About this course:

The purpose of this activity is to enable the learner to understand the progression of HIV or AIDS, how to care for and treat patients impacted by the disease, and to further satisfy the state requirement for healthcare providers to complete a seven-credit course.

Course preview

Course Objectives:

- Define HIV and AIDS and understand the impact in the US and globally.

- Discuss the stages of HIV.

- Discuss HIV testing and the required counseling.

- Identify the factors that affect transmission and methods to decrease the risk of HIV infection.

- Consider occupational exposures to bloodborne pathogens and the risks to healthcare providers.

- Explore the clinical manifestations and treatment of HIV/AIDS.

- Consider the legal and ethical issues related to HIV/AIDS, including confidentiality.

- Explore the psychosocial issues surrounding HIV/AIDS, including special population considerations.

Introduction

The diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) was considered a death sentence just a few decades ago when the disease first came to light in the US and around the world. Today's prognosis has significantly improved, and this module will explore the current data relevant to HIV infection and the outcomes for those diagnosed with AIDS (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2017b). HIV is a diagnosis that many nurses will see across various practice areas. A clear understanding of the implications of HIV infection in specific populations, co-infections, and management of this disease is essential for all healthcare providers.

Epidemiology and Etiology

History of HIV

Although current data shows that HIV started infecting humans in the 1970s, scientists were not aware of the virus for a decade afterward. Beginning in the early 1980s, new illnesses were emerging throughout the world. Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), a reasonably harmless cancer that was previously common among the elderly, started appearing as an aggressive strain in younger patients. At the same time, rare and aggressive types of pneumonia began appearing in another group of patients. By 1981, scientists had connected the dots between these two new diagnoses, in addition to other opportunistic infections that were emerging. By the end of 1981, the first case of AIDS was documented in the medical literature. In the early 1980s, a new disease emerged in New York and Los Angeles among gay men. Even though these separate events were occurring simultaneously, the connection was not made. Scientists were aggressively working to figure out the poorly understood new killer. It was noted early in 1981 that young, homosexual men were being diagnosed with HIV and that the virus was likely sexually transmitted or caused by dirty needles. Consequently, HIV was labeled as a "gay-related illness", immediately stigmatizing the diagnosis. However, other early events such as the AIDS outbreak in Haiti, the identification of hemophiliac patients as an at-risk population, and mother-child transmission in utero served to inspire doctors and scientists to focus on blood borne transmission in addition to sexual transmission as possible etiologies. The stigmatization, however, did not disappear quickly. Television evangelist Jerry Falwell announced that God had sent AIDS as retribution for sins of drug users and the gay community. HIV/AIDS patients were ostracized due to mass hysteria, and a young HIV-positive hemophiliac student, Ryan White, was expelled from middle school (Public Health, 2019).

Public policy responded by closing down gay nightclubs and bathhouses. Law enforcement officers were issued masks and gloves to protect them from exposure to the virus, and needle exchange programs began to address the concerning trend of the reuse of needles among drug users. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) started to consider the safety of the nation's blood bank after a post-partum female was diagnosed with AIDs just months after her delivery and subsequent blood transfusions. In 1985, the first International AIDS meeting met as the disease was appearing across the globe. By 1986, the first antiretroviral (ARV) drug, zidovudine (Retrovir, AZT), was introduced through clinical trials in the US. Zidovudine (Retrovir, AZT) was initially developed as a chemotherapy drug but produced beneficial results during the clinical trials for HIV patients. The results were so promising that the FDA halted the trials, stating that it would be unethical to deprive the patients who were getting placebos of the actual drug (Public Health, 2019).

By 1993, there were over 2.5 million cases of HIV/AIDS worldwide, and by 1995, it was the leading cause of death for Americans between the ages of 25 and 44. The United Nations (UN) reported that in 1996, there were over 3 million new cases in patients under 25 years of age. The rate of death did not slow down until 1997. During this time, legislation moved forward in the US, including legally prohibiting HIV positive individuals from working in healthcare settings, donating blood, entering the country on a travel visa, or immigrating to the US. Simultaneously, new drugs were being studied, including ACTG 076 (subsequently named zidovudine), saquinavir (Invirase), and nevirapine (Viramune). Combination therapy approaches demonstrated success during this time, and by 1997, a global standard of care for treatment was in place. Prevention techniques were identified, including condom use. The condom was rarely discussed before the HIV/AIDS era, yet it has become a mainstay for prevention since inception. President Clinton aggressively advocated for HIV/AIDS education and many resources were allocated toward AIDS research during his eight-year term. Additionally, the World Health Organization (WHO) AIDS program was replaced by the UN AIDS Global Programme that is still in place in today (Public Health, 2019).

While all of the above described progress was occurring in the US and other developed parts of the world, there was an outbreak in Africa. Since AIDS was initially considered an illness among the gay population, many African leaders ignored the disease and refused to recognize that sex between men occurred in their country. In many countries, homosexuality was still a crime, and early AIDS activists supporting treatment were jailed in Africa. Since the homosexual population was forced to operate underground, an open campaign against HIV/AIDS was not possible and reaching those who needed treatment was nearly impossible. By 2003, AIDS overtook the African population with almost 40% of Botswana's adult population infected with HIV and similar percentages in Swaziland. By 2010, nearly 40 million children had lost one or both parents to the AIDS epidemic. Unfortunately, even after heterosexual infection became apparent, education and treatment remained slow to gain footing due to the continued stigma (Public Health, 2019).

HIV has continued to spread across the globe since 2000. Heroin addiction in Asia was on the rise and added to the infection rate through the use of dirty needles. To date, India's government refuses to admit there is an HIV epidemic in their country despite over 2 million new confirmed cases since 2000. In a comprehensive report in 2010 that examined HIV/AIDS over the previous 25 years, developing nations showed progress in the number of new infections and the mortality rate. The US infection rate stabilized by 2008, which continues through present day. Unfortunately, there are still many people impacted by HIV/AIDS. The 2010 report further showed a reduced incidence rate in other developed countries, but continued problems in underdeveloped countries. South African leaders continued to deny the issue of HIV infection, despite an estimated 16.9% of South Africans aged 15-25 that were HIV positive in 2008. Uganda, who has taken steps to address the epidemic, has seen their HIV infection rate decreased dramatically over ten years. This success has helped to facilitate other African countries to develop policies to overcome the taboos of sex education

...purchase below to continue the course

Incidence and Prevalence

There are approximately 1.1 million people in the US living with HIV, and approximately 15% (1 in 7) are unaware that they are infected (CDC, 2019b). In 2016, almost 39,000 Americans were newly infected with HIV, and gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men represent 26,000 of those new cases. New cases are unequally distributed across the US, with over 50% occurring in the South. The states with the highest HIV risk include Washington D.C., Maryland, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, New York, Texas, New Jersey, Mississippi, South Carolina, North Carolina, Delaware, and Alabama. The CDC notes that an American has a 1 in 99 chance of contracting HIV in their lifetime (CDC, 2019b).

In 2013, the US had a total of 4,110 deaths from AIDS, and more than half were African American. Most cases among women are from heterosexual sex, and the number of women with new HIV diagnoses across the US has declined between 2005 and 2014 by nearly 40%. Due to positioning, (receptive sex) women are at a higher risk of contracting HIV during sex (CDC, 2015).

The CDC (2015) reported that 22% of all new HIV diagnoses in the US in 2004 were between the ages of 13 and 24. The vast majority (80%) of those cases were young, gay, and bisexual males, and most were African American or Hispanic. The same timeframe saw 1,716 youth with a diagnosis of AIDS and was 8% of the total number of AIDS cases in 2014. This group is unlikely to seek testing, practice prevention, begin antiretroviral therapy, or risk reduction. Some of the prevention challenges for youth are inadequate sex education, high risks for other STIs, the stigma associated with the disease, and feelings of isolation.

Between 2010 and 2016, the number of HIV infections decreased among 13-24-year-olds and 45-54-year-olds but increased among the 25-34-year-old group. There was a steady number of HIV infections among those aged 33-44 and those over the age of 55. When considering race, the incidence among African Americans, whites, and multiracial individuals decreased, but new infections remained stable for Asians and Hispanics. Infections decreased among females during this same timeframe but remained steady in males (CDC, 2015).

