About this course:

The purpose of this activity is to examine the pharmacological management of some of the most common mental health disorders, including ADD/ADHD, OCD, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia/psychosis, providing a detailed account of the benefits, risks, adverse effects, and monitoring parameters of these medications in an effort to educate the advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) prescriber and safeguard patient care.

Course preview

At the completion of this activity, the APRN should be able to:

- Briefly define the pathophysiology, and discuss the benefits, risks, adverse effects, and monitoring parameters for drugs used for the treatment of attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD/ADHD).

- Briefly define the pathophysiology, and discuss the benefits, risks, adverse effects, and monitoring parameters for drugs used for the treatment of depression.

- Briefly define the pathophysiology, and discuss the benefits, risks, adverse effects, and monitoring parameters for drugs used for the treatment of anxiety disorders, including obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

- Briefly define the pathophysiology, and discuss the benefits, risks, adverse effects, and monitoring parameters for drugs used for the treatment of bipolar disorder.

- Briefly define the pathophysiology, and discuss the benefits, risks, adverse effects, and monitoring parameters for drugs used for the treatment of schizophrenia/psychosis.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2019), mental health disorders are characterized by a combination of abnormal thoughts, perceptions, emotions, behavior, and relationships with others. Those suffering from mental health disorders are often untreated or undertreated. In low- to middle-income countries, around 80% of those with mental health disorders receive no treatment, and in high-income countries the percentage of those with mental health disorders who receive treatment is between 35-50%. However, among those who do receive treatment, it is often suboptimal and insufficient. The WHO Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020 aims to use evidence-based guidance, tools, and training to help improve the amount and quality of mental health care offered worldwide by increasing leadership, providing comprehensive and integrated care in community-based settings, implementing strategies for promotion and prevention, and strengthening evidence and research (WHO, 2019).

ADD/ADHD

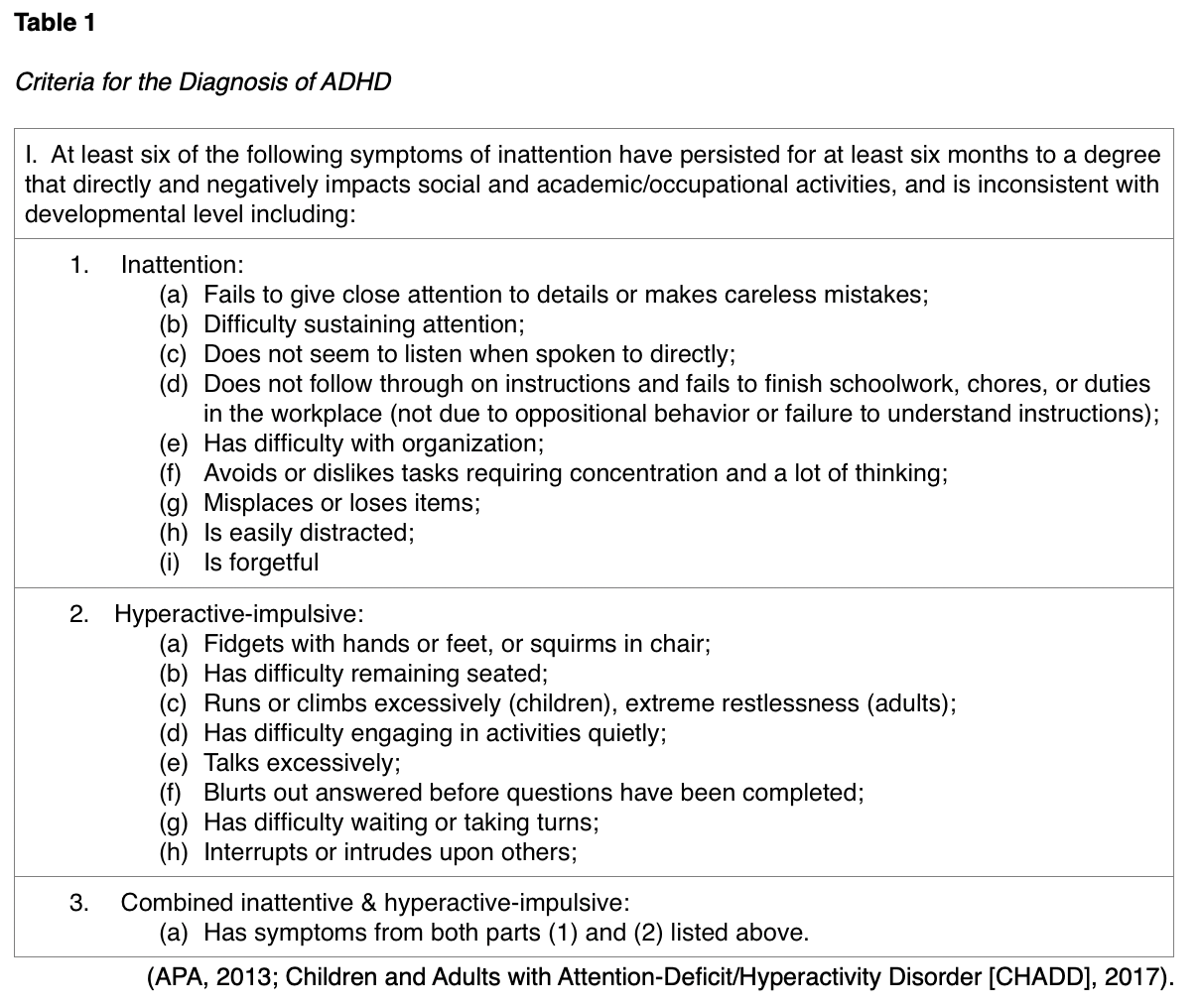

According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, 2019a), ADD/ADHD disorders are characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention with or without a hyperactivity-impulsivity component. The condition can affect both children and adults and is marked by its interference with functioning, development, or daily life, as it can affect attention, executive function, and working memory. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) revised some of the diagnostic criteria for ADHD in 2013, changing prior “subtypes” to “presentations” that can change throughout life, adding a severity scale, and requiring more pervasiveness of symptoms in various settings to qualify. In diagnosing ADHD in adults, the DSM-5 now advises clinicians to look back to middle childhood (age 12) and the teen years when making a diagnosis for the beginning of symptoms, versus back to childhood (age 7), as previously advised in the DSM-IV. Furthermore, the DSM-5 recognizes that a diagnosis of ADHD and autism spectrum disorder can coexist. There are three presentations of ADHD which include inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive, and combined inattentive & hyperactive-impulsive. While there is no diagnostic laboratory or biomarker test for the diagnosis of these disorders, there are several criteria of symptoms, which are listed in Table 1. When diagnosing the condition, children should have six or more symptoms of the disorder, whereas older teens and adults should have at least five symptoms (American Psychiatric Association Publishing [APA], 2013).

