About this course:

The purpose of this course is to ensure that nurses understand the risk for medical errors and their impact on patient outcomes.

Course preview

The purpose of this course is to ensure that nurses understand the risk of medical errors and their impact on patient outcomes.

Upon completion of this activity, learners should be able to:

- Discuss the incidence of medical errors.

- Identify common medication errors.

- Understand the nurse’s role and responsibilities in preventing medical errors.

- Utilize root cause analysis (RCA) in the identification of medical errors.

- Explore the safety needs related to the Joint Commission's National Patient Safety Goals.

- Define a sentinel event.

- Recognize the crucial aspects of a culture of safety.

Incidence

Medical errors include events that are caused by omission, commission, planning, and/or execution of medical services. Medical errors are an enormous concern to both patients and healthcare organizations as they lead to poor patient outcomes and increase the cost of healthcare delivery. Since the landmark publication, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Healthcare System was introduced in 2000 by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), healthcare organizations have taken a deeper look at the number of medical errors occurring annually and the need to improve the quality and safe delivery of patient care (IOM, 2000). Johns Hopkins Medicine (JHM, 2016) reported that medical errors are often unrecognized, even though reported medical errors lead to more than 250,000 deaths per year in the US. JHM further suggests that medical errors are likely the third leading cause of death in the US but are under-recognized in this regard due to a lack of identification and reporting. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC’s) collection of national health statistics fails to classify medical errors as a potential cause of death on death certificates, and thus available data does not capture the significance of the problem. Notedly, doctors and nurses are not considered to be inherently bad, and medical errors should not be managed with litigation or punishment, but rather viewed as systemic problems that need to be addressed. Medical errors may be symptoms of poor coordination of care, absence or lack of the use of protocols, or unwarranted variation of practice patterns by healthcare providers without accountability (JHM, 2016).

The meta-review by Zegers et al. (2016) analyzed 60 systematic reviews from 2013 to 2015 and noted that up to 10% of hospitalized patients worldwide are victims of harm or death and up to half of the events are avoidable. Beyond the emotional and physical tolls of medical errors, the annual monetary cost is estimated between $17 and $29 billion. The costs related to medical errors include increased length of hospital stay, prescription drug costs, outpatient care, lost work, and lost productivity. Unfortunately, the most significant cost of medical errors is morbidity and mortality. Even with these staggering numbers, there is some good news. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) National Scorecard reported a downward trend in hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) between 2014 and 2016. This report examines medical errors along with adverse events such as hospital-acquired infections, falls, and pressure ulcers. Focused patient safety interventions have been credited with saving up to $7.7 billion in healthcare costs and have prevented more than 20,000 hospital deaths between 2014 and 2017 (Brady, 2020).

A survey of 2,500 American adults in 2017 notes the following:

- Almost half of the adults who perceive that an error occurred during their hospital stay brought the error to the attention of hospital staff or medical personnel,

- Most of the survey's respondents believe that healthcare providers are primarily responsible for patient safety but also recognize the role of the patient and their family in patient safety as well, and

- Medical errors are multifactorial in etiology, with up to eight factors identified as the root of the problem (Institute for Healthcare Improvement [IHI], 2017).

Considering that adults recognize the risk and understand their role in medical errors, nurses must also recognize their own role and be accountable for their actions. Nurses are crucial in maintaining a culture that fosters patient safety and have a responsibility to recognize potential opportunities to promote positive change that safeguards care. To remain accountable, they must recognize and report any medical errors or adverse events. Nurses are well-positioned to educate the entire healthcare team as well as the public on identifying risk and preventing medical errors, as well as the proper way of reporting and reconciling medical errors or near misses (IHI, 2017).

Common Medical Errors

Throughout the literature, various terminology is used and associated with adverse healthcare events and medical errors. While the following categories may overlap, they are the most common across the healthcare system:

- Diagnostic errors occur when a diagnosis is missed, wrong, or delayed and may account for up to 17% of preventable errors annually (AHRQ Patient Safety Network [AHRQ PSN], 2018a).

- Medication errors are “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the healthcare professional, patient, or consumer" (National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, 2018).

- Systems or process errors are those which involve predictable human failings that are related to poorly designed systems (AHRQ PSN, 2019e).

- Active errors are those primarily involving frontline staff members and occur at the point of contact between a human and some part of a larger system (AHRQ PSN, 2019e).

- Latent errors are referred to as “accidents waiting to happen,” and involve failures of organization or design (e.g., systems and processes), which could allow active errors to cause harm (AHRQ PSN, 2019e).

- Surgical errors encompass errors that should never occur, such as wrong-site, wrong-patient, or wrong-procedure (WSPE), and identify a serious safety problem within a healthcare system or organization. This type of error occurs as frequently as one in every 112,000 surgical procedures (AHRQ PSN, 2018b).

- Pharmacy errors can occur at multiple points, including the preparation or processing of a prescription or through patient education that may be inaccurate. This may include prescribing the wrong medication, prescribing the right medication, but the wrong dosage, failing to see harmful interactions of medications, or marketing defective or unsafe medications. Pharmacy errors are associated with workload, insufficient training, negligence in supervising pharmacy technicians, poor work environment, and overreliance on automated systems for dispensing (Woods, 2017).

- Laboratory errors can include errors that lab personnel make during procedure performance, evaluation of data, reporting results of a test or procedure, or recording the results of a test or procedure (Dawson, n.d.).

- Infection-related errors include any infection acquired during a hospital stay or due to care received during hospitalization. The CDC (2017), notes that 1 in 25 patients in the US is diagnosed with an infection associated with care received during hospitalization such as central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), or Clostridium difficile (C. diff; CDC, 2017).

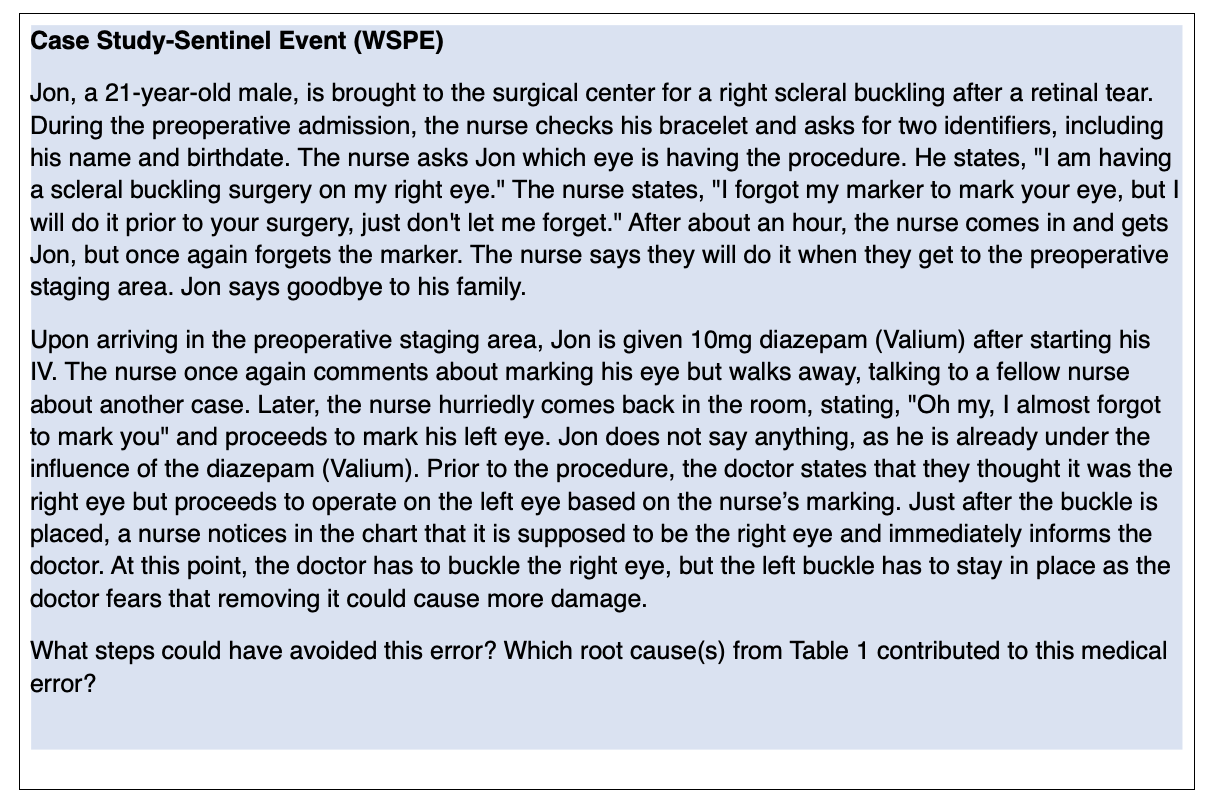

- Never events refer to shockin

...purchase below to continue the course

Additional patient safety event terminology pertinent to this topic include a no-harm event, in which there is no harm caused to the patient who encounters a patient safety event, a close call, which is a patient safety event that did not reach the patient, and a hazardous condition, which is a situation that increases the likelihood of an adverse event. These events are tracked and used as opportunities to identify problem areas within a system or process. Hospitals and other healthcare organizations use event reporting for no-harm, close call, or hazardous conditions for comprehensive analysis, risk identification, and development of a corrective action plan to avoid future occurrences (The Joint Commission [TJC], 2020).

Causative Factors

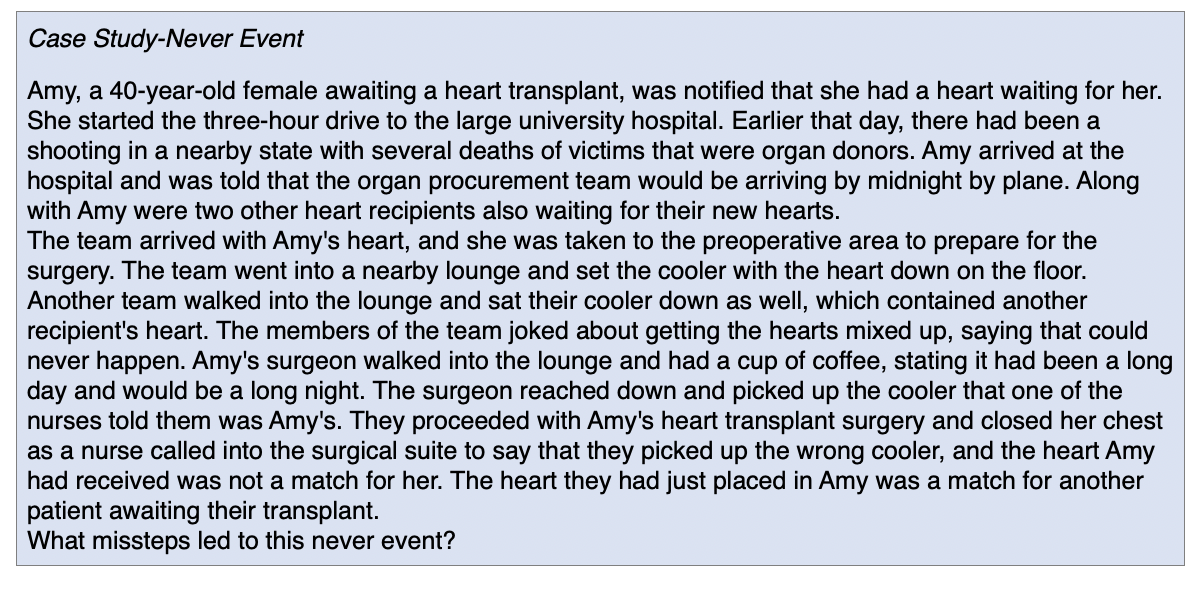

While medical errors are multifactorial, there are eight common root causes, according to AHRQ, as described in Table 1.

While various sources mention different verbiage for the cause of medical errors, almost all rank communication as the top opportunity for upholding patient safety. From diagnosis to treatment, medication administration, following policies and procedures, or patient education, nurses must effectively communicate with staff, family, and patients. The communication may be written or verbal, and errors can occur throughout the delivery of information, both by omission and commission. Failure to effectively communicate leads to medical errors and may occur at the point of patient handoff, delivery of care, or during discharge instructions. Patients or their families may be reluctant to verbalize when they do not understand instructions, or they may not seek clarification. Further, nurses may have deficient knowledge of a specific disease process or treatment and may be ineffective in the delivery of the education. Interactions between providers that lead to the mishandling of critical patient information can also be a source of communication breakdown that results in patient errors or poor outcomes. Kern (2016) notes that as many as 37% of all serious injuries between 2009 and 2013, including death, can be linked to a communication breakdown.