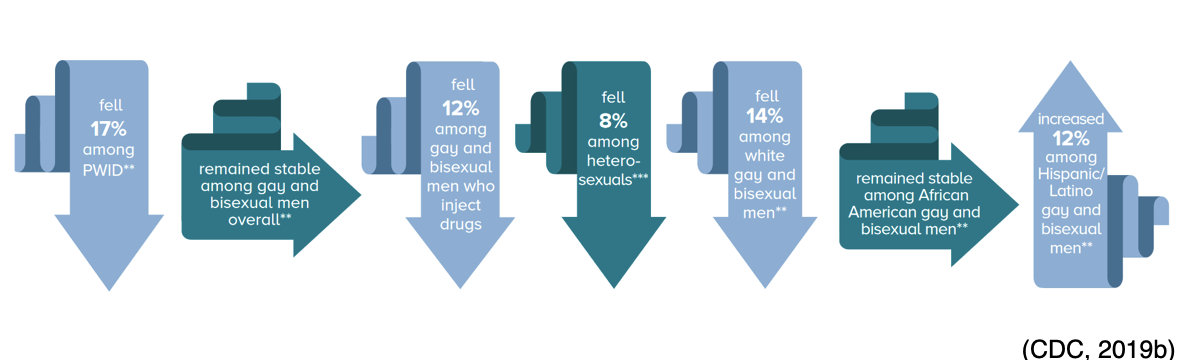

HIV infections decreased during the 2010-2016 timeframe in heterosexuals and persons who inject drugs (PWID) yet remained stable among those with male-to-male sexual contact. Incidence rates increased among Hispanic gay and bisexual men but decreased among white gay and bisexual men. See Figure 1 below for more details (CDC, 2019b; Minority HIV/AIDS Fund, 2019b).

Figure 1: HIV in the US and Dependent Areas

WHO estimates that approximately 36.7 million people were living with HIV worldwide by the end of 2015. Currently, there is no cure for HIV, but the disease is treatable with proper antiretroviral therapy (ART) discussed later in this module. In addition to medication, secondary prevention can prolong an infected person's life dramatically and avoid spreading the disease to others. The patient and caregivers must remember that HIV is a life-long disease (CDC, 2017a).

What Is HIV?

HIV is a virus that attacks the human immune system and limits the body's ability to self-protect against disease and infections. The former healthy immune system of the individual infected with HIV can no longer protect itself from infections or the progression of the virus. HIV targets CD4+ lymphocytes, also known as T-cells or T-lymphocytes. T-cells work in concert with B-lymphocytes as part of the acquired (adaptive) immune system. HIV integrates its RNA into host-cell DNA through reverse transcriptase, reshaping the host’s immune system (CDC, 2017a).

By attaching itself to CD4+ cells, the virus is able to replicate and destroy them, leading to a decrease in the number of CD4+ cells available for normal immune system functioning. The host produces extra CD8 cells to compensate for this loss. If untreated, HIV continues to take over progressively more of the host’s immune response (CDC, 2017a).

HIV infection was originally a single, continuous disease process of three stages but was updated to include a fourth stage when immediate infection with HIV, stage 0 was added. The stages progress from initial infection to the development of AIDS (CDC, 2017a). Therefore, a patient who has HIV does not necessarily have AIDS, but any patient who has AIDS previously acquired the HIV infection. Patients in stage 3 are severely immunocompromised and require complex care. Stages 1, 2, and 3 are determined using the patient’s CD4+ count or the CD4+ percentage when the count is unavailable (see Table 1 below). If neither of these findings is available, the patient is considered "stage unknown." Listed below is an outline of how to appropriately characterize each HIV stage. Of note, the CD4+ counts and percentages are based on patients older than five (CDC, 2017a).

Stage 0

Stage 0 is used to represent early HIV infection. During this time frame, the patient has a negative HIV test, but within six months, the patient will test positive. It is assumed the prior negative test was unable to detect the presence of HIV. The patient can transmit the disease during this time, even though the antibodies titers are negative. It can take up to three months for antibodies to show up on tests, although they typically appear six weeks after exposure (Selik et al., 2014).

Stage 1

The first manifestations of the disease process will occur within four weeks of infection. These manifestations may be mistaken for influenza and can include weakness, fatigue, headache, rash, night sweats, and a sore throat. This stage is marked by a rapid rise in the HIV viral load, decreased CD4+ cell counts, and increased CD8 cell counts. According to the CDC (2017a), individuals in stage 1 will have the three following characteristics:

• Absence of an opportunistic, AIDS-defining condition,

• CD4+ T-lymphocyte count: 500 cells/mm3 or more, and

• CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes: 26% or more.

The resolution of the initial viral manifestations of HIV infection is coincidental with the decline in viral HIV copies. However, lymphadenopathy persists throughout the disease process (CDC, 2017a).

Stage 2

Stage 2 is known as the latency stage, as patients are noted to be asymptomatic due to the decline in viral HIV copies. This decline results from the body's immune system attacking and minimizing the virus, although not eliminating it completely. This stage can be prolonged, allowing patients to remain asymptomatic for ten years or more without taking medication and for decades if on ART. During this stage, anti-HIV antibodies are produced, and the patient’s tests for these will become positive. The viral set point is the amount of virus, or viral load, remaining in the body after the immune system’s efforts to eliminate it. This set point relates directly to the patient's prognosis, as a high viral set point typically equates to poorer outcomes for the patient (CDC, 2017a).

Over time, the virus will use the host's genetic machinery to begin active replication of itself. The viral load increases, and CD4+ cells are destroyed. This process results in a dramatic loss of immunity that can have life-threatening consequences for the patient and are a significant concern to health care delivery. According to the CDC (2017a), this stage has the following characteristics:

• Absence of an opportunistic, AIDS-defining condition,

• CD4+ T-lymphocyte count: 200 to 499 cells/mm3, and

• CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes: 14% to 25%.

As evidenced by the decrease in the CD4+ count and CD4+ percentage as compared to stage 1, the patient is experiencing a significant loss of immunity secondary to the virus becoming more active. This loss of immunity places the patient in a more vulnerable position as they move into the third stage of the disease process (CDC, 2017a).

Stage 3/AIDS

In stage 3 of the disease process, the patient develops AIDS and is at grave risk for opportunistic infections (CDC, 2017a). According to the CDC (2017a), this stage is defined through presentation of the following characteristics:

- Presence of an opportunistic, AIDS-defining condition.

- CD4+ T-lymphocyte count: less than 200 cells/mm3.

- CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage of total lymphocytes: less than 14%.

Patients are considered to be in stage 3 of the disease if an AIDS-defining condition is present, even if the CD4+ count or percentage is outside the expected range. Stage 3 is the final stage of HIV infection, and if the patient does not receive treatment, death is likely to occur within three years. Unlike stage 1 and 2, stage 3 is associated with a range of defining conditions (CDC, 2017a).

As can be seen from the aforementioned description, stage 3 is associated with severe health challenges for the patient, and they are often extremely ill. The nurse should be aware of the pathophysiology of the defining conditions associated with stage 3 to plan appropriate care. Since the patient has the potential to develop more than one AIDS-defining illness, this can present a challenge for the health care team when planning and delivering care (CDC, 2017a).

The following is a list of defining conditions associated with AIDS (stage 3 of the HIV infection), along with a positive HIV test, as outlined by the CDC (2019a):

- Candidiasis of the esophagus, bronchi, trachea, or lungs,

- Herpes simples – chronic ulcers (more than one-month duration),

- Invasive cervical cancer,

- Coccidioidomycosis,

- Cryptococcosis,

- Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal (more than one-month duration),

- Cytomegalovirus diseases (CMV) (particularly retinitis),

- Encephalopathy, HIV-related,

- Bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis,

- Histoplasmosis,

- Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (more than one-month duration),

- Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS),

- Lymphoma, multiple forms,

- Tuberculosis (TB),

- Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) or Mycobacterium kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary. Other Mycobacterium, disseminated or extrapulmonary,

- Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) formerly called pneumocystis carinii pneumonia,

- Pneumonia, recurrent ,

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy,

- Salmonella septicemia, recurrent,

- Toxoplasmosis of brain,

- Wasting syndrome due to HIV (CDC, 2019a).

Table 1: Summary of HIV Infection Progression

Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | |

Presence of an AIDS- defining condition? | No | No | Yes- a range of serious health conditions related to impaired immunity. |

CD4+ T-lymphocyte count: | 500 cells/mm3 or more | 200 to 499 cells/mm3 | Less than 200 cells/mm3 |

CD4+ T-lymphocyte percentage (of total lymphocytes): | 26% or more | 14% to 25% | Less than 14% |

Common disease manifestations: | Flu-like symptoms appear within 2-4 weeks of infection. HIV positive due to anti-HIV antibodies. | May be asymptomatic for 10+ years. Can develop generalized lymphadenopathy. HIV positive due to anti-HIV antibodies. | May develop a range of life-threatening opportunistic infections. |

Disease progression | Viral load rises rapidly. CD4+ cells destroyed. CD8 cells increased. | Viral replication. Viral load increases. Immunity continues to decline. | End stage of HIV infection. AIDS onset. Death within three years when untreated. |

(Assessment Technologies Institute [ATI], 2016)

What is AIDS?