The symptoms of ADHD affect each individual to varying degrees. The DSM-5 helps clinicians designate the severity of the condition as mild, moderate, or severe, based on the following criteria:

- Mild: few symptoms beyond the required number for diagnosis; symptoms result in minor impairment at home, school, work, or in social settings;

- Moderate: simply defined as symptoms or functional impairment between ‘mild’ and ‘severe’;

- Severe: many symptoms are present in excess, beyond the number required to make a diagnosis of the disorder; multiple symptoms are severe, or symptoms extremely impair the individual at home, school, work, or in social settings (CHADD, 2017).

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) revised their clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of ADD/ADHD disorders in children and adolescents in 2019. Among preschool aged children (age four to sixth birthday), parent training in behavioral management (PTBM) is recommended as the primary intervention for ADHD, as well as for children with ADHD-like behaviors whose diagnosis is not yet confirmed. Pharmacologic treatment with methylphenidate (Ritalin) may be considered only if behavioral therapy is ineffective or does not provide significant improvement and there is moderate-to-severe continued disturbance in the four- through five-year-old child’s functioning. The guidelines encourage clinicians to weigh the risks of prescribing the medication prior to the age of six years, against the harm of delaying treatment. Elementary and middle school-aged children (six years to the 12th birthday) should receive treatment with PTBM, behavioral classroom intervention, and medication. Educational interventions and individualized instructional support should be provided within the school environment, classroom placement, and additional essential components of the treatment plan, which often includes an individualized education program (IEP) or rehabilitation plan. Adolescents (12 years to the 18th birthday) should receive medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) with the adolescent’s consent, preferably with behavioral interventions, and the same educational interventions as outlined above (AAP, 2019). Medications are also commonly used during adulthood, as up to one-third of children with ADHD continue to have symptoms into adulthood (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019). There is no cure for ADHD, and therefore the goal of medication use is to lessen symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity, and improve the ability to concentrate, focus, work, and learn (CHADD, 2018).

The pathophysiology of ADD/ADHD is not entirely clear but is premised on a complex neurobiological basis involving multiple brain pathways. Neurotransmitters are endogenous chemical messengers within the brain that help transmit signals that are necessary for normal functioning and are thought to play a role in ADD/ADHD disorders, which is why pharmacotherapy is the mainstay of treatment for adolescents and adults. The three neurotransmitters implicated in ADD/ADHD disorders include dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. It is postulated that a deficiency in these vital chemical messengers is linked to the development of the symptoms of ADD/ADHD. Dopamine is involved with movement, attention, and motivation; norepinephrine plays a role in maintaining mental activity, regulating mood and excitability, problem-solving, and memory; and serotonin influences mood, sleep, memory, and social behavior. Therefore, medications targeting these neurotransmitters are considered the mainstay of pharmacological treatment (Tarraza & Barry, 2017).

There are two classes of medications that are commonly prescribed for the treatment of ADHD; stimulants and nonstimulants. These medications work primarily by blocking the reuptake of and increasing the release of the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine, improving cognition and attention (NIMH, 2016). Stimulants are the most widely used and well-known class of medications for the management of ADHD-related symptoms and have been shown to reduce symptoms in 70-80

...purchase below to continue the course

Stimulants

Stimulants are all categorized by the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) as Schedule II with a high abuse potential and previously by the FDA as pregnancy category C (risk cannot be ruled out). These medications were first administered to children with behavioral and learning disorders in 1937 and there are hundreds of controlled studies (including more than 6,000 children, adolescents, and adults) to determine the effects of these medications on a short-term basis. There are no long-term studies (more than a few years) of the effects of these medications as those studies would necessitate the withholding of treatment over many years from patients with significant impairment, which has been deemed unethical. However, many individuals have used these medications for many years without serious adverse effects. Stimulants are generally comprised of different types of methylphenidate and amphetamine and they function to produce a calming effect on hyperactivity by increasing levels of dopamine in the brain. The most common stimulants used for ADHD include methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta, Metadate, Focalin), and dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine, Dextrostat). They are available as IR formulas (last about 4 hours), LA formulas (variable from 6-12 hours), or ER preparations (up to 24 hours) (CHADD, n.d.). Many prefer LA or ER formulations as these may reduce the “ups and downs” throughout the course of the day and eliminate the need to dose medication at school or work (AAP, 2019).

Amphetamines induce central nervous system activity, activating the acute stress response ("fight or flight), thereby producing a paradoxical calming effect. Activation of the central nervous system creates physiological changes as if the body were stressed or under threat. Amphetamines stimulate the release of adrenaline, raises cortisol levels and other stress hormones, causing increased heart rate and blood pressure. Blood flow is redirected to the muscles and away from the brain. In small doses, amphetamines can alleviate tiredness and help the patient to feel alert and refreshed. Some common types of amphetamines include dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine), dextroamphetamine/amphetamine (Adderall), amphetamine salt combo XR (Adderall XR), and lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse). Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine (Adderall) is considered first-line pharmacological treatment for ADHD and is widely used in individuals six years of age and older. Proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole (Prilosec) and esomeprazole (Nexium) can interfere with absorption of the medication, and there is a rare risk of sudden death in patients with cardiac history (AAP, 2019; NIMH, 2016). Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) is a LA preparation and differs from other medications in this class due to its pharmacokinetics. It is considered a prodrug, which means it must undergo chemical conversion by metabolic processes before becoming an active agent. It does not convert to its active formulation until it reaches the gastrointestinal tract and therefore may take 60 to 90 minutes to take effect. The drug has less abuse potential than medications such as dextroamphetamine/amphetamine (Adderall), as it cannot be absorbed intravenously or transmucosally (AAP, 2019).