The TJC has several focused solutions to improve patient handoff and communication among healthcare providers and ultimately enhance processes and systems. Their Handoff Communications Targeted Solutions Tool® guides the organization through a step-by-step process to:

- Measure the organization's current handoff process,

- Identify barriers to success and provide a measurement system that creates data to support needed changes or system improvements, and

- Guide the organization to proven solutions that will address their unique needs, along with customizable forms for data collection, and guidelines for the optimum handoff communication processes (TJC Center for Transforming Healthcare [TJCCTH], n.d.a).

As previously noted, most medical errors are due to systemic or institutional failures and not from individual negligence or incompetence. Systemic failures can involve inadequate policies and procedures, failure to retain or train staff, failure to adequately staff patient care units, failure to obtain and maintain safe equipment or supplies for the delivery of care, or the failure to recognize and manage errors or the conditions that led to the errors. In today's healthcare setting, a systems approach, pioneered by British psychologist James Reason is most frequently used. His analysis of errors in industrial, aviation, and nuclear environments determined that catastrophic errors almost never occurred due to a single individual, but rather due to serious underlying flaws of the overall system. His model, called The Swiss Cheese model, describes workplaces or systems that have underlying flaws or "holes". Errors made by an individual within the system result in serious consequences due to these holes. Dr. Reason's model explains how the disasters can happen and result in a significant impact on the organization. He also describes how these holes can be identified and shrunk so they are not open to fall through again in the future. His work acknowledges that human error is inevitable, particularly in the fast-paced environment of healthcare. A systems approach can allow for the recognition of errors prior to the development of the resulting consequences. Dr. Reason uses the terms latent errors and active errors. The active error occurs at the point of contact between a human and some component of the larger system, such as a piece of equipment or department. A latent error is an accident that is waiting to happen and is usually related to a design failure of an organization that leads to inevitable harm of the patient. Other terminologies related to systemic errors include sharp end and blunt end, which align with active errors and latent errors. Personnel at the sharp end are active in the delivery of the error, such as administering the wrong medication. The blunt end refers to the layers of the healthcare system that are behind the scenes and not in direct contact with patients, but still influence the sharp end (AHRQ PSN, 2019e).

Sentinel Events

Sentinel events are "not related to the natural course of the patient's illness or underlying condition and result in death, permanent harm, or severe, temporary harm" (TJC, 2020a, para. 2). The following are considered sentinel events:

- The suicide of any patient receiving care or within 72 hours of discharge from the hospital, including the ED;

- The unanticipated death of a full-term infant;

- An infant discharged with the wrong family;

- The abduction of any patient that is receiving care, treatment, or services;

- The unauthorized departure of a patient from a staffed facility that leads to death, temporary harm, or permanent harm;

- The administration of blood or blood products that have ABO and non-ABO incompatibilities, hemolytic transfusion reactions, or transfusions resulting in temporary or permanent harm, or death;

- The rape, assault, or homicide of any patient that is receiving care, treatment or services while in the hospital or clinical setting;

- A WSPE surgery or invasive procedure;

- The unintended retention of a foreign object after an invasive procedure or surgery;

- A case of severe neonatal hyperbilirubinemia (bilirubin level greater than 30 mg/dL);

- The prolonged use of fluoroscopy, with a cumulative dose greater than 1,500 rads to a single field or delivery of radiotherapy to the wrong body region;

- The presence of fire, flame, or unintended smoke, heat, or flashes during direct patient care caused by equipment operated or used by the hospital and in use during the time of the event whether staff is present or not;

- An intrapartum maternal death;

- An instance of severe maternal morbidity that reaches a patient and results in permanent harm or severe, temporary harm (TJC, 2020b).

These significant events are grave patient safety issues and signal the need for an immediate response by the organization to protect patient safety. Sentinel events can be related to patient acuity, staff dependence on medical technology, pressure to reduce lengths of stay, and the shortage of nurses or other healthcare workers. Hospitals frequently find a breakdown in communication across disciplines regarding a patient's plan of care as the leading cause of sentinel events. Most sentinel events are the result of a systems-related problem with several root causes and not the mistake of a single individual (TJC, 2020b).

The TJC requires all accredited hospitals to define sentinel events for their institution. The definition is expected to be communicated to all departments within the facility and services associated with the institution. Reporting of a sentinel event by the hospital to the TJC is voluntary. The TJC also learns about the occurrence of sentinel events through complaint avenues. When a sentinel event is identified, the hospital is expected to respond by stabilizing the patient, communicating with the patient and family concerning the event, notifying the hospital leadership, investigating the incidence, completing a route cause analysis, developing a corrective action plan with a timeline for implementation, and showing improvement (TJC, 2020b).

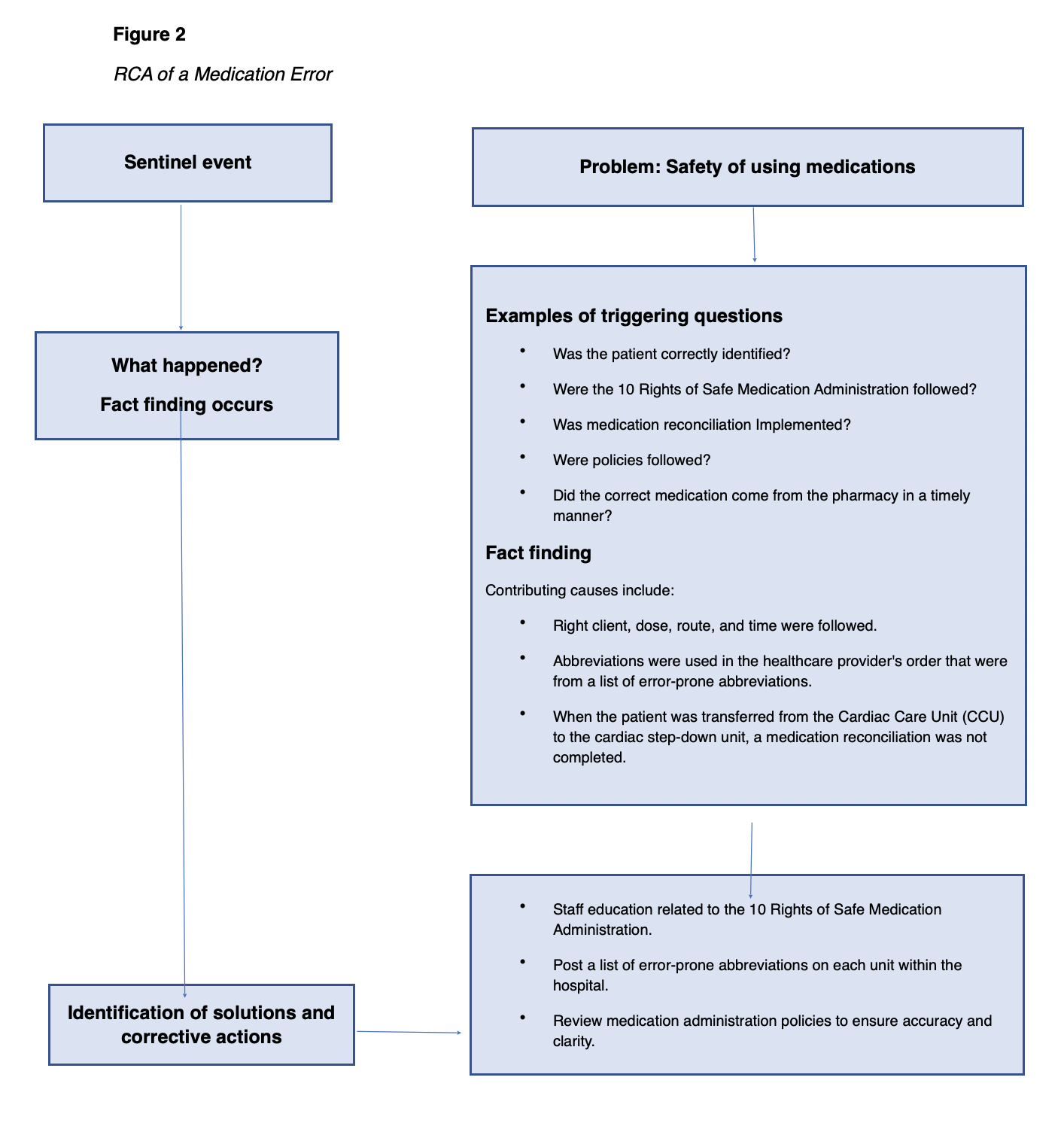

Root Cause Analysis

Root cause analysis (RCA) is the method for analyzing medical errors to accurately identify safety improvement measures. The root cause is a problem or factor that, when eliminated in a sequence of problems or faults, prevents the adverse event from occurring. This is often not the factor identified at the initial examination. The TJC publishes a Framework for RCA and Action Plan in order to provide an example of a comprehensive systematic analysis for healthcare organizations. The framework outlines the steps and information needed in an RCA of an event for quality improvement. Since 1997, TJC has mandated that sentinel events be analyzed using RCA, and 27 states mandate reporting of such events. In 2015, the renamed Root Cause Analyses and Actions (RCA2) was introduced to improve the effectiveness of the original tool with a focus on preventing future harm (IHI, 2015).

The focus of the RCA2 review is to determine system vulnerabilities so they can be mitigated and ultimately eliminated. An RCA2 focuses on the underlying cause of an event and not the individual. A predetermined systematic procedure is initiated to collect information and reconstruct the event by questioning the individuals involved, reviewing the records, and analyzing the reason why the event occurred (IHI, 2015).

The primary aim of RCA2 is to identify the factors that resulted in the negative outcomes of one or more past events to identify what needs to be changed to prevent future events. RCA2 is performed systematically by a team as part of an investigation, with conclusions and root cause(s) supported by documented evidence. There may be more than one root cause for an event or a problem. All possible solutions to a problem are identified to prevent future events at the lowest possible cost and in the simplest possible way. The RCA2 should determine a sequence of events or a timeline to understand the relationships between the root cause(s) and the event to prevent it from happening in the future. Root cause analysis is designed to reduce the frequency of undesirable events that occur over time within the environment where the RCA2 process is used. RCA2 is based on the 5 “whys” or the Five Rules of Causation (asking why five times to get to the real root of a problem). Asking these whys will lead to causal statements which are written to describe the cause, effect, and event. Example: something (cause) leads to something (effect), which increases the likelihood the adverse of something (event) will occur (National Patient Safety Foundation [NPSF], 2016).

To reduce the incidence of medical errors, their causes must be correctly identified, plans developed to improve processes that reduce the risk, along with methods to measure the successes and failures of interventions. The assessment of the problem must be based on clear and consistent definitions in order to be useful in reducing the incidence of sentinel events. Data collection and subsequent solutions for eliminating related errors are hindered by differing definitions that reflect the variety of purposes for which data is collected and used. Examples include research, insurance, legal actions, lawmaking, ethics, and quality control. The varied terminology used to describe errors may result in difficulty comparing error rates in the published literature. Adding near misses into the discussion further complicates the issue but should not be overlooked as this focus could add to the data on the prevention of errors and quality improvement (NPSF, 2016).

National Patient Safety Goals and a Culture of Safety

TJCs National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG) were designed to improve patient safety by focusing on specific problems and how to solve them. The NPSGs were updated in 2020 (TJC, 2020a). There are separate chapters with individualized goals for each area of practice for healthcare providers to follow, including the following:

- Ambulatory Healthcare Chapter,

- Behavioral Healthcare Chapter,

- Critical Access Hospital Chapter,

- Home Care Chapter,

- Hospital Chapter,

- Laboratory Chapter,

- Nursing Care Center Chapter, and

- Office-Based Surgery Chapter (TJC, 2020a).