AIDS is a combination of symptoms and infections stemming from an impaired immune system. HIV-infected individuals become vulnerable to diseases or infections known as "opportunistic", as individuals who are not immunocompromised would not be impacted by these illnesses. Modern day medical treatments significantly delay the progression of HIV and subsequent diagnosis of AIDS (USDHHS, 2019b).

As listed above, Stage 3 signals the onset of AIDS and these individuals’ immune systems are severely damaged. The average survival for a patient diagnosed with AIDS is approximately three years if the disease is left untreated. During this stage, the patient’s viral load is very high, making them highly infectious and at high risk for the opportunistic infections listed above, which be discussed at length within the treatment section of this module (CDC, 2019a).

Testing and Counseling

Strains of HIV

There are many strains of HIV due to the high variability of the virus and its mutational capabilities. It is possible for a single person to be infected with multiple strains of the virus. HIV is classified into types, groups, and subtypes with the two primary strains being HIV-1 and HIV-2. The predominant strain worldwide is HIV-1, whereas HIV-2 is less common and found mainly in West Africa. Both strains can progress to AIDS, and both are transmitted through blood and bodily fluids. Each strain has several subtypes and is evolving continuously. HIV testing presently detects all known subtypes as well as the two primary strains (Avert, 2019).

Multidrug-Resistant Forms of HIV

As previously discussed, HIV is skilled at mutating and changing its structure, thereby enhancing drug resistance, which occurs when previously effective medications become ineffective. The nurse should educate the patient to take their medication every day exactly as prescribed. The ARVs prevent HIV from replicating in the blood. When a patient misses a dose of medication, the virus is given an opportunity to replicate and mutate. This process creates a drug-resistant form of the virus, which continues to multiply and spread from person-to-person and limiting the treatment options (Minority HIV/AIDS Fund, 2019a).

Another danger of drug resistance is cross-resistance, which occurs when medications in the same drug class, which work similarly, may prove ineffective against the virus; even when the patient has never taken it before. Cross-resistance can limit the options a patient has for an effective HIV regime (US Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2019a). This topic will be discussed further in the treatment section.

Drug Resistance/Testing for Drug Resistance

HIV drug resistance testing is recommended at the entry of care to guide the selection of the initial ART regime. Genotypic testing is the preferred resistance testing to guide therapy in ART-naïve patients. In pregnant patients or early HIV infection, immediate treatment upon diagnosis is recommended; ART initiation should not be delayed while determining the results of resistance testing. ART can be modified after results are obtained if needed. For patients who have been treated with ART-in the past (ART-experienced), HIV drug resistance testing should be performed to assist in the selection of active drugs when changing ART regimens in patients who have:

- Virologic failure and HIV RNA levels >1,000 copies/mL

- HIV RNA levels >500 copies/mL but <1,000 copies/mL (drug resistance testing may be unsuccessful but should be considered in this group)

- Suboptimal viral load reduction (NIH, 2018).

In order to achieve viral suppression, effective ART is required. For those who do not properly administer ART, the risk of new HIV mutations increases, and the patient is more likely to become frustrated and discontinue treatment (WHO, 2017).

Testing

All testing and results are confidential and cannot be shared with any other individual. Nurses and healthcare providers who provide HIV testing in public health departments or clinical settings must sign strict confidentiality agreements before employment. The agreements regulate the information that can be shared in counseling and testing sessions as well as test results. Written HIV test results must be maintained in locked files, and electronic health records must be password protected and meet standards for security (WSDH, n.d.b). Fifteen percent (1 in 7) of HIV-positive individuals are unaware that they are infected, and for this reason, testing is suggested (CDC, 2019b). Testing is the only verification of infection with HIV. The CDC (2019f) recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 be tested for HIV at least once during routine care. When patients understand their HIV status, it allows them to make fully informed decisions about treatment options and protecting partners. Individuals with a higher risk should be tested more frequently. The CDC (2019f) further recommends that if a patient has not been tested in the last year, the nurse should advise retesting as soon as possible if they answer "yes" to any of the following questions:

- Are you a male that has had sex with another male?

- Have you had anal or vaginal sex with a known HIV-positive partner?

- Have you had more than one sexual partner since being tested for HIV?

- Have you used injectable drugs or shared needles or works (for example, water or cotton) with others?

- Have you been diagnosed or treated for another sexually transmitted infection (STI) since your last test?

- Have you been diagnosed or treated for tuberculosis or hepatitis since your last test?

- Have you had sex with anyone who could answer yes to any of the previous questions or an unknown sexual history? (CDC, 2019f)

Test Types

A diagnosis of HIV infection can involve several steps. Previously, the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was the initial test, and if results were positive, a second test (Western blot or indirect immunofluorescence assay) was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Research and revision to testing strategies have led to more accurate immunoassay tests that are more specific and can accurately confirm the diagnosis sooner. Currently, there are three types of tests used for the diagnosis of HIV infection: nucleic acid tests (NAT), antigen/antibody tests, and antibody tests. These tests use blood, oral fluid, or urine for results (CDC, 2019f).

- The most rapid of the three tests above are antibody tests. Home testing uses this method. The HIV antibody tests identify HIV antibodies in the blood or oral fluids. Antibody tests using blood from a vein can detect HIV sooner than those done with a fingerstick or oral fluids. Rapid antibody screening with a fingerstick or oral fluid can provide results within thirty minutes and is used in most clinical settings. The oral antibody home test kit provides prompt results, typically within twenty minutes. Confidential counseling is available from the manufacturer as well as follow-up testing sites. These kits are available both online and in retail stores. Using a serum home collection kit, the patient pricks their finger and sends the sample by mail to a licensed laboratory for antibody testing. Results are available as quickly as the next day, and the manufacturer provides counseling and referrals for further testing and treatment (CDC, 2019f).

- If any of the rapid antibody tests are positive, follow-up testing is needed to confirm the results. If the first test is performed at home, the second should be done in a healthcare provider's office to verify the results. For initial tests done in a healthcare provider's office, the second is performed in the lab, usually with the same blood sample collected for the initial test (CDC, 2019f).

- The antigen/antibody test will look for both HIV antibodies and antigens. For an HIV-positive patient, the specific antigen is p24. It can be detected very early after exposure to the virus, even before antibody formation. This test is performed in medical labs in the US, and a rapid version is now available (CDC, 2019f).

- The NAT identifies HIV in the blood. If positive, this test can determine the viral load, or the amount of virus in the blood. It is an expensive test and is not recommended for screening except in the case of high-risk exposure or potential exposure with early symptoms of an HIV infection. NAT is very accurate during the early stages of infection, but if negative, an antigen/antibody test should be done to confirm the results. Healthcare professionals are encouraged to discuss pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which involves taking HIV medications daily to prevent HIV infection for high-risk individuals. For individuals taking PrEP or post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), the accuracy of NAT may be reduced if the patient is HIV-positive (CDC, 2019f).

False-negative testing can occur if the patient is tested during the window period. The window period is the time following infection that extends until a substance is produced in enough quantity to be identified by a particular laboratory test. Nurses can refer to Table 2 below to determine the window period for specific test types. Due to limits of testing during the window period, patients with known exposure or symptoms who have initial negative test results should be encouraged to retest in 45 to 90 days (CDC, 2019f).

Following the initial diagnosis of HIV, the patient will require an HIV-1 RNA quantification to determine the viral load, antiretroviral resistance assay to assess for medication sensitivity, and CD4+ count determination to assist with staging. These will be used by the healthcare team in determining a treatment plan for the patient (CDC, 2019f).