The side effects of stimulants may include increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, anxiety, decreased appetite, sleep problems, personality changes, tics, stomach pain, or headaches. Less commonly reported side effects include allergic reactions, fever, arthralgia, psychosis, and depression. Sudden death is a rare adverse effect seen in patients with preexisting cardiac conditions. These drugs should be used with caution in patients with hypertension, seizures, heart disease, glaucoma, liver disease, kidney disease, or anxiety disorders (NIMH, 2016). Clinicians should counsel patients on strategies to manage insomnia including taking the medication prior to noon, limiting or avoiding caffeine intake, and good sleep hygiene practices. When insomnia requires pharmacological management, melatonin is encouraged as the initial agent, as it is natural and non-addicting. Some patients may require adjunctive prescriptive sleep aids, such as clonidine (Catapres) or trazadone (Desyrel), which may be used in both children and adults. Medications such as eszopiclone (Lunesta) and zolpidem (Ambien) should only be prescribed for adults and should be taken 30 to 60 minutes prior to bedtime (Tarraza & Barry, 2017).

The decision about which medication should be used to treat ADHD depends on a range of factors, including but not limited to the presence of comorbidities, risk for side effects of the medication, consideration of the individual’s compliance potential, as well as the potential for drug diversion. Stimulants carry risk for diversion, which is the practice by which legitimate stimulant prescriptions for ADHD are diverted for reasons other than treating ADHD. When taken in doses and via routes other than those prescribed, stimulants can increase dopamine levels in the brain in a rapid and highly amplified manner (similar to other drugs commonly abused, such as opioids), thereby disrupting normal communication between brain cells and producing euphoria. As a result, these biochemical processes and subsequent euphoric effects increase the risk of addiction. Therefore, prior to prescribing these medications, clinicians must first assess the patient’s risk for diversion, and then continue to reassess for this at each follow-up while continuing treatment (AAP, 2019). Following drug selection, clinicians are advised to “start low and go slow” when prescribing these agents, which means initially prescribing the lowest dose possible and gradually titrating the dose upward to minimize side effects. Most side effects of stimulants can be eliminated or decreased with this medication initiation plan. Some people describe a stimulant rebound during the time interval between dosing as the medication is wearing off in which they can experience a negative mood, fatigue, or hyperactivity. These symptoms can be managed by changing the dose level or schedule of IR formulas, or by switching to an LA formula if possible (CHADD, 2018).

Patients who are prescribed any type of amphetamines should have specific monitoring performed by prescribers at dedicated time points during treatment. At baseline, all patients should have their blood pressure, heart rate, height and weight evaluated. During dose adjustments, a weekly phone check-in or follow up appointment is advised to monitor for side effects and to particularly assess patients for tics or adverse effects. This allows the prescriber to track changes and severity of symptoms closely. Once the optimal dose is established, patients should have follow-up visits every one to three months. Routine laboratory testing is not advised unless there are specific concerns as based on the patient's clinical presentation (AAP, 2019).

Non-Stimulants

Non-stimulants are also highly effective in reducing ADHD symptoms, but they generally take longer to start working. Non-stimulants are often used in place of stimulants in patients who had unacceptable adverse effects or inadequate results with stimulants, or in combination with stimulants to enhance effects. Non-stimulants can help improve focus and attention and decrease impulsivity. Some of the most common types of non-stimulant medications include atomoxetine (Strattera), guanfacine (Tenex), and guanfacine ER (Intuniv). Atomoxetine (Strattera) alleviates inattention and hyperactivity symptoms of ADHD by selectively inhibiting the reuptake of norepinephrine. It is not a controlled substance and is thus determined to have low abuse potential. Atomoxetine (Strattera) has a slower onset, taking up to four weeks for the full effects of the medication to occur (NIMH, 2016).

Antihypertensives such as clonidine (Catapres, Kapvay) and guanfacine (Tenex, Intuniv) have been approved for ADHD symptoms in children such as hyperactivity and aggression; they may be helpful in adults, but studies are limited at this point. These drugs pose significant adverse effects, such as hypotension, sedation, and a potential for hypertensive rebound. Clonidine clonidine (Catapres, Kapvay) is an alpha-2 noradrenergic agent, and guanfacine (Tenex, Intuniv) is an alpha-2a noradrenergic agent, but both are believed to work by affecting the available levels of norepinephrine, and thus dopamine. Another option in adult ADHD patients is modafinil (Provigil), a wake-promoting agent that is currently approved by the FDA for narcolepsy and extreme fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis. It does not seem to have an effect on central dopamine or norepinephrine pathways, but instead indirectly activates the frontal cortex. A small study on adults with diagnosed ADHD showed favorable results from modafinil after a two-week trial in 48% of patients. This is limited and preliminary, but warrants further long-term studies and consideration (CHADD, n.d.).

Antidepressants that target the neurotransmitter norepinephrine are sometimes used in the treatment of ADHD, but these are not FDA-approved for this indication and are thus considered off label. Venlafaxine (Effexor) inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine. Buproprion (Wellbutrin) is a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) that helps improve concentration, focus, and reduce hyperactivity. Since it does not influence serotonin, it works differently than many other antidepressants. Possible side effects of buproprion (Wellbutrin) include anxiety, agitation, increased motor activity, insomnia, tremors or tics, dry mouth, headaches, nausea, and increased risk for seizures in people who are susceptible to them or who have a history of eating disorders. Less commonly, duloxetine (Cymbalta) may be used; it works by blocking the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin (CHADD, n.d.). Like atomoxetine (Strattera), these drugs are not controlled substances, and have low abuse potential, but should be used with caution and in conjunction with extensive patient counseling regarding the possible side effects and risks. They are not recommended for children with depression and should be used with caution in adolescents due to increased risk of suicide (WHO, 2019).

