About this course:

The purpose of this course is to familiarize the learner with the components and evidence-based methodology of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) for older adult patients.

Course preview

At the conclusion of this course, the advanced practice nurse (APRN) will be prepared to:

- explain the purpose of performing a comprehensive geriatric assessment for certain older adult patients

- discuss the process and essential components of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA)

- outline the members of the care team performing a comprehensive geriatric assessment and expected outcomes

When caring for older adults (65 years and older), nurses must account for various unique considerations. The healthcare team must be sufficiently prepared to care for these patients, as the population of Americans over the age of 65 is expected to more than double between 2000 and 2030, increasing from 34.8 million to more than 70.3 million. Best-practice and evidence-based geriatric protocols should be developed and utilized in hospitals, rehabilitation centers, long-term care (LTC) facilities, home-care agencies, and community clinics; these protocols should be introduced in nursing education programs to enhance familiarity. APRNs must function in tandem with the rest of the interdisciplinary team, as the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) highlighted collaboration as vital to the care of the aging in their Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce report in 2008. The primary goals of geriatric care should be to promote well-being and optimize QOL through continued maintenance of function, dignity, and self-determination (Brown-O'Hara, 2013; Ward & Reuben, 2020).

A Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

Older adults represent the most complex patients within health care. Overlooking or misidentifying an underlying cause for a patient's chief complaint frequently occurs, leading to extensive consumption of healthcare resources through urgent care or emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations. These missed diagnoses cause increased morbidity, mortality, and ultimately disability. These miscues also lead to frustration and distrust among patients, not to mention the frustration these situations can prompt for caregivers and healthcare providers (HCPs). A comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) may help identify conditions and syndromes earlier and more accurately. CGAs should be multidisciplinary in order to identify not just medical but also functional and psychosocial limitations. A full assessment should also obtain information regarding the patient's current functional and instrumental activities of daily living (ADLs and iADLs); gait, balance, and fall risks; visual and auditory acuity; mood, memory, executive functioning, and problem-solving; and risk for or presence of skin breakdown. A series of assessment tools may be utilized for this process. For example, the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) is a validated measure of cognition. The Fulmer SPICES tool assesses older adults for sleep disturbances, problems with eating or feeding, incontinence, confusion, evidence of falls, and skin breakdown. The Advancing Care Excellence for Seniors (ACE.S) framework was created by the Community College of Philadelphia in partnership with the National League for Nursing (NLN) as an educational guide to instruct nursing students on how to assess an older patient's function, identify their expectations, and work through shared decision-making to coordinate care and manage any identified deficits or conditions to improve QOL and reduce caregiver stress. The established care plan should be well-coordinated across disciplines, culturally inclusive and sensitive, and tailored to the individual's unique wishes, resources, and strengths. Assessing a patient's relative risk will help identify early prevention strategies to incorporate and avoid complications. For example, the ACE.S framework highlights the heightened risk associated with transitions, of which many occur later in life. These transitions happen when an individual is adjusting to life with adult children, learning to function after a spouse’s death, moving to a different environment, or moving between care settings. The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing (HIGN) developed a series of assessment tools entitled Try This. These 2-page guides provide information and an assessment for particular conditions that can be completed by the HCP in under 20 minutes. These tools can be accessed free of charge on Hartford’s website, hign.org. The SPICES tool mentioned above is the first item in the Try This series (Brown-O'Hara, 2013; HIGN, n.d.; Tagliareni et al., 2012; Ward & Reuben, 2020).

Patients who should be considered for referral to a CGA program include those who are over 65 years with one or more chronic or complicated health conditions. CGA programs are most beneficial for moderately ill patients, but not those at either end of the wellness spectrum who are either very healthy or gravely ill. For this reason, CGA programs are most appropriate for patients with medical comorbidities (e.g., heart failure, cancer), psychosocial disorders (e.g., depression, isolation, dementia), certain high-risk conditions (e.g., falls, functional disabilities), and a history of or a risk for a high rate of healthcare utilization, as well as those experiencing a change in their living situation (e.g., beginning services with in-home caregivers, moving from their home to an assisted living facility). Most programs rely on a core team consisting of a nurse, a clinician, and a licensed social worker (LSW) to complete the assessment. Ancillary professionals are used on a case-by-case basis, such as physical therapists (PTs), occupational therapists (OTs), speech and language pathologists (SLPs), dietitians, pharmacists, psychiatrists, psychologists, dentists, audiologists, podiatrists, and opticians. Assessment programs may be limited by local access and reimbursement for certain services, and assessments are often broken into separate components; team communication is completed virtually through the electronic health/medical record (EHR/EMR). A CGA typically consists of 6 steps: (a) data gathering, (b) discussion among the team, (c) development of a treatment plan, (d) implementation of the treatment plan, (e) monitoring the patient's response to the plan, and (f) revision of the treatment plan if needed. Both the second and third steps should involve participation by and input from the patient and their caregivers if possible. Many programs have shifted the focus away from tertiary prevention to incorporate primary and secondary prevention strategies. Written (or electronic) questionnaires can save valuable time by gathering a large amount of information prior to the assessment, allowing the team to focus on areas of concern. The preliminary questionnaire will typically review the patient’s history (i.e., past medical history, current medications, social history, review of systems, surgical history), as well as information regarding the current level of function, assistance required for ADLs and iADLs, fall history, urinary or fecal incontinence, pain, mood symptoms, and vision or hearing difficulties. It should also inquire about the patient's social support network and the existence of any advance directives such as a durable power of attorney or proxy decision-maker for health care. The core components of most CGAs include the following:

- functional capacity (the ability to drive and perform other basic, instrumental, and advanced ADLs)

- fall risk

- cognition

- mood

- social support

- financial concerns

- goals of care

- advance care preferences

- polypharmacy (Ward & Reuben, 2020)

Optionally, some CGAs may also include an assessment of the patient's:

- nutrition or recent weight changes

- urinary incontinence

- sexual function

- vision/hearing

- dentition

- living situation

- spirituality (Ward & Reuben, 2020)

Functional Capac

...purchase below to continue the course

Functional capacity refers to a patient's ability to perform basic, instrumental, and advanced activities of daily living. This can include toileting, grooming, eating, cooking, driving, and managing finances. If a patient loses the ability to perform these tasks, they are often described as experiencing a functional decline (Ward & Reuben, 2020). Physical frailty in older adults is typically defined as weight loss, malnutrition, slow gait, fatigue, weakness, and inactivity. Failure to thrive (FTT) in older patients is a syndrome of global decline consisting of weight loss, decreased appetite, poor nutrition, and inactivity that is often accompanied by dehydration, symptoms of depression, impaired immunity, and reduced cholesterol. As opposed to the FTT syndrome that affects pediatric patients, who cannot achieve an expected functional level, older adults with the same complex of symptoms are unable to maintain their previously acquired functional status. These terms may be used interchangeably or describe distinct points along a continuum between the virility and independence associated with middle age and the complete dependence and death at the end of life. For example, a patient may decline in their ability to function independently, beginning with a classification of robust and declining to pre-frail, then frail, and finally qualifying as FTT near the end of their life. Other experts consider physical frailty to be a component of FTT, along with physical disability and neuropsychiatric impairment, although these latter components are not required to diagnose FTT. FTT and frailty are often related to adverse effects of medication(s) and medical comorbidities and are compounded by psychosocial factors. An accurate assessment of the patient’s prior level of functioning or baseline is crucial to establishing a significant change or downward trend (Agarwal, 2020).