Summary of Laboratory Tests

The following table summarizes information on laboratory testing related to the initial diagnosis of HIV for patients:

Table 2: HIV Test Information

Type of Test | Function | Expected Finding | Note |

Antibody tests | Detects the production of antibodies against HIV. Usually accurate 23 to 90 days from exposure. | Negative | Positive finding means HIV is present in the body. Most home/rapid tests are antibody tests. |

Antigen/antibody tests | Detects the production of antibodies against HIV. Also detects the presence of the p24 antigen, which is a precursor to antibody production. Usually accurate 18 to 45 days from exposure (venipuncture) or 18 to 90 days (capillary blood sampling). | Negative | Allows for earlier, accurate diagnosis since antigens are detectable before antibodies. Used in most laboratory screening for HIV. There is one rapid test available. |

CD4+ count (or T-cell count) | Provides a snapshot of how well the immune system is functioning. Used to confirm the staging/progression of HIV infection. | 500 to 1500 cells/mm3 | Findings decrease as HIV progresses. A result below 200 cells/mm3 indicates AIDS. |

HIV RNA quantification (HIV viral load test) | Measures the amount of HIV present in the blood. Performed at HIV diagnosis and for periodic monitoring. Used with the CD4+ count to determine treatment. | Undetectable | Treatment recommended for levels above 5000 copies/mL; continue until finding is below 500 copies/mL. The goal is to lower the viral load to an undetectable level. This does not mean HIV is not present, just in low concentration. |

Nucleic acid tests (NAT) | Looks for the presence of the virus. Usually accurate 10 to 33 days from exposure. | Negative Some tests show the amount of virus (viral load testing). | Due to the expense, the test is reserved for specific situations (high-risk exposure with symptoms, unclear initial tests). |

Resistance testing (HIV genotype or HIV tropism) | Determines whether the virus is resistant to an HIV medication. Useful when CD4+ counts fall despite therapy. | Sensitive to ARVs. | A patient can be infected with a drug-resistant strain of HIV, or a strain that develops resistance over time due to genetic mutations. |

(CDC, 2019f)

The patient might require additional testing to monitor other aspects of health, including complete blood count (CBC), metabolic profiles (CMP, BMP), lipid profiles, and kidney and liver function tests. These tests can assist in monitoring the effects of medications on the body or in detecting the presence of opportunistic infections or complications. Tests to detect secondary conditions can include tuberculin (TB) skin testing; culture of urine, stool, sputum or drainage to identify infectious agents; and screening for viral hepatitis and other STIs. Secondary or opportunistic conditions can worsen the outcome of HIV infection. Diagnostic imaging such as MRI and CT scans can help determine changes in the brain or lungs such as HIV/AIDS-related dementia, pneumonia, or neoplasm (CDC, 2019f).

Counseling and Prevention

Counseling is required before testing as well as results-counseling afterwards.

Pre-test counseling should include:

- Discussing behavioral risks and goal setting for change to reduce the risk of HIV infection;

- Provide or refer to appropriate prevention, support, and medical services;

- Before having sex with a new partner, it is recommended to have a conversation about former drug use and sexual history. Each person should share their HIV status and consider getting tested if unsure of the results

- Gay and bisexual men should be encouraged to have HIV testing at least annually and more often if the questions under "Testing" are positive (CDC, 2019e; Washington State Legislature, n.d.a).

Post-test counseling should include:

- Negative tests should be followed with a review of the results;

- Goal setting that reinforces pre-test counseling, including behavior change goals, strategies to accomplish the goals, and skills-building to support the goals;

- Appropriate referrals for future care;

- Positive tests should consist of referrals to providers for future care;

- If anonymously tested, discuss that HIV is a reportable condition;

- Either provide partner notification support or referral to public health services for this task;

- Appropriate referrals for alcohol, drug, or mental health counseling, TB screening, and HIV prevention or support services in the local community (CDC, 2019e; Washington State Legislature, n.d.a).

For those who are HIV-positive, ART can effectively maintain health for years. HIV medications also help prevent transmission to others (CDC, 2019e). For patients that are HIV-negative, there are many ways to prevent future HIV infection. Specifically, the nurse should instruct the individual to:

- Use a condom the right way every time they have sex.

- Avoid multiple sexual partners. The risk of infection increases with the number of partners an individual has.

- PrEP should be considered for all individuals who are not in a mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who recently tested HIV-negative, AND anyone, gay, straight, or otherwise who has sex regularly without a condom or who has been diagnosed with an STI in the last six months (CDC, 2019e).

To be eligible for PrEP, individuals must be HIV-negative with no active signs or symptoms of infection. The nurse should also confirm normal renal function and previous hepatitis B (HBV) vaccination status is well-documented prior to starting PrEP (CDC, 2019e).

Individuals who are HIV-negative or are unaware of their status but were recently potentially exposed to HIV during sex (for example, if the condom breaks) can discuss taking PEP with any healthcare provider or emergency room physician within three days of the exposure. The sooner the individual starts PEP, the higher the likelihood of success. Once prescribed PEP, the patient should be instructed to take the medication once or twice daily for 28 days. The chance of getting HIV decreases if the HIV-positive partner is on ART. Patients taking ART can have an undetectable viral load and stay healthy for decades with little to no risk of transmitting the infection to partners (CDC, 2019e).

Condoms can be very effective in preventing HIV and other STIs that are spread through bodily fluids. They are not protective against skin-to-skin STIs such as chlamydia, human papillomavirus (HPV), or syphilis. Male condoms are made of various materials, but latex provides the best protection from HIV. For the person with a latex allergy, a polyurethane or polyisoprene condom is a good option. Natural membrane condoms such as lambskin are not effective against HIV and other STIs as they have small holes allowing microbes to leak through. In addition to the condom, water-based lubricants should be used to lower the risk of breakage or slippage of the condom during sex. Oil-based lubricants should not be used as they weaken the integrity of the condom and may cause it to break. Lubricants containing nonoxynol-9 may irritate the lining of the vagina or anus and increase the risk of HIV infection (CDC, 2019e).

Female condoms provide similar protection to male condoms but are instead placed in the vagina before intercourse. These condoms are made from synthetic latex called nitrile and are safe for those with an allergy to natural rubber latex, and any lubricant can be used with these condoms without concern. They can be effective at preventing pregnancy, HIV, and other STIs. The use of female condoms for protection during anal sex is unknown, but HIV cannot travel through the nitrile barrier (CDC, 2019e).

There is a decrease in the risk of infection for men with HIV-positive female partners if they are circumcised versus uncircumcised. There is no evidence of a decreased risk to women when having sex with uncircumcised males who are HIV-positive. The benefits of circumcision among gay and bisexual men has not been determined at this time (CDC, 2019e).

An HIV diagnosis is life-changing for the patient and their loved ones. Depression, hopelessness, and anger are typical emotional responses, and the healthcare team should provide support through the early stages of disease diagnosis and treatment. An HIV support group can be a great way for patients to share feelings and help work through the challenges, so patients should be referred accordingly. Seeing how others have managed their diagnosis and live with the disease can be a source of empowerment and encouragement for patients. Nurses should remind the patient that having HIV does not mean they have AIDS, and they may never progress to the worst aspect of the illness spectrum (CDC, 2019f).

Transmission and Infection Control Guidelines

Viral Load

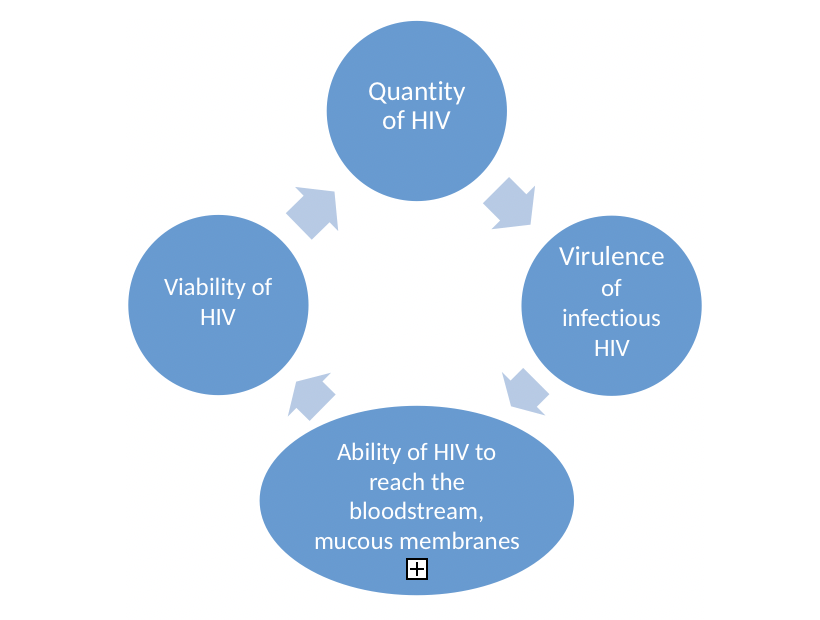

The viral load is essential to the transmission of the virus. For transmission to occur, there must be enough of the virus, referred to as sufficient dose. The term viral load refers to the amount of HIV in an individual sample of blood. When the viral load is high, it indicates that the immune system is not fighting the virus well. Further, the higher viral load means that the person is more infectious to others. A low viral load is associated with a low rate of infection to sexual contacts while a high viral load is associated with higher infection risk (NIH, 2018). A concept recognized by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in January 2019 is that an undetectable amount of HIV correlates with untransmittable HIV. This concept is called "U=U". There is currently a campaign to recognize that compliance with ART can lead to an undetectable viral load, leading to the patient being unable to transmit the disease to others. The U=U campaign encourages medication compliance, which suppresses the viral load to undetectable levels to avoid exposing sexual partners to the infection (NIH, 2019). Figure 2 depicts the factors affecting the transmission of HIV.