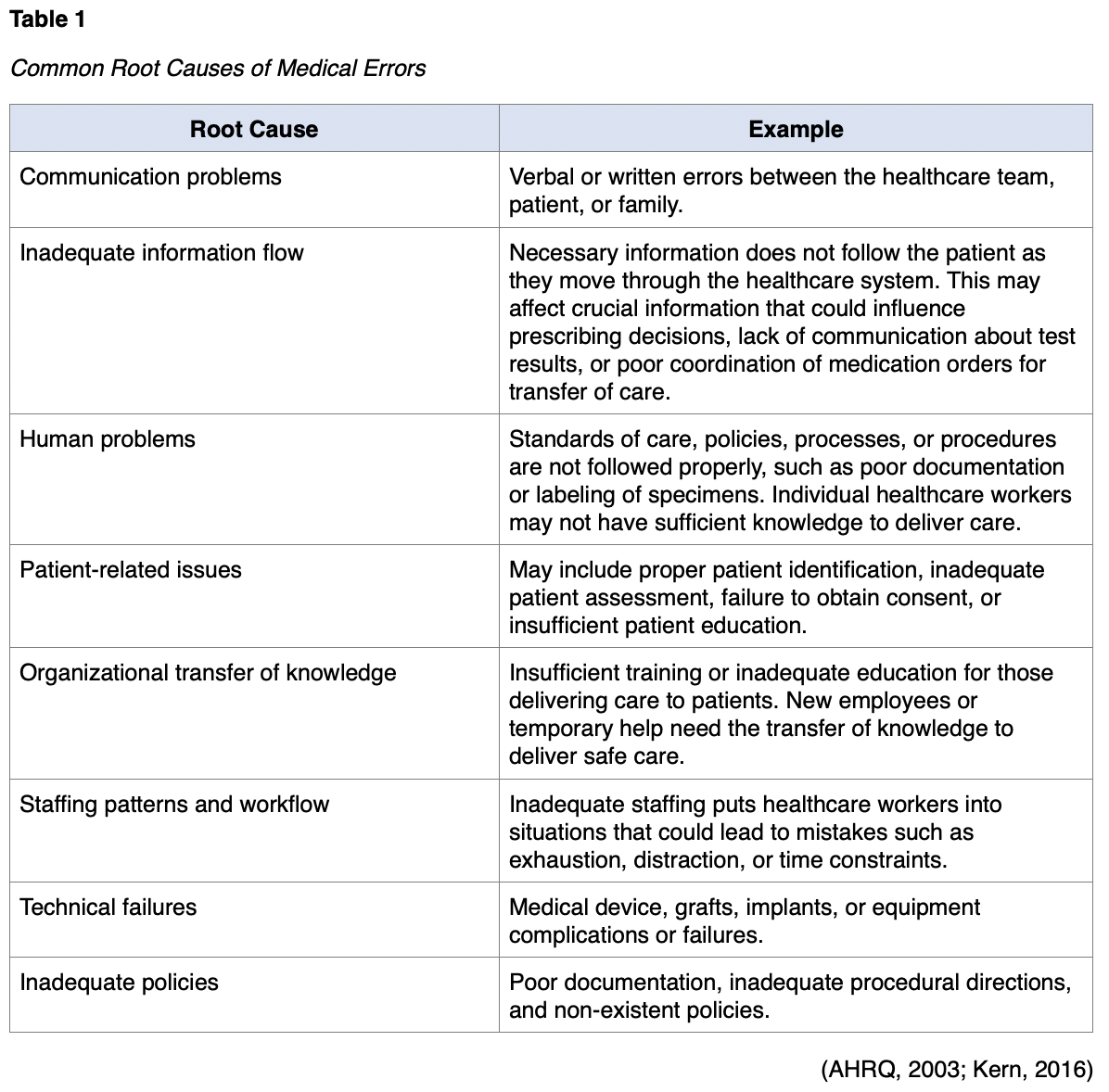

See Table 2 for the NPSGs for hospital programs.

The TJC reviews the NPSGs each year as data is collected regarding emerging patient safety concerns. The goals are tailored to address the most urgent concerns occurring in the healthcare setting each year (TJC, 2020a). The current NPSGs can be accessed via the TJC website.

Vital to a safe environment for staff and patients is the fostering of a "culture of safety." The AHRQ defines a culture of safety as one that encompasses the following features:

- Recognition that a healthcare organization is high-risk and has an obligation to consistently operate in a safe manner;

- A blame-free environment where everyone is free to report errors and near misses without the fear of punishment or reprimand;

- Collaboration and encouragement of all disciplines to seek solutions for patient safety concerns;

- An organizational commitment to allocate resources to address safety concerns (AHRQ PSN, 2019b).

Having a blame-free environment to identify areas of concern that may contribute to patient safety is crucial to ensuring providers at all levels understand the organizational commitment to establishing a safety culture. If a culture of "low expectations" exists, poor teamwork and communication can lead to an underdeveloped safety culture. The institution’s culture can be evaluated through surveys such as the AHRQs Patient Safety Cultures Survey or the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire. These surveys ask providers to rate their current culture of safety within individual units as well as the overall organization. When an organization is found to have a poor culture of safety based on the surveys, there are specific measures that can be taken to make improvements; yet sustained improvements can be difficult to achieve. The following measures are associated with improvements:

- Teamwork training,

- Executive walking rounds,

- Unit-based safety teams,

- Rapid-response teams, and

- Structured communication tools, such as SBAR (AHRQ PSN, 2019b).

When a culture of safety is centered around the ability to report errors and near misses, the complete removal of blame or accountability is difficult. There are errors that demand accountability; thus, a newer term, just culture, is often used instead. A just culture still focuses on the systemic problems that lead to errors; however, individual accountability for reckless behavior such as ignoring policies, skipping safety steps, or improper implementation of plans of care is also applied. An example may be a specific surgeon proceeding with a surgical procedure without the time-out process and performing surgery on the wrong limb. The facility had a policy in place to provide safety, but it was not followed consistently. Even if a patient is not harmed, this behavior is noteworthy and should be addressed with the surgeon. In an article by Lockhart (2017), a just culture is characterized as demanding accountability and quality through improved processes and systems within the workplace. Employees should not be afraid to report errors in a just culture, and if correctly implemented, staff and patient satisfaction are increased, and safety is ensured. Effective communication, management of resources, and process development that focuses on the safety of both patients and hospital staff can ensure success in the development of a just culture (Lockhart, 2017).

The Partnership for Patients Campaign

In 2011, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) Innovation Center initiated the Partnership for Patients (PfP) campaign, which focused on a list of significant patient concerns and areas of harm. The campaign originated from patient safety concerns that began with the IOM's 2000 report, and the goal is to spread best practices that will enhance patient safety to all US hospitals. Harm areas of focus for PfP are:

- Adverse drug events (ADE),

- CAUTI,

- CLABSI,

- Fall and immobility injuries,

- Perinatal/obstetrical (OB),

- Pressure ulcers,

- Preventable readmissions,

- Surgical site infections (SSIs),

- Venous thromboembolism (VTE), and

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) (CMS, 2020).

The goals of the campaign are to save lives, decrease harm, and reduce costs for the CMS programs. By 2014, the program published a report that an estimated 50,000 fewer patients had died in hospitals, and up to $12 billion healthcare dollars had been saved from the resulting reduction of hospital-acquired conditions from 2010-2013. This accounted for a 17% reduction in hospital-acquired conditions over the three-year period in comparison to 2006-2009 (CMS, 2020). While the program concluded at the end of 2014, the standards of care and focused areas continue with NPSGs and the AHRQ National Scorecard on Hospital-Acquired Conditions (2019). A closer look at each focus can provide opportunities to avoid medical errors for nurses.

Medication Errors (ADEs)

The AHRQ PSN (2019b) defined a medication error or ADE as "harm experienced by a patient as the result of exposure to a medication" (para. 1). In a more general term, an ADE does not indicate harm necessarily. ADEs that do not cause harm to the patient is called potential ADEs. Preventable ADEs harm the patient (to any degree) due to an ADE that reached the patient but could have been avoided. About half of ADEs are preventable with proper caution. Ameliorable ADEs are those which resulted in patient harm and may have been mitigated with proper steps in place, although not completely preventable. Finally, there are nonpreventable ADEs that patients may experience even with proper prescribing and administration. These are most commonly known as side effects or adverse effects. It is estimated that 5% of hospitalized patients experience an ADE, making them the most common type of inpatient medical error. Patients outside the hospital also experience ADEs at even higher rates, including an increase in deaths annually due to opioid medications. Annually over 700,000 emergency department (ED) visits occur due to ADEs and a resultant 100,000 hospitalizations. Healthcare practitioners have access to over 10,000 prescription medications to offer patients as part of their plan of treatment, and more than one-third of American adults take five or more medications daily. There is ample opportunity for poor outcomes even if the medications are taken precisely as ordered. There are specific patient, drug, and clinician risk factors for ADEs. The highest risk for ADE is polypharmacy, or the use of more medications than necessary to manage health conditions. Geriatric patients are more vulnerable to adverse reactions than younger patients, and they often take several medications for various conditions. Pediatric patients are also at a higher risk for ADEs and should be dosed according to weight rather than age. Other patient-specific risks lie with health literacy and the ability to use basic math operations for daily tasks. In the community setting, parents, patients, and caregivers often commit ADEs at high rates due to the inability to understand the directions for administration (AHRQ PSN, 2019c).

A list of high-alert medications that can cause significant patient harm if used in error was published by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP, 2018). It includes medications with dangerous adverse effects, look-alike/sound-alike (LASA) names, or similar names or physical appearance but very different pharmaceutical properties. The ISMPs List of Confused Drug Names can be helpful for nurses to avoid common opportunities for error by listing LASA name pairs. Among the list is diazepam (Valium), which is often confused with diltiazem (Cardizem), dextroamphetamine (Adderall) versus propranolol (Inderal), or hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) versus hydroxyzine (Vistaril). Considering the drastic differences within these examples, it is evident how quickly a patient could have adverse reactions with the wrong medication administered (ISMP, 2019). High-alert medications that are recognized by the ISMP have a higher risk for significant patient harm if administered in error and include:

- Epinephrine, both IM and subcutaneous;

- Epoprostenol (Flolan), IV;

- All insulins are considered high-alert medications, but especially insulin U-500 due to its concentrated form;

- Magnesium sulfate, IV;

- Methotrexate (Rheumatrex), oral, nononcologic use;

- Opium tincture (Pantopon), oral;

- Oxytocin (Pitocin), IV;

- Nitroprusside sodium (Nipride, Nitropress), IV;

- Potassium chloride for injection concentrate;

- Potassium phosphates injection;

- Promethazine (Phenergan), IV;

- Vasopressin (Vasostrict), IV, or intraosseous (ISMP, 2018).

While discussing ADEs, the opioid crisis should be addressed. Nurses will likely see patients entering the clinical setting that are using opioids. There are many questions related to the appropriate use of these medications for pain relief. Nurses should be aware of the potential for abuse by patients and how these drugs may affect other medications that are being administered concurrently. Opioid administration can lead to allergic reaction, over-sedation, respiratory depression, seizure, or death. Several practices can decrease the risk of adverse reaction or interactions due to opioid use in hospitals, including:

- Label the distal end of all IV lines to distinguish between epidural and IV lines.

- Have mandatory double-checks of the patient and medication order when setting up opioid infusions or pumps.

- Establish guidelines for appropriate monitoring of patients who are receiving opioids and monitor for over-sedation in addition to respiratory rate.

- Avoid reliance on pulse-oximeter readings alone to detect toxicity. Capnography should be utilized to detect respiratory changes, particularly with high-risk patients such as those with obesity or sleep apnea.

- Have oxygen and naloxone (Narcan) readily available if needed when administering opioids.

- Prepare protocols for administering reversal agents that can be administered without obtaining stat orders.

- Educate patients and their caregivers/family members in relation to patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps and follow established monitoring and observation of the patient receiving the medication.

- Establish an agreed-upon pain score goal prior to administration, then administer opioids with this goal in mind to avoid over-sedation.

- Educate patients who are prescribed fentanyl (Duragesic) patches on proper use and disposal (ISMP, 2017).

For more information on the nurse’s role in opioid use refer to the NursingCE course on opioids.

ADEs may be rule-based, memory-based, knowledge-based, or action-based (Ambwani et al., 2019).

Rule-based errors occur when nurses use a bad rule, or they misapply a good rule. An example of failure to apply a good rule would be a nurse who hangs a bag of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) without cross-checking the ingredients with the current physician's order and asking a second nurse to perform a double-check. The application of a bad rule might be a facility that does not have a policy that requires double-checks of the TPN prior to patient administration. Either situation could result in a poor patient outcome. This type of error can be avoided through proper training and education, as well as the consistent implementation of existing rules by nurses and others (Ambwani et al., 2019).

Memory-based errors are lapses in memory by nurses. An example would be a nurse who administers penicillin (PCN) to a patient whom they know has an allergy to PCN but simply forgot. This type of error can be avoided with computerized prescribing systems and cross-checking allergies with each administration of medications (Ambwani et al., 2019).

Knowledge-based errors occur when nurses are missing information. An example is administering PCN to a patient without establishing if they have an allergy first. This type of error can be avoided through appropriate intake of information on admission, and computerized prescribing systems that track the patient's information so that pharmacists, healthcare providers, and nurses are able to cross-check each other (Ambwani et al., 2019).