Functional capacity, or frailty, should be assessed in older patients to determine their prognosis regarding functional decline and death in an upcoming period and help differentiate patients who may not derive significant benefit from treating asymptomatic chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension; Ward & Reuben, 2020). As a component of the CGA, functional capacity should be assessed using a validated tool such as the Vulnerable Elders Scale-13 (VES-13), a screening tool with 13 items related to age, self-rated health, and the ability to perform certain functional and physical activities. It is designed to predict the potential for functional decline or death within the next 5 years for community-dwelling patients over 65. It can be self-administered during an office visit or by nonmedical personnel via telephone in under 5 minutes. Scores range from 1 to 10, with higher scores indicating a worse prognosis. Research suggests that patients whose VES-13 score is 3 or higher have 4.2 times the odds of functional decline or death within the next 2 years compared to patients with a score of 2 or below (Min et al., 2009; Ward & Reuben, 2020).

The Karnofsky Performance Status Scale was developed in the early 1990s to compare the effectiveness of different therapies and establish a prognosis for patients. The scale assigns a score of 0-100 based on the patient's description of their functional abilities (Christensen, 2018). Similarly, the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) is commonly used to assess functional capacity in clinical practice due to its brevity. This Canadian tool purports to "summarize information based on a clinical encounter" and "roughly quantify an individual's overall health status" by assigning a score (Dalhousie University, 2020, P. 1). The scores ranged from 1 ("very fit, indicating a patient who is robust, active, energetic, motivated and fit") to 7 ("severely frail, completely dependent on others for ADLs or terminally ill") in the original scale (Dalhousie University, 2020, p. 1; Rockwood et al., 2005). The CFS was expanded in 2007, adding scores of 8 and 9 to characterize more severe cases of frailty and differentiate between severely frail, very severely frail, and terminally ill patients. Finally, in 2020 version 2.0 was released with minor edits to the categorical descriptions. The authors note that using the scale requires clinical judgment after observing a patient's mobility, balance, use of a walking aid, and reports of their ability to dress, feed themselves, cook, shop, and manage their finances. The user must simply ask the patient (or an accompanying caregiver) how they have been moving, functioning, thinking, and feeling about their health over the previous 2 weeks. The authors also recommend reviewing the patient's current medications (to ascertain pre-existing medical conditions) and a question about the patient's activity level. How the patient is moving, functioning, thinking, and engaging in activity helps differentiate between the first three categories. In categories 4-7, cognition plays a more prominent role, and his or her activity/exercise habits are less conspicuous. Patients in categories 8 and 9 are considered to be near the end of life, with 9 representing those with under 6 months of estimated life left. If a patient fits equally well in two categories, the authors recommend assigning the higher (more dependent) score. Scores should be based on knowledge of the patient's baseline health state. The CFS has not been validated for use in younger patients (Dalhousie University, 2020; Rockwood & Theou, 2020).

The Katz Index of Independence in ADL scale assesses a patient's essential life skills and is included in the second issue of the Try This series by the HIGN. The Lawton IADL scale is designed for use in community-dwelling populations and is included in the 23rd issue of the Try This series by the HIGN. A simple observation of the patient dressing or undressing may give valuable information regarding their functional status, range of motion, apraxia (difficulty executing skilled movements or activities), and balance (Agarwal, 2020). Some health-related QOL instruments also include ADL components, such as the Medical Outcomes Study Short-form, the Short Form Health Survey (SF-12), and the PROMIS instruments. Aside from ADLs, gait speed can accurately predict functional decline and early mortality. Gait speed can be assessed by timing the patient while they walk 6 meters or 20 feet. Research indicates persistent untreated hypertension only increases mortality in patients over 65 if their gate speed is at least 0.8 m/second (Ward & Reuben, 2020). The timed Get Up and Go test is another option for assessing gait speed and is discussed in greater detail in the forthcoming section on Falls Risk (Agarwal, 2020).

Frailty

Frailty prevalence estimates vary between 4% and 16% of community-dwelling adults over 65. Risk factors for frailty in the US patient population include older age, lower educational level, smoking, hormone replacement therapy, African American or Hispanic American ethnicity, unmarried status, depression or the administration of antidepressants, and intellectual disability (Walston, 2020). Female patients and those with lower incomes, more comorbidities, and poorer overall health also have an increased risk (Voelker, 2018). Frailty has been shown to increase mortality risk and the risk of hip fracture, disability, and hospitalization. The pathophysiology of frailty may be related to the dysregulation of the patient's stress response system, which typically involves endocrine, immune, and metabolic dysfunction. Some age-related changes that are associated with frailty include decreased hormone production (growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, reproductive hormones, and vitamin D), increased cortisol levels, increased inflammatory markers (interleukin 6 and c-reactive protein [CRP]), altered glucose metabolism, dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, and changes in the renin-angiotensin system and cellular mitochondria. Frailty may be diagnosed or assessed for using either of two methods: a physical or phenotypic approach is designed to capture signs and symptoms indicative of vulnerability to poor outcomes, while a deficit accumulation or index method identifies cumulative comorbidities and illnesses. Although a patient's age, comorbidities, and disability are typically associated with frailty, these components should not be used to diagnose the syndrome (Walston, 2020). Dozens of frailty measurement tools have been developed for use. The Cardiovascular Health Study provided some diagnostic criteria for frailty, entitled the Fried Frailty Tool or Frailty Phenotype. This tool is validated to assess physical frailty, although it is somewhat difficult to utilize in a clinical setting. This phenotype is identified in patients meeting at least three of the following five characteristics:

- weight loss (at least 5% of body weight within a year)

- exhaustion (based on the patient's report regarding effort required for activity)

- weakness (may be based on decreased grip strength)

- slow gait speed (more than 6 seconds to ambulate 15 feet)

- reduced physical activity (under 270 kcal expended/week for females, 383 for males; Agarwal, 2020; Walston, 2020)

A deficit accumulation or index approach to diagnosing frailty involves the patient's accounting of their current medical and functional status or history to identify their illnesses, functional and cognitive decline, and social factors. These elements are combined to establish the patient's frailty score. The most common rationale for utilizing this method over the physical frailty approach is that the patient's cognitive decline is considered a factor. This is vital, as frailty is associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline, and cognitive decline increases a patient's risk of adverse outcomes (Walston, 2020).

Several rapid screening tools for frailty are often used to identify older adult patients at increased risk and qualification for a formal CGA. The CFS is an example, as previously described. The FRAIL scale can be completed quickly during a patient's history. It includes asking the patient about:

- fatigue (have you felt fatigued most or all the time in the last month?),

- resistance (do you have difficulty climbing a flight of stairs?),

- ambulation (do you have difficulty walking a block?),

- illnesses (do you have any chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes mellitus [DM], cancer, hypertension, chronic lung disease, heart disease or heart failure, angina, asthma, kidney disease, or a history of stroke or heart attack?), and

- loss of weight (more than 5% of your body weight in the last year without trying?).

Each question is answered with yes or no, with 1 point assigned for each affirmative answer. A score of 0 represents a robust patient, 3-5 represents a frail patient, and some categorize a score of 1 or 2 as pre-frail. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) frailty tool assesses for unintentional weight loss (5% of body weight in the last year), the ability to stand from a seated position in a chair five times without using the arms, and whether the patient feels "full of energy." A positive screening indicating the need for further evaluation is defined as meeting two of the three components. The Edmonson scale uses a series of 14 questions to assess a patient's general health, function, cognition, social support, and nutrition (Walston, 2020).