Figure 2: Factors Affecting Disease Transmission

(NIH, 2018)

Modes of Transmission and Risk Factors

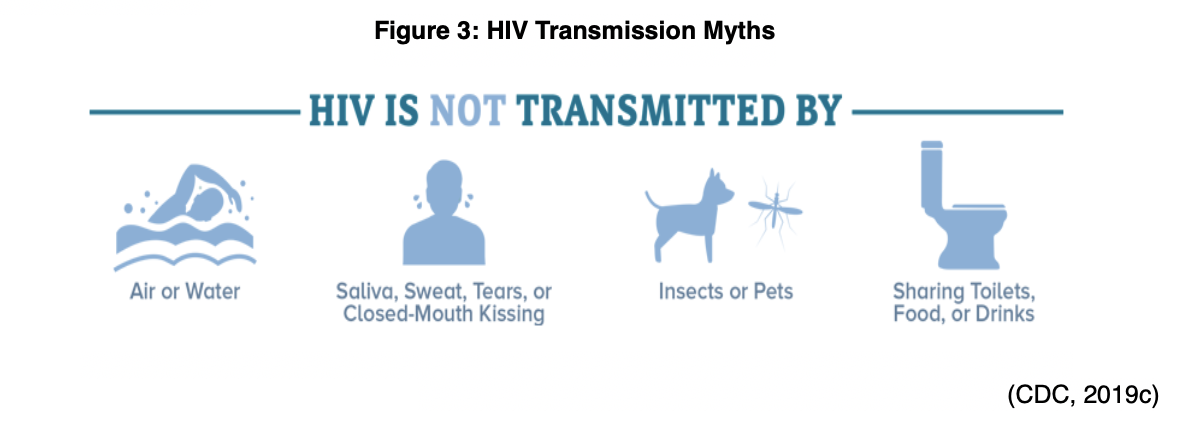

AIDS can only be acquired from infection with HIV. The virus must enter the individual's bloodstream and is not passed casually from person-to-person. See Figure 3 (below) for common HIV transmission myths.

For a person to become infected with HIV, the following conditions must be present: 1) and HIV source, 2) a sufficient amount of virus, and 3) access to another person's bloodstream (CDC, 2019c).

Without these conditions, HIV cannot spread. HIV is transmitted through blood and body fluids, such as semen, saliva, vaginal secretions, and breastmilk. In the US, HIV is mainly spread by unprotected anal or vaginal sex with someone who is infected with HIV without taking medications to prevent HIV. For an HIV-negative partner, receptive anal sex is the highest-risk sexual behavior, but it can also be acquired from penetrative anal sex. Either partner can acquire HIV through vaginal sex, though it is less risky than anal sex. The CDC reports that all forms of oral sex have a very low risk of transmitting HIV, but it is theoretically possible if an HIV-positive man ejaculates in his partner's mouth during oral sex. Sharing needles or syringes with someone who is HIV-positive is also high risk. Even the rinse water or other equipment used to prepare drugs for injection can lead to HIV infection. HIV can live in a used needle for up to 42 days, depending on the conditions of storage (CDC, 2019c).

While performing patient care, nurses are often exposed to bodily fluids and therefore need to be aware of the pathophysiology of the virus, the impact that it has on health care, and protective precautions that need to be employed. While HIV is found in feces, urine, tears, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, cervical cells, lymph nodes, corneal tissue, and brain tissue, these are not the most common methods of transmission. Because HIV cannot live long outside the human body, the risk of transmission is decreased for healthcare workers. Despite this, careful precautions to protect those caring for individuals with HIV/AIDS will be discussed in a later section (CDC, 2019c).

As previously mentioned, HIV cannot survive long outside the human body and cannot reproduce outside a human host. For these reasons, HIV cannot be spread by vectors such as mosquitos, ticks, or other insects. Handling food, saliva exposure, or being scratched by an HIV-positive person cannot cause HIV infection. Tattoo or body piercing equipment can cause an HIV infection, but the risk is very low and would be due to unsanitary practices such as sharing needles (CDC, 2019c).

Of interest to note, an unusual skincare practice called vampire facials may have exposed patients to HIV infection in a New Mexico spa in 2019. The use of a procedure called platelet rich plasma (PRP) draws blood from the person and spins it down using a centrifuge to extract platelet-rich plasma. The patient then undergoes extensive microdermabrasion, and the platelet mixture is smeared over the raw skin like a mask. The process stimulates new skin and collagen production. In the New Mexico case, poor infection control technique with the blood acquisition and preparation exposed patients to HIV from another infected patient (WebMD, 2019).

Other factors that can affect transmission include other STIs, substance abuse, and relationship equality issues. There are also unusual cases of transmission including bites and workplace exposure (CDC, 2019c). Let's look at each of these a little closer.

STI's increase the risk of infection with HIV due to skin and mucous membrane compromise that allows HIV easier access to the body. Symptomatic herpes and syphilis can cause a break in skin integrity from blisters and sores. Chlamydia causes inflammation, which can increase HIV viral shedding and the viral load in genital secretions. Any genital ulcers, wounds, or inflamed tissues can become an easy entry point for HIV and thus increase the risk of exposure (CDC, 2019c).

Substance abuse increases the risk of HIV exposure in several ways. In addition to the injectable drugs that cause exposure through shared needles, the use of alcohol and non-injectable drugs also increase risk. A person is more likely to participate in risky behavior and have impaired judgment, leading to increased risk of infection. Also, substances can alter the pain response and lead to unnoticed sores or open wounds in the mouth or genital area, which increases the risk of HIV infection as well as other STIs (CDC, 2019c).

Domestic violence and cultural implications can create an environment that puts one of the partners in a relationship at risk. For instance, in some cultures, women are not allowed to question their partner and expected to live under rules and restrictions related to sexual activity. They may not be able to ask for protection, which places them at increased risk of infection. Women and men who are victims of domestic abuse and sexual abuse may be unable to discuss sexual history or safe sex practices. This problem can exist in all types of relationships, including heterosexual, bisexual, gay, and transgender. Other inequality issues that could lead to HIV transmission include substantial differences in age or wealth. Any situation in which one partner has power or control over another, the likelihood of protection and safe sex practices goes down and the possibility of exposure to HIV or other STIs increases (CDC, 2019c).

Human bites should not cause the transmission of HIV, however, if someone has bleeding gums or open sores in their mouth there is a small risk of exposure. Other diseases can be transmitted via a human bite and care should be taken to cleanse the bite wound immediately with soap and water, followed by antibiotic ointment as soon as possible (CDC, 2019c).

Workplace exposure should be considered where potentially infectious materials exist, including blood or bodily fluids. Appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) is required to avoid any potential exposure. Infection control practices will be discussed next (CDC, 2019c).

Infection Control Practices/Personal Protection in the Workplace

Each healthcare organization should have a blood borne pathogen policy and procedure that protects employees from exposure to blood and potentially infectious bodily fluids. Healthcare workers are at higher risk of exposure to blood and bodily fluids during the delivery of routine patient care. In addition to healthcare workers, first responders, law enforcement, and public service employees are at risk of blood borne pathogens such as HBV, Hepatitis C (HCV), and HIV in their work roles. Each employer is responsible for training their employees regarding the risk of exposure to blood borne pathogens and provide the equipment to protect them from exposure, including PPE. Exposure types include occupational exposure and exposure incidents (CDC, 2014).

Occupational exposure is exposure of the skin, eyes, mucous membrane, or a parenteral to blood or other potentially infectious material (OPIM) that results from an employee's routine duties. An exposure incident is a specific eye, mouth, mucous membrane, non-intact skin, or parenteral contact with blood or OPIM that is the result of an employee's duties. Non-intact skin would include acne, cuts, abrasions, dermatitis, or hangnails (CDC, 2014).

While this module focuses on HIV, the risk of HBV, HCV, or other pathogens is of equal concern to healthcare workers. Other infectious diseases that could be present in blood or OPIM include Hepatitis D, malaria, leptospirosis, viral hemorrhagic fever, syphilis, babesiosis, brucellosis, arboviral infections, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and adult T-cell leukemia//lymphoma caused by HTLV-1. Incidentally, HBC is the most common blood borne pathogen in the US, and the primary transmission route is through blood exposure (CDC, 2014). OPIM includes semen, vaginal secretions, cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid, synovial fluid, pericardial fluid, amniotic fluid, peritoneal fluid, or saliva. Body fluids that are NOT considered infectious for HIV include urine, feces, or vomit unless there is visible blood noted (CDC, 2014).

