About this course:

The purpose of this course is to outline and review for nurses the evidence-based process for identifying and intervening in cases of human trafficking, as most healthcare providers are unfamiliar with how to care for or report trafficking victims (Greenbaum et al., 2017; Powell et al., 2017). This will also serve to satisfy the specific nursing professional development requirements for this topic in the states of Florida (per statutes section 787.062), Michigan (per administrative rule 338.10105), and Texas (per House Bill [HB] 2059, 86th Session, 2019; Texas Occupation Code, 2019).

Course preview

Texas Health and Human Services Approval Letter

The purpose of this course is to outline and review for nurses the evidence-based process for identifying and intervening in cases of human trafficking, as most healthcare providers are unfamiliar with how to care for or report trafficking victims (Greenbaum et al., 2017; Powell et al., 2017). This will also serve to satisfy the specific nursing professional development requirements for this topic in the states of Florida (per statutes section 787.062), Michigan (per administrative rule 338.10105), and Texas (per House Bill [HB] 2059, 86th Session, 2019; Texas Occupation Code, 2019).

At the conclusion of this activity, the learner will be prepared to:

- define the key concepts and terms related to human trafficking, as well as its current epidemiology, prevalence in the United States, and history

- outline the health impacts, identifiable risk factors, and red-flag indicators of human trafficking to identify potential cases of human trafficking accurately and consistently

- discuss evidence-based and validated screening tools for cases of human trafficking

- review the victim-centered methods of interacting with and providing trauma-informed care to victims and survivors of human trafficking once correctly identified

- delineate the proper referrals, resources, reporting protocols that should be followed, as well as safety planning that the nurse should provide once human trafficking has been identified

A few key terms should first be defined to facilitate a comprehensive discussion regarding human trafficking:

Human trafficking is defined as the use of force, fraud, or coercion to facilitate labor, services, or commercial sex from an individual. It is both a federal crime against an individual and a public health concern in the US. It may be transnational or domestic but does not require the transport of an individual across state or national boundaries (The National Human Trafficking Hotline [NHTH], n.d.-c; Office for Victims of Crime [OVC], n.d.; Office on Trafficking in Persons [OTP], 2017; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020; US Immigration and Customs Enforcement [ICE], 2017). For minors under the age of 18 who are trafficked, the presence of force, fraud, or coercion is not required (Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020, p. 2).

- A commercial sex act is “any sex act on account of which anything of value is given to or received by any person” (NHTH, n.d.-a; OTP, 2017, p. 2; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020, p. 2). If the commercial sex act is between willing and consenting adults; does not include force, fraud, or coercion; and does not affect their human rights, this is considered consensual commercial sex or sex work (NHTH, n.d.-c; StopTheTraffik.org, 2018). An adult who is threatened, forced, or pressured by another individual to engage in commercial sex or afraid to stop engaging in commercial sex due to fear of retribution or violence may be a trafficking victim (NHTH, n.d.-d). These cases can be difficult to distinguish.

- Force includes, but is not limited to, “physical restraint, physical harm, sexual assault, and beatings. Monitoring and confinement are often used to control victims, especially during early stages of victimization to break down the victim’s resistance” (OTP, 2017, p. 2).

- Fraud includes ”false promises regarding employment, wages, working conditions, love, marriage, or a better life” (OTP, 2017, p. 2).

- Coercion includes “threats of serious harm to or physical restraint against any person, psychological manipulation, document confiscation, and shame and fear-inducing threats to share information or pictures with others or report to authorities” (OTP, 2017, p. 2).

The top 5 forms of force/fraud/coercion reported by victims or survivors of sex trafficking in 2019 included induced or exploited substance misuse issues, physical abuse, sexual abuse, intimidation with weapons, and emotional abuse. The top 5 means reported by victims/survivors of labor trafficking consisted of withholding pay, excessive working hours, threats regarding immigration reporting, verbal abuse, and withholding or denying basic needs (NHTH, 2019).

Human smuggling is commonly confused with human trafficking but is defined as a mutual transaction between consenting adults that concludes with arrival at the desired destination via the illegal transport of an individual across a national border. It is usually consensual and must be transnational. Smuggling indebtedness can lead to human trafficking to resolve a fee owed (ICE, 2017; OTP, 2017; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020).

Sex trafficking is defined as the “recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, obtaining, patronizing, or soliciting of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act, in which the commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such as has not attained 18 years of age” (NHTH, n.d.-a; OTP, 2017, p. 1; OVC, n.d., sect 1).

Labor trafficking is defined as the “recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery” (NHTH, n.d.-a; OTP, 2017, p. 1; OVC, n.d., sect 1).

The terms victim or survivor are used throughout this activity to refer to those who are currently or have previously been harmed as a direct result of being trafficked, either for sexual or labor purposes. These terms do not imply how individuals perceive themselves and should not be interpreted as labels. We will also utilize the term healthcare provider (HCP) to refer to the healthcare professional that is directly caring for the patient, whether that be a nurse of any professional level, a physician, or other member of the multidisciplinary healthcare team.

Epidemiology and Statistics

The data collected by the NHTH (2019) are based on an aggregate of information gathered from phone calls, text messages, chats, email messages, and online tip reports. These data are not complete, limited by human trafficking’s illicit and clandestine nature (NHTH, 2019; Stopthetraffik.org, 2018). Furthermore, victims may feel a reluctance to identify themselves (Human Sex Trafficking, 2017). In 2019, the NHTH reported 11,500 cases of human trafficking nationwide based on nearly 50,000 contacts. This included over 10,000 calls directly from victims of human trafficking, plus 13,000 from concerned community members. The vast majority of these cases—8,248—were sex trafficking, 1,236 were labor trafficking, 505 were combined sex and labor trafficking, and 1,511 were not specified. The overwhelming majority (9,357) were cases of human trafficking involving female victims, and most (6,684) were adults over the age of 18 (NHTH, 2019). Global estimations of labor trafficking involve nearly 25 million people worldwide, 16 million of whom are likely in private industry. This means that many goods and services purchased within the US may be made by forced or child labor, giving consumers the power to fight human trafficking every day by avoiding these products and decreasing the demand for labor trafficking (NHTH, n.d.-b). The Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB, 2020) lists goods produced via forced or child labor across 76 countries. Two hundred eighteen million children ages 5-17 years are working globally, and 152 million of these cases are considered child labor. According to the 2020 ILAB report, China currently leads with 17 goods produced by forced labor, including artificial flowers, cotton, hair products, bricks, electronics,

...purchase below to continue the course

Although the cultural norms regarding labor amongst those under 18 vary, three international conventions have attempted to clarify the legal conditions of child labor, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the International Labour Organization Conventions #182 and #138 (Greenbaum et al., 2017). Human trafficking has been identified within the US in many industries and locations, such as hotels/restaurants, cleaning services, construction, factories, agriculture, and salons or spas (Greenbaum et al., 2017; NHTH, n.d.-c).

Adult victims of sex trafficking are commonly maintained through force, fraud, or coercion, while minors engaging in commercial sex are automatically considered victims of sex trafficking regardless of force, fraud, or coercion due to their age. Trafficking may occur in sham massage parlors, escort services, residential brothels, strip clubs, hostess clubs, truck stops, or public streets. An estimated 1 in 6 endangered runaways is likely a victim of sex trafficking. According to global estimates, 4.8 million individuals are trapped for sexual exploitation (NHTH, n.d.-g). In most cases of human trafficking in the US and around the world, the victims are adolescent or young adult females (Human Sex Trafficking, 2017).