If frailty is suspected, the patient history should include a detailed account of their energy level, including their reports of fatigue. Caregiver observations regarding their ability to function should also be included, with specific accounts of their ability to maintain activity such as climbing a flight of stairs or walking a block without needing to stop and rest. The patient's exam should include asking them to stand up five times from a seated position without using the chair's armrests for support. The provider should note how the patient walks down the hall and within the exam room to assess ambulation (Walston, 2020).

Any physical assessment of an older adult should include height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and notation of any recent changes (in the last year) and whether these changes were intentional. Malnutrition in an older adult patient may initiate a cycle of frailty, leading to a decrease in lean muscle mass, which reduces strength, aerobic capacity, gait speed, and activity level, resulting in functional decline and progressive frailty (Agarwal, 2020). Although weight loss is central to the frailty phenotype, patients with poor nutrition who satisfy at least three of the remaining four characteristics may still be diagnosed as frail. This is especially important for frail older adults with obesity who may not exhibit the weight loss expected. As mentioned earlier, the assessment of recent weight changes is a common (although not required) component of a CGA. Causes of weight loss should be explored, including inadequate intake (e.g., adverse medication effects, socioeconomic factors, poor oral health, xerostomia [dry mouth]) or increased energy expenditure (e.g., increased activity, medical conditions). The mnemonic MEALS ON WHEELS summarizes some of the common causes for malnutrition and unintentional weight loss in adults:

- medications (e.g., antiepileptic drugs [AEDs], digoxin [Lanoxin], anticholinergics, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, antibiotics, chemotherapeutic agents)

- emotional problems (e.g., mood disorders such as depression or anxiety)

- anorexia (loss of appetite, anorexia nervosa or tardive)

- late-life paranoia or alcoholism

- swallowing disorders (e.g., odynophagia [painful swallowing], dysphagia [difficulty swallowing])

- oral factors (e.g., dental carries/abscess, ill-fitting dentures, xerostomia)

- no money (e.g., economic hardship, food desserts, lack of transportation to obtain food)

- wandering (i.e., in dementia patients)

- hyperthyroidism or hyperparathyroidism

- entry problems/malabsorption

- eating problems (e.g., upper extremity or jaw weakness due to stroke, tremor)

- low-salt or low-cholesterol diet

- shopping and food preparation problems (e.g., food deserts, lack of transportation to obtain food; Agarwal, 2020, Tables 1 & 2)

Multiple medical conditions can also contribute to weight loss, such as malignancy (the most common), gastrointestinal conditions (e.g., peptic ulcer disease, chronic pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease), cardiac conditions (e.g., heart failure, coronary artery disease), pulmonary conditions (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], interstitial lung disease), infectious conditions (e.g., tuberculosis [TB], bacterial endocarditis), neurologic conditions (e.g., stroke, dementia, Parkinson's disease), endocrine disorders (e.g., DM, thyroid dysfunction), renal conditions (e.g., uremia, nephrotic syndrome), psychiatric conditions (e.g., depression, alcohol use disorder), or rheumatic conditions (e.g., polymyalgia rheumatica). Malnutrition and weight loss can indicate a deficiency in thiamine, vitamin B12, vitamin C, or zinc (Agarwal, 2020, Table 3). In addition, differential diagnoses to consider when evaluating a patient at risk for frailty should include other conditions that may lead to unintentional weight loss, functional decline, fatigue, and weakness, such as vasculitis, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, chronic kidney disease, anemia, and vascular dementia (Walston, 2020).

A comprehensive history of weight loss should include access to food; the number, size, and content of daily meals; assistance required for grocery shopping, meal preparation, or eating; difficulty with chewing; and any associated symptoms of anorexia, early satiety, or dysphagia. A validated tool can help identify anorexia, malnutrition, or risk for malnutrition, such as the Simplified Nutritional Assessment Questionnaires (SNAQ) or the Mini-Nutritional Assessment. The physical examination should include an assessment of the oral cavity. Additionally, a consultation with an SLP or dietitian can further ascertain the underlying etiology of unintentional weight loss and inform an appropriate treatment plan to address the identified issues (Agarwal, 2020).

Failure to Thrive (FTT)

A comprehensive history should be used to identify potential medical or psychiatric comorbidities or prescription medications contributing to FTT. The patient should be asked about any alcohol or illicit drug use. A review of systems should be completed to elucidate when and how symptoms initially emerged and changed with time. Systemic immune symptoms (e.g., fever, chills, pain, sweating) may indicate a chronic infectious process, such as TB, bronchiectasis, or endocarditis. A patient's decline in vision or hearing may contribute to inactivity and functional decline, so essential vision and hearing screens should be completed to rule out either of these conditions as a contributing factor. A brief physical exam should be used to identify any orthopedic or rheumatologic concerns leading to inactivity, such as arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, or podiatric conditions. Feeding difficulties and other causes of malnutrition, as outlined above, should be reviewed and eliminated or addressed as appropriate (Agarwal, 2020). Laboratory testing for patients with FTT should include the following:

- complete blood count (CBC) with differential

- basic metabolic profile (BMP)

- liver function studies, including albumin

- urinalysis

- serum calcium and phosphate

- thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- vitamin B12 and folate level

- total cholesterol

- 25-hydroxyvitamin D (Agarwal, 2020; Walston, 2020)

Additional laboratory studies or diagnostic imaging may also be indicated, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), CRP, blood cultures, and a chest radiograph to rule out infection or other imaging studies if malignancy is suspected (Agarwal, 2020).

As previously mentioned, the components of FTT typically include neuropsychiatric impairment and are often accompanied by symptoms of depression. This impairment facilitates the worsening of malnutrition, disability, and frailty. Delirium, dementia, and depression are the most likely etiologies for cognitive decline in older adults, which can also be due to underlying medical conditions or adverse effects of medication (e.g., anticholinergics). Delirium can be defined as an acute deterioration in cognitive function and attention. Risk factors for delirium include dementia, sensory impairment, severe illness, depression, hypovolemia (volume depletion), and medical comorbidities. Delirium makes the CGA process more challenging, especially when assessing mood (e.g., for depression and other mood disorders) and cognition (e.g., for dementia). During mental status or cognitive screening, insufficient attention from the patient should prompt the healthcare team to consider possible delirium. Mood disorders, such as depression, may cause disability, malnutrition, weight loss, frailty, and FTT. Depression increases mortality risk in older adults, with an incidence rate of 5% (in community-dwelling older adults) to 25% (in the LTC population; Agarwal, 2020; The American Geriatric Society [AGS] Beers Criteria [BC] Update Expert Panel, 2019). The screening process for dementia is discussed in greater detail in the forthcoming Cognition section of this activity, while depression screening is discussed in the upcoming Mood section.