Depression

According to the WHO (2019), as many as 300 million people worldwide are affected by depression, with women more commonly affected than men. Depression can lead to significant disability and is characterized by a period of at least two weeks of sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, guilt, low self-worth, disturbed sleep, poor appetite, tiredness, and/or poor concentration. Severe depression can lead to suicide (WHO, 2019). Depression has a variety of causes which can include genetics, environmental, psychological, and biochemical. It can be persistent (also called dysthymia, lasting at least two years), postpartum (extreme sadness, anxiety, and exhaustion after giving birth), psychotic (with delusions or hallucinations), seasonal (symptoms appear during the winter months when there is less natural sunlight and is accompanied by increased sleep, weight gain, and social withdrawal), or bipolar (a separate mood disorder, but which includes periods of depression) (NIMH, 2018b). Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, which can be diagnosed in children and adolescents, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder, a hormone-induced depression in women, are depressive disorders that have been recently added to the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). Depression can occur in children and adolescents, but is most common in adults, and often presents as irritability or anxiety in children (NIMH, 2018b).

Risk factors for depression include personal or family history, major life change/stress/trauma, and certain physical illnesses or medications (such as diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and Parkinson’s) (NIMH, 2018b). A previously accepted theory that depression stems from a chemical imbalance in the brain regarding the monoamines serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine has shifted over the last 15 to 20 years. Theories regarding alterations in brain architecture and complex circuitry have led researchers to question if the neurotransmitters are not simply a messenger of information or symptom as opposed to the cause itself. Advancements in the fields of genetics and functional neuroimaging have opened new and exciting investigational possibilities and altered the way depression is viewed in the last 20 years, hopefully leading to changes in treatment down the road (Goldberg, 2018). Cannabinoids may be a possibility for future further study, but at this time there exists only very low-quality evidence which suggested no benefit from the use of cannabinoids in depression (Whiting, et al., 2015).

While mild to moderate depression can be effectively treated with therapy alone (cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), psychotherapy), moderate to severe cases of depression often require the addition of medication. It is important to note that there are numerous additional nonpharmacological treatment options such as acupuncture, mindfulness training, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) that are beyond the scope of this module. These are valid treatment options that should be explored and discussed as alternatives to pharmacological treatment, or as part of an adjunctive therapy regimen (WHO, 2019). There are a few pharmacological agents that are available over the counter and without a prescription for the management of depression. These include hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort), omega-3 fatty acid (fish oil), and s-adenosyl methionine (SAM-e). These drugs have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of depression and continue to remain under study. Although patients do not require a prescription to obtain these drugs, they still pose risk for significant adverse effects and drug interactions. Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort) is notorious for interacting with several prescription drugs, either expediting or diminishing the metabolism of the prescribed agent leading to reduced efficacy or higher toxicity. For example, patients should be warned to never take hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort) with a prescribed antidepressant as the combination leads to increased levels of serotonin in the body, which can cause mild to severe effects (National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health [NCCIH], 2017).

The majority of FDA-approved prescription medications for depression target the three neurotransmitters traditionally associated with depression: serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. These medications, often referred to as antidepressants, usually take two to four weeks before they take effect. Symptoms such as sleep, appetite, and concentration often improve prior to a notable change in mood. Due to their side effect profiles, most antidepressants need to be tapered up slowly when starting therapy and tapered down gradually when stopping treatment. If stopped abruptly, some types of antidepressants pose risk for withdrawal-like symptoms such as dizziness, headache, flu-like syndrome (tiredness, chills, muscle aches), agitation, irritability, insomnia, nightmares, diarrhea, and nausea. In women of childbearing age, they should be warned that most antidepressants were previously categorized by the FDA as pregnancy category C (risk cannot be ruled out) with the exception of paroxetine (category D) and bupropion (category B), with slight variations between the medications’ safety in lactating mothers (NIMH, 2016).

In 2004, the FDA required a warning to be printed on the labels of all antidepressant medications regarding the risk for increased suicidality among children and adolescents taking these medications. The warning was expanded a few years later to include all young adults, especially those under the age of 25, stating that these individuals may experience an increase in suicidal thoughts or behaviors during the first few weeks of taking an antidepressant and warning clinicians to monitor patients for this effect. The FDA also requires manufacturers to provide a Patient Medication Guide (MedGuide), which is given to patients receiving these medications to advise them of the risks and precautions that can be taken to reduce the risk for suicide. Further, clinicians are advised to ask patients about suicidal thoughts prior to prescribing antidepressants to young persons (FDA, 2018). Table 2 provides a list of the points that must be included in the boxed warning.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are usually the safest initial choice and cause the least side effects. SSRIs include drugs such as citalopram (Celexa), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac), fluvoxamine (Luvox CR), paroxetine (Paxil), and sertraline (Zoloft) (Mayo Clinic, 2019b). Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) include duloxetine (Cymbalta), venlafaxine (Effexor), desvenlafaxine (Pristiq), and levomilnacipran (Fetzima). Both SSRIs and SNRIs can increase the levels of serotonin in the body, posing the risk for serotonin syndrome, which is a condition characterized by agitation, anxiety, confusion, high fever, sweating, tremors, lack of coordination, dangerous fluctuations in blood pressure, and rapid heart rate. Serotonin syndrome is a potentially life-threatening condition for which patients must seek immediate medical attention (Mayo Clinic, 2019c). Tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are an older class of medications including amitriptyline (Elavil), nortriptyline (Pamelor), clomipramine (Anafranil), imipramine (Tofranil), and desipramine (Norpramin). They also inhibit norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake, but with significantly more adverse effects than SSRIs or SNRIs, as outlined in Table 3 (Mayo Clinic, 2019d). The 2015 American Geriatric Society Beers Criteria (BC) of potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults publishes medications that should be avoided in older patients (65 years and older). The most recent version suggests that TCAs be avoided due to anticholinergic effects (Terrery, 2016).