The CDC notes that a 0.3% risk exists after percutaneous exposure to HIV and 0.09% after a mucous membrane exposure, yet any chance is too much for an individual healthcare worker. Primary prevention for occupationally acquired HIV infection is the most important strategy. Standard precautions with PPE should be meticulously followed to avoid exposure (Kuhar et al., 2018).

Infection control includes two tiers of recommended precautions to decrease the risk of exposure to workers and the spread of infections within the healthcare system. The first tier consists of standard precautions which should be maintained for ALL patients. The second is transmission-based precautions that are used with certain known or suspected infections (CDC, 2016). Standard precautions include:

- Perform hand hygiene before and after any patient care;

- Access to and consistent use of appropriate work practices such as not recapping needles;

- Work practice controls regarding the handling of infectious materials such as dressings;

- Use PPE when there is a risk of possible exposure to infectious materials;

- Properly handle and clean/disinfect all patient care equipment, instruments, or devices;

- Handle linens and laundry carefully to avoid exposure;

- Follow safe injection practices;

- Wear a surgical mask when performing lumbar punctures; ensure the safe handling of sharps and needles (CDC, 2016).

In addition to the standard precautions above, 2019 Guidelines for Preventing the Transmission of Infectious Agents identifies transmission-based precautions as contact, droplet and airborne precautions. HIV is primarily managed through standard precautions and does not qualify by itself for the utilization of any transmission-based precautions. However, HIV/AIDS patients may have other infections requiring additional precautions such as respiratory, gastrointestinal, or other opportunistic infections (Siegel, Rhinehart, Jackson, & Chiarello, 2019).

PPE should be used with all aspects of standard precautions and transmission-based precautions. Any time the worker is potentially exposed to blood or OPIM, they should incorporate PPE. Examples are gloves, gowns, masks, protective eyewear, and chin-length plastic face shields. Latex gloves should be worn when drawing blood, starting IVs, and any other procedures with potential for blood/OPIM exposure. Employers must provide non-latex alternative products for employees with a latex allergy or sensitivity. Nitrile, vinyl or other materials may be substituted for the latex gloves. PPE should be clean and should be single-use or properly laundered and decontaminated by the employer after each use. Protective gowns should be worn over lab coats or scrubs when contamination is likely. These should be immediately discarded as soon as the procedure is completed and not worn outside the patient room. Patient rooms should be cleaned following the Environmental Protection Agencies (EPA) standards for cleaning environmental surfaces using an approved antimicrobial agent such as bleach (CDC, 2016).

Safer medical devices should be used by all healthcare organizations to decrease or eliminate employee exposure. The devices should be identified and examined for safety and reviewed by staff for appropriateness based on their population before use. Documentation of this screening and implementation of devices should be maintained in the ECP, as previously mentioned (Siegel et al., 2019).

Home environment precautions should include:

- For household items contaminated with body secretions, clean the area with soap and water, then disinfect the surface;

- Store clothes or linens soiled with excreta in plastic until able to launder. Rinse, discarding the water in the toilet. Wash the fabrics in hot water, adding 1 cup of bleach;

- Keep the home environment clean by using a disinfectant such as chlorine bleach;

- Wash dishes in hot soapy water or use a dishwasher, if available.

- Do not handle pet urine or feces; avoid cleaning birdcages, litter boxes, or aquariums;

- Discard solid waste or cleaning solutions in the toilet;

- Discard contaminated, disposable items in a plastic bag (paper towels, dressings, and perineal pads). Tie the bag securely, and dispose = with regular household garbage;

- Designate a sharps container for disposal of needles to prevent stick injuries. Use a metal coffee can or hard plastic bleach bottle. Once full, add bleach, seal with tape, and place in a plastic bag in the regular trash (CDC, 2016).

Clinical Manifestations of HIV/AIDS

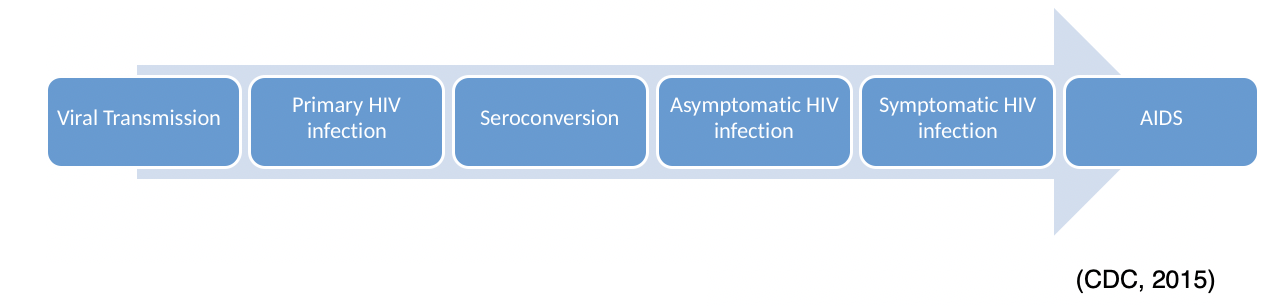

The natural progression of HIV follows a deteriorating clinical course (see Figure 4 below). Typically, the disease unfolds in the following manner:

Figure 4: The Clinical Course of HIV Infection

During viral transmission, the individual has come in contact with the virus. Initially, he or she will have no symptoms but can be infectious within five days (CDC, 2015).

Primary HIV infection occurs within the first few weeks. A high viral load during this phase indicates that infected individuals are more likely to pass the disease to others, and yet they may be unaware of their HIV status. Initial HIV symptoms during this period include fever, lymphadenopathy (swollen glands in the neck, armpits, or groin) rash, fatigue, and sore throat known as seroconversion syndrome. The person may think they have the flu or another viral illness unless they have a reason to suspect HIV. An inaccurate diagnosis could occur during this time as these symptoms subside in days to weeks (CDC, 2015).

Seroconversion occurs between the time of initial exposure and the time that antibodies can be detected on an HIV test. Seroconversion can vary but typically occurs between nine days and six months after exposure (CDC, 2015). Asymptomatic HIV is a term used to describe patients with positive results on their HIV test(s) but no clinical symptoms. This period may last up to ten years with no outward appearance of illness. Without verification of testing, the individual may be unaware they are infected. There are no specific HIV symptoms; however, HIV affects the normal functioning of the immune system, the kind and number of blood cells, the body's basic metabolism, structure and function of the brain and the amount of fat and muscle distribution of the body. Symptoms commonly seen include:

- Persistent low-grade fever;

- Pronounced weight loss without dieting;

- Persistent headaches;

- Difficulty recovering from colds or viruses;

- Diarrhea lasting over a month;

- Illnesses that are more severe than they would typically be;

- Loss of muscle tissue and body weight;

- Thrush (yeast infection which occurs in the mouth);

- Vision or hearing loss;

- Nausea or vomiting;

- Confusion or dementia;

- Fatigue;

- Urinary or fecal incontinence;

- Chronic pneumonia, sinusitis or bronchitis (CDC, 2015)

HIV in women can lead to several gynecological problems including pelvic inflammatory disease, abscesses of the fallopian tubes and ovaries, and recurrent yeast infections. In women with HPV, they are at an increased risk of cervical dysplasia and cervical cancer when co-infected with HIV. Invasive cervical cancer is also an AIDS-defining condition. Routine screening for cervical cancer is recommended for nearly all women, but it is crucial for HIV-positive women. Women in the US receive fewer healthcare services than men and may not be diagnosed with HIV until later in the disease process. This problem can make the disease harder to control in this group of patients (CDC, 2015).

The progression to AIDS has been dramatically slowed in the US through ART, yet there are less developed countries where the progression can be remarkably rapid (CDC, 2015). While ART has been shown to slow or temporarily halt the progress of the disease, there are specific co-factors that exacerbate the progress of AIDS. These include:

- Smoking;

- Advanced age;

- Drug use;

- Poor nutrition;

- Co-infection with HCV or any other STI (CDC, 2015).

The average time lapse from HIV infection to AIDS is eight to ten years in untreated patients. Once diagnosed with AIDS, the prognosis varies based on medication compliance and healthy living habits (CDC, 2015).

Access to medical care is crucial in determining the outcomes for patients who have HIV/AIDS. The medications to treat HIV infections are numerous and complex, and the care of patients diagnosed with HIV is now a medical specialty. Where possible, patients should seek a healthcare provider that is skilled in the treatment of HIV/AIDS. Often, a person with HIV/AIDS can get help by accessing an HIV healthcare provider through the assistance of case managers in the community. AIDS service organizations are also available in many communities. Many organizations offer a medical case manager that will assess the individual's needs and support systems available, then assist with obtaining the needed services to provide optimal patient outcomes (WSDH, n.d.c).