Fall Risk

Patients with inadequate balance/gait disturbance or a history of falls have an increased risk for future falls, thereby risking their independence. Each year, up to one-third of community-dwelling patients over age 65 (and up to one-half of those over age 80) suffer a fall (Ward & Reuben, 2020). The etiology of a fall is typically multifactorial, consisting of an acute threat to the patient's standard homeostatic mechanisms (e.g., acute illness, a new medication, environmental stress) in combination with an age-related decline in balance, gait stability, and cardiovascular function. The first step in assessing risk is a simple history regarding falls in the last year. Additional risk factors include lower extremity weakness, age, female sex, cognitive impairment, impaired balance, use of psychotropic medication(s), arthritis, stroke history, orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, and anemia. Of these, gait or balance disturbance was the most consistent risk factor across numerous studies, followed by medications. Falls associated with syncope or that occur in patients with a prior history of a fall with injury or who present with decreased executive functioning are at increased risk of significant harm (Kiel, 2020). Cognitive impairment and depression affect the brain's executive functioning, including high-level balance and gait coordination (Frith et al., 2019). Polypharmacy increases the risk of falls and should be carefully considered before prescribing a new medication or during the assessment to prevent or arrange a workup after a patient fall (Saljoughian, 2019). Medicines that are consistently correlated with patient falls include central nervous system (CNS) active drugs such as neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, and antidepressants, as well as vasodilators for hypertension or heart rate (HR) control (Kiel, 2020). The AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults—generally known as The Beers Criteria—was last updated in 2019. This list includes the following medications that should be avoided for older patients at risk of falls: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs, which were newly added since the 2015 list was released), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), anticonvulsants (AKA antiepileptic drugs, or AEDs), antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, nonbenzodiazepine receptor agonist hypnotics (Z drugs, such as zolpidem [Ambien], zaleplon [Sonata], and eszopiclone [Lunesta]), and opioids, specifically mu-opioid receptor agonists (AGS Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel, 2019; Fixen, 2019). Alcohol use increases the risk of falls among patients over age 65, as does going barefoot or wearing shoes with an elevated heel; the use of footwear with a thin, hard sole or minimal heel height appears to reduce the risk of falls, although the research on footwear is minimal and can be conflicting. Patients should be instructed to remove any obvious home hazards such as loose throw rugs to reduce the risk of falls, although the research regarding the effectiveness of this type of intervention is lacking (Kiel, 2020).

The recommendations regarding assessments for fall risk are based on those endorsed by the AGS, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS), and the British Geriatrics Society. Patients over 65 should be asked at least once a year about falls or difficulties with balance or gait. Those who report a single fall should undergo a gait and balance evaluation during the physical exam using a validated test, such as the Tinetti Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment (POMA) tool or the Get Up and Go test. The POMA tool takes 10-15 minutes to administer and produces a score ranging from 0-28 based on nine balance tests and seven gait tests. A score of 25 or higher indicates a low fall risk, while a score under 19 indicates a high fall risk. The Get Up and Go test added a timed component and was then referred to as the timed Get Up and Go test or TUG. The scale ranges from 1 (regular, well-coordinated movements and no walking aid) to 5 (severely abnormal as evidenced by the need for standby physical support). The patient is seated in an armchair of standard height to begin the test. They are instructed to stand (without using the chair arms if possible), walk forward 10 feet (3 meters), turn around, return to the chair, turn around again, and be seated. The examiner is instructed to note the patient's sitting balance, ability to transfer and turn or pivot, and pace and stability of walking. The timed test should begin upon standing, end with re-seating, and be compared to results from an age-adjusted cohort, as listed in Table 1 (Kiel, 2020).

A patient with a TUG test time of greater than 20 seconds may not be physically safe to transfer or venture out of the house independently (Agarwal, 2020). Additional options available to assess musculoskeletal function quickly in an older patient include the functional reach test, the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), or the Berg Balance Test. The functional reach test involves a patient standing with both feet planted and their shoulders perpendicular to a mounted yardstick at the level of the acromion. The patient is instructed to reach with a closed fist as far forward as possible without taking a step or losing their balance, measuring their total reach with the yardstick. Reaches below 6 inches indicate an increased risk of falls. The SPPB captures a wide range of functional abilities, asking the patient to perform tandem, semi-tandem, and side-by-side stands; a 4-meter timed walking test; and raises from a chair five times. Components are predictive of falls, and scores below 9 indicate disability in ADLs and mobility within 1 to 6 years. The Berg Balance test is easy to administer and common in rehabilitation, inpatient, and outpatient settings and predicted the risk of multiple falls in patients over 65 in a study (Kiel, 2020).

Those who report multiple falls, describe gait or balance difficulties (either by report or as evidenced by the brief evaluation described above), or seek care due to injuries suffered during a fall should undergo a multifactorial fall risk assessment. This evaluation should include reviewing the patient's medical history, including their current medications, history of falls, footwear use, and environmental hazards. The patient's activity at the time of their fall, any prodromal symptoms, and when and where the fall occurred are essential aspects of a fall history. Dizziness or loss of consciousness may indicate orthostatic hypotension, cardiac disease, or neurological disease. The physical exam should include a cognitive and functional assessment, including gait, balance, and mobility screenings; vision and hearing screening; assessment for cognitive, sensory, or neurological impairment; muscle strength and foot assessment; and cardiac screening to determine rate/rhythm and postural hypotension. A validated tool, such as the Downtown Fall Risk Index, can establish fall risk for patients within various health facility settings but has not been standardized for non-health facility settings (Kiel, 2020).

Basic laboratory testing (i.e., hemoglobin, serum urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, and vitamin D) may help identify patients with dehydration, anemia, or autonomic neuropathy related to DM (Kiel, 2020). Additional physical exam components should include:

- postural vital signs (to assess for postural hypotension)

- a visual acuity screening using a Snellen chart

- an auditory acuity test, such as the whisper test or a hand-held audiometer (VII cranial nerve deficits can lead to vestibular dysfunction)

- an inspection of the extremities for foot or joint deformities (bunions, callouses, or arthritic joint deformities)

- a neurological examination to assess lower extremity strength, sensation, gait, and postural stability (sensory neuropathies and lower extremity weakness increase the risk of falls; Kiel, 2020)

Imaging studies (e.g., brain or spine imaging, echocardiography) or cardiovascular diagnostics (e.g., rate/rhythm monitoring via a Holter or similar wearable monitor) should be recommended on a case-by-case basis concerning findings obtained during the history and physical exam; they are not performed routinely for all patients with a fall history. An echocardiogram may be reasonable for a patient with an audible murmur. At the same time, a spine or brain MRI may be appropriate for a patient with gait and neurological abnormalities, lower extremity spasticity, or reflex abnormalities (Kiel, 2020).

Cognition

The incidence of dementia increases with age, especially after the age of 85. A thorough history with a brief cognitive screening serves as an adequate cognitive evaluation for an older patient. A 2020 systematic review by Hemmy and colleagues aimed to establish the sensitivity and specificity of several common cognitive screens as listed in Table 2. While the evidence was limited, they confirmed that the available screens were highly sensitive and specific for distinguishing dementia from normal cognition. However, the screens’ accuracy was diminished when distinguishing mild dementia from normal cognition and dementia from mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The group found that existing studies were small in scale, and direct comparisons were lacking (Hemmy et al., 2020).

Positive screening should prompt additional evaluation. Medical conditions that may be treatable should be ruled out, including vitamin B12 deficiency, thyroid dysfunction, depression, and numerous brain or neurological disorders. If indicated, detailed neuropsychological testing should be completed by a licensed neuropsychologist or clinical psychologist. Imaging studies (magnetic resonance [MRI] or computed tomography [CT]) and referral to a neurologist or gerontologist should also be considered (Ward & Reuben, 2020).

For additional information regarding the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of dementia, please refer to the NursingCE course on Alzheimer's Disease: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Research.