Federal Legislation

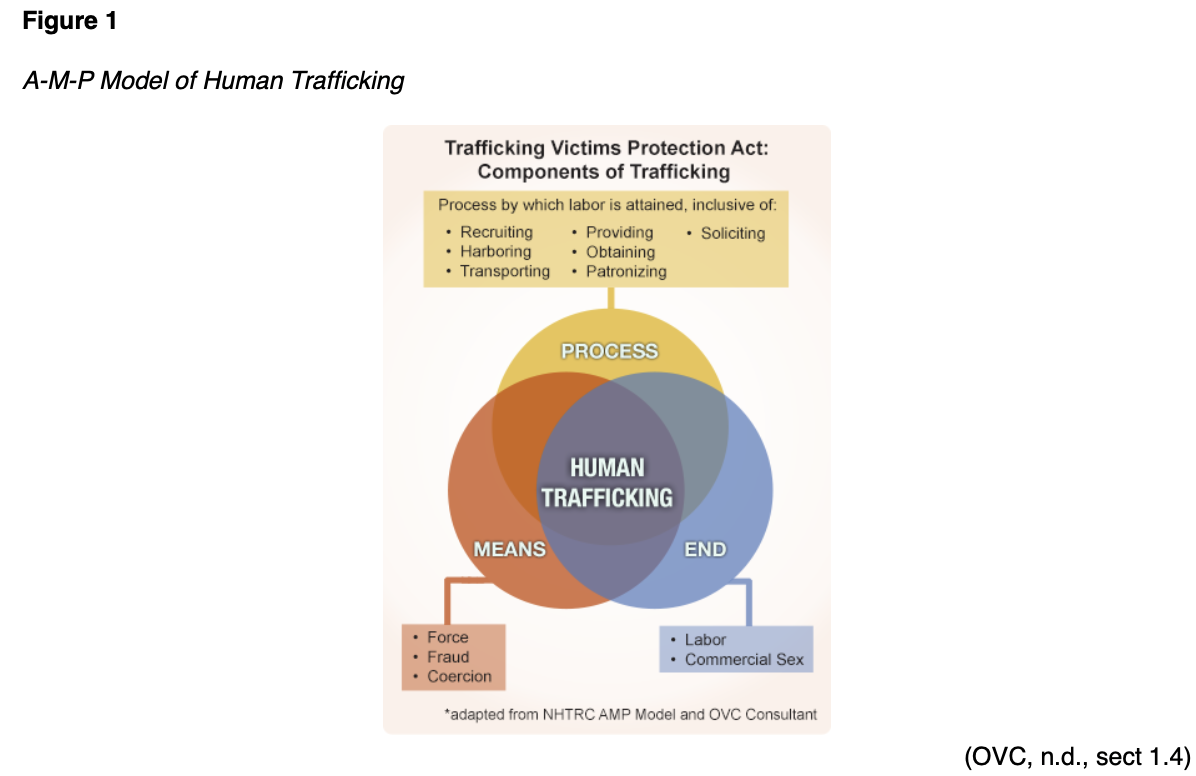

The Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) of 2000, which can be referenced fully by searching for 22 U.S.C. §7102, was the first comprehensive federal law regarding human trafficking or trafficking in persons (TIP) in the US (NHTH, n.d.-a; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020; TVPA, 2000). It has been reauthorized five times since that date (NHTH, n.d.-a). Revisions have further defined human trafficking as severe forms of trafficking in persons, including both sex and labor trafficking (Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020, p. 3). As defined by this legislation, there are three essential components, comprising the A-M-P model: action (what is done, referred to below as process), means (how it is done), and purpose (why it is done, referred to below as end; Figure 1). The means are not required to qualify as human trafficking if the victim is a minor (OTP, 2017; OVC, n.d., sect 1.4; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC], n.d.). At least one item from each of the three components must be present to establish a case for human trafficking of an adult (NHTH, n.d.-g). In addition to the means included in Figure 1, traffickers may utilize abduction, deception, abuse of power, or the provision of payments or benefits. Their purpose may also include slavery, removal of organs, or other types of exploitation (UNODC, n.d.).

The TVPA (2000) established a three-pronged approach to TIP (often referred to as the 3Ps or the three pillars): protection, prosecution, and prevention. The protection approach establishes federally-funded benefits for victims and survivors of trafficking, such as health care and T visas, aimed at protecting these individuals from deportation. These protective measures also help reintegrate survivors into society to avoid re-victimization. Prosecution refers to the addition of financial restitution payments by the TVPA in 2000 and more substantial penalties for convicted traffickers. Finally, prevention includes international incentives targeted at deterring TIP by improving economic conditions throughout the world. The TVPA created a new department (The Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons) within the US State Department and mandated annual TIP reporting. Finally, the TVPA required the formation of an interagency task force to address human trafficking (Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020, p. 2-3; TVPA). Then, the Obama Administration signed the Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act (2014), which required states to improve their policies and programs to better identify, document, and provide services for children at risk for sex trafficking. In addition, a 2015 act was passed regarding improved and consistent training of HCPs regarding how to assess for and manage victims of human trafficking (Leslie, 2018).

Most recently, the National Action Plan (NAP) to Combat Human Trafficking (2020) called on the US Department of Justice to enhance education and outreach via the production and dissemination of culturally sensitive and age-appropriate educational tools that augment existing prevention efforts. A working group was recommended to study the potential role of demand-reduction strategies and protection for workers on non-immigrant visas within the Senior Policy Operating Group (SPOG). The NAP called upon the Office of the US Trade Representative to ensure that products created using forced labor are not imported into the US. Protection enhancements include developing and updating human trafficking screening forms by the SPOG to be made available to all federal officials, HCPs, social workers, and other front-line workers, along with victim-centered training to respond appropriately. A public awareness campaign was recommended to increase victim identification and directly provide victims with information on seeking help. The NAP called on the justice system to protect trafficking victims from incarceration or other criminal penalties. It also supported the provision of financial remedies for victims through the Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act. The prosecution pillar requires improved coordination among law enforcement agencies to target, dismantle, and hold complex trafficking networks accountable. The NAP also advised law enforcement to develop and encourage advanced training to investigate and prosecute these criminals and deploy a broader range of non-criminal tools and federal enforcement options such as civil forfeiture actions, sanctions, travel restrictions, and enforcement of reporting requirements. The NAP also included a fourth “crosscutting” pillar to improve the collaboration and coordination of the three initial pillars by increasing understanding of human trafficking, information sharing, and incorporating survivor input (NAP to Combat Human Trafficking, 2020).

Impacts of Human Trafficking

From 2003 onward, studies have attempted to identify the effects of human trafficking on survivors (Powell et al., 2017). A systematic review in 2016 included 31 studies, which determined that victims of human trafficking experience an increased level of violence. Physical health symptoms reported most often by victims included headaches, abdominal pain, and back pain. Common mental health conditions identified include depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Victims of human trafficking self-report symptoms suggestive of a higher-than-average prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), although serological evidence of this trend is lacking. Many of the studies contained methodological weaknesses and differences in their definition and operationalization of trafficking (Ottisova et al., 2016). Studies in Asia and Africa estimate that women and girls who experience forced sexual encounters are 50% more likely to acquire HIV than women and girls who are not. This may be due to inadequate condom use, immature cervical epithelium, or cervical ectopy leading to microscopic breaks and inflammation in the vaginal mucosa. In addition to STIs, female victims have increased risks of pregnancy, urinary dysfunction/infection, and complications related to forced tampon use. Often referred to as “packing of the vagina,” victims may be forced to insert tampons before sexual encounters while menstruating, leading to foreign debris and reports of lost tampons requiring medical assistance for removal (Greenbaum et al., 2017; Hachey & Phillippi, 2017; National Human Trafficking Resource Center [NHTRC], 2016a; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020).