Treatment

In addition to the previously discussed prevention and risk reduction techniques for individual patients, efforts to develop a vaccine to prevent HIV or minimize its effects are underway. Although no vaccine is currently available to the public, the nurse should be aware that patients who have received an HIV vaccine as part of a clinical trial might test positive for HIV antibodies. As previously mentioned, some patients at high-risk might take ARVs known as PrEP, but the effectiveness depends on the ability of the patient to adhere strictly to the daily prescribed regime (Avert, 2019).

Additionally, patients might be able to take PEP to prevent infection following actual or suspected exposure. PEP must be initiated within 72 hours of the exposure event. Emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil (Truvada) is FDA-approved for both PrEP and PEP. Detailed information about specific treatment guidelines is available at the NIH’s website.

Medication

According to the WHO, AIDS-related deaths fell by 37% between 2000 and 2018, due to international efforts with ART and education. In 2018, there were 23 million reported people living with HIV and receiving ART therapy globally (WHO, 2019). For individuals who test positive, starting treatment immediately is vital for control of the disease. The CDC (2019f) recommends that all HIV-positive individuals begin ART upon diagnosis regardless of their health status or duration of HIV infection. HIV is not curable. However, medications for HIV management help to slow virus replication and therefore reduce the viral load.

ART reduces HIV-related morbidity and mortality throughout the disease as well as decreasing and suppressing the viral load, maintaining elevated CD4+ cell counts, delaying the progression to AIDS, improving survival rates, and reducing the risk of exposure to others. ART should begin immediately upon diagnosis. The nurse should be sure to provide the patent with accurate education on ART therapy benefits and risks, as well as the importance of strict and consistent adherence to therapy (CDC, 2019g).

The goals of treatment with ART include providing a long life, a high quality of life, promoting optimal immune function, and minimizing the HIV viral load to lower the risk of transmission to others. Specific medications work at various stages of HIV replication; therefore, most patients take more than one drug, or an HIV regime. An HIV regime is a combination of three or four HIV medicines that is taken daily. Taking a combination helps to prevent medication resistance, reduce adverse effects, and decrease the dosage required of each component medication (NIH, 2018).

The most recent recommendations from the NIH (2018) for ART initiation is:

"An antiretroviral (ARV) regimen for a treatment-naïve patient generally consists of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) administered in combination with a third active ARV drug from one of three drug classes: an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI), a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), or a protease inhibitor (PI) with a pharmacokinetic (PK) enhancer (also known as a booster; the two drugs used for this purpose are cobicistat (Tybost) and ritonavir (Norvir)(NIH, 2018, p.3).

The term "treatment naïve" refers to a person who has never undergone treatment for a particular illness (NIH, 2018). Table 3(below) outlines the different ARV categories, examples, and implications.

Table 3: Antiretroviral Medications

Type of Medication | Example | Adverse Reactions (AR) | Nursing Notes |

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs)- Inhibits reverse transcriptase and incorporates into viral DNA, resulting in DNA chain termination |

| Possible AR

Severe AR

|

|

Non-Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) - Bind non-competitively to HIV-1's reverse transcriptase and prevents viral RNA conversion to DNA. |

| Possible AR

Severe AR

|

|

Protease inhibitors (PIs) - inhibit the protease enzyme needed for the virus to replicate. |

| Possible AR

Severe AR

|

|

Fusion Inhibitors – blocks the fusion of HIV with the host cell. | enfuvirtide(Fuzeon) | Possible AR

Serious AR

|

|

CCR5 Antagonists – block the CCR5 receptor on CD4+ T-cells to prevent the entry of HIV into the cell. | maraviroc(Selzentry) | Possible AR

Serious AR

|

|

Integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) – block the enzyme integrase, which in turn keeps HIV from inserting its DNA into the host DNA. | raltegravir(Isentress) dolutegravir(Tivicay) | Possible AR

Serious AR

|

|

Post attachment inhibitors- block CD4+ receptors on the surface of specific immune cells that HIV needs to enter the cells. | ibalizumab-uiyk(Trogarzo) | Possible AR

Serious AR

|

|

PK enhancers increase the effectiveness of other HIV medicine included in a regime. | cobicistat (Tyboost) | Possible AR

|

|

(USDHHS, 2019)

Combination products are also available that contain more than one of the ARV medications. Additionally, the patient might require drugs to treat secondary or opportunistic conditions, such as antineoplastic medications, antivirals, or antifungals, or to combat adverse effects, such as antidiarrheal medications. If the patient has depression, antidepressants such as imipramine (Tofranil) and fluoxetine (Prozac) might be prescribed. These have secondary beneficial effects such as reducing fatigue and lethargy. Methylphenidate (Ritalin) can improve neuropsychiatric impairment (NIH, 2018).

ART adherence and viral suppression drives the successful outcomes of ART therapy. Proper administration of the medication regime leads to viral suppression, and undetectable levels of the virus are possible. As previously mentioned, the concepts of U=U have been recognized as scientifically sound among the majority of experts. The NIH's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) reviewed the extensive amount of scientific evidence behind U=U leading to widespread acceptance of the concept (NIH, 2019). The validation of HIV treatment as a prevention strategy adds additional rationale for compliance with ART among HIV-positive patients and further decreases the stigma that patients live with daily. For the virus to remain undetectable, strict compliance with ART is required (CDC, 2019g).

In the few months following initiation of ART, some patients may develop immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) as a result of the sudden boost in the body's immune capabilities. IRIS results in an exaggeration of symptoms associated with opportunistic pathogens that might be present in the patient's body (tuberculosis, fungi, hepatitis, and cytomegalovirus). Treatment with corticosteroids may be required to reduce the inflammation and resolve this condition (NIH, 2018).

Treatment with HIV medications can cost well over $1000 per month. Private and government insurance programs offer coverage for HIV medical visits and HIV medications. In some cases, the co-pays are very high and may cause the patient financial hardship (WSDH, n.d.a). Health insurance is required to pay for many of the medications used to treat HIV. For the patient who does not have health insurance, assistance can be applied for through government programs including Medicaid, Medicare, the Ryan White AIDS Program, or other resources such as the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) (CDC, 2019f).

Nursing Actions with Medications

- Review laboratory findings to monitor for adverse medication effects (e.g., alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, bilirubin, mean corpuscular volume, high-density lipoproteins, total cholesterol, and triglycerides);

- Monitor total CD4+ T-lymphocyte count, CD4 percentage, and the ratio of CD4 to CD8 cells to monitor disease progression and effectiveness of the medication regimen;

- Reinforce teaching to the patient about the potential adverse effects of the medications and explore ways to decrease the severity of adverse effects. This promotes adherence to the prescribed treatment regime;

- Obtain a list of prescribed, over-the-counter, or herbal medications the patient takes to monitor for possible interactions (NIH, 2018).

Patient Education for Medication Issues

As a patient advocate, the nurse should encourage the patient to:

- Take medications on a regular schedule and do not miss doses. Missed medication doses can cause medication resistance. The goal is on-time dosing 90% of the time to maintain effectiveness;

- Obtain information from the provider regarding protocols for missed doses specific to the patient’s medications;

- Understand medication administration timing and restrictions, and potential interactions with food or other substances (NIH, 2018).

Acute Nursing Care/ Nursing Interventions for HIV

Nursing care in an acute setting for a patient who has HIV should be prioritized according to need. Each body system is affected by either the pathophysiology of HIV or secondary/opportunistic conditions. The patient's respiratory status might be affected due to fatigue or secondary infection. Confusion is possible if the brain has been affected. Pain is often a problem, so the nurse should implement both pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures to promote comfort. Changes to the endocrine system can affect nutrition, gonads, and hormone production. Nutrition is another area of concern for a patient who has HIV. The nurse should intervene to ensure the patient maintains or gains weight, drinks adequate fluid, and demonstrates laboratory evidence of proper nutrition and electrolyte stability. Diarrhea is a common problem; the nurse should promote regular, solid bowel movements and prevent complications from fluid or electrolyte imbalances. Skin integrity can be compromised easily, so skincare and prevention of breakdown are essential nursing strategies (Hinkle & Cheever, 2014). Specifically, the nurse should:

- If the patient is immunocompromised provide a private room if possible and keep fresh plants, fruits, and vegetables out of the patient’s room;

- Provide two to three liters of fluid input daily;

- Monitor fluid intake/urinary output as well as nutritional intake;

- Obtain daily weights to monitor weight loss;

- Monitor electrolytes;

- Monitor skin integrity for rashes, open areas or bruising;

- Monitor pain status and implement interventions to promote comfort;

- Monitor vital signs (especially temperature as an indicator of infection);

- Auscultate lung sounds and check respiratory rate;

- Check neurological status to monitor for confusion, dementia, or visual changes;

- Monitor bowel sounds and administer antidiarrheal medications as indicated;

- Encourage activity alternated with rest periods;

- Administer supplemental oxygen as needed;

- Reinforce patient teaching;

- Assist the patient in identifying primary support systems;

- Employ the principles of asepsis when performing venipunctures or other invasive procedures;

- Maintain strict adherence to standard precautions (Hinkle & Cheever, 2014).