Action-based errors or "slips" are primarily due to carelessness during routine prescribing, dispensing, or administering medications. Examples are a pharmacist adding the wrong amount of potassium chloride into an IV bag due to distractions; a nurse who pulls 5 mg of a medication rather than 0.5 mg into a syringe because they were rushed as they were drawing up the medication; or a nurse who overrides the electronic dispensing system to pull up a medication believing it to be required, not realizing that the physician had discontinued it earlier. This type of error can be avoided by minimizing distractions, cross-checking orders with a second nurse, following the ten rights of medication administration, or the using bar codes (Ambwani et al., 2019).

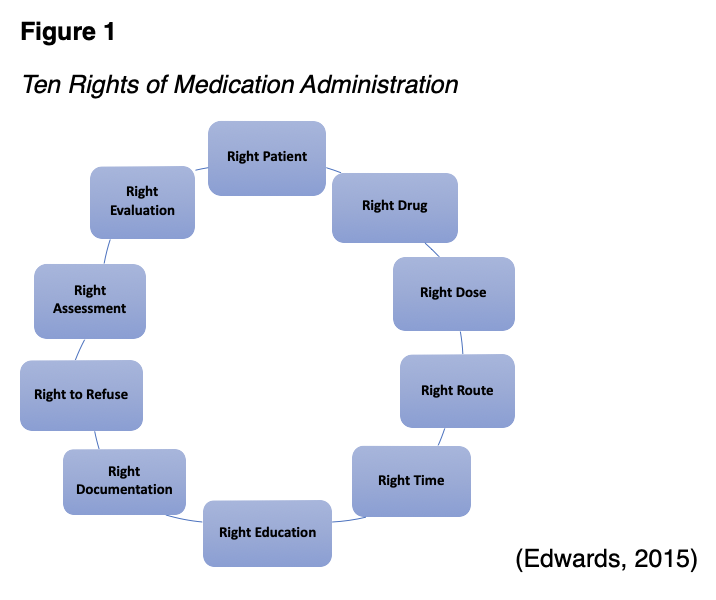

Nurses can avoid medication errors using the rights of medication administration. Various sources refer to the five rights of medication administration, and some list up to ten rights of medication administration. While errors can occur from the time the healthcare provider writes the prescription, to the pharmacy filling the order, to the actual delivery of medication to the patient, nurses have the opportunity to recognize concerns at every step of the way by using this systematic approach to medication administration (Edwards, 2015). See Figure 1 for the ten rights of medication administration.

Regardless of the number of rights, nurses must ensure safe medication administration. Mistakes can take place at various steps in the medication administration process but following the steps consistently can reduce or avoid costly errors (Edwards, 2015).

In addition to the ten rights, nurses should ensure that handoffs are thorough, and that essential information has been communicated to the oncoming nurse. Bar code and scanning technology along with electronic health records with computerized prescriber order entry can reduce medication errors when used properly. The appropriate medication, route, dose, and duration should be selected; the entire interdisciplinary team is responsible for promoting safe medication administration (AHRQ PSN, 2019c).

There are three specific medication safety issues identified by the NPSGs: labeling of medications, anticoagulant therapy, and medication reconciliation (TJC, 2020a).

The way medications are labeled and packaged can lead to medication errors. Labels may cause confusion leading to errors when the following situations occur: (a) marketing distractions, (b) labels or drug names look alike, (c) drug names are the same, but the drugs have different purposes, (d) information on the label may be difficult to find, and (e) warning information may be hidden. A manufacturer may want to draw attention to its product by using eye-catching adjectives or phrases, distracting the consumer. Drugs may come in different forms (i.e., capsules, gel tabs) and in different strengths; however, the drug companies often package them in containers that look alike. When a drug company has a well-known brand name for one product, they may introduce a new product under the same name; yet the two products may treat different medical conditions (i.e., a stool softener vs. a laxative). Important information about a drug may not be readily accessible, as it can be located underneath the label. The label reads "peel back" causing individuals not to notice the instructions or to think they cannot peel back the label without buying the drug. Finally, warning information regarding a drug, such as allergic ingredients, might be in a less obvious place on the medication container leading individuals to miss this information (Edwards 2015).

Anticoagulant drugs (i.e., dabigatran [Pradaxa], rivaroxaban [Xarelto], apixaban [Eliquis] and warfarin [Coumadin]) are widely used for both the treatment and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism; they most frequently cause adverse medication incidents in hospitals, especially during admission, discharge, and surgery. Studies have shown that prescribing excess anticoagulant was the most frequent problem during admission and surgery, and prescribing insufficient anticoagulant was the most frequent problem during discharge. Management of anticoagulant therapy involves awareness of the difference between bleeding caused by over-dosing and clotting caused by under-dosing, as both conditions can be fatal. Further, some anticoagulation medications have reversal agents such as warfarin (Coumadin) and dabigatran (Pradaxa) while some have no reversal such as rivaroxaban (Xarelto) or apixaban (Eliquis) (Henriksen et al., 2017).

For further information on anticoagulation medications and the reversal agents, see the NursingCE module on Bleeding and Clotting.

Medication reconciliation is the process of creating an accurate list of all medications a patient is taking to avoid errors. The medication list needs to include the drug name, dosage, frequency, and route. To ensure the correct medications are administered, the medication list needs to be compared to the physician's orders at the time of admission, when transferred from one hospital unit to another, and at the time of discharge. Potential errors during medication reconciliation are omitting a medication, recording the medication more than once, or recording an incorrect dose/frequency (IHI, n.d).

Any of the above medication errors can lead to a sentinel event causing the healthcare organization to implement an RCA to determine the cause(s). Figure 2 depicts an example of an RCA such as the TJC Sentinel Event Alert #61 for the safety of using oral anticoagulants (TJC, n.d.c).

Prevention of Medication Errors

Medications are chemicals that affect the body, and every medication has the potential to cause adverse effects. These are undesired, inadvertent, and harmful effects of the medication. Adverse effects can range from mild to severe, and some can be life‑threatening. There is a potential for interactions with concurrent medications as well as foods and dietary supplements. Contraindications and precautions for specific medications are conditions (diseases, age, pregnancy, lactation) that make it risky or completely unsafe for patients to take them.

The nurse's responsibilities to prevent medication errors include:

- Having knowledge of federal, state (nurse practice acts), and local laws, and facilities' policies that govern the prescribing, dispensing, and administration of medications;

- Preparing, administering, and evaluating the patients’ responses to medications;

- Developing and maintaining an up‑to‑date knowledge base of medications they administer regularly, including uses, mechanisms of action, routes of administration, safe dosage range, adverse and side effects, precautions, contraindications, and interactions;

- Maintaining knowledge of acceptable practice and skills competency;

- Determining the accuracy of medication prescriptions;

- Reporting all medication errors;

- Safeguarding and storing medications (Burchum & Rosenthal, 2019).

The anticipation of side effects, interactions, contraindications, and precautions is an important component of patient education. Both the nurse and the patient should know the major adverse effects a medication can cause. Early identification of adverse effects allows for timely intervention to minimize harm (Burcham & Rosenthal, 2019).

Healthcare Associated Infections (HAIs)

HAIs are significant causes of infections within all types of healthcare institutions. They are the most common complication of hospital care. An HAI is an infection contracted while receiving treatment for another medical or surgical condition. These infections are associated with increased healthcare costs, extended hospital stays, medical complications, and patient deaths. Several organizations, such as the CDC and TJC, have made significant progress in preventing specific HAIs. In addition to CAUTI and CLABSI are SSIs and multidrug-resistant organisms (The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], 2020). Bacteria most commonly cause infections following surgery. Bacteria can infect a surgical site through a contaminated caregiver, surgical instruments, and/or bacteria already on the patient's body. The CDC has identified three types of surgical site infections:

- Superficial incisional infection, which occurs just in the area of the incision;

- Deep incisional infection, which occurs in the muscle and the tissues surrounding the muscle beneath the incision;

- Organ infection, which occurs in any area of the body, a body organ, or a space between organs (Berrios-Torres et al., 2017).

Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) are bacteria or other organisms that are resistant to more than one antibiotic. MDROs make certain HAIs more difficult to treat. This phenomenon occurs when an individual takes an antibiotic for a long time or when an individual takes an antibiotic that is not necessary. MDROs can spread by hand contact or contact with contaminated equipment or surfaces. Infections occur most frequently in older patients, those with a compromised immune system, a history of repeated hospitalizations, or recent surgery. Although treatment with antibiotics is difficult, once the type of MDRO is identified, specific antibiotics the bacteria are sensitive to can be used (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 2017).

CAUTI

Up to 25% of all patients admitted to the hospital receive urinary catheters during their stay. A startling 90% of patients in the critical care setting have a urinary catheter during their hospitalization, whether indicated or not. Approximately 75% of urinary tract infections (UTIs) are associated with a urinary catheter. The most crucial factor in a patient developing a CAUTI is the use of a urinary catheter. Thus, urinary catheters should only be used when necessary and for the shortest time possible to avoid complications (CDC, 2015a). The recommendations to prevent CAUTIs are:

- Institutions should develop policies and procedures for catheter use that include indications for their use, guidelines for insertion, and criteria for length of use.

- Institutions have the responsibility to ensure that nurses are trained and competent in urinary catheter insertion and maintenance.

- The nurse should ensure that supplies and equipment are readily available for aseptic catheterization technique.

- The healthcare team should review the need for catheters daily and remove them as soon as possible.

- Institutions should develop infection control surveillance programs that include monitoring for CAUTIs, action plans for CAUTI occurrence, and staff training on the action plan (CDC, 2019a).

CLABSI

Annually, there are over 250,000 cases of CLABSI in the US, with around 80,000 occurring in intensive care units (ICUs). Each infection is estimated to cost around $46,000, running the economic impact into the billions of dollars. Even if the financial impact is not considered, the patient's personal impact is significant. CLABSIs can lead to serious morbidity and mortality, with thousands of deaths occurring each year due to CLABSI. The CDC (2011, 2015b) identifies steps for healthcare providers to prevent these infections. The following practices are recommended to avoid CLABSI in hospitalized patients requiring central lines:

- Good hand hygiene should be performed before placing a central venous catheter (CVC), as well as before and after palpating the catheter insertion site and before and after replacing, accessing, repairing, or dressing a CVC or tubing. Anyone touching the line should wash their hands before and after touching the line with soap and water or an alcohol-based hand cleaner.

- Skin antiseptic such as 0.5% chlorhexidine with alcohol should be applied over the area of insertion. If chlorhexidine is contraindicated, 70% alcohol, tincture of iodine, or an iodophor can be used. The skin prep agent should be dry before inserting the CVC.

- The five maximal sterile barrier precautions should be utilized: sterile gloves, sterile gown, cap, mask, and a large sterile drape.

- Site selection is important to decrease the risk of infection, and the CDC recommends avoiding the femoral vein for central venous access in adults. The subclavian is preferred to the jugular for a non-tunneled CVC placement but should be avoided in patients receiving dialysis due to the risk of subclavian vein stenosis.

- When a central line is in place, policies related to dressing changes or tubing changes should be followed meticulously. Dressings should consist of either sterile gauze or sterile occlusive dressings. Topical antibiotics or creams should be avoided to decrease the risk of fungal infections or antimicrobial resistance. Dressings should be changed every two days for gauze dressings and every seven days for occlusive dressings.

- A central line should be removed as soon as it is no longer needed to decrease the risk of infection.

- The nurse should provide the following patient education:

- Avoid getting the central line or area around the catheter wet.

- Report any concerns with the bandage, such as loosening around the edges or coming off.

- Report if the area around the catheter insertion site becomes red, warm, or sore and report if they have chills or fever.

- Patients, families, or visitors should not touch the line or tubing.

- Anyone entering the room must wash their hands before entering and upon leaving (CDC, 2011, 2015b).

Any of the above HAIs can lead to a sentinel event causing the healthcare organization to implement an RCA to determine the cause(s). Figure 3 depicts an RCA identified by the TJC Sentinel Event Alert #28 for decreasing HAIs (TJC, n.d.a).

Prevention of HAIs

One of the most important ways to prevent HAIs is diligent hand hygiene by all healthcare providers regardless of the healthcare setting. The NPSGs require compliance with either the CDC or the WHO hand hygiene guidelines (TJC, 2020b).

For pathogens to be transmitted from one patient to another via the hands of the healthcare worker, the following chain of events must occur:

- The organism must be present on the patient's skin, and the hands of the healthcare worker must come in contact with the organism.

- The organism must be able to survive for several minutes on the hands of the healthcare worker.

- Handwashing by the healthcare worker must be inadequate or omitted, or the type of cleansing agent unsuitable.

- The contaminated hands of the healthcare worker must come in contact with another patient (CDC, 2020).