Victims of labor trafficking often present with signs of severe dehydration, malnutrition, heat exhaustion, or hypothermia. They often experience neck or back injuries, carpal tunnel syndrome, or vision problems due to a lack of proper safety equipment. They are at increased risk of infectious diseases due to overcrowded and unsanitary living or travel conditions. This may lead to the acquisition of tuberculosis (TB), typhoid, malaria, silicosis, Chagas disease, toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, cysticercosis, scabies, lice, or other skin infections. Skin infections with Vibrio vulnificus, a bacterium often encountered by migrant workers in warm climates exposed to shallow coastal waters, can lead to necrotizing fasciitis and eventually septicemia. Human trafficking increases the risk of chronic pain, substance use disorder and related complications, sleep disorders, chronic medical conditions, and self-harm or suicide. Chronic conditions that are caused or escalated due to extreme stress are common among trafficking victims, such as cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension, acute respiratory distress, constipation, and irritable bowel syndrome. As a less visible but equally damaging indicator, victims typically report a diminished quality of life and long-term fear of autonomy or independence (Greenbaum et al., 2017; Hachey & Phillippi, 2017; NHTRC, 2016a; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). Trafficked children are often deprived of adequate shelter, safety, sleep, exercise, balanced nutrition, clean water/air, appropriate clothing/shoes, and hygiene/sanitary products. The trauma leads to significant and lifelong mental, emotional, and physical effects, including PTSD, severe affective disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder), attachment disorders, depersonalization, dissociation disorders, and extreme stress and adjustment disorders. Children will often display evidence of significant delays in physical and cognitive development and impaired social skills (NHTRC, 2016a; Wood, 2020). One disorder that is described often by trafficking victims is memory disruption, whereby the victim’s recollection of events becomes disjointed, decreased, or inaccurate, especially surrounding traumatic events. Alternatively, many victims develop a phenomenon referred to as trauma bonding or Stockholm syndrome, in which they develop loyalty to and concern for the trafficker(s), refusing to report or testify against them and returning to their previous state of bondage when able (NHTRC, 2016a, 2016b).

Risk Factors for Human Trafficking

Anyone—in any community, in any country—can become a victim of human trafficking. However, certain groups have more significant risks of experiencing human trafficking than other groups. People of color and members of the LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, transgender, queer/questioning) community are more likely to become victims than others. This may be due to several factors, such as generational trauma, historical oppression, and discrimination. Populations at increased risk also include those residing on Native American reservations (NHTH, n.d.-d; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). Minors are inherently at increased risk for human trafficking due to their incomplete development and immature brains (Wood, 2020). Individual factors that increase the risk of victimization include:

- individuals with a disability

- an unstable living condition/homeless

- history of experiencing violence (e.g., domestic or sexual violence, intimate partner violence, gang members, or others exposed to community violence)

- a minor who has run away from home

- a minor involved in the juvenile justice or child welfare system

- undocumented or recent immigrants or those with a language/cultural barrier

- poverty or economic need

- those with a substance misuse disorder or addiction

- those with a caregiver or family member with a substance misuse disorder (NHTH, n.d.-d, 2019; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020)

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) increase the likelihood of risk-taking behaviors, which then predispose an individual to trafficking situations. The landmark study by Felitti and colleagues (1998) originally proposed this connection, correlating high scores on an ACE questionnaire with an increased risk for victimization and poor outcomes. It has since been confirmed with subsequent research. The original work focused on psychological, physical, and sexual abuse; violence against the mother; or living with individuals with substance use disorder, severe mental illness (including suicidality), or imprisonment. These childhood exposures, or ACES, significantly increase the risk for adult alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, smoking, poor self-rated health, obesity, inactivity, STIs, depression, suicidality, and many common chronic diseases (ischemic heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, and liver disease). Moreover, the number (quantity) of exposures increased that risk further (Felitti et al., 1998).

A 2017 study found that a prior history of sexual abuse was the most reliable predictor for individual exploitation via human trafficking. This history increases the risk of substance abuse and mental health disorders. It may also damage the assault victim’s concept of social norms, belonging, and family and engender feelings of distrust toward authority figures. All of these reactions are potential vulnerabilities or weaknesses that perpetrators may exploit. Higher ACE scores may contribute to the increased trafficking risk of members of the LGBTQ+ community (Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). The 2019 Data Report by NHTH and the Polaris Project indicated that the top risk factors for experiencing sex or labor trafficking also include a history of mental or physical illness and highlighted the elevated risk of those with substance use disorder or a recent history of migration or relocation (NHTH, 2019).

Identifying the perpetrators of human trafficking, often referred to as traffickers, can be more difficult than identifying victims. Traffickers may be of any race, nationality, gender, age, or sexual orientation. They may be related to the victim, even close family members or partners, or they may be strangers (NHTH, n.d.-d). They may be US citizens or foreign nationals. Traffickers prey on lost individuals who are searching for a better life and make false promises to them (e.g., of a loving relationship, a good job, safety/protection, or new opportunities), manipulation, and exploitation. They may work alone or for a larger, organized network. Traffickers may share the same national, ethnic, or cultural background as their victims, lending insight and understanding regarding their vulnerabilities and making the process of exploitation easier (NHTH, n.d.-h). Traffickers may also be young girls trained to recruit other young girls after being in the life for so long and gaining rank (RF, personal communication, August 11, 2021). The 2019 Data Report by NHTH and the Polaris Project showed that the top five recruitment tactics used by perpetrators of sex trafficking in 2019 consisted of an intimate partner/marriage proposition, familial tactics, a job offer advertisement, posing as a benefactor, or false promises/fraud. Perpetrators of labor trafficking were most likely to use a job offer advertisement, false promises/fraud, smuggling-related tactics, familial tactics, or posing as a benefactor (NHTH, 2019). The high profits associated with TIP are a significant motivator for the perpetrators, with a relatively low level of associated risk in most circumstances. While a stereotypical trafficker is affiliated with a gang or functioning as a pimp, many traffickers often publicly masquerade as small business owners or employers, such as:

- massage parlor or brothels

- cleaning services

- domestic assistants

- landscaping companies

- agriculture administration- managers and site supervisors

- labor brokers

- factory owners/managers

- nail salons/spas

- international matchmaking services (“mail-order bride”)

- modeling agencies

- au pair agencies

- strip clubs (ICE, 2017; NHTH, n.d.-h; NHTRC, 2016b)

Most traffickers target vulnerabilities and sell a dream to recruit victims. These dreams often include red flags, such as a job opportunity that sounds too good to be true, an employer who refuses to answer detailed questions or provide an employment contract, or an employment contract provided in a language that the employee cannot read. Labor traffickers may request payment from an employee victim before starting work. Sex trafficking victims may suddenly be coerced into a highly asymmetric relationship (i.e., a significant difference in age or financial/social status) with copious amounts of expensive gifts or money (NHTH, n.d.-d).

Aside from violence and forced migration, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP; Greenbaum et al., 2017) has noted additional family factors such as poverty and unemployment that increase the risk of trafficking of minor children. In addition to the violence mentioned previously, community factors that increase this risk include a tolerance of sexual/labor exploitation within the community, natural disasters, community upheaval, high demand for inexpensive labor, a lack of community resources or support, and a lack of awareness among community members regarding trafficking practices. The AAP highlighted societal risk factors like gender-based violence and discrimination, cultural beliefs or stigma, a weak recognition of child rights within society, and political or social unrest (Greenbaum et al., 2017).

Traffickers often exploit, intersect with, or exist alongside legitimate businesses for their space, transportation services, or other resources to facilitate their trafficking system. This includes the use of advertising companies, transportation providers (e.g., airlines, buses, rail, taxis), money transfer services, and hotels or motels, amongst others. Owners and operators of these businesses have the ability and moral obligation to recognize and report when their services are being misused (NHTH, n.d.-h).