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) were the first type of antidepressant medications developed. They impair the metabolism of serotonin and block monoamine oxidase, an enzyme that breaks down excess tyramine in the body. Tyramine is an amino acid that helps regulate blood pressure and is found naturally in the body, as well as in certain foods. MAOIs include tranylcypromine (Parnate), phenelzine (Nardil), isocarboxazid (Marplan), and a transdermal skin patch, selegiline (Emsam). Due to the risk for serious adverse effects, the use of MAOIs for the treatment of depression is generally reserved for patients who have failed all other treatment options. MAOIs have dangerous drug and food interactions. In particular, clinicians must warn patients on avoiding foods containing high levels of tyramine, such as aged cheese (aged cheddar, swiss, parmesan, and blue cheeses); cured, smoked or processed meats (pepperoni, salami, hotdogs, bologna, bacon, cored beef, smoked fish); pickled or fermented foods (sauerkraut, kimchi, tofu); sauces (soy sauce, miso and teriyaki sauce); soybean products; and alcoholic beverages (beer, red wine, liquors) (Mayo Clinic, 2018c, 2019a).

While antidepressants typically do not require routine laboratory monitoring or drug levels, prescribers should remain alert to the potential side effects and adverse effects outlined in Table 3 above. Further SSRIs are rarely associated with hyponatremia, bleeding, and decline in bone density. Prescribers should perform routine evaluation of patients on SSRIs and should consider ordering laboratory testing to evaluate for hyponatremia if patients experience any of the following rare, but possible medical complications associated. Bleeding events in patients on SSRI therapy most commonly present as GI bleeding, although this is rare. Patients who are prescribed venlafaxine XR (Effexor XR) should have their blood pressure checked at baseline and then periodically after starting and following any dose increase to evaluate for hypertension. The risk for hypertension with this medication is dose-dependent, and heightens with dose levels of 225mg or higher. Patients taking duloxetine (Cymbalta) should have their liver function tests evaluated about once annually due to low risk of alanine transaminase levels. Prior to prescribing TCAs, patients should be evaluated for the presence of any cardiac history and a baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) should be performed. ECG should be performed again once the therapeutic dose is achieved (Terrery, 2016).

There are also a few uncategorized atypical antidepressants, which differ from other classes of antidepressants and have varying mechanisms of action. As described above, bupropion (Wellbutrin) is an atypical antidepressant that works by inhibiting the reuptake of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. It is prescribed for depression as well as seasonal affective disorder and smoking cessation. As noted earlier, it may also be used off label for ADHD. Bupropion (Wellbutrin) is one of the few antidepressants that is not frequently associated with sexual dysfunction, though poses a risk for seizures, so use should be avoided in patients with preexisting seizure disorders. Adverse effects include hypertension, activation of mania or hypomania, and angle-closure glaucoma (FDA, 2017). Mirtazapine (Remeron) is an atypical tetracyclic antidepressant that antagonizes alpha-2 adrenergic and serotonin receptors. It can cause increased cholesterol and triglyceride levels, as well as sedation. Patients should be advised to take the medication prior to bedtime to avoid daytime sleepiness and drowsiness, particularly if operating a vehicle or heavy machinery. A rare but serious side effect of mirtazapine (Remeron) includes angle-closure glaucoma. Patients should be advised to report any eye pain, vision changes, as well as swelling or redness in or around the eye. Mirtazapine (Remeron) should not be taken within two weeks of taking an MAOI due to heightened risk for serotonin syndrome (National Alliance on Mental Illness [NAMI], 2018). Reboxetine (Edronax) is one of the most controversial antidepressants and has never been approved for use within the US. It selectively inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine, and while its use has been well documented in animal studies, it has failed in human studies. However, there is speculation that drug companies made the drug appear more effective than it actually is (Rajput, 2020).

Trazodone (Desyrel) is an antidepressant that works by inhibiting both serotonin transporters and serotonin type 2 receptors. It inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and blocks the histamine and alpha-1-adrenergic receptors. It is usually prescribed for depression when other medications have failed. Trazodone (Desyrel) should not be used in patients being treated with MAOIs, linezolid (Zyvox), methylene blue (ProvayBlue), the narcotic fentanyl (Duragesic), or in conjunction with any other serotonergic drugs, such as TCAs, due to heightened risk for serotonin syndrome. Clinicians must ensure that MAOIs are discontinued at least 14 days prior to starting trazodone (Desyrel). Patients should be advised to take the medication in the evening, prior to bedtime due to known drowsiness and sedation. Rare adverse effects include priapism (persistent and painful erection that is not associated with sexual arousal) and cardiac arrhythmias (Shin & Saadabadi, 2019). Vortioxetine (Trintellix) is a newer medication for depression that works by inhibiting serotonin reuptake, but also as a mixed antagonist/agonist of specific serotonin receptors. Vilazodone (Viibryd) acts as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, as well as a partial serotonin receptor agonist (NIMH, 2016).

Anxiety

Anxiety is a term that encompasses many different disorders, but all linked by the common thread of fear, worry, or concern that interferes with daily functioning and/or performance. Variations include:

- Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is characterized by excessive anxiety/worry about a number of various things, most days, for at least six months;

- Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is characterized by a general intense fear of social or performance situations;

- Panic disorder is characterized by sudden, recurrent, and unexpected periods of intense fear called panic attacks;

- Phobia-related disorders is characterized by an extreme fear or irrational aversion to something, such as agoraphobia (a fear of being out in public), or a fear of heights/flying, needles, blood, spiders, certain animals, and so forth;

- Separation anxiety disorder is characterized by a fear of being separated from the person/people to whom they are attached;

- Selective mutism is a condition typically seen in children under five who are unable to speak in certain social situations despite having normal language skills otherwise (NIMH, 2018a).

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic condition characterized by reoccurring and repetitive thoughts (obsessions) and behaviors (compulsions) that interfere with all aspects of life (NIMH, 2019b).