Most dementia patients exhibit a slow and steady cognitive decline over months with intact attention and remote memory despite impaired short-term memory, judgment, confusion, and disorientation. Dementia patients may experience paranoia and hallucinations, although these events are rare (Lippmann & Perugula, 2016). In contrast, cognitive impairment associated with attention deficit that develops over hours or days may indicate delirium, which can be difficult to distinguish from dementia. A key feature that defines delirium, or acute confusional state, is a high likelihood that the patient's acute cognitive change is related to a medical condition, medication, or substance use or withdrawal. It typically persists for days but may last for months if the underlying cause is not correctly identified and treated quickly. Symptoms often worsen throughout the day, peaking in the evening. In older patients who are acutely ill, cognitive and behavioral changes may be the only noticeable symptom of their underlying illness. Psychomotor disturbances (e.g., hypoactivity or hyperactivity), sleep disturbances, emotional disturbances, hallucinations, and delusions often accompany delirium. Individuals with underlying brain disorders (e.g., dementia, Parkinson's disease, or stroke) are at increased risk for delirium. Other risk factors include age and sensory impairment. Patients initially may appear easily distracted and, in more advanced cases, present as lethargic, drowsy, or nearly comatose. They often exhibit memory loss, disorientation, and speech or language abnormalities (Francis & Young, 2020).

The 2019 BC lists several high-risk medications based on moderate-quality evidence regarding delirium risk in older patients. This list includes benzodiazepines, nonbenzodiazepine receptor agonists (non-BZRAs or Z-drugs, such as zolpidem [Ambien], zaleplon [Sonata], and eszopiclone [Lunesta]), anticholinergics, antipsychotics, corticosteroids, and meperidine [Demerol]. The level of evidence supporting the avoidance of histamine 2-receptor antagonists (H2 blockers) was reduced to low quality (AGS Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel, 2019; Fixen, 2019). Certain antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolones, penicillins, macrolides, aminoglycosides, cephalosporins, sulfonamides, metronidazole [Flagyl], linezolid [Zyvox], rifampin [Rifadin]), antifungals (e.g., amphotericin B [Amphocin]), antivirals (e.g., acyclovir [Zovirax]), and antimalarials may induce or prolong delirium. Otherwise, the prevention of delirium can be difficult. Additional medications that are considered high-risk for delirium development include AEDs (e.g., carbamazepine [Tegretol], phenytoin [Dilantin], levetiracetam [Keppra]), SSRIs, TCAs, beta-blockers, diuretics, antiarrhythmics, muscle relaxants, dopamine agonists (e.g., levodopa [Sinemet], ropinirole [Requip], amantadine [Symmetrel]), antiemetics, antispasmodics, barbiturates, and cholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., donepezil [Aricept]; Francis, 2019, Table 1).

For additional information on the diagnosis and management of delirium, please refer to the NursingCE course on Management of Common Geriatric Syndromes, Part 1.

Mood Disorders

Depression in the geriatric patient population increases suffering, impairs functional status, increases mortality risk, and increases the consumption of healthcare resources. Geriatric depression may involve atypical symptoms, leading to underdiagnosis and undertreatment. Cognitive impairment can complicate the assessment of a mood disorder. A simple screening (see Table 3) improves the diagnostic process and should be easy to administer. The Two-Question Screener asks the patient if they have been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless or noticed a lack of interest or pleasure in doing things previously enjoyed in the last month (i.e., anhedonia; Ward & Reuben, 2020). Older adults with depression may present with a lack of response to standard medical treatment for an unrelated condition, poor motivation to participate in their medical care, somatic symptoms that are more severe than expected, or decreased engagement with the healthcare team. For those older than 85, a dysphoric mood is a less reliable indicator of depression (Espinoza & Unutzer, 2019).

The Two-Question Screener and PHQ-2 are nearly identical, except that the screener refers to a duration of 1 month, while the PHQ-2 refers to the last 2 weeks (Espinoza & Unutzer, 2019). If both of the questions in the PHQ-2 are answered affirmatively by the patient, the remaining seven questions that make up the PHQ-9 can be completed to improve the screen's specificity (Ward & Reuben, 2020). The PHQ-9 is a self-administered scale based on the diagnostic criteria for depression in the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). It results in a score ranging from 0 to 27, with 5 representing mild depression. A score above 10 indicates major depression, while a score above 20 indicates severe depression (Kroenke et al., 2001). The GDS varies somewhat in sensitivity and specificity depending on the version being used (5-item or 15-item versions). The time to administer is significantly reduced (1 minute) with the 5-item version (Hoyl et al., 1999). Positive screening is defined as two out of five depressive responses ("no" to the first question and "yes" to the remaining four questions; Espinoza & Unutzer, 2019). The Cornell Scale is the only instrument validated for cognitively impaired patients (Ward & Reuben, 2020). It includes direct responses from the patient as well as observer data. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale is commonly utilized in primary care and community studies (Espinoza & Unutzer, 2019).

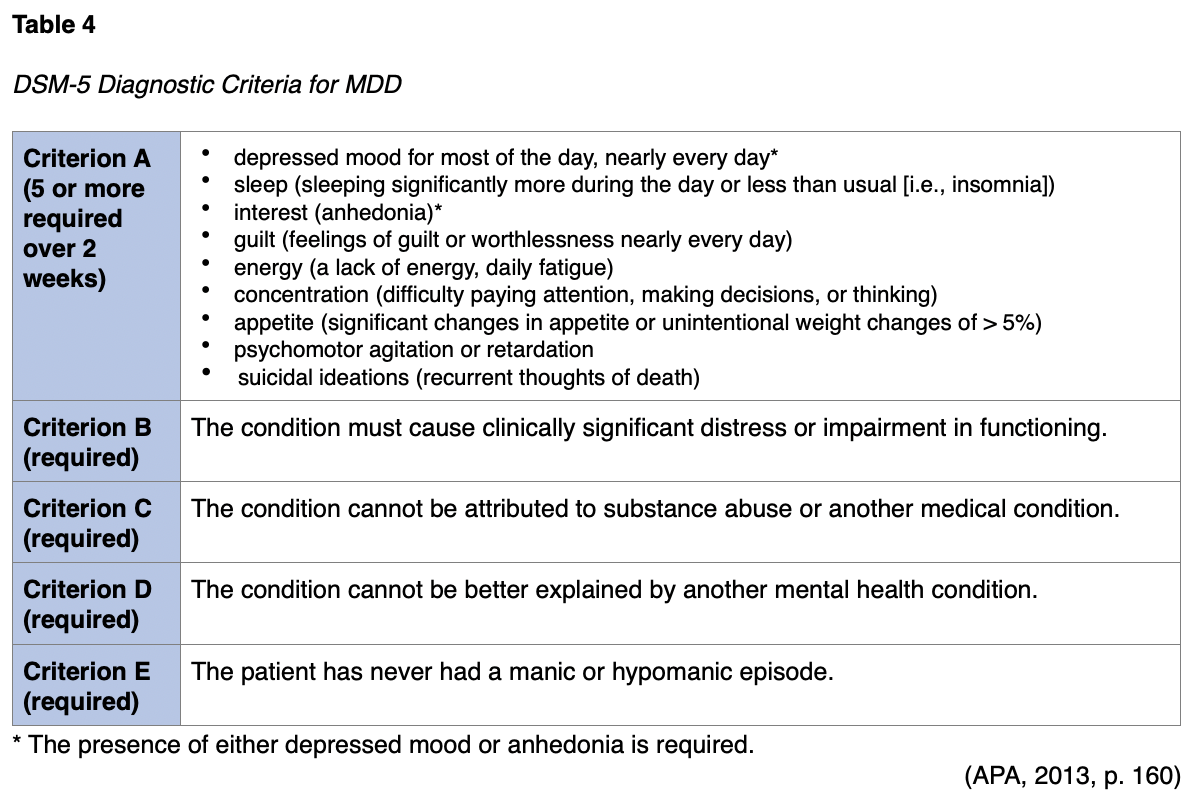

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a clinical diagnosis based on the diagnostic criteria found in the most recent APA (2013) diagnostic manual, the DSM-5. For a patient to be diagnosed, they should demonstrate at least 5 of the 9 symptoms listed in Criteria A for at least 2 consecutive weeks, and at least 1 of these must be a depressed mood or anhedonia (APA, 2013). A common mnemonic to remember the other symptoms included in Category A is "SIG E CAPS," as shown in Table 4.