Identification of Victims/Survivors in Healthcare Environments

The majority (over 85%) of trafficking victims report accessing healthcare services during their period of trafficking. While most victims report accessing care via an emergency department, HCPs in other settings must all be aware of and watchful for the indications of possible TIP, including primary care offices, pediatric offices, gynecology/obstetrics, health departments, urgent care clinics, and school nurses (NHTRC, 2016b; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). Trauma-informed care requires the entire multidisciplinary healthcare team to recognize “the scope of the impact of the trauma on an individual victim’s lifespan and lessens any chance of inflicting more injury on this victim.” A victim-centered approach attempts to ensure that the victim is not re-traumatized or re-victimized and is defined as “the precise focus of attention, catering to the needs of the victim to ensure delivery of care in a compassionate, culturally sensitive, linguistically appropriate, nonjudgmental, and caring manner. A victim’s wishes, safety, and well-being are considerations” (Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020, p. 28). The “rescue” may not be to remove an adult victim from their situation that day, but rather to provide them with resources for when they are ready to exit the life (RF, personal communication, August 11, 2021).

The acronym SOAR may help HCPs in all settings to identify and respond appropriately to human trafficking in the healthcare setting: stop, observe, ask, and respond. Stop asks HCPs to pause and recognize the scope of the human trafficking problem in the US. Observe refers to the awareness of verbal and non-verbal indicators of trafficking to help HCPs identify those at risk. Ask indicates that the HCP should listen to the victim’s responses to questions carefully, providing victim-centered and trauma-informed care. Finally, respond refers to identifying needs, knowledge of available resources, and provision of support or assistance when requested. SOAR training is available online through the US Department of Health and Human Services (train.org) for free to HCPs and confers 1 contact hour of continuing professional development credit (OTP, 2019). Overall, the goal of the HCP should not be to rescue the victim or convince them to disclose but rather to establish a safe and nonjudgmental space to facilitate the proper identification of victims and provide them with whatever assistance they require or request (NHTRC, 2016a).

Victims may seek care for related injuries, after assaults or injuries, or for unrelated or preexisting conditions. However, victims rarely self-identify, even to HCPs whom they trust; this may be attributed to feelings of shame or guilt; fear of retaliation by their trafficker; fear of arrest (with a prior criminal record), deportation, or report to social services; a lack of transportation or controlled movement; or a lack of understanding of the US healthcare system (Hachey & Phillippi, 2017; NHTRC, 2016b; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). There may also be a language barrier present, distrust of authority figures, stigma regarding their situation, or another underlying cause (Human Sex Trafficking, 2017). Victims may feel partially responsible for their current situation or be concerned about large financial debts that may cripple themselves or their families if not paid. Victims may lack insight by not recognizing their current situation as exploitation due to brainwashing by their trafficker into thinking the situation is “normal” or of their choosing. They may be unable to view their trafficker as an abusive perpetrator, especially if that individual is a family member or “romantic partner” (Wood, 2020). Traffickers may also “test” their victims by allowing them to be questioned to assess their loyalty (Leslie, 2018). Victims of labor trafficking may feel trapped due to debts owed to their employer, immigration status, or threats of violence. Trafficking victims often do not have possession or control of crucial documents (e.g., their driver’s license, birth certificate, passport, or immigration paperwork/visa) and have few personal possessions (Leslie, 2018; NHTH, n.d.-d).

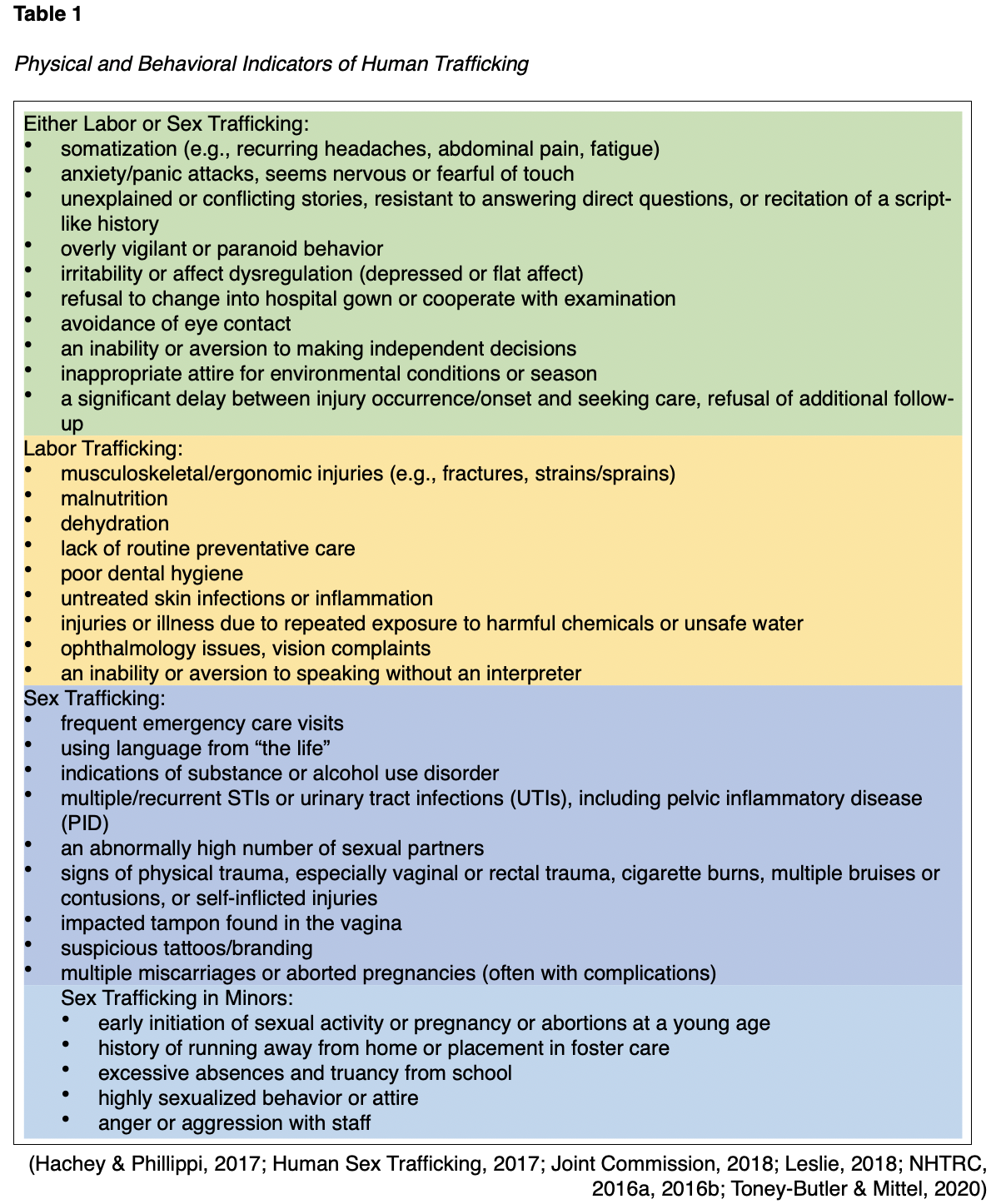

Trafficking victims may have a significant discrepancy between their reported and suspected age (Leslie, 2018). They are typically isolated from others or may be living in dangerous, overcrowded, or unsanitary conditions. Trafficking victims often live where they work or are accompanied by guards while being transported to and from work (NHTH, n.d.-d). Victims of labor trafficking are often abused or threatened at work, restricted from taking breaks, and denied adequate personal protective equipment (PPE); they also report being recruited for different work than they are currently doing (NHTRC, 2016a). Trafficking victims may be unable to recite their address or explain where they live; they often claim they are “just visiting” the area (Joint Commission, 2018; NHTRC, 2016a; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). They may be accompanied by a partner, guardian, or “sponsor” who will not allow them to be alone with anyone else, including HCPs, and will often answer questions for the patient (NHTH, n.d.-d; NHTRC, 2016a). An accompanying family member who is rude, impatient, or anxious to leave, or a victim who leaves without being seen or against medical advice, may indicate a trafficking situation. The restrictions on trafficking victims may be invisible if they are emotional and psychological, as traffickers often utilize fear, threats, and mental control. Based on the SOAR acronym mentioned above, these indicators are best identified when the HCP takes the time to stop, observe the patient (including verbal and nonverbal cues, which may be subtle), and ask open-ended, nonjudgmental questions in a private setting (OTP, 2019; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). Table 1 provides a summary of the indications that suggest human trafficking.