Hand hygiene applies to handwashing with soap and water, alcohol-based hand sanitizer, or surgical hand antisepsis. Soaps (non-antimicrobial agents) are considered suitable for routine cleansing and removal of most transient microorganisms. When the risk for infection is high, alcohol-based hand sanitizers (antimicrobial agents) more effectively reduce bacteria. When the healthcare worker's hands are minimally soiled, alcohol-based hand sanitizers are considered suitable to use. If the healthcare worker's hands are visibly soiled, particularly with body fluids, soap and water should be used for handwashing (CDC, 2020).

Injuries Related to Falls and Immobility

The American Nurses Association’s Magnet Recognition program and the NPSGs for 2020 include falls as one of the core indicators of performance. Hospitals have devoted quality improvement and research efforts to prevent falls, but patient falls continually constitute the largest single category of self-reported adverse events in acute care facilities. Falls resulting in injury are a significant patient safety problem. Although elderly and frail patients are known fall risks, it is important to recognize that medical conditions, medications, as well as surgical, medical, and diagnostic procedures can cause patients of any age or physical ability to be at risk for a fall (Massachusetts General Hospital, 2017). The AHRQ (2018) reports an estimated 700,000 to 1,000,000 falls in US hospitals each year, with about 11,000 resulting in death. Injuries range from bruises and soft tissue injuries and fractures to serious traumatic brain injuries. The cost per patient for each injury is just over $14,000, running into the billions of dollars each year for direct and indirect costs. Direct costs include hospital and nursing home fees, doctors, therapists, nurses, medical equipment, and prescription drugs. Indirect costs are disability, loss of income, and poor quality of life (Florence et al., 2018). The TJCCTH project identified several factors associated with the risk of falls, including:

- Risk assessment tools are not valid predictors of actual fall risk.

- Ratings on fall risk assessment tools are often inconsistent among caregivers.

- Communication among caregivers related to patient fall risk is typically inadequate or inconsistent.

- Patients do not ask for help when toileting.

- Patients do not use their call light for help.

- There is a lack of standardization with practice and interventions to decrease fall risk.

- There is a lack of consistent education for patients and families related to falls.

- The risk of falls is increased for patients on one or more medications such as sedatives, laxatives, diuretics, narcotics, antipsychotics, or antihypertensives (TJCCTH, n.d.b).

The ECRI Institute, a non-profit agency that conducts evidence-based research, reports a significant number of falls in non-hospital settings such as long-term care facilities. Organizations also conduct community fall prevention campaigns due to the high risk of falls resulting in injury in older adults (TJC, 2015). The National Council on Aging (NCOA, n.d.) has identified the following as factors contributing to the susceptibility of older adults to falls and injury.

- As we age, most of us lose some coordination, flexibility, and balance, primarily through inactivity, making it easier to fall.

- In the aging eye, less light reaches the retina, making contrasting edges, tripping hazards, and obstacles harder to see.

- Some prescriptions and over-the-counter medications can cause dizziness, dehydration, or interactions with each other, leading to a fall.

- Most seniors have lived in their homes for a long time and have never thought about simple modifications that might keep them safer.

- More than 80% of older adults have at least one chronic condition like diabetes, stroke, or arthritis. These often increase the risk of falling due to lost function, inactivity, depression, pain, or multiple medications (NCOA, n.d.).

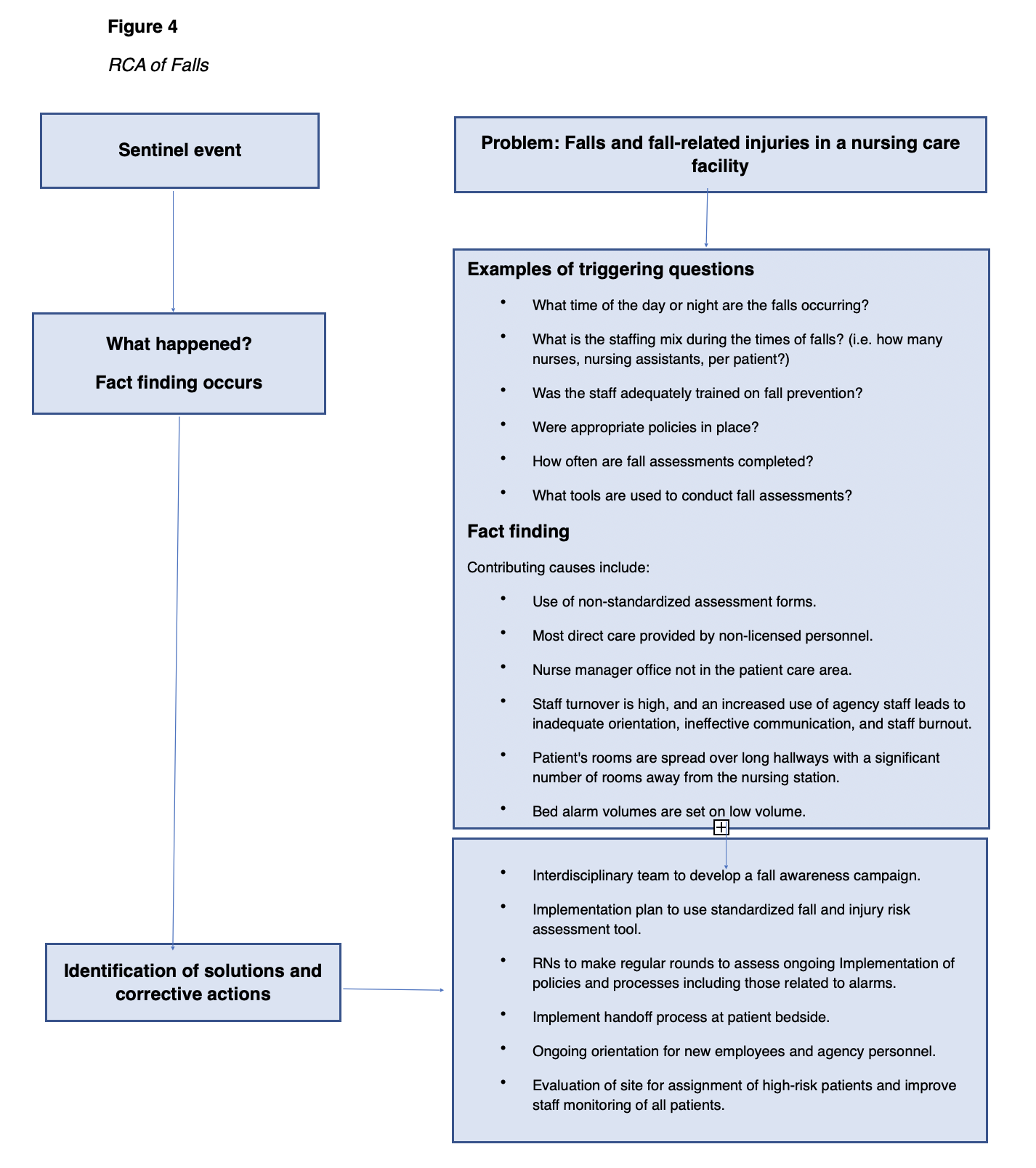

Finally, the entire culture must be focused on fall prevention and safety, which includes understanding and decreasing the risks to avoid falls or pressure injuries (AHRQ, 2014). See Figure 4 for an RCA of falls.

Prevention of Falls

Based on the findings from the TJCCTH project, the following suggestions are given to prevent falls and decrease fall risk:

- Develop a culture of safety that is supported by leadership and all healthcare workers.

- Develop standardized policies and procedures that promote fall prevention consistently.

- Implement protocols that manage extra precautions for those with cognitive problems.

- Educate patients and their families on the use of call lights, the patient's risk for falls, and to avoid getting out of bed without assistance.

- Educate patients and their families on the side effects of their medications and particularly any increased risk of falls.

- Avoid blaming Individuals for falls when they occur. If a fall occurs, obtain a post-fall evaluation to identify the contributing factors that led to the fall and eliminate future risks (TJCCTH, n.d.b).

Targeted solutions are suggested for fall risks. For example, if a patient falls or is at risk of falling while toileting, the staff should perform hourly rounding to proactively toilet the patient and avoid unassisted ambulation. For medications that put the patient at risk of falls, there should be targeted education on the medication's side effects and the increased risk of falling along with scheduling the medication administration at least two hours before bedtime. Elderly patients should develop a fall prevention action plan with their family that includes a review of their risk factors and a plan to minimize risk. Public education campaigns regarding the reduction of fall risks at home (i.e., throw rugs, clear lighting in pathways/walkways, etc) may allow the nurse to extend fall prevention efforts beyond the healthcare setting as well (TJCCTH, n.d.b; NCOA, n.d.).

Prevention of Immobility-related Injuries

Pressure injuries are of great concern to hospitalized patients, particularly those with limited mobility or on bed rest and those in long-term care facilities or home care. The AHRQ's (2014) suggested best practices for pressure ulcer prevention include the following:

- Comprehensive skin assessment,

- Standardized pressure ulcer risk assessment, and

- Care planning and implementation to address areas of risk.

A comprehensive skin assessment should focus on skin temperature, color, moisture, turgor, and integrity. If any disruption of the skin is found, it should be identified, assessed, and documented thoroughly. A verified tool such as the Braden Scale or Norton Scale should be used consistently among nurses. The tool recognizes risk for pressure ulcers and allows for ongoing, consistent assessment for risk or actual injury. Risk assessment should be repeated s indicated. The risk assessment should be performed every shift in acute care, weekly for four weeks then quarterly in long-term care facilities, and with every visit with a home care nurse. Staff should use the same tool consistently for all assessments. The plan of care should be developed with specific patient needs in mind. The patient and family or caregivers should be educated on the plan of care as prevention and treatment will require a collaborative approach (AHRQ,2014).

Skincare, nutrition, and repositioning are vital to maintaining skin integrity. The following are suggestions from the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP, 2016) to decrease the risk of pressure injuries.

Related to skincare:

- Daily head-to-toe assessments of the skin with a focus on pressure points such as the coccyx, heels, or any bony prominence should be performed.

- Daily hygiene with a bed bath or shower is recommended, focusing on any folds in the skin and the perineal area.

- Cleanse skin promptly after an episode of incontinence.

- Use pH balanced cleansers and moisturizers daily to avoid dry or cracked skin (NPUAP, 2016).

Related to nutrition:

- The patient should be screened for malnutrition using a reliable tool and referred to a dietician if at risk.

- Daily weights should be done during hospitalizations and weekly weights for long-term care or home care patients; nutritional supplementation should be provided as needed (NPUAP, 2016).

Related to repositioning and mobilization:

- Establish a turning schedule based on pressure injury risk.

- Reposition the patient frequently and avoid positioning over areas of erythema or an existing pressure injury.

- Ensure heels are not touching the bed; elevate with pillows or use pressure relief devices.

- Pressure relief devices such as mattress toppers or chair cushions should be used as needed.

- Use breathable incontinency pads or briefs.

- Use thin foam or breathable dressings under medical devices to avoid injury (NPUAP, 2016).

Suicide

According to the CDC (2018), suicide rates are rising across the US, with nearly 45,000 lives lost to suicide in 2016. More than half of those dying by suicide did not have a known mental health condition. The contributing factors are relationship problems, substance abuse, physical health, job, money, legal or housing stress. Due to the increasing incidence, the TJC integrated suicide risk into its 2020 NPSGs, NPSG 15.01.01: Reduce the risk for suicide. The TJC indicates that suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the US and extremely high in rural areas (TJC, 2020a). Although most people who die by suicide have received healthcare services for related or unrelated issues in the year before their death, healthcare providers often do not detect suicidal thoughts (CDC, 2018).

There is no typical description of a person who will attempt suicide. Individuals who fit the textbook profile rarely attempt suicide, while others who are not readily identified die by suicide. Healthcare providers in all settings must focus on the detection of suicidal ideation in patients and follow up to take appropriate steps for their safety. Retrospective studies profiling individuals who have died from suicide or attempted suicide identify the following characteristics:

Demographics:

- Military veterans;

- Men over the age of 45 years; and

- Adolescents (CDC, 2018).

Other risk factors:

- Mental or emotional disorders, especially depression or bipolar disorder (but may be undiagnosed);

- Previous suicide attempts or self-inflicted injury (especially within weeks to one year of another suicide attempt);

- History of trauma or loss;

- Family history of suicide, such as child abuse;

- Bereavement;

- Economic loss;

- Serious illness, chronic pain, or impairment;

- Alcohol and drug abuse;

- Social isolation;

- History of aggressive or antisocial behavior;

- Discharge from inpatient psychiatric care (especially within the first weeks or months of discharge); or

- Access to lethal means coupled with suicidal thoughts (CDC, 2018).