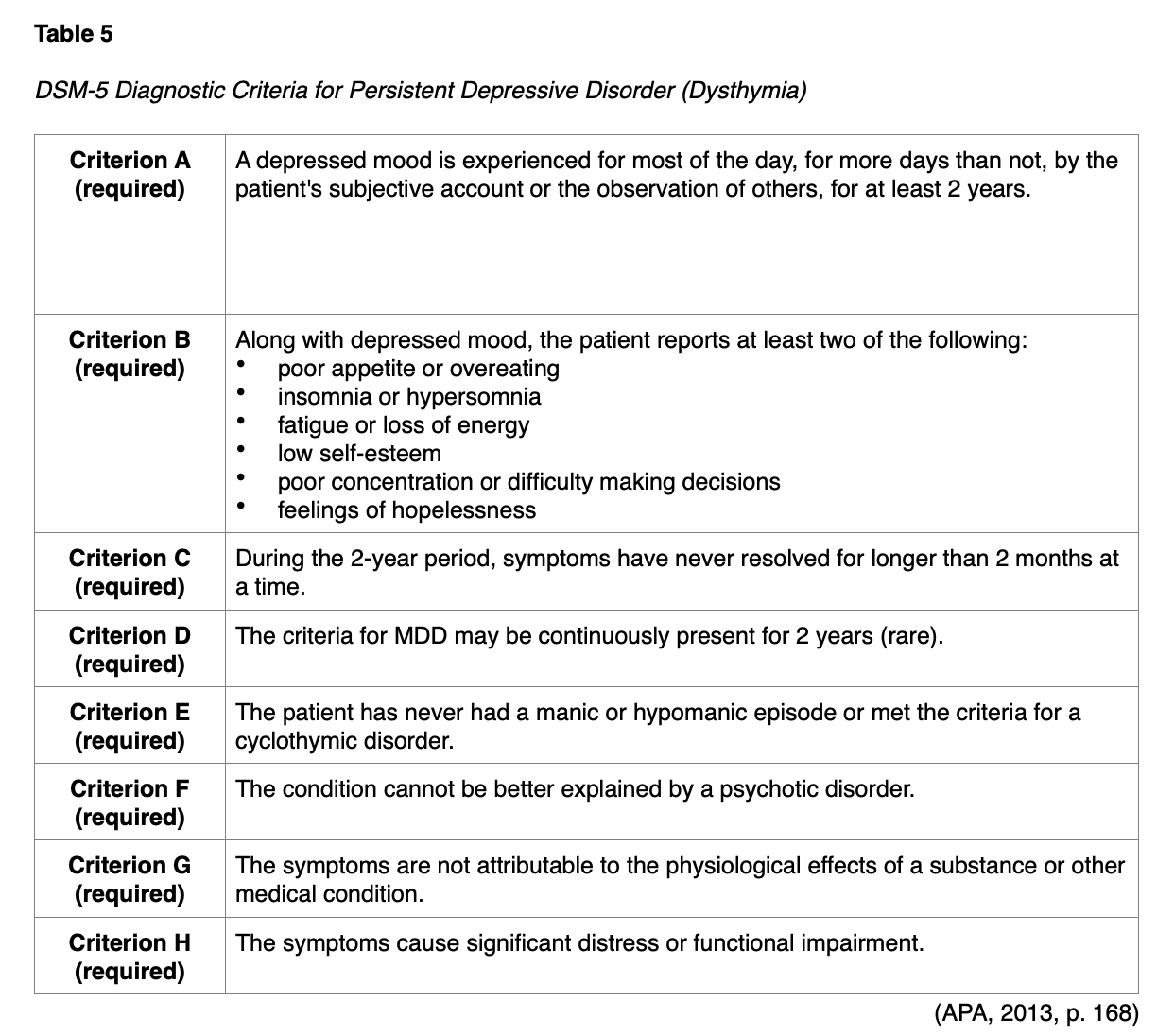

The diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode (MDE) mirror criteria A-C of MDD, as detailed in Table 4. Differential diagnoses that should be considered include manic episodes (e.g., bipolar depression), an underlying medical condition or substance use disorder (SUD) contributing to the mood disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, adjustment disorder, and expected periods of sadness, which unfortunately are "inherent aspects of the human experience" (APA, 2013, p. 168). If symptoms persist for 2 years (with asymptomatic periods of no more than 2 months), the patient qualifies for persistent depressive disorder or dysthymia, as shown in Table 5 (APA, 2013).

For patients with depressive symptoms that do not rise to the level of the diagnostic criteria for MDD, an MDE, or dysthymia, the DSM-5 allows for the diagnosis of minor or subsyndromal depression, classified as other specified depressive disorder. These conditions are more common among older adults than MDD or MDE. The diagnosis of minor or subsyndromal depression requires the patient to experience a depressed mood and at least one other symptom listed in Criterion A for MDD/MDE (Table 4) for at least 2 weeks (APA, 2013, p. 183). Grief, which is also common in older adults, can be challenging to distinguish from MDD or an MDE. Feelings of emptiness and loss characterize grief, and dysphoria occurs in varying intensity (associated with reminders of the departed) but typically decreases over time. These "waves" or "pangs" of grief tend to be interspersed by periods of humor or positive emotions. Thoughts tend to focus on the deceased and joining them, but suicidal ideations are uncommon. While guilt is expected regarding actions or lack of actions associated with the deceased, the self-esteem of the bereaved is preserved. By contrast, the dysphoria demonstrated by someone with MDE/MDD is consistent, and thoughts tend to be self-critical and pessimistic. Feelings of worthlessness and thoughts of suicide are common (APA, 2013).

All older adults with mood disorder concerns should be evaluated for any suicidal ideations or intent, psychotic symptoms (delusions, hallucinations), hopelessness, insomnia, and malnutrition. A history of prior depressive episodes or symptoms should be explored, along with any treatments and their effectiveness. Having a first-degree relative with depression increases a person’s risk of depression, so family history should also be reviewed. The patient's medication list should be assessed for drugs that often exert depressant side effects, such as CNS depressants (e.g., benzodiazepines) and pain medications (e.g., opiates; (Espinoza & Unutzer, 2019). Other medications associated with depressive symptoms include corticosteroids, ACE inhibitors, and lipid-lowering agents (Kok & Reynolds, 2017). The patient should be assessed for SUD and medical conditions associated with depression, such as thyroid disease and DM. Although adults over age 65 account for roughly 13% of the US population, they comprise nearly 24% of completed suicides. The suicide rate is highest among older men, especially over the age of 85. Acute indications of suicide risk include hopelessness, insomnia, agitation, restlessness, poor concentration, psychotic symptoms, SUD, and untreated pain (Espinoza & Unutzer, 2019).