HCPs should avoid stereotyping patients as criminals, prostitutes, difficult, uncooperative, or drug-seeking. Instead, they should consider that these patients could be potential victims who require a careful and nonjudgmental assessment of their needs. HCPs should also recognize there is no “perfect” victim, as no victim fits an exact or predetermined model (Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). Instead, any patient presenting with the above indication(s) of human trafficking should be screened. Documentation regarding any injuries should be detailed, including the size, shape, color, location, and pattern of bruising, lacerations, contusions, scars, or other indications of trauma (Hachey & Phillipi, 2017; Leslie, 2018). Proper documentation, potentially including photos, may prove vital and allow the victim to prosecute their trafficker successfully at a later date (Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). Because nurses obtain a medical history for diagnosis and treatment, they can testify in court utilizing the history on behalf of the patient under the medical exemption to hearsay. This unique ability that nurses have may make the difference in delivering justice or saving a life (RF, personal communication, August 11, 2021). Proper documentation also communicates the concerns to other healthcare team members if the patient returns for future visits (Joint Commission, 2018). Before any screening interviews, the patient’s basic needs should be met, and they should be reassured of their current safety (NHTRC, 2016b). Patient statements should be placed in quotes, and specific details of patient demeanor, tattoos, and clothing, etc., should be documented, as well as any names stated for safety purposes (RF, personal communication, August 11, 2021). The HCP should be prepared for the patient to respond with various trauma responses, including anxiety, mood fluctuations, aggression, shame, guilt, detachment, hopelessness, fear, or hypervigilance. Victims may appear easily startled, jumpy, reserved, or hesitant (National Human Trafficking Training and Technical Assistance Center [NHTTAC], 2018).

Screening for Victims of Human Trafficking

A multidisciplinary approach using all available resources has proven to be most effective, especially teams that include experienced social workers. Collaboration and communication across the healthcare team, community service providers, law enforcement, and investigators increase the chances that all victims' needs are met efficiently and effectively. Institutions and organizations should carefully establish multidisciplinary protocols and policies regarding the care of trafficking victims, and HCPs should refer to them as needed. Professionals expected to identify and care for trafficking victims should be trained adequately to effectively recognize red flags, establish professional rapport, use screening tools, and provide a trauma-informed response. Protocols help educate HCPs on identifying and responding to victims, increasing the likelihood that victims will be identified and assisted. Without clear protocols, the identification and response require the HCP to rethink their response anew each time, becoming a stressful waste of time and increasing the victim's anxiety (Greenbaum et al., 2017; Joint Commission, 2018; NHTRC, 2016a; NHTTAC, 2018). Protocols should include common indicators and red flags, strategies to provide privacy when interacting with patients, interview techniques, safety strategies for the patient and the healthcare team, and referral or resource information. Mandatory reporting guidelines, NHTH contact information, and follow-up data should also be included. Some protocols may also establish staff training requirements and assessments (Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). Information on accessing interpreter services should also be included in institutional policies to ensure that they are used consistently (NHTTAC, 2018). When developing truly victim-centered protocols, some researchers advocate for the inclusion of survivors on the strategic planning committee (Davies, 2007). The National Survivor Network is a reliable resource for local survivor leaders to serve as knowledgeable and trusted voices and resources to ensure appropriate and comprehensive protocols (Baldwin et al., 2017). It is essential that hospital staff are trauma-informed as well as survivor informed. Once the staff is trained and protocols are being carried out, institutions should regularly and methodically assess their effectiveness and modify them when needed. Despite this guidance, each situation will be unique to the particular victim, and the response should be tailored to their scenario and needs. If questions arise, health professionals have 24/7 access to assistance through the NHTRC hotline for guidance and determining the next steps. They also offer tele-interpreting services for over 200 languages (Joint Commission, 2018; NHTRC, 2016a; NHTTAC, 2018).

As previously mentioned, victim-centered care should be both culturally and linguistically tailored to the patient whenever possible. If English is not the patient’s primary language, they should be offered the use of a professional, competent interpreter who is not related to or accompanying the patient. Interpreters should have signed confidentiality and nondisclosure agreements. In addition to providing a more efficient interview by communicating in the patient’s native language, an interpreter may also provide valuable insight by identifying subtle cues and inconsistencies in the patient’s story and enhancing the patient’s overall comfort level by easing cultural shock. The patient should be given the option of being interviewed by someone of the same gender if desired, and a similar choice regarding interpreters should be offered whenever possible. If possible, patients should be matched with service providers and case managers of the same ethnicity or cultural background to help overcome language barriers and heighten the level of cultural sensitivity, as well as referencing the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) for additional guidance (NHTRC, 2016a; NHTTAC, 2018; Simich et al., 2014; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020).

A checklist of red-flag indicators is insufficient as a screening technique. Patients identified as high-risk based on a red-flag checklist should be given a screening interview. While validated screening tools for HCPs are in relatively short supply, they are available. The Trafficking Victims Identification Tool (TVIT) by Simich and colleagues (2014) is based on 2 years of research conducted by the Vera Institute, an independent nonprofit, and funded by the National Institute of Justice. This tool has been validated with labor and sex trafficking victims, men and women, and US-born and foreign-born victims. It was not validated with individuals with disabilities or LGBTQ+ individuals. It is an interview tool consisting of 16 core questions (a short version) and 4 additional questions regarding migration to be used with individuals born outside the US. The accompanying manual gives specific suggestions to optimize the tool’s effectiveness, such as fulfilling the victim’s basic needs before interviewing them (e.g., food, water, clothing, medical care) and performing the interview in a private, secure, comfortable location away from and out of view of the potential trafficker in a professional yet friendly manner. The patient should be told the purpose and length of the interview at the beginning. The interviewer should reassure the patient by recounting their prior experience with similar cases; be patient, caring, and sensitive to the patient’s needs; avoid placing any blame or responsibility on the victim; allow the patient sufficient time to tell their story in their own words; and remain mindful and respectful of the patient’s cultural background. Expressing sorrow or empathy is encouraged, but the nurse should avoid appearing judgmental or shocked. All interviews should be confidential, and the patient should be aware of this information from the beginning of the interview. If a mandatory reporter, the nurse should explain their requirements to report, if applicable. In some jurisdictions, certain portions or details of the interview may be deferred to a service provider (e.g., attorneys or clergy members) who can legally claim privileges (Simich et al., 2014). Nurses in Texas are required to report any suspicion of abuse or neglect involving a minor within 48 hours of this suspicion, and attorneys and members of the clergy are not privileged and therefore also mandated to report any suspected abuse of a minor in that state (Texas Family Code, 1995/2017). The TVIT refers to “work or other activities” regarding sexual services and informal work. However, victims may not conceptualize forced prostitution (rape), forced shoplifting, or forced drug smuggling as work. The interviewer should attempt to mirror the patient’s own words and terminology throughout the interview whenever possible. The long and short versions of the TVIT and the accompanying user guide can be accessed on the Vera Institute’s web page at Vera.org (Simich et al., 2014). Critics of the TVIT report that the short version takes longer than an hour to administer, not including the time required to establish a rapport with the patient before administration. They also warn that this tool has not been validated for use in multiple settings (as it was validated only for use within victim service organizations), potentially making it inappropriate for use in public health (NHTTAC, 2018).