The nurse should demonstrate sensitivity in addressing psychological issues with the patient. Using therapeutic communication techniques, the nurse can encourage the patient to express concerns and identify positive self-characteristics. Other strategies include the following:

- Promote patient independence and self-care;

- Advocate for patient decision-making;

- Assist the patient in setting goals;

- Determine a baseline for the patient’s typical social patterns and monitor for changes (Hinkle & Cheever, 2014).

Interprofessional Care

Because HIV changes the course of the patient's life, the patient faces many challenges in learning to manage the disease and maintain his or her preferred lifestyle. This chronic condition affects the entire body as well as impacting the patient financially and psychologically. The patient can require recurrent hospitalizations when immune function wanes, and illness occurs. The nurse should assist with care coordination by connecting the patient with members of the interprofessional team that can help with various needs related to HIV diagnosis and disease progression:

- Infectious disease services can manage ART;

- Respiratory services can improve the respiratory status and provide portable oxygen;

- Nutritional consults are needed for dietary supplementation following recommendations from a registered dietician;

- Rehabilitation services can be consulted for strengthening and improving the patient’s level of energy;

- Support groups for HIV/AIDS patients, family members, and support persons can assist with psychological coping and grieving related to the condition;

- Home health services are indicated for patients who need help with strengthening and assistance regarding activities of daily living (ADLs). Food services are indicated for patients who are homebound and need meals prepared. Home health services can also provide support with IVs, dressing changes, and total parenteral nutrition (TPN);

- Long-term care facilities can be indicated for patients who have end stage AIDS;

- Hospice services are usually indicated for patients who have stage 3 HIV;

- Respite care can assist loved ones with the care of a patient who needs significant assistance for ADLs;

- Community programs might be able to provide patient assistance with housekeeping, shopping, and transportation;

- A social worker can assist the patient with financial support resources;

- A case manager can coordinate services for the patient across the continuum of care (Hinkle & Cheever, 2014).

Patient Self-Management

The nurse plays an essential role in assisting the patient with self-management by discussing topics related to the prevention of transmission of HIV to others and protecting the patient from acquiring opportunistic infections. Education should be targeted around prolonging a functional life and prevention of complications. Patients may or may not be aware of the potential risk of transmission from blood. Therefore, protecting close contacts from exposure to contaminated blood or other body secretions is essential. Another vital role for the nurse concerning health promotion and disease prevention relates to ensuring the patient is up to date with immunizations. The timing of vaccines is crucial; they should be administered before exposure to opportunistic infections that will develop in the third stage of the disease process. Most patients should obtain the seasonal influenza vaccine and the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Some immunizations may be appropriate, even with a CD4+ count below 200 cells/mm3. Older adult patients may be at increased risk for complications due to age-related changes and conditions, such as decreased resistance to infection, fluid and electrolyte imbalances, malnutrition, skin alterations, and loss of muscle tissue. Also, the nurse needs to emphasize for the patient to take medications on a regular schedule, and not to miss any doses. Missed medicines can cause medication resistance (Hinkle & Cheever, 2014). Self-care education for the HIV/AID patient should also include:

- Report manifestations of infection immediately to the provider (cough with or without sputum, shortness of breath, pain in the mouth or with swallowing, swollen lymph nodes, gastrointestinal upset, difficulty urinating, mental changes, edema or drainage);

- Practice good hygiene, including frequent hand hygiene;

- Bathe daily using an antimicrobial soap. If a full bath isn’t possible, at least clean the armpits, genitals, groin, and anus;

- Avoid raw foods (fruits, vegetables, paprika, black pepper) and undercooked foods (meat, fish, eggs);

- Do not drink liquids that have been sitting for over 1 hour, and rewash cups before use;

- Sanitize your toothbrush weekly in the dishwasher, or by pouring bleach solution over it and rinsing with hot, running water;

- Avoid crowds, and do not travel to countries with poor sanitation;

- Identify positive coping mechanisms and seek support to manage feelings of grief or loss;

- Return to the provider as scheduled for monitoring of CD4+ levels and percentages, and viral load. Routine lab work is an integral part of ensuring medications are working and preventing secondary conditions;

- Talk to your healthcare team about helping to manage adverse medication effects. Do not begin any new prescription, over-the-counter, or botanical supplements without discussing it with the provider who manages your ART therapy;

- Maintain a well-balanced diet; monitor for and report any significant weight loss;

- Avoid sharing items that contain body secretions or blood, such as eating utensils, razors, or toothbrushes;

- Avoid exposure to individuals who have colds or flu viruses (Hinkle & Cheever, 2014).

Caring for a Patient who has AIDS

In general, the nurse should implement many of the care strategies previously mentioned for a patient who has HIV; however, the AIDS patient has a more complicated disease status, so the nurse may need to be more aggressive regarding symptom management and coordinate with a larger team of healthcare professionals to provide comprehensive management of the patient's condition. A patient who is diagnosed with AIDS may be eligible for some government benefits, including housing and disability assistance that is not available with initial HIV diagnosis (Hinkle & Cheever, 2014).

When planning for the care priorities of patients who have AIDS, it is vital to address the potential problems and comfort measures to support these patients. While treating existing conditions, the nurse must also be proactive in preventing the development of a new infection. The major need categories are addressed as life-threatening needs, physical needs, and psychological needs (Hinkle & Cheever, 2014).

Life-Threatening Care Needs

The nurse can use the prioritization principle of airway, breathing, and circulation to address life-threatening patient needs. Some patients experience problems with airway clearance and could develop respiratory distress. If this is anticipated, the nurse should have suction equipment and oxygen available. Rigorous monitoring of vital signs, including breath sounds, is imperative. Bronchodilators and antibiotics should be given as prescribed and the patient should be monitored for the symptoms of secondary infections. Electrolyte disturbances could lead to arrhythmias or alterations in blood pressure, and neurological changes place the patient at increased risk for injury (Hinkle & Cheever, 2014).

Physical Care Needs

Patients who are immunocompromised due to AIDS are susceptible to developing a range of diseases. Therefore, the standard infection control precautions should be reinforced with the patient and family, and everyone who enters or leaves the room should be reminded to wash their hands properly. The patient should be monitored for a range of opportunistic oral infections, as well as meningitis. They should be regularly assessed for hydration, and their weight monitored. Nutritional supplements should be encouraged as required. As the disease process progresses, the patient may experience fatigue and require assistance with their ADLs. They should be encouraged to relax and rest, and they may have to restrict visitations from family and friends until they feel strong enough to engage in these activities. The patients should be regularly assessed for pain and given prescribed medication that will be effective for the patient (Hinkle & Cheever, 2014).

Emotional Care Needs

An HIV diagnosis is life-changing for the patient and their loved ones. Depression, hopelessness, and anger are typical emotional responses, and the healthcare team should provide support through the early stages of disease diagnosis and treatment. An HIV support group can be a great way for patients to share feelings and help work through the challenges, so patients should be referred accordingly. Seeing how others have managed their diagnosis and live with the disease can be a source of empowerment and encouragement for patients. Nurses should remind the patient that having HIV does not mean they have AIDS, and they may never progress to the worst aspect of the illness spectrum (CDC, 2019f).The patient may be embarrassed about their situation and should be encouraged to express their feelings and discuss their problems. The responsibilities and expectations of the patient should be addressed. A discussion on lifestyle choices should be handled in a non-judgmental manner. In addition to using therapeutic communication techniques, the nurse can offer referrals to counselors or spiritual advisors if the patient expresses a desire to talk further (Hinkle & Cheever, 2014).

Alternative Therapies

Patients may choose to use alternative and complementary therapies to supplement prescribed therapies in an attempt to alleviate the manifestations of HIV (NIH, 2018). Common treatments may include the following:

- Supplements such as vitamin D to promote bone health;

- Herbal products such as Echinacea and ginseng for their effects on improving immunity;

- Shark cartilage used in the treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma;

- Physical therapy, occupational therapy, yoga, massage, and acupuncture;

- Relaxation techniques to alleviate stress and fatigue, such as meditation, visualization, guided imagery, and hypnosis;

- Selenium supplements to slow the progression of HIV (NIH, 2018).