Assessing suicide risk remains a challenge. The TJCs Sentinel Event database reports 1,089 suicides from 2010 to 2014 among patients receiving care in a facility staffed around-the-clock, including a hospital ED, or within 72 hours of discharge. A failure in assessment was the most commonly documented root cause. The TJC identified that 21.4% of accredited behavioral health organizations and 5.14% of accredited hospitals were non-compliant in 2014 with NPSG 15.01.01 Element of Performance 1 – Conduct a risk assessment that identifies specific patient characteristics and environmental features that may increase or decrease the risk for suicide. This goal is now retired and replaced with the current NPSG 15.01.01 Reduce the risk for suicide. Presently, healthcare organizations and communities lack adequate suicide prevention resources, which leads to a decrease in the detection and treatment rate of people at risk (TJC, 2020a).

Suicide is considered a sentinel event, causing the healthcare organization to implement an RCA to determine the cause(s), as seen in Figure 5.

Prevention of Suicide

Healthcare providers in primary, emergency, and behavioral healthcare facilities hold important roles in detecting suicidal ideation in acute or non-acute care settings. Assessment findings should be used to determine the level of safety measures required. The TJC recommends the following three steps in detecting patients at risk (TJC, 2020a).

- Review each patient’s personal and family medical history for suicide risk factors.

- Screen all patients for suicidal ideation, using a standardized, evidence-based screening tool.

- Review screening questionnaires before the patient leaves the appointment or is discharged (TJC, 2020a).

When a patient assessment indicates, action should be taken immediately, as it is a life or death matter. If an at-risk patient denies or minimizes suicide risk or declines treatment, the healthcare provider should request the patient's permission to contact friends, family, or outpatient treatment providers to corroborate the information. HIPAA allows a clinician to make these contacts without the patient's permission when the clinician believes the patient may be a danger to self or others (US Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2020). Additional suggestions from the NPSGs include:

- One-on-one observation in a safe healthcare environment is essential for patients assessed to be an acute suicidal threat.

- Personal and direct referrals to outpatient behavioral health and other providers for follow-up care within one week of initial assessment should be expected. It should not be left up to the patients to make their appointments.

- All patients with suicidal ideations and their family members should be given the number to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 1-800-273-TALK (8255), as well as local crisis and peer support contacts.

- Keep these patients away from anchor points for hanging and materials that can be used for self-injury, such as bandages, sheets, restraint belts, plastic bags, elastic tubing, and oxygen tubing. This includes the screening of visitors.

- Conduct safety planning collaboratively with the patient to identify possible coping strategies. Resources for reducing risks should be identified and given to the patient. Evidence indicates that a "no-suicide contract" does not prevent suicide and is not recommended by experts in the field. The safety plan details should be reviewed with the patient at every interaction until the patient is no longer considered at risk for suicide.

- Restrict access to lethal means, such as firearms, knives, prescription medications, and chemicals. Discuss ways of removing or locking up firearms, possible weapons, medications, and chemicals with family members or significant others. Healthcare institutions should keep medications, chemicals, supplies, and equipment secured (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2019).

Additional recommendations from the TJC address behavioral health treatment and discharge. Evidence-based treatments and discharge plans must be implemented, and transition and follow-up care should be well coordinated with all providers (TJC, n.d.e).

- Establish a collaborative, ongoing, and systematic assessment and treatment process with the patient involving the patient's other providers, family, and friends as appropriate.

- Develop treatment and discharge plans that are specific and directly target suicide prevention.

- Post-discharge prevention includes evidence-based interventions that emphasize patient engagement, collaborative assessment and treatment planning, problem-focused clinical intervention skills training, shared service responsibility, and proactive and personal clinician involvement in care transitions and follow-up care (TJC, n.d.e).

The following recommendations for education and documentation apply to all care providers and settings:

- Educate all staff in patient care settings about how to identify and respond to patients with suicidal ideations.

- Document decisions regarding the care and referral of patients at risk of suicide (TJC, n.d.e).

Community awareness of the prevalence of suicide and efforts to reduce its incidence is highlighted in the World Suicide Prevention Day and Suicide Prevention Awareness Week. Whenever possible, the nurse should engage in these well-organized public education campaigns regarding the risk factors for suicide and how to intervene if individuals are concerned that their loved one is at increased risk. Organizations that conduct research, increase awareness of mental health issues and suicide, and make resources for suicide prevention available include the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the National Alliance of Mental Illness (NAMI), the CDC, the QPR Institute, and the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (CDC, 2019b).

Medical Device Alarm Safety

Alarms are common in many medical devices used in patient care, including electrocardiogram (ECG) machines, pulse oximetry devices, telemetry monitors, ventilators, and infusion pumps. Alarms are important when providing safe patient care, but technology limitations often occur in practice. Such challenges include:

- Similar sounds;

- Default settings not adjusted to the patient population;

- Failure to respond – more than 85% of alarm signals do not require clinical intervention;

- Alarm fatigue and desensitization;

- Clinicians decrease alarm volume, ignore, turn off alarms, or adjust outside of safe parameters;

- Inadequate staffing and/or training.

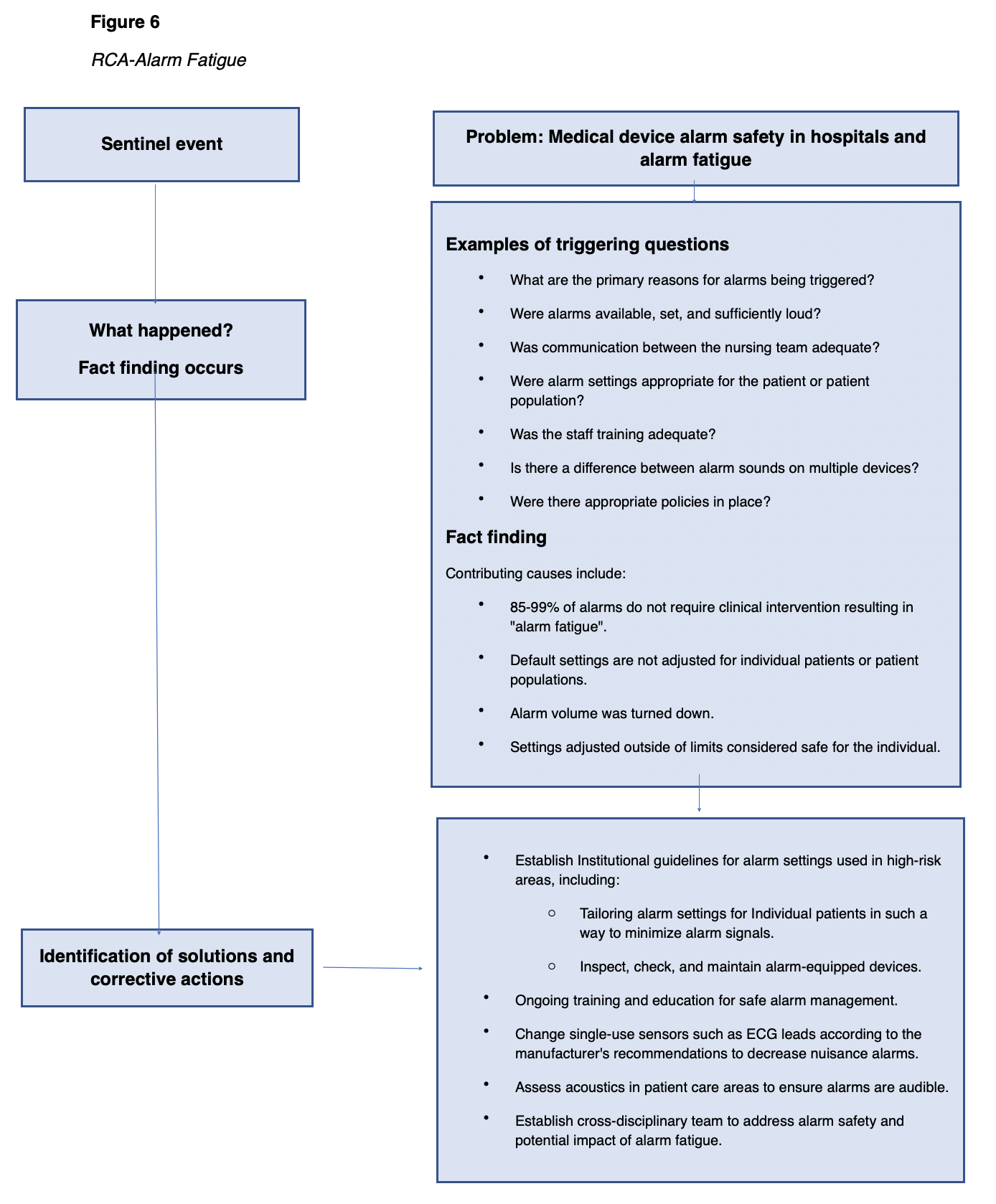

The Boston Globe reported in 2011 that over 200 deaths in a five-year period were attributed to the failure to respond to physiologic alarms appropriately, most commonly related to a failure to respond to active alarms. This may be difficult to understand unless one is made aware that a single patient care unit may have more than 100 alarm signals in a single shift. The data demonstrates a significant human error component. Many devices provide appropriate alarm systems if they are used independently of other devices, if the staff understands the parameters of the alarms, and if settings are appropriately set to the patient population (AHRQ PSN, 2019a). See Figure 6 for an RCA of Alarm Fatigue.

Prevention of Alarm Fatigue Errors

The prevention of injury related to the use of medical devices equipped with alarms aims to reduce the chance of human error through training, technology, monitoring, and increased awareness. Institutions must demand that manufacturers of devices provide a variety of sounds so that alarms can be distinguishable. An assessment of unit acoustics with correction of impediments to sounds being clearly heard must be conducted at the institutional level (TJC, 2013).

Multidisciplinary teams, including experts on human behavior, should be used to create policies and processes for setting and monitoring alarms at the initiation of device use and during handoff communications. Settings for specific patient populations should be identified and communicated for patient-care units and processes established for reviewing indications for individualized settings. For example, an adjustment to the preset delay of a pulse oximetry monitor from 5 seconds to 10 seconds would decrease alarms caused by movement and temporary oxygen changes (TJC, 2013).

Ongoing training and education should be aimed at:

- Changes in the technology used,

- Appropriate application and changing of sensors,

- Institutional policies and procedures,

- Processes for checking sensors and alarm settings,

- Communication amongst the team members (TJC, 2013).