The NHTTAC (2018) has also developed a toolkit along with their Adult Human Trafficking Screening Tool (AHTST). This 8-question verbal screening tool is designed to be used by HCPs and members of the behavioral health, social service, and public health sectors, but it is not yet validated. They recommend screening patients who are considered at-risk based on an established red-flag checklist of signs, symptoms, and indications of potential human trafficking. The goals of the AHTST are to help recognize the signs of trafficking, respond appropriately, and make the appropriate referrals. It is an evidence-based, survivor-centered, and trauma-informed tool. This means that it is designed to:

- recognize the effects of violence on human development and coping

- ensure that services are accessible and readily available

- identify co-occurring problems comprehensively

- ensure that services are culturally and linguistically appropriate

- minimize the possibility of re-traumatizing

- emphasize education, choice, and resilience (NHTTAC, 2018, p. 6)

As mentioned above, the NHTTAC user guide stresses the importance of developing and establishing institutional policies and a referral network or plan before screening patients within their institution. The user guide suggests first establishing a trusting relationship before the screening interview if possible (with tips included in Table 1 of the NHTTAC user guide) and maintaining a neutral attitude toward the trafficker throughout the interview. Victims often react by defending the trafficker if they are criticized or condemned by the interviewer, so accusatory language should be avoided. In addition to conducting the interview in a safe place and addressing the patient’s physical needs first as described above, the user guide suggests utilizing open, non-threatening body positioning (e.g., remain at eye level, sit or squat, respect personal space, and avoid crossing the arms), engaging the patient (e.g., maintain a calm tone of voice and a warm and natural facial expression, make eye contact), matching their pace and mirroring their language, offering an interviewer of the same sex, and avoiding probing for unnecessary details. Calm, empathetic, and respectful language should be used, and the interviewer should allow themselves and the patient ample time and avoid rushing through the screening interview. The following eight questions are included in the AHTST (NHTTAC, 2018, pp. 16-17):

- Sometimes lies are used to trick people into accepting a job that doesn’t exist, and they get trapped in a job or situation they never wanted. Have you ever experienced this, or are you in a situation where you think this could happen?

- Sometimes people make efforts to repay a person who provided them with transportation, a place to stay, money, or something else they needed. The person they owe money to may require them to do things if they have difficulty paying because of the debt. Have you ever experienced this, or are you in a situation where you think this could happen?

- Sometimes people do unfair, unsafe, or even dangerous work or stay in dangerous situations because if they don’t, someone might hurt them or someone they love. Have you ever experienced this, or are you in a situation where you think this could happen?

- Sometimes people are not allowed to keep or hold on to their own identification or travel documents. Have you ever experienced this, or are you in a situation where you think this could happen?

- Sometimes people work for someone or spend time with someone who does not let them contact their family, spend time with their friends, or go where they want when they want. Have you ever experienced this, or are you in a situation where you think this could happen?

- Sometimes people live where they work or where the person in charge tells them to live, and they’re not allowed to live elsewhere. Have you ever experienced this, or are you in a situation where you think this could happen?

- Sometimes people are told to lie about their situation, including the kind of work they do. Has anyone ever told you to lie about the kind of work you’re doing or will be doing?

- Sometimes people are hurt or threatened, or threats are made to their family or loved ones, or they are forced to do things they do not want to do in order to make money for someone else or to pay off a debt to them. Have you ever experienced this, or are you in a situation where you think this could happen?

For each of these queries, the interviewer should note how the patient responds in the center column (yes, no, I don’t know, or declined to answer) and any essential notes/details in the final column. A single affirmative answer may indicate that the individual is at risk of or currently being trafficked. The nurse should be prepared to help deescalate if the screening interview triggers a trauma reaction in the patient. Common grounding techniques that may be helpful include 4-7-8 breathing (the patient inhales through the nose with a closed mouth for the count of 4, holds their breath for a count of 7, and then exhales through their mouth with the tip of their tongue pressed against the roof of their mouth, making a whoosh sound, for a count of 8, then repeat) or the 5-4-3-2-1 game (ask the patient to name five things that they can see, four that they can feel, three that they can hear, two that they can smell, and one good thing about themselves). After the interview, the nurse should conclude by discussing the patient’s primary concerns, their interest in additional referrals, and the importance of a safety plan. Obvious shortcomings identified within the AHTST include its limitation in screening for adult victims only and its current lack of validation (NHTTAC, 2018). Similar non-validated screening tools have also been suggested (Byrne et al., 2017; Hachey & Phillippi, 2017; Leslie, 2018; Mumma et al., 2017).

If the patient declines to participate in a screening interview, the nurse should ask permission (if it is safe) to give the patient information, including contact details for the NHTH, to look over at another time. Institutions should develop and maintain printed materials with contact information for local resources. A small shoe or key card may be provided and hidden in the patient’s shoe or another discrete location. If the patient does not feel that having the phone number or printed information is safe, assist the patient in memorizing the hotline number for later use if desired. The number is easiest to remember by separating it in the following manner: 888-3737-888. The patient should be reminded that the NHTH is completely confidential unless the caller threatens to harm themselves or others, is in imminent danger, or is experiencing a life-threatening emergency (Joint Commission, 2018; NHTRC, 2016b, 2016a; NHTTAC, 2018; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). The HCP can also utilize recommended messaging techniques for victims of human trafficking, such as the following (Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020, p. 21):

- We are here to help you, and our priority is your safety. Our goal is to keep you safe and protected.

- We can provide you with the medical care that you need and find you a safe place to stay.

- Everyone has the right to live without being abused or hurt, and that includes you.

- You deserve a chance to live on your own and take care of yourself, be independent, and make your own choices. We can help you with that.

- We can try to get you help to protect your family and your children.

- You have rights and deserve to be treated according to those rights.

- You can trust me. I know it’s hard to know who to trust. I will do everything within my power to help you. Assistance is available for you under the law, and there are special visas to allow you to live safely in this country.

- No one should have to be afraid all the time. We can help.

- Help us, so this does not happen to anyone else.

- You can decide what is best for you.

Trauma-Informed Care: Response, Referrals, Resources, and Reporting

In addition to the suggestions mentioned in both of the toolkits discussed above, the NHTRC (2016b) also recommends that HCPs attempting to deliver victim-centered care should remain sensitive to power dynamics throughout their interactions with the patient and intentionally avoid re-traumatization by imposing their will and preferences upon the patient or probing for unnecessary details. For example, offering a victim multiple options throughout the day for their upcoming interview appointment or the ability to meet with a provider/agent of a particular gender may provide the victim with a crucial sense of control, decrease their vulnerability, and lead to improved interactions and communications between the victim and the care team. HCPs, by the nature of their role/position, knowledge, and education, are in a position of both power and influence over the survivor. This is often compounded by culture and socioeconomic status. The HCP should recognize that this position comes with privilege and a responsibility to use that power to assist and empower the survivor while avoiding misusing that power, even unintentionally (Davies, 2007). A survivor may be re-traumatized by a lack of control, an unexpected change, or feeling frightened, threatened, attacked, judged, shamed, or vulnerable. A trauma-informed approach involves understanding trauma's social, physical, and emotional impact on the victims and the professionals helping them. This understanding requires (a) realizing the prevalence of trauma, (b) recognizing its effects on everyone involved, and (c) application of this knowledge in practice. The OVC (n.d.) offers a free online Victim Assistance Training (VAT) on trauma-informed care for victim service providers and allied professionals through their site, ovcttac.gov.