For additional information regarding the management of depression in older adults, please refer to the NursingCE courses on Depression and Management of Common Geriatric Syndromes, Part 2. For additional information regarding suicide, please refer to the NursingCE course on Suicide and Suicide Prevention.

Social and Financial Resources

A brief social history can establish available resources for older adults if they become ill or injured and require additional assistance in the future. A lack of social support often becomes a determining factor in living arrangements and the necessary level of care for older individuals as they develop numerous medical comorbidities and require an increasing level of aid. Preemptive screening can allow additional time for planning and resource referral. An essential physical examination to identify suspicious injuries (contusions, burns, bite marks, pressure injuries, or malnutrition) can flag potential cases of elder physical abuse or neglect (Ward & Reuben, 2020). Other than unexplained injuries, red flags indicating older adult abuse include SUD in a caregiver, limited social support, observed changes in patient behavior when in the presence of the caregiver, or poor compliance with filling and administering prescribed medications. As with all cases of potential abuse or neglect, the patient should be asked objective, open-ended, and nonjudgmental questions in a private setting, not in front of the caregiver in question (Agarwal, 2020).

Self-neglect among older adults is defined as the "refusal or failure to provide oneself with care and protection in areas of food, water, clothing, hygiene, medication, living environments, and safety precautions" (Dong, 2017, p. 1). In the US, self-neglect is determined to be the underlying cause of roughly 40% of neglect cases reported to Adult Protective Services (APS). The prevalence is difficult to estimate due to a paucity of research on the topic, variable operational definitions, and inadequate measurement methods. The Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP), which included 5,519 total study participants, found a self-neglect prevalence of 21% among African American participants and 5.3% among European Americans. The 2010 Elder Justice Act (EJA) defines self-neglect as "the inability, due to physical or mental impairment or diminished capacity, to perform essential self-care" (Dong, 2017). For additional information regarding self-neglect in older adults, please refer to the NursingCE course on Management of Common Geriatric Syndromes, Part 2.

If caregivers accompany a patient, they should be screened regularly for burnout and referred for local resources such as respite care, support groups, and counseling. A financial assessment can be crucial in identifying unknown or previously untapped resources for an older patient in need, such as state or local benefits, long-term care insurance, or veteran's benefits. The multidisciplinary CGA team should include an LSW who is familiar with available resources and access methods. The LSW should evaluate the patient's current financial situation and assess for additional resources if needed (Ward & Reuben, 2020). An LSW also can address social isolation, patient and family education, advanced care planning, and referrals to community or mental health resources (Agarwal, 2020).

For additional information regarding the assessment, diagnosis, and care of victims of elder abuse, please refer to the NursingCE course on Domestic and Community Violence.

Goals of Care

Patients and their families should be central throughout the CGA process; most importantly, they should be allowed to prioritize their outcomes along the way. This health wish list of future achievements or goals often includes regaining a vital skill (e.g., walking without the aid of a device). A patient’s goals are often social (e.g., attending a grandchild's graduation or wedding, living at home) or functional (e.g., independence with ADLs) and less often directly health-related (e.g., to lose 10 pounds, to decrease SBP below 140). Goals should be both short- and long-term, as well as personalized. Progress should be monitored regularly to track whether goals have been met or to modify goals if needed. A formal method for establishing and monitoring goals may be used; the Goal Attainment Scale (GAS) is a free tool that utilizes patient-reported outcomes (Ward & Reuben, 2020). Each patient determines their outcome measures, and their definition of success is agreed upon at the outset. The score is calculated using a 5-point scale for each goal, ranging from +2 (patient achieved much more than expected) to -2 (patient achieved much less than anticipated; Shirley Ryan Abilitylab, 2020).

Advance Care Preferences

To differentiate from discussions regarding goals of care, documenting a patient's advance care preferences involves determining which interventions they find acceptable and who should make future healthcare decisions for the patient if their health deteriorates and precludes them from making such decisions themselves. These discussions should occur while the patient has the mental faculties needed to participate fully and articulate their wishes. Patients should be asked about specific interventions designed to extend life (e.g., feeding tubes, intubation, ventilator support), how their preferences may change if their medical team advises against further aggressive or curative treatments, and how decisions should be made if current caregivers become overwhelmed and cannot care for the patient in their current environment. Formal tools have been developed to assist providers in facilitating discussions about end-of-life care and promote shared decision-making (Ward & Reuben, 2020). Due to their extensive skills in this area, an LSW should be recruited to assess and then address advanced-care planning concerns with each patient during the CGA process (Agarwal, 2020).

Polypharmacy

The performance of thorough medication reconciliation and medication review is an essential component of the CGA. Roughly one-half (44% of men and 57% of women) of those over the age of 65 take at least five medications (prescription or OTC) every week. In this same age group, 12% of patients take at least 10 medications. National treatment guidelines for chronic conditions may dictate that patients be prescribed a minimum of six medicines to reduce their risk of long-term complications related to DM, coronary artery disease, etc. However, polypharmacy becomes an issue if it contributes to negative outcomes, such as adverse events, noncompliance, and increased cost (Saljoughian, 2019). Polypharmacy has been established as an independent risk factor for hip fractures in older adults (Rochon, 2020). Being prescribed various medications by multiple HCPs increases the risk of adverse events and drug-drug interactions for older adult patients. Polypharmacy also leads to therapeutic duplication, unnecessary medications, and poor adherence. Risk factors for polypharmacy include age, education, ethnicity, health status, and access to a pharmacy (Nguyen et al. 2020; Ward & Reuben, 2020). The risk of a drug-drug interaction rises as the number of medications increases. A patient taking 5-9 different medications has a 50% chance of an interaction, but this probability increases to 100% in a patient taking 20 or more medications. While polypharmacy increases the risk of poor adherence, geriatric patients may also have difficulty with forgetting to take their medications, poor vision, limited financial resources, and limited access to a pharmacy or transportation to a pharmacy, all of which have been shown to reduce medication regimen adherence. Patients may also elect to reduce the dose or stop a medication if they perceive an unpleasant symptom caused by the medication (Saljoughian, 2019).

For a complete discussion regarding polypharmacy in older adult patients, including how to address this issue and age-specific prescribing considerations for older adults, please see the Nursing CE course Care Considerations for Older Adults: The Assessment and Management of Polypharmacy

Outcomes

Research has confirmed that the CGA process leads to enhanced detection and documentation of geriatric problems and syndromes. Outcomes such as decreased hospitalization rate, skilled nursing facility (SNF) admission, and mortality vary based on the setting and specific CGA model used. Settings that have been studied include home assessments, acute geriatric units, post-hospital discharge, outpatient consultations, and inpatient consultations (Ward & Reuben, 2020).

Home geriatric assessments are typically led by a nurse and consist of a PT, LSW, and psychologist who focuses on preventative as opposed to rehabilitative services. Patients generally are followed for a year, and telephone follow-ups are standard. Many homebound or home-limited older adults have not received an in-home assessment. Home CGAs reduce functional decline and mortality but not admissions to LTC facilities (Ward & Reuben, 2020).