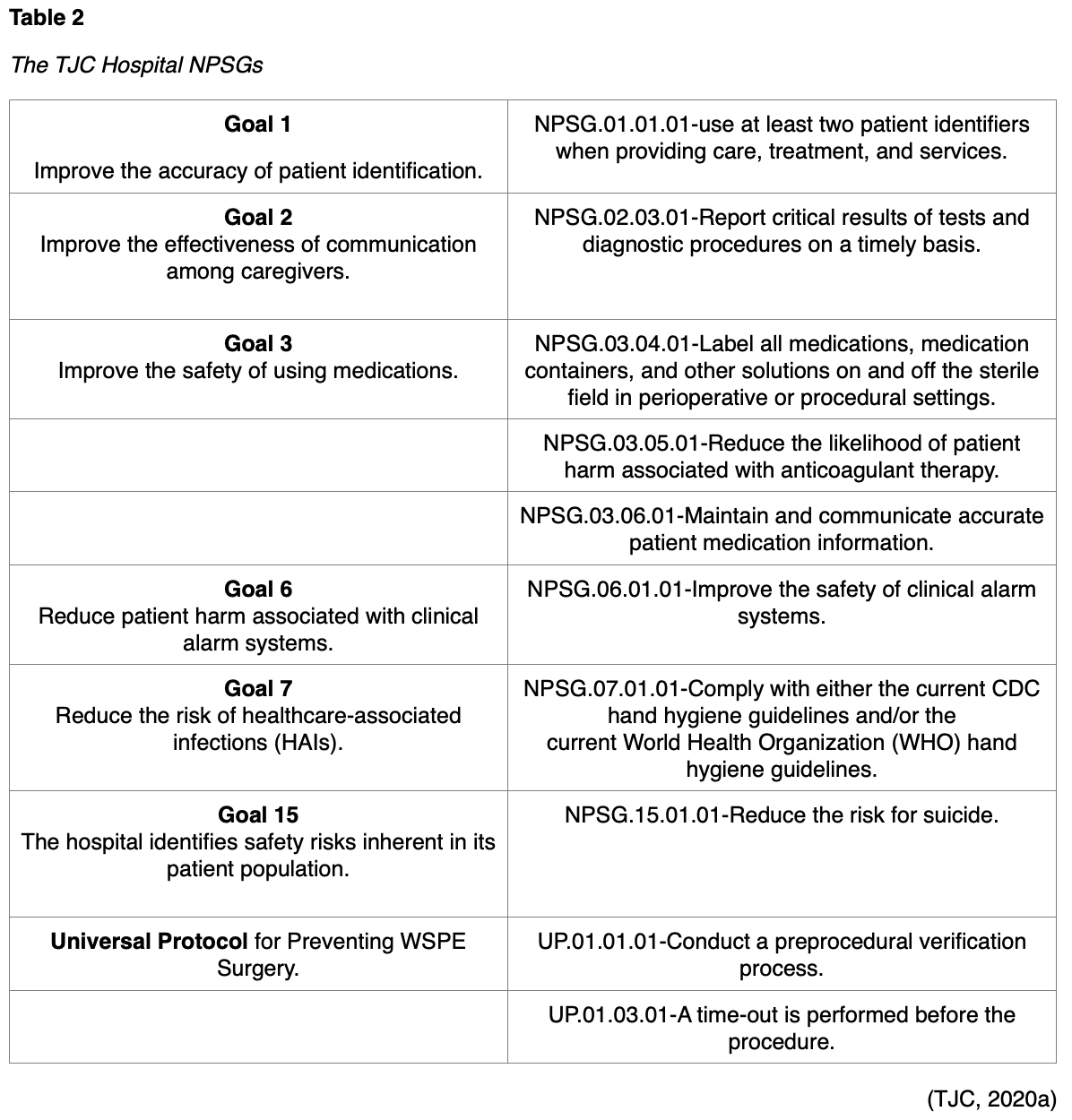

Surgical Errors

Mistakes are expected in any situation involving humans and are inevitable when considering that humans are involved in the performance of more than 200 million surgeries annually around the world. This is not to imply that errors are acceptable, but to recognize that it is unrealistic to prevent all errors and instead should be limited. Several initiatives have been implemented since 2005 by national and international organizations such as the IHI, TJC, and the WHO, yet sentinel or adverse events related to surgical procedures continues to be high. Analysis of data has identified that often these events have their root causes in errors occurring before or after the procedure rather than mistakes made during the operation. Contributing factors include a breakdown in communication within and amongst the surgical team, other care providers, patients and families; errors or delays in diagnoses; and delays or failure to treat (TJCCTH, n.d.c).

Examples of significant types of errors that occur in the surgical setting include infection, WSPE, and unintended foreign objects. Many of the contributing or causative factors are similar by RCA yet processes to prevent them will vary. The time-out used in the prevention of WSPE would not prevent the contamination of fields or leaving a surgical instrument in a patient (TJC, n.d.d).

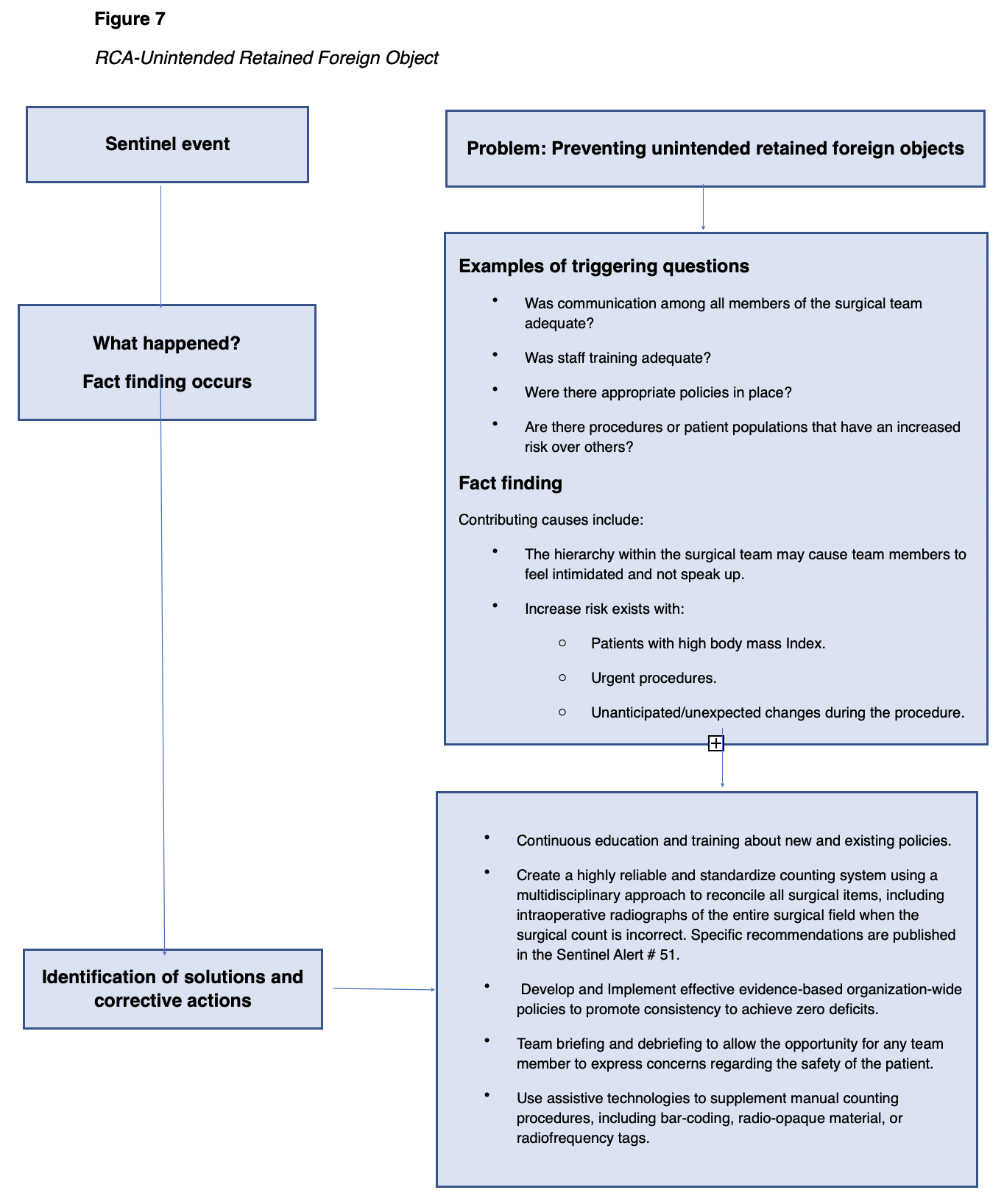

Surgical errors can lead to a sentinel event causing the healthcare organization to implement an RCA to determine the cause(s). Figure 7 depicts an RCA identified by the TJC Sentinel Event Alert #51 involving the prevention of untended retained foreign objects (TJCCTH, n.d.c)

Prevention of Unintended Retained Foreign Object

In order to limit human error, there must be a culture that recognizes that they occur and a well-designed evidence-based system in place to prevent, recognize, and remedy them when they do occur. These processes should be developed by a multidisciplinary team that includes experts in human behavior; it must contain checks and balances to ensure that errors are more likely to be caught before they happen. Blame should not rest upon an individual, and it is important to consider that each step has the potential for failure (TJC, n.d.d).

Hand-off Communication

Too often, individual healthcare professionals' efforts to provide safe and effective care fail as the patient is handed off to another healthcare provider for continuing care or services. TJC (2017a) defines the handoff as the "transfer and acceptance of patient care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing patient-specific information from one caregiver to another or from one team of caregivers to another to ensure the continuity and safety of the patient's care." (para. 1)

Effective hand-offs can be complex, and failures in this area have long been considered a significant contributing factor to sentinel events. Healthcare providers in a typical teaching hospital may conduct at least 4,000 handoffs each day. As such, it was addressed in the NPSGs in 2010. Despite this goal, a study of the Commission's sentinel event databases published in 2016 estimates that communication failures contributed to 30% of malpractice claims and 1,744 deaths over five years (TJC,2017b).

The following root causes for poor handoff communication were identified through the Robust Process Improvement project enacted in 10 hospitals: delays, inattention, lack of knowledge, lack of time, poor timing, interruptions, distractions, and lack of standardized procedures. Institutions have been able to significantly reduce ineffective handoff communication and related adverse events by using a variety of communication tools such as evidence-based checklists and tools, such as the SBAR tool (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) and I-PASS (illness severity, patient summary, action list, situation awareness and contingency plans, synthesis by the receiver; TJC, 2017b).

TJC has provided "8 Tips for High-Quality Handoffs" to assist caregivers in making high-quality handoffs (JC, 2017a). A brief synopsis of the tips from Sentinel Alert issue #58 is below.

- Determine the critical information that needs to be communicated.

- Use standardized tools to communicate.

- Do not rely only on electronic or paper communication. Face-to-face or phone communication allows for the receiver to ask questions and seek clarification.

- Combine information from multiple sources and communicate at one time.

- Verify that the receiver gets minimal essential information.

- Handoff communication should take place in a designated "zone of silence" free from non-emergency interruptions.

- Include all team members in handoff and, if possible, the patient and family members.

- Use electronic health records and other technologies to enhance communication, but do not solely rely on them (TJC, 2017a).

Communication is often determined to be the root cause of a variety of sentinel events, even if not the sentinel event itself. Analysis communication must be completed to determine how to make patient care safer. Nurses make great efforts to deliver safe and effective care and do not intend to create unsafe conditions through incomplete or inaccurate communication when transferring responsibilities of care to another professional (TJC, 2017b).

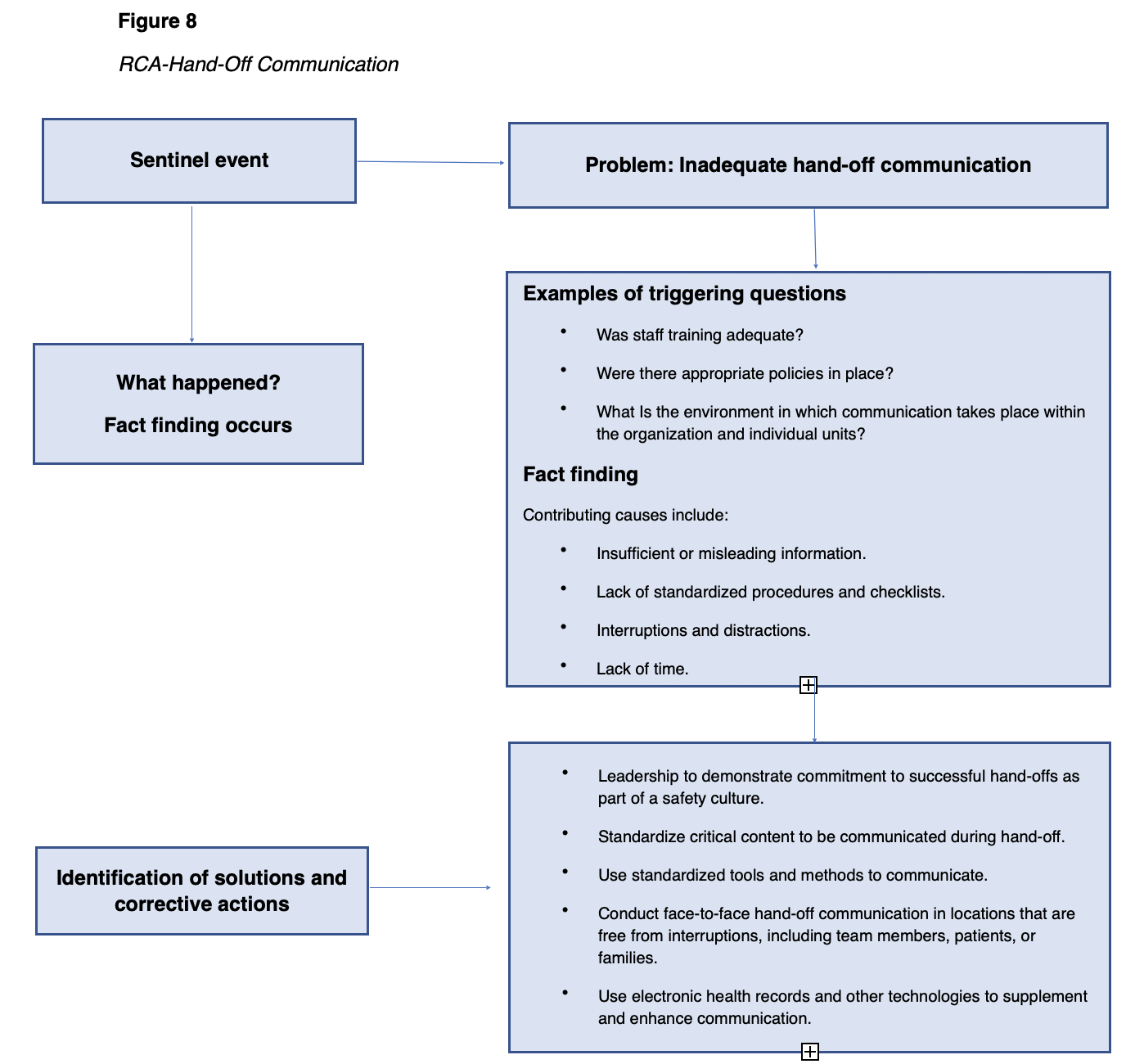

Handoff communication can lead to a sentinel event causing the healthcare organization to implement an RCA to determine the cause(s). Figure 8 depicts an RCA identified by the TJC Sentinel Event Alert #58 for inadequate handoff communication (TJC, 2017a).