Institutional protocols will help guide appropriate behavior following a positive screen for potential human trafficking (NHTRC, 2016b). Various resources should be offered to the patient once primary medical care has been provided. This may include referrals to local support, resources, and services, as well as the option to report the incident(s) to law enforcement. Concerns regarding the patient’s mental health based on the administration of the screening tool should trigger an immediate referral to an appropriate mental health provider available locally (NHTTAC, 2018, p. 7). The NHTRC/NHTH offers a massive referral network with an online referral directory for this purpose on their website. They can facilitate connections with anti-trafficking organizations, legal service providers, shelters, and trained local social service agencies (NHTH, n.d.-e). Many metropolitan areas in the US also have Human Trafficking Task Forces established to connect with local resources (Joint Commission, 2018). Beyond medical care, examples of expected needs experienced by human trafficking victims include clothing, food, and housing, which may be obtained through a local homeless shelter or crisis center. Victims often request assistance locating and contacting friends or family. Victims may require transportation, employment services (e.g., job training), crisis intervention, case management, and life skills training. Legal services can help address issues related to immigration, child custody, and legal defense for prostitution/drug or other related charges (NHTRC, 2016b). The local Rescue and Restore Coalition (if available) and the HT Pro Bono Center may provide legal referral sources locally (Baldwin et al., 2017). Malnourished patients should be referred to a dietician, while other patients with specific health concerns (communicable disease, pregnancy, infertility, unwanted tattoos/branding, irritable bowel syndrome, substance use disorder) should be referred to the appropriate corresponding specialists (infectious disease, obstetrics and gynecology, dermatology, plastic surgery, gastroenterology, addictionology) as needed (Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). Beyond their immediate needs, victims of human trafficking should be referred to a local administrator for the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA), which offers victim compensation to reimburse them for crime-related costs and lost wages (OVC, n.d.).

As mentioned earlier, the interviewer should be forthcoming and upfront regarding any mandatory reporting requirements within their state or jurisdiction. Nurses must report any suspicion of child maltreatment and may also be required to report domestic violence, although regulations vary by state for adult victims. In some states, reporting is mandatory if serious bodily injury or a firearm is involved. A nurse who is unsure can confer with www.victimlaw.org to find the mandatory reporting laws in their state. Otherwise, the interviewer should obtain consent from adult victims before disclosing any personal information to others, including referring service providers. HIPAA regulations also affect how and what information can be transmitted between care providers (NHTRC, 2016a; Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). With this consent (or if such action is mandatory), the interviewer or nurse should make the agreed-upon report to the appropriate state or local agency and contact the NHTH. Suppose reporting is not mandatory, and the patient does not wish to report the incident. In that case, the interviewer or nurse should provide any desired referrals for care or services and should contact the NHTH for additional guidance. Please note that contacting the NHTH/NHTRC does not fulfill the state and local mandatory reporting requirements (Joint Commission, 2018; NHTRC, 2016b). Furthermore, HIPAA was never designed to prevent the reporting of a crime and allows for the reporting of abuse under certain circumstances (if necessary, to avoid serious harm). Reports can be filed without identifiable patient health information (i.e., include the gender and age of the patient, along with the type of trafficking that is occurring; NHTTAC, 2018). Victims under 18 also have agency and opinions and should be allowed to participate in shared decision-making whenever possible (Wood, 2020).

Safety Planning

A safety plan for a human trafficking victim should assess their current risk, identify current and potential concerns, offer strategies to reduce or avoid the threat of harm, and involve concrete responses if safety is threatened. It should be individualized and include practical steps for the patient to keep themselves safe while in the current trafficking situation, if planning to leave or leaving, and after leaving. It may include coping skills, talking about the abuse with friends or family, and taking legal action. The nurse or provider helping the victim develop their safety plan should remember that the victim understands their situation best, and the nurse should honor their requests without questioning their motives or judgment. As suggested above, communication should be open and nonjudgmental when assessing and interviewing potential victims. Try to communicate in person, if possible, as traffickers can discover written communication or text messages. Phone calls are a reasonable second option if in-person communication is impossible, but the nurse should remain mindful that phone calls can be intercepted or overheard. A word or code can be established ahead of time to indicate if communication can proceed safely. Most importantly, the nurse or HCP should listen carefully to the victim’s concerns, needs, and wishes from this point onward (NHTH, n.d.-f; NHTTAC, 2018).

Safety plans may include simple steps, such as avoiding confrontations with their trafficker in the kitchen (due to the presence of knives) or around firearms and keeping copies of important documents and medicine in a safe place that can be retrieved quickly and easily. During violent encounters, the victim should be encouraged to avoid rooms with potential weapons (garage, basement, closet) and no exit. A code word or signal (e.g., flashing the front porch light three times) can be communicated ahead of time to a close neighbor or trusted friend to signal when the victim may be in danger. If this is discussed, the victim should be clear about what the neighbor or friend should do in that circumstance (call 911, send help, pick up the children, etc.). Children should be told that they are never responsible for protecting an adult, how to call for help if needed, and where to hide during violent incidents. Victims should be reminded to contact 911 if they ever encounter life-threatening or immediate danger. Safety apps, such as Circle of Six, Bsafe, and SafeTrek, may be downloaded to smartphones (NHTH, n.d.-f; NHTTAC, 2018).

When assessing the current level of risk or danger, the nurse should consider whether the trafficker is present at the medical facility and whether the patient is a minor. Traffickers may be female and appear to be of a similar age, accompanying the victim as a stated friend. The nurse should never assume that the individual accompanying a potential victim is safe, regardless of their appearance. The nurse should also ask the patient whether they believe anyone else, including their family, may be in danger and how they think the trafficker might respond if they do not return. If the victim is in immediate danger, law enforcement involvement may be the most appropriate safeguarding method. Law enforcement can assist with filing a formal report to initiate the prosecution process and providing immediate security via a protective (restraining) order (Joint Commission, 2018; NHTRC, 2016b; NHTTAC, 2018). Institutional policies may dictate when law enforcement is to be contacted, but this decision should be made in tandem with the patient whenever possible (NHTRC, 2016a). If law enforcement officers are participating or assisting, they should be dressed in civilian clothing with no visible weapons (Simich et al., 2014). The NHTRC can help facilitate a report to specialized law enforcement units trained to handle human trafficking or accept anonymous tips (NHTRC, 2016a, 2016b). Cultural barriers between survivors and the law enforcement community may make communication difficult. Survivors should be warned that they may feel an inevitable loss of control over the case after making a report to a law enforcement agency (Davies, 2007). The Department of Homeland Security (866-347-2423) or the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Lost Task Force (800-CALL-FBI) can be contacted to identify local officials and agents with expertise in HT during protocol development. Protocols should specify when certain officials should be contacted, depending on the specific details of the case. Many local law enforcement agencies have an anti-trafficking task force or a trained officer with expertise in trafficking. Local agencies should be asked to clarify their policy on arresting potential victims related to their trafficking victimization (e.g., prostitution, truancy), which may force agents to arrest victims with open warrants. Community-based diversion programs divert defendants facing criminal charges to avoid incarceration. Most of these programs allow for the dismissal of charges if completed and may include counseling, substance abuse treatment, and vocational training (Baldwin et al., 2017).

Safety planning should also consider the safety of the HCPs who are intervening in these situations. The NHTTAC (2018) suggestions include regular risk assessments and an updated risk management plan within the institution or organization, notification of a colleague regarding the provider’s whereabouts when conducting a screening, and periodic safety checks. Screenings conducted outside of a facility should have two staff members present. The screener should be alert at all times and aware of who may be within earshot. Confidential data and personal identification information should be handled professionally and disposed of confidentially (NHTTAC, 2018). All cell phones and other communication devices should be turned off, as traffickers may use these methods to keep tabs on the victim at all times. HCPs should never attempt to address the situation with the victim in front of the accompanying friend or family member, as they may be the trafficker or a “guard.” Collecting a urine sample or escorting the patient to the radiology department for an imaging study are useful methods of creating privacy and separation between the patient and an accompanying individual (Toney-Butler & Mittel, 2020). The NHTTAC (2018) recommends a simple explanation that “our policy allows only patients in this area during tests” (p. 32).

Suppose the victim is considering leaving the trafficking situation, and they are unsure of their location. In that case, they should attempt to use street signs, newspapers, magazines, pieces of mail, street numbers on buildings/mailboxes, or passersby to obtain as much information as possible regarding their whereabouts. The victim should plan an escape route in times of danger, with a backup if their path becomes blocked, and practice this route until memorized if possible. If there are children present, they should also be involved in planning and practicing the escape route. Medications, essential documents, and a prepared bag with a change of clothes should be easily accessible or hidden in a safe location to retrieve after leaving. Significant phone numbers should be written or memorized in case the victim’s phone is taken or damaged. An immediate plan for shelter should be arranged with a trusted family member or a friend or by contacting the NHTH to locate the closest crisis center or shelter (NHTH, n.d.-f; NHTTAC, 2018).