Acute geriatric care units are referred to as Geriatric Evaluation and Management Units (GEMUs) in US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospitals or Acute Care of the Elderly (ACE) units in private hospitals. These units are typically staffed by clinicians who assume primary care for the patient, implementing recommendations seamlessly, and a skilled team of professionals (e.g., nurses, PT, OT, SLP, LSW) who tailor care to the older adult population and enhance consistency (Ward & Reuben, 2020). This model of care is designed to prevent the prolonged functional decline that is typically seen after acute hospitalizations among frail older adults (Walston, 2020). Compared to standard inpatient care, patients who received a CGA as a component of ACE were less likely to be living in LTC facilities and more likely to be living at home a year after hospital admission. Studies have not shown a reduction in dependence, cognitive status, or mortality (Ward & Reuben, 2020).

Post-hospital discharge CGA programs are designed to identify vulnerable patients via multidimensional assessment. Comprehensive discharge planning and home visits with nurses to follow up in the weeks after discharge are supplemented by telephone calls and specialty home visits from PTs, OTs, LSWs, or additional nursing visits if indicated. These CGAs should be initiated a day or two before discharge. The research on the effectiveness of post-discharge CGAs is mixed, although it may reduce the hospital readmission rates, cost, and ED visits. Programs designed for patients discharged from the ED can reduce future ED visits and hospital admissions (Ward & Reuben, 2020).

Outpatient CGA programs may be beneficial, but only when they address adherence to program recommendations and focus on patients at increased risk of hospitalization. These programs may reduce functional decline, fatigue, depression, and the use of health services. The Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE) program incorporates an APRN into the interdisciplinary care team. This measure has reduced ED visits and hospitalizations and improved QOL for low-income seniors. The Guided Care program, which incorporates a specially trained RN into the primary care team for chronically ill high-risk patients, showed a reduction in home health care episodes, LTC admissions, and days of hospitalization for some patients. Practice redesign approaches that focus on specific conditions may improve the quality of care for falls, incontinence, and dementia (Ward & Reuben, 2020).

Inpatient CGA programs have shown little to no long-term benefit in patient outcomes. However, comanagement surgical programs with a geriatrician may reduce complications, delirium, mortality, and rehospitalization for patients after a hip fracture. Similar programs have resulted in reduced length of stay and inpatient postoperative mortality. Patients who participate in a CGA program after hip fracture were less likely to be discharged to an LTC or assisted living facility (Ward & Reuben, 2020).

References

Agarwal, K. (2020). Failure to thrive in older adults: Evaluation. UpToDate. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/failure-to-thrive-in-older-adults-evaluation

American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. (2019). American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(4), 674–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15767

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

Bohannon, R. W. (2006). Reference values for the timed up and go test: A descriptive meta-analysis. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy, 29(2), 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1519/00139143-200608000-00004

Brown-O’Hara, T. (2013). Geriatric syndromes and their implications for nursing. Nursing2021, 43(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000423097.95416.50

Christensen, B. (2018). Karnofsky performance status scale. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2172510-overview

Dalhousie University. (2020). Clinical frailty scale. https://www.dal.ca/sites/gmr/our-tools/clinical-frailty-scale.html

Dong, X. Q. (2017). Elder self-neglect: Research and practice. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 12, 949-954. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S103359

Espinoza, R. T., & Unutzer, J. (2019). Diagnosis and management of late-life unipolar depression. UpToDate. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-and-management-of-late-life-unipolar-depression

Fixen, D. R. (2019). 2019 AGS Beers Criteria for older adults. Pharmacy Today, 25(11), 42-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptdy.2019.10.022

Francis, J. (2019). Delirium and acute confusional states: Prevention, treatment, and prognosis. UpToDate. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/delirium-and-acute-confusional-states-prevention-treatment-and-prognosis

Francis, J., & Young, G. B. (2020). Diagnosis of delirium and confusional states. UpToDate. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnosis-of-delirium-and-confusional-states

Frith, K. H., Hunter, A. N., Coffey, S. S., & Khan, Z. (2019). A longitudinal fall prevention study for older adults. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 15(4), 295-300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpa.2018.10.012

Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing. (n.d.). Try This: series. Retrieved February 5, 2021, from https://hign.org/consultgeri-resources/try-this-series

Hemmy, L. S., Linskens, E. J., Silverman, P. C., Miller, M. A., Talley, K. M. C., Taylor, B. C., Ouellette, J. M., Greer, N. L., Wilt, T. J., Butler, M., & Fink, H. A. (2020). Brief cognitive tests for distinguishing clinical Alzheimer-type dementia from mild cognitive impairment or normal cognition in older adults with suspected cognitive impairment. Annals of Internal Medicine, 172(10), 678–687. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-3889

Hoyl, M. T., Alessi, C. A., Harker, J. O., Josephson, K. R., Pietruszka, F. M., Koelfgen, M., Mervis, J. R., Fitten, L. J., & Rubenstein, L. Z. (1999). Development and testing of a five-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 47(7), 873–878. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb03848.x

Kiel, D. P. (2020). Falls in older persons: Risk factors and patient evaluation. UpToDate. Retrieved February 9, 2021, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/falls-in-older-persons-risk-factors-and-patient-evaluation

Kok, R. M., & Reynolds, C. F. (2017). Management of depression in older adults: A review. JAMA. 317(20), 2114-2122. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.5706.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Lippmann, S., & Perugula, M. L. (2016). Delirium or dementia? Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 13(9-10), 56–57.

Min, L., Yoon, W., Mariano, J., Wenger, N. S., Elliott, M. N., Kamberg, C., & Saliba, D. (2009). The Vulnerable Elders-13 Survey predicts 5-year functional decline and mortality outcomes among older ambulatory care patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57(11), 2070–2076. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02497.x

Nguyen, T., Wong, E., & Ciummo, F. (2020). Polypharmacy in older adults: Practical applications alongside a patient case. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 16(3), 205–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2019.11.017

Rochon, P. A. (2020). Drug prescribing for older adults. UpToDate. Retrieved February 11, 2021, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/drug-prescribing-for-older-adults

Rockwood, K., Song, X., MacKnight, C., Bergman, H., Hogan, D. B., McDowell, I., & Mitnitski, A. (2005). A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 173(5), 489–495. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050051

Rockwood, K., & Theou, O. (2020). Using the clinical frailty scale in allocating scarce health care resources. Canadian Geriatrics Journal, 23(3), 210–215. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.23.463

Saljoughian, M. (2019). Polypharmacy and drug adherence in elderly patients. US Pharmacist, 44(7), 33-36. https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/polypharmacy-and-drug-adherence-in-elderly-patients

Shirley Ryan Abilitylab. (2020). Goal attainment scale. https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures/goal-attainment-scale

Tagliareni, E., Cline, D. D., Mengel, A., McLaughlin, B., & King, E. (2012). Quality care for older adults: Advancing Care Excellence for Seniors (ACES) project. Nursing Education Perspectives, 33(3), 144-149. https://doi.org/10.5480/1536-5026-33.3.144

Voelker, R. (2018). The Mediterranean diet’s fight against frailty. JAMA, 319(19):1971–1972. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.3653

Walston, J. D. (2020). Frailty. UpToDate. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from www.uptodate.com/contents/frailty

Ward, K. T., & Reuben, D. B. (2020). Comprehensive geriatric assessment. UpToDate. Retrieved February 5, 2021, from www.uptodate.com/contents/comprehensive-geriatric-assessment