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a condition of significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning for more than one month after exposure to a traumatic event, defined as an event in which an individual has been personally or indirectly exposed to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence (US Department of Veterans Affairs [VA], 2017).

Both environmental and genetic influences can contribute to anxiety disorders, and risk factors include childhood shyness, stress buildup, certain personality types, exposure to stressful or traumatic life events when young, comorbid psychological conditions, drug/alcohol use, and biological relatives with anxiety disorders. Additionally, anxiety may be linked to an ongoing medical/health issue such as diabetes, heart disease, thyroid dysfunction, respiratory disorders, drug misuse, alcohol or drug withdrawal, chronic pain, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and rare tumors that produce hormonal imbalances. The gold standard treatment for anxiety, similar to depression, is often a combination of psychotherapy (cognitive or exposure therapy) and medications. Other adjunctive treatments that many patients with anxiety find helpful include support groups/chat rooms, stress management techniques (such as exercise), meditation, and mindfulness (Mayo Clinic, 2018a; NIMH, 2018a).

With regard to pharmacological therapy for the treatment of anxiety, benzodiazepines are among some of the most commonly used medications for the immediate and short-term relief of acute symptoms of anxiety. Benzodiazepines work by enhancing the effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the brain and can be used as a first line for GAD but are considered second line treatment for panic disorder and SAD behind antidepressants (NIMH, 2016). They promote relaxation and alleviate muscular tension and other physical symptoms of anxiety. The most commonly used benzodiazepines include clonazepam (Klonopin), alprazolam (Xanax), diazepam (Valium), and lorazepam (Ativan). These agents are also frequently used for short-term management of anxiety, such as for minor medical procedures. While benzodiazepines have the advantage of a very fast onset of action and are highly effective in alleviating acute symptoms, they are schedule IV controlled substances according to the DEA. In some states they are classified as schedule II due to high risk of abuse and dependence. Benzodiazepines also carry a high risk of tolerance, and can cause withdrawal symptoms if abruptly discontinued, so they should be tapered slowly and carefully. Additional adverse effects of benzodiazepine include drowsiness or tiredness, dizziness, nausea, blurred vision, headache, confusion, and nightmares (NIMH, 2016). For this and other reasons, benzodiazepines are often considered second line for chronic anxiety behind antidepressants or used on an as-needed basis for break through symptoms. Most benzodiazepines were previously categorized by the FDA as pregnancy category D or X (positive evidence of risk), and women of childbearing age should be counseled extensively on their individual risk prior to starting a benzodiazepine (NIMH, 2018a). The most recent version of the BC recommends that benzodiazepines be avoided in older patients for insomnia, agitation, or delirium due to fall risk and high rate of physical dependence, especially longer acting versions (Terrery, 2016).

Buspirone (Buspar) is approved for the treatment of chronic anxiety, but it is not a benzodiazepine and is not a controlled substance. It works by binding to serotonin and dopamine D2 receptors. Unfortunately, it does not work for everyone, and needs to be taken every day as it does not work when taken on an as-needed basis. Adverse effects of buspirone (Buspar) include dizziness, headache, nausea, nervousness, lightheadedness, excitement, and trouble sleeping, and was categorized by the FDA as pregnancy category B (no evidence of risk). Beta blockers can be given to help alleviate the physical symptoms of anxiety such as sweating, trembling, and tachycardia during especially stressful events, such as large social gatherings, weddings, or public speaking engagements. They can be taken as-needed, but can cause hypotension, bradycardia, dizziness, weakness, fatigue, and cold hands and are not recommended for diabetics and asthmatics. Antidepressants such as SSRIs and SNRIs (see above) are now more commonly being used as a first line treatment for chronic anxiety conditions (NIMH, 2016).

In patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), trauma focused psychotherapy is considered first-line treatment, while SSRIs including sertraline (Zoloft), paroxetine (Paxil), and fluoxetine (Prozac), and the SNRI venlafaxine (Effexor) are the most commonly used medications in refractory cases; although only sertraline (Zoloft) and paroxetine (Paxil) have been FDA approved for this indication (VA, 2017). OCD is often treated with a combination of psychotherapy and medications, the most common of which are clomipramine (Anafranil), fluoxetine (Prozac), fluvoxamine (Luvox CR), and sertraline (Zoloft). These medications will typically take 8-12 weeks to show improvement in symptoms in patients with OCD, and usually require dose levels that are significantly higher than when used for depression (NIMH, 2019b).

Bipolar Disorder

Formerly manic depression, bipolar disorder is characterized by extreme mood swings between manic periods of elevated or irritable mood, over-activity, racing thoughts, pressure of speech, inflated self-esteem, and decreased need for sleep, usually interspersed with depressed periods. According to the WHO (2019), bipolar disorder effects around 60 million people worldwide. There are currently four classifications:

- Bipolar disorder I (BDI): manic episodes lasting at least seven days and often requiring hospitalization, interspersed with depressive episodes usually lasting at least two weeks;

- Bipolar disorder II (BDII): typically longer-lasting depressive episodes separated by periods of hypomania lasting at least four days (similar to manic episodes but less severe, without psychosis or the need for hospitalization);

- Cyclothymic disorder/cyclothymia: numerous periods of hypomanic and depressive symptoms, alternating for at least two years, but not severe enough to meet the above diagnostic criteria for bipolar II;

- Other: bipolar disorder symptoms that do not match any of the above three categories, such as symptoms induced by substance abuse or caused by certain medical conditions such as Cushing’s disease, multiple sclerosis (MS), or stroke (Mayo Clinic, 2018b).

While the exact cause of bipolar disorder is still unknown, most scientists believe it is some combination of altered brain structure/function, genetics, and environmental factors. Patients with bipolar disorder are at higher risk for thyroid disease, migraines, heart disease, diabetes, obesity and other physical illnesses as well as anxiety, ADHD, and substance abuse. Symptoms of a depressive episode match the aforementioned symptoms of depression above. Behavior seen in a manic episode may include the previously mentioned symptoms as well as disorganized or nonlinear patterns of thoughts/speech and risk-taking behaviors such as spending frivolously or sexual promiscuity. Hypomanic episodes may present as the individual feeling very good, being highly productive, and functioning well. Hypomania may develop into full mania if untreated. Some patients with bipolar disorder may also suffer from psychotic features, such as delusions or hallucinations (Mayo Clinic, 2018b; NIMH, 2016).