Survivors continue to be at risk of violence after exiting a trafficking situation. They should be educated on why and how to file a protective order against the trafficker(s), which may be done civilly in some locations without involving law enforcement if they would like to. Survivors should be counseled on options such as changing their phone number and avoiding sharing their new address or phone number except with a few trusted individuals. Typically, their phone belongs to their trafficker, or they may have multiple phones. They should consider accessing the Address Confidentiality Program, always keeping their doors locked, and always keeping their cell phone or an emergency phone on their person. Survivors should be advised to document any contact attempts made by the trafficker, including saving voice mails or text messages. A safety plan should be communicated to any children involved, detailing what they are to say or do if the trafficker attempts to contact them alone. As explained above, a code word or signal should be agreed upon ahead of time with a close neighbor or trusted friend to communicate if the survivor may be in danger and exactly how the individual should respond. Additional specific resources should be offered if appropriate, such as articles on rebuilding finances after leaving a financially abusive relationship (NHTH, n.d.-f).

The nurse should know what resources are available in the local community and how to access them. By building relationships with community partners, the nurse can quickly activate the “what is next” process when the need arises. The nurse should be familiar with the process of forensic/SANE exams. If the patient is an adult, they are not required to make a police report to obtain a SANE exam. The kit is saved and stored but not turned into the crime lab without the victim’s consent allowing them time to decide. This should be explained to the victim and may convince them to go through the evidence-collecting process (RF, personal communication, August 11, 2021).

Resources

The NHTH/NHTRC can be contacted 24/7 by calling 1-888-373-7888. They also accept text messages at 233733 and emails at NHTRC@polarisproject.org. They offer information, resources, an online reporting form, and an option for a live chat on their website: www.humantraffickinghotline.org or www.traffickingresourcecenter.org.

The Rescue America Hotline, 713-322-8000, has facilities across the nation with hands-on teams that meet the patient where they are to help get them directly to services they need. Their website can be accessed at www.rescueamerica.ngo

References

Baldwin, S. B., Barrows, J., & Stoklosa, H. (2017). Protocol toolkit for developing a response to victims of human trafficking in health care settings. HEAL Trafficking and Hope for Justice. https://healtrafficking.org/protocol-toolkit-for-developing-a-response-to-victims-of-human-trafficking-in-health-care-settings/

Bureau of International Labor Affairs. (2020). List of goods produced by child labor or forced labor. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ILAB/child_labor_reports/tda2019/2020_TVPRA_List_Online_Final.pdf

Byrne, M., Parsh, B., & Ghilain, C. (2017). Victims of human trafficking: Hiding in plain sight. Nursing, 47(3), 48–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000512876.06634.c4

Davies, J. (2007). Helping sexual assault survivors with multiple victimizations and needs. https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/Helping-sexual-assault-survivors-with-multiple-victimizations-and-needs_0.pdf

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

Greenbaum, J., Bodrick, N., & the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect, Section on International Child Health. (2017). Global human trafficking and child victimization. Pediatrics, 140(6). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3138

Hachey, L. M., & Phillippi, J. C. (2017). Identification and management of human trafficking victims in the emergency department. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal, 39(1), 31–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/TME.0000000000000138

Human Sex Trafficking. (2017). Women’s Healthcare, A Clinical Journal for NPs. https://www.npwomenshealthcare.com/human-sex-trafficking/

Joint Commission. (2018, June 18). Quick safety issue 42: Identifying human trafficking victims. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/newsletters/Newsletters/quick-safety/quick-safety-42-identifying-human-trafficking-victims

Leslie, J. (2018). Human trafficking: Clinical assessment guideline. Journal of Trauma Nursing: The Official Journal of the Society of Trauma Nurses, 25, 282–289. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTN.0000000000000389

Mumma, B. E., Scofield, M. E, Mendoza, L. P., Toofan, Y., Youngyunpipatkul, J., & Hernandez, B. (2017). Screening for victims of sex trafficking in the emergency department: A pilot program. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18(4), 616–620. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2017.2.31924

National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking. (2020). https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/NAP-to-Combat-Human-Trafficking.pdf

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.-a). Federal law. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/what-human-trafficking/federal-law

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.-b). Labor trafficking. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/type-trafficking/labor-trafficking

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.-c). Myths & facts. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/what-human-trafficking/myths-misconceptions

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.-d). Recognizing the signs. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/human-trafficking/recognizing-signs

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.-e). Referral directory. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/training-resources/referral-directory

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.-f). Safety planning information. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/faqs/safety-planning-information

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.-g). Sex trafficking. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/type-trafficking/sex-trafficking

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (n.d.-h). The traffickers. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://humantraffickinghotline.org/what-human-trafficking/human-trafficking/traffickers

National Human Trafficking Hotline. (2019). Hotline statistics. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/states

National Human Trafficking Resource Center. (2016a). Identifying victims of human trafficking: What to look for in a healthcare setting. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/sites/default/files/What%20to%20Look%20for%20during%20a%20Medical%20Exam%20-%20FINAL%20-%202-16-16.docx.pdf

National Human Trafficking Resource Center. (2016b). Recognizing and responding to human trafficking in a healthcare context. https://humantraffickinghotline.org/resources/recognizing-and-responding-human-trafficking-healthcare-context

National Human Trafficking Training and Technical Assistance Center. (2018). Toolkit: Adult human trafficking screening tool and guide. https://nhttac.acf.hhs.gov/resources/toolkit-adult-human-trafficking-screening-tool-and-guide

Office for Victims of Crime. (n.d.). Human trafficking task force e-guide. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://www.ovcttac.gov/taskforceguide/eguide/

Office on Trafficking in Persons. (2017). Fact sheet: Human trafficking. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/otip/fact-sheet/resource/fshumantrafficking

Office on Trafficking in Persons. (2019). SOAR to health and wellness training. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/otip/training/soar-health-and-wellness-training

Ottisova, L., Hemmings, S., Howard, L., Zimmerman, C., & Oram, S. (2016). Prevalence and risk of violence and the mental, physical, and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: An updated systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 25(4), 317-341. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000135

Powell, C., Dickins, K., & Stoklosa, H. (2017). Training US health care professionals on human trafficking: Where do we go from here? Medical Education Online, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2017.1267980

Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act, Pub. L. No. 113–183 (2014). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/PLAW-113publ183

Simich, L., Goyen, L., Powell, A., & Berberich, K. (2014). Out of the shadows: A tool for the identification of victims of human trafficking. Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/publications/out-of-the-shadows-identification-of-victims-of-human-trafficking

StoptheTraffik.org. (2018, September 24). Sex trafficking vs. sex work: Understanding the difference. https://www.stopthetraffik.org/sex-trafficking-vs-sex-work-understanding-difference/

Texas Family Code, Tx. Stat. § 261.101(b). (1995 & rev. 2017). https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/FA/htm/FA.261.htm

Texas Occupations Code, Tx. Stat. § 301.308 (2019). https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/OC/htm/OC.301.htm

Toney-Butler, T. J., & Mittel, O. (2020). Human trafficking. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430910/

Trafficking Victims Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 106-386 (2000). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/PLAW-106publ386

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (n.d.). What is human trafficking? Retrieved January 14, 2021, from //www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/what-is-human-trafficking.html

US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. (2017). Human trafficking vs. human smuggling. The Cornerstone Report. https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report/2017/CSReport-13-1.pdf

Wood, L. C. N. (2020). Child modern slavery, trafficking, and health: A practical review of factors contributing to children’s vulnerability and the potential impacts of severe exploitation on health. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 4(1), e000327. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000327