Prevention of Handoff Communication Errors

Effective communication needs to be supported throughout the entire organization. It requires sufficient time, staffing, space, standardized tools and expectations, and the encouragement of questioning in a safe environment. Multidisciplinary teams should develop the protocols and tools for guiding communication between departments and disciplines. Protocols should favor face-to-face handoffs, provide for quiet, uninterrupted environments, the participation of team members, including the patient, and use of standardized tools to guide communication. Education and training should include role-playing sessions and follow-up monitoring for all members of the health provider team (TJC, 2017b).

Patient Identification

An error while identifying a patient can occur in any aspect of the healthcare system, such as clinical care, medication administration, or billing, and in every healthcare setting, from hospitals to walk-in clinics and doctors' offices. Healthcare providers are acutely aware of how egregious these errors are. Most patient identification mistakes are caught before the patient is harmed. However, research indicates that patient identification errors leading to temporary or permanent harm or death have occurred. TJC listed improving the accuracy of patient identification as one of their 2014 NPSGs and it remains at the top of the 2020 NPSGs (TJC, 2020a).

Three problems commonly associated with patient identification errors are (a) the institution does not have formal policies, (b) existing policies are not followed, and (c) the intention of the policy is inadequate. When policies do exist, the reasons most often given for noncompliance with the policy were time constraints, language barriers, and yes/no questions (Choudhury & Vu, 2020).

Patient identification errors most commonly occur in the following areas:

- Registration (i.e., facilities that do not require photo ID during registration),

- Wristband accuracy and use (i.e. missing, incorrect, incomplete, or poorly designed wristbands),

- Order entry and charting (i.e., software issues or information placed in the wrong patient’s chart),

- Medication administration (i.e., not following protocols prior to administering medications), and

- Surgery (i.e., WSPE; Choudhury & Vu, 2020; ECRI Institute, 2016).

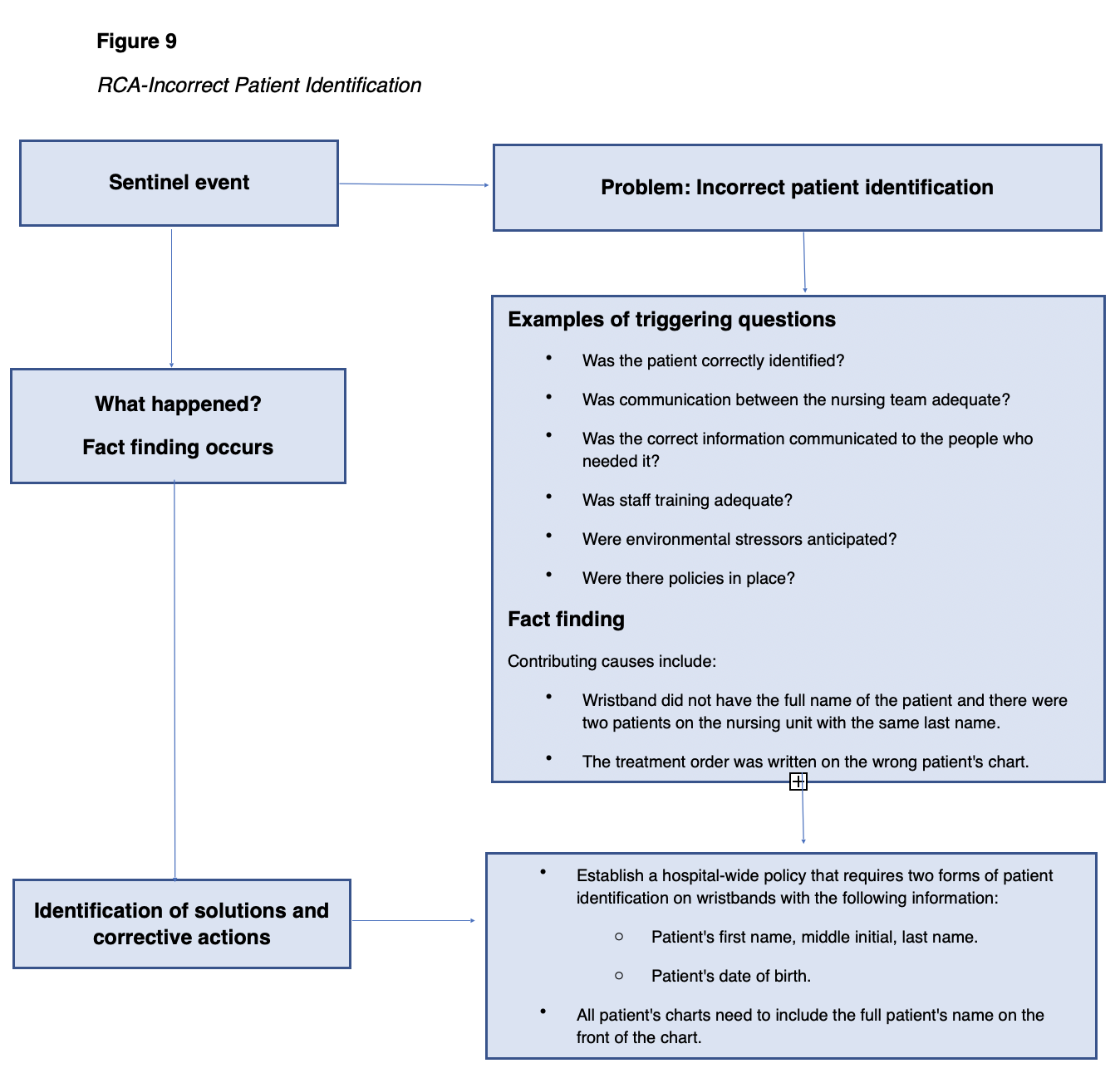

Research suggests that compliance with patient identification protocols when administering medications was higher among new nurses than with more experienced nurses. WSPE appear to be typically due to communication or system errors often attributed to the diagnosis process when the incorrect medical record, radiographs, or laboratory samples are used (ECRI Institute, 2016). Any of the above patient misidentifications can lead to a sentinel event causing the healthcare organization to implement an RCA to determine the cause(s). Figure 9 depicts an RCA identified by the NPSG as Goal #1 for patient identification (TJC, 2020a).

Prevention of Incorrect Patient Identifier Errors

The goal for improving patient identification accuracy is to reliably identify the individual for whom the treatment is intended, matching the treatment to the individual. This can be achieved by using two patient identifiers when administering medications and blood, when collecting specimens for testing, and when carrying out treatments. Additionally, all containers used for blood and other specimens should be labeled in front of the patient (ECRI Institute, 2016).

In addition, healthcare organizations should establish standardized approaches for patient identification, particularly within healthcare systems. Policies need to be established and followed consistently, especially for identifying non-verbal patients and patients with the same name. When addressing a patient, the nurse should avoid questions with yes/no answers. Patients may be embarrassed to admit that they did not hear or understand the question, automatically answering the question with a yes. Education is an important factor in preventing patient identification errors and needs to be incorporated into orientation and continuing education for all employees. The nurse can also involve the patient and family members by educating the public regarding the risks of patient misidentification (ECRI Institute, 2016).

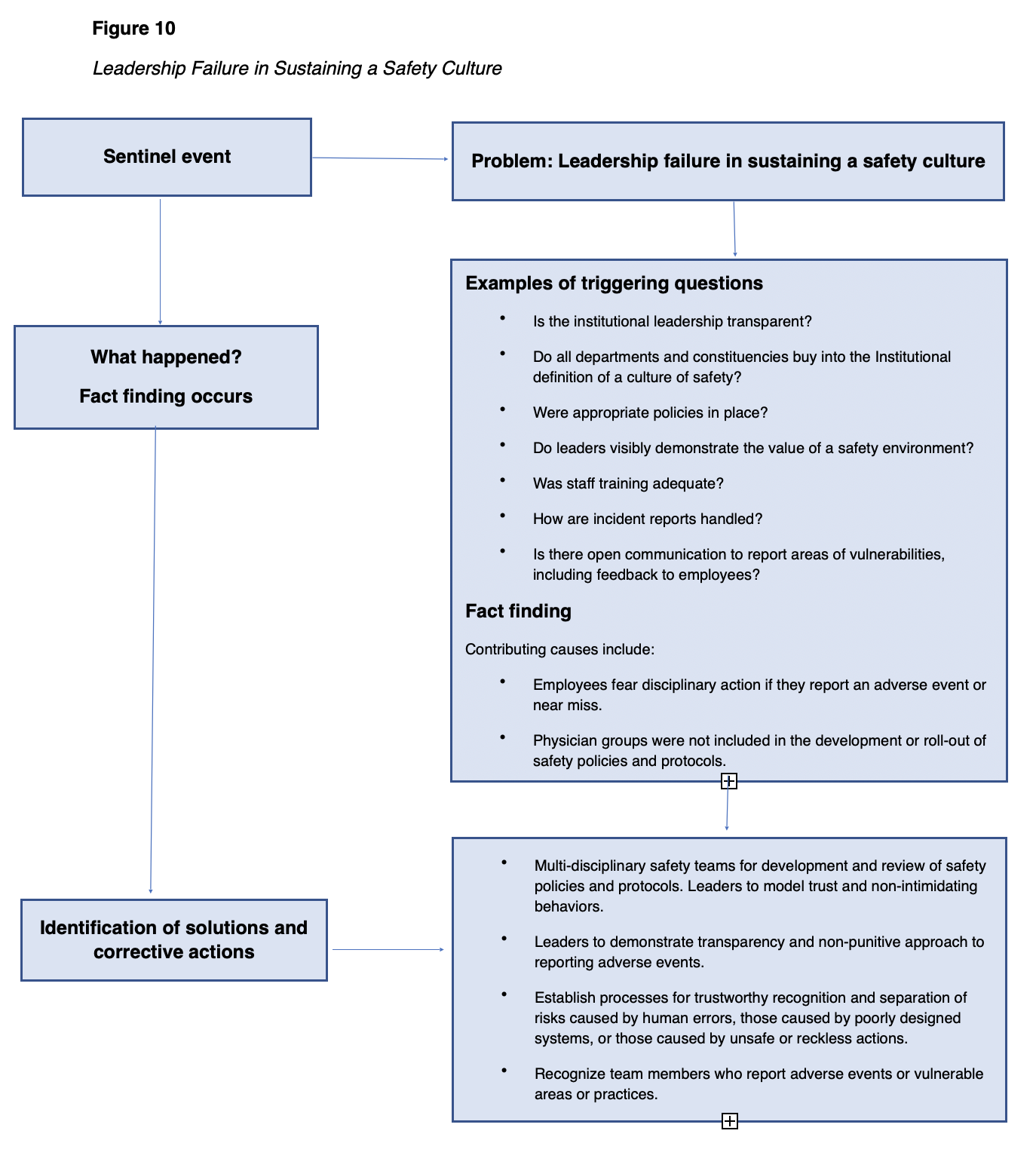

Leadership's Role in Creating a Safety Culture

As noted in each of the NPSG categories, much of the RCA process focuses on the systemic failures of the organization that led to the event in question. The leadership of each healthcare organization is accountable for creating and maintaining an environment that is safe for patients, employees, and visitors. Competent leaders recognize that systemic flaws or weaknesses exist in every organization; despite policies, protocols, and training, the potential for error exists because humans make mistakes. Leadership failure contributes to many adverse events, such as ineffective handoff communication, WSPE, and delays in treatment (TJC, 2020a).

Without an environment of safety with organizational support and monitoring, the creation of policies or the purchase of the latest technology will not significantly reduce the number of adverse incidents or near misses. An environment of safety requires all healthcare team members to openly communicate, question, and confront concerns regardless of the individual's role in the institutional hierarchy. For example, the surgical technician or circulating nurse must be free to interrupt a surgery because of perceived contamination, wrong site, or wrong count by the physician. It takes sufficient time, space, and planning for a change of shift report that includes pertinent information and encourages questions in a quiet and interruption-free environment (Dekker & Breakey, 2016).