Risk factors include a first degree relative with bipolar disorder, a stressful or traumatic life event, and drug or alcohol use. It is most commonly diagnosed in the teenage years or early 20’s, and if left untreated can lead to drug/alcohol abuse, legal or financial problems, damaged relationships, poor work/school performance, or suicide. Estimates are that 6-7% of bipolar patients die by suicide, and up to 43% of patients with bipolar disorder report suicidal ideations (Yatham et al., 2018). Bipolar disorder is a lifelong illness and requires consistent and regular treatment with psychotherapy and medications to manage symptoms long term. Psychotherapy may consist of CBT, family-focused therapy, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, and/or psychoeducation and in severe cases may require ECT (Mayo Clinic, 2018b).

Medications for bipolar disorder may include mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotics, antidepressants, sleep medications, and/or supplements. Lithium (Lithobid), a commonly prescribed mood stabilizer that works by altering sodium transport across neurons, has been approved for the treatment of acute mania and the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder (NIMH, 2016). According to the International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD), lithium (Lithobid) alone is recommended as first-line treatment for acute mania and maintenance therapy of BDI based on level 1 evidence. Based on level 2 evidence it is considered first-line treatment for acute depression in BDI, first-line for maintenance treatment in BDII, and second line for acute depression treatment in BDII. There is moderate concern about safety and tolerability with lithium (Lithobid) use long term as it is considered possibly hazardous in breastfeeding moms (Yatham et al, 2018). Alternatives for mood stabilization include anticonvulsants such as divalproex sodium (Depakote), valproic acid (Depakene), carbamazepine (Tegretol), and lamotrigine (Lamictal) (NIMH, 2016). Divalproex sodium (Depakote) is first-line monotherapy for acute mania and maintenance therapy of BDI based on level 1 evidence, second-line for acute depressive episodes in BDI based on level 2 evidence, third-line for maintenance treatment in BDII based on level 3 evidence, and third-line for acute depression treatment in BDII based on level 4 evidence. Carbamazepine (Tegretol) is considered second line treatment in acute mania based on level 1 evidence, and can be used for maintenance treatment, but it is considered second line treatment for BDI based on level 2 evidence, and third line treatment for BDII based on level 3 evidence. Lamotrigine (Lamictal) is not recommended for acute mania. It is considered a first-line treatment for maintenance therapy of BDI based on level 1 evidence, and based on level 2 evidence it is considered first line treatment for acute depression in BDI, second line for acute depression in BDII, and first line for BDII maintenance treatment (Yatham et al., 2018).

Regarding safety and tolerability for long term use, divalproex sodium (Depakote) has moderate safety and minor tolerability concerns, and carbamazepine (Tegretol) has minor safety and moderate tolerability concerns, while lamotrigine (Lamictal) has very limited safety or tolerability concerns. The disadvantages of most mood stabilizers include their renal toxicity and the need for initial serum drug levels to be monitored until dosing is stable, and then periodically to rule out toxicity (this is true for lithium [Lithobid], divalproex sodium [Depakote], and carbamazepine [Tegretol]). Mood stabilizers are also associated with several adverse effects including:

- Itching, rash;

- Excessive thirst;

- Frequent urination;

- Tremors;

- Nausea and vomiting;

- Slurred speech;

- Fast, slow, irregular, or pounding heartbeat;

- Blackouts (loss of consciousness);

- Changes in vision;

- Seizures;

- Hallucinations;

- Loss of coordination;

- Swelling of the eyes, face, lips, tongue, throat, hands, feet, ankles, or lower legs (NIMH, 2016)

Patients who are taking mood stabilizers should have specific monitoring based on the medication prescribed. Those on Lithium (Lithobid) should have serum lithium levels evaluated following one week of therapy, following all dose adjustments, in the presence of any concerning side effects, and annually. They should also have their thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) checked at baseline, two weeks, six weeks, and then annually. The renal function should be evaluated at baseline, two weeks, and then annually. Patients who are prescribed valproic acid (Depakote) should have serum levels evaluated one week of therapy, following all dose adjustments, in the presence of any concerning side effects, and annually. In addition, they should have their liver function tests (LFTs) checked at baseline, two weeks, and annually, as well as if any symptoms or clinical suspicion for hepatitis develops. The complete blood count (CBC) should be evaluated after two weeks, six months, and then annually, unless the patient develops any signs of easy bruising or bleeding; which should prompt additional CBC testing. For patients taking carbamazepine (Tegretol), serum drug levels should be monitored at one week, four weeks, annually, and with any dose increases. These patients should have CBC checked at one week, one month, four months, and annually. Sodium level should be checked at one week and then annually, and LFTs should be checked at two weeks and annually. With oxycarbazepine (Trileptal), patients should their sodium level checked at baseline and at one month. Patients on lamotrigine (Lamictal) do not require any laboratory monitoring (How & Xiong, 2019).

Atypical (or second-generation) antipsychotics help treat the symptoms of agitation, delusions, and hallucinations that are often seen in bipolar disorder. This may include medications such as quetiapine (Seroquel), asenapine (Saphris), aripiprazole (Abilify), paliperidone (Invega), risperidone (Risperdal), olanzapine (Zyprexa), ziprasidone (Geodon), cariprazine (Vraylar), clozapine (Clozaril) and lurasidone (Latuda). These drugs function mostly by antagonizing dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in the brain, except for aripiprazole (Abilify) and cariprazine (Vraylar), which function as partial dopamine and serotonin 5-HT1A agonists and 5-HT2A antagonists (NIMH, 2016). As a class, adverse effects for this group of drugs may include drowsiness, dizziness, restlessness, weight gain, anticholinergic effects, nausea/vomiting, hypotension, seizures, and leukocytopenia (NIMH, 2016). Antipsychotics will be discussed in greater depth within the next section on schizophrenia and psychosis.

According to the ISBD, there is level 1 evidence to support the use quetiapine (Seroquel), asenapine (Saphris), aripiprazole (Abilify), paliperidone (Invega), risperidone (Risperdal), and cariprazine (Vraylar) for the treatment of acute mania. It is estimated that as many as 50% of patients will significantly improve with monotherapy in three to four weeks, but combination therapy increases this by about 20% and may be beneficial in patients with a history of partial response to monotherapy, with psychotic mania, or where rapid response is desired. In those cases, there is level 1 evidence supporting the combination of lithium (Lithobid) or divalproex sodium (Depakote) combined with quetiapine (Seroquel) or risperidone (Risperdal) for acute mania. There is level 2 evidence supporting lithium (Lithobid) or divalproex sodium (Depakote) combined with aripiprazole (Abilify) or asenapine (Saphris) for acute mania. There is level 1 evidence supporting the use of olanzapine (Zyprexa) (alone or with lithium [Lithobid]/divalproex sodium [Depakote]), carbamazepine (Tegretol), or ziprasidone (Geodon) as second line treatments for acute mania. In the treatment of acute depression in BDI, there is level 1 evidence supporting the use of quetiapine (Seroquel), or a combination of lurasidone (Latuda) and lithium (Lithobid)/divalproex sodium (Depakote), as first line treatments, and level 2 evidence supporting the use of lurasidone (Latuda) alone. Olanzapine (Zyprexa) also has level 1 evidence as a second-line treatment for acute depression in BDI (Yatham et al., 2018).

Regarding maintenance or long-term therapy, there is level 1 evidence to support using quetiapine (Seroquel) (alone or with lithium [Lithobid]/divalproex sodium [Depakote]), and level 2 evidence for the use of asenapine (Saphris), aripiprazole (Abilify) (alone or combined with lithium [Lithobid] or divalproex sodium [Depakote]) as first line treatment options in BDI. There is also level 1 evidence supporting the use of olanzapine (Zyprexa) or risperidone (Risperdal) as second line maintenance treatment options in BDI. In BDII, there is level 1 evidence supporting the use of quetiapine (Seroquel) as a first line treatment for acute depression or long-term maintenance therapy. Third line treatment options for long-term maintenance treatment of BDII include carbamazepine (Tegretol) (based on level 3 evidence) or risperidone (Risperdal) (based on level 4 evidence, primarily to prevent hypomania episodes). Regarding safety and tolerability, there are more concerns with olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine (Seroquel), and risperidone (Risperdal) than the other atypical antipsychotics discussed here, especially when combined with lithium (Lithobid) or divalproex sodium (Depakote)(Yatham et al., 2018).

SSRIs, SNRIs, and bupropion (Wellbutrin) are sometimes used for acute depressive symptom management in bipolar disorder. According to the ISBD, these drugs should not be used as monotherapy in patients with bipolar disorder I acute depression. However, in patients with BDI there is level 1 evidence supporting their use as second line adjunctive therapy (with lithium [Lithobid], divalproex sodium [Depakote], or an atypical antipsychotic) for acute depression, and level 4 evidence supporting their long-term use for prevention of depressive episodes. In patients with BDII, there is level 2 evidence suggesting bupropion (as an adjunct), sertraline (Zoloft), or Venlafaxine (Effexor) are appropriate second line treatment adjuncts for acute pure (non-mixed) depression, and third line options include agomelatine (based on level 4 evidence) or fluoxetine (Prozac) (based on level 3 evidence). For long-term maintenance therapy in patients with BDII, there is level 2 evidence supporting the use of venlafaxine (Effexor) as a second line treatment, and level 3 evidence of the use of escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac) or other antidepressants as third line treatment options only. Antidepressants should be avoided in patients with a history of antidepressant-induced mania/hypomania, current or predominantly mixed features, or recent rapid cycling. TCAs should be avoided in patients with BDI due to increased risk for mania, but the MAOI tranylcypromine (Parnate) was recommended as a third-line treatment option for acute depression in BDII based on level 3 evidence. Benzodiazepines have not been shown to provoke mood instability in patients with bipolar disorder, so for comorbid anxiety or difficulty with sleep, lorazepam (Ativan), clonazepam (Klonopin), or similar could be considered as a short-term alternative, although no long-term studies exist to confirm this (Yatham et al, 2018).

Schizophrenia/Psychosis

According to the WHO, there are approximately 20 million people affected by schizophrenia worldwide. This severe mental disorder typically begins in late adolescence or early adulthood and is characterized by psychoses or distortions in thinking, perception, emotions, language, behavior or sense of self (WHO, 2019). Symptoms are categorized as positive (hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thoughts/speech, movement disorders), negative (flat affect, loss of pleasure in everyday life, difficulty beginning/sustaining activities, reduced speaking) or cognitive (poor executive functioning, decreased focus/attention, poor working memory). Genetic predisposition along with potential environmental triggers such as viruses, prenatal malnutrition, problems during birth, and psychosocial factors likely combine to cause or increase the risk for schizophrenia. Alterations in brain structure and chemistry (especially the neurotransmitters dopamine and glutamate) also play a role (NIMH, 2016). According to the Mayo Clinic (2020), risk factors for schizophrenia include a family history, pregnancy and birth complications such as malnutrition or exposure to toxins or viruses in utero that impair brain development, and exposure to psychotropic drugs during adolescence/young adulthood. Common complications of schizophrenia include self-injury, anxiety, depression, OCD, alcohol or substance abuse, social isolation, inability to work or attend school, medical or health problems, legal and financial problems, homelessness, aggressive behavior, suicide, suicide attempts, and thoughts of suicide (Mayo Clinic, 2020).

Treatment for schizophrenia is multifactorial and lifelong and includes pharmacological management in combination with psychosocial support. A psychiatrist usually guides treatment and due to the complexity of the diagnosis, coordinated specialty care (CSC) is recommended. CSC refers to a team approach involving case managers, family, