing quality family planning services: Recommendations of CDC and the US office of population affairs. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63(4), 1-60.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/NISVS-infographic-2016.pdf

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019a). Elder abuse. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/elderabuse/index.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019b). Preventing child abuse and neglect. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/fastfact.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019c). Preventing sexual violence. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/fastfact.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019d). Preventing youth violence. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/youthviolence/fastfact.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019e). Public health approach to violence. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/publichealthissue/publichealthapproach.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019f). Sex trafficking. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/trafficking.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). Preventing intimate partner violence. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). Preventing teen dating violence. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/teendatingviolence/fastfact.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020c). Risk and protective factors. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/riskprotectivefactors.html

The Center for Healthcare Strategies (n.d.) What is trauma informed care? Retrieved December 9, 2020, from https://www.traumainformedcare.chcs.org/what-is-trauma-informed-care/

Child Welfare Information Gateway (2019). Mandatory reporters of child abuse and neglect. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/manda.pdf

Cohodes, E., Hagan, M., Narayan, A., & Lieberman, A. (2016). Matched trauma: The role of parent's and children's shared history of childhood domestic violence exposure in parents' report of children's trauma-related symptomatology. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 17(1), 81-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2015.1058878

Criminal Justice Research (n.d.). The rule of thumb and domestic violence. Retrieved September 10, 2019, from http://criminal-justice.iresearchnet.com/crime/domestic-violence/rule-of-thumb/

Dargis, M., & Koenigs, M. (2017). Witnessing domestic violence during childhood is associated with psychopathic traits in adult male criminal offenders. Law and Human Behavior, 41(2), 173–179.

DeBoer, M. I., Kothari, R., Kothari, C., Koestner, A. L., & Rhos Jr, T. (2013). What are barriers to nurses screening for intimate partner violence? Journal of Trauma Nursing, 20(3), 155–160.

The Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs (2017). The Duluth model: Power and control wheel. https://www.theduluthmodel.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/03/PowerandControl.pdf

Elkins, J., Crawford, K., & Briggs, H. (2017). Male survivors of sexual abuse: Becoming gender-sensitive and trauma-informed. Advances in Social Work, (1), 116. https://doi.org/10.18060/21301

Family & Youth Services Bureau. (2016). Domestic violence and homelessness: Statistics. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/fysb/resource/dv-homelessness-stats-2016

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., Shattuck, A., & Hamby, S. L. (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the National Survey of Children's Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(8), 746–754. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676

Futures without Violence (2019). Mandatory reporting of domestic violence by healthcare providers. https://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/mandatory-reporting-of-domestic-violence-by-healthcare-providers/

Hardy, A., & Rice, K. (2016). Violence and residual associations among Native Americans living on tribal lands. The Professional Counselor, 6(4), 328-343.

HelpGuide (2019). Domestic violence and abuse. https://www.helpguide.org/articles/abuse/domestic-violence-and-abuse.htm

Indu, P. (2018). Mental health implications of elder abuse and domestic violence. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 40(6), 507–508. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_438_18

Lacasa, F., Álvarez, M., Navarro, M.Á., Richart, M.T., San, L., & Ortiz, E.M. (2018). Emotion regulation and interpersonal group therapy for children and adolescents witnessing domestic violence: A preliminary uncontrolled trial. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11(3), 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-016-0126-8

National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (n.d.). Domestic violence. Retrieved September 11, 2019, from https://www.speakcdn.com/assets/2497/domestic_violence2.pdf

National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (2016). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and HIV-affected intimate partner violence in 2015. https://avp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2015_ncavp_lgbtqipvreport.pdf

National Conference of State Legislatures (2019). Domestic violence/domestic abuse definitions and relationships. http://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/domestic-violence-domestic-abuse-definitions-and-relationships.aspx

National Domestic Violence Hotline (2019). Immigrants in the US have the right to live life free of abuse. https://www.thehotline.org/is-this-abuse/abuse-and-immigrants-2/.

National Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence (2017). Prevent, assess, and respond: A domestic violence tool-kit for health centers & domestic violence programs. http://ipvhealthpartners.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/IPV-Health-Partners-Toolkit-8.18.pdf.

National Resource Center for Domestic Violence. (n.d.) Domestic violence victims/survivors: Defining the problem and the population. Retrieved September 18, 2019, from https://www.nrcdv.org/rhydvtoolkit/each-field/violence-victims/define.html

Peate, I. (2017). Domestic violence against men. British Journal of Nursing, 26(6), 309. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2017.26.6.309

Petrosky, E., Blair, J., Betz, C., Fowler, K., Jack, S., & Lyons, B. (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in homicides of adult women and the role of intimate partner violence. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(28), 741-746. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6628a1

Potera, C. (2014). The VAWA makes American Indian women safer. American Journal of Nursing Online, 114(5).

Rakovec-Felser, Z. (2014). Domestic violence and abuse in intimate relationship from public health perspective. Health Psychology Research, 2(3), 1821. https://doi.org/10.4081/hpr.2014.1821

Ronzon-Tirado, R.C., Munoz-Rivas, M.J., Zamarron-Cassinello, M.D., & Rodrigue, N.R., (2019). Cultural adaptation of the modified version of the conflicts tactics scale (M-CTS) in Mexican adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(619) 1-9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00619

Rural Health Information Hub. (2018). Violence and abuse in rural America. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/violence-and-abuse

Stockman, J. K., Hayashi, H., & Campbell, J. C. (2015). Intimate partner violence and its health impact on disproportionately affected populations, including minorities and impoverished groups. Journal of Women's Health, 24(1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.4879

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (n.d.). Intimate partner violence. Retrieved September 15, 2019, from https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/intimate-partner-violence#Providers

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. https://youth.gov/feature-article/samhsas-concept-trauma-and-guidance-trauma-informed-approach

Tasbiha, N. S. (2017). Spousal abuse in Bangladesh: An overview. ASA University Review, 11(2), 57–66.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016). Child witnesses to domestic violence. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/witnessdv.pdf

U.S. Department of Justice. (2018). Domestic violence.

https://www.justice.gov/ovw/domestic-violence

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2019). Screening for intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and abuse of vulnerable adults: Recommendation statement. American Family Physician, 99(10). https://www.aafp.org/afp/2019/0515/od1.html

Usta, J., & Taleb, R. (2014). Addressing domestic violence in primary care: What the physician needs to know. The Libyan Journal of Medicine, 9. https://doi.org/10.3402/ljm.v9.23527

Wilson, J. M., Fauci, J. E., & Goodman, L. A. (2015). Bringing trauma-informed practice to domestic violence programs: A qualitative analysis of current approaches. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(6), 586-599. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ort0000098.

Yakubovich, A. R., Stöckl, H., Murray, J., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Steinert, J. I., Glavin, C. E., & Humphreys, D. K. (2018). Risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence against women: Systematic review and meta-analyses of prospective-longitudinal studies. American Journal of Public Health, 108(7), e1–e11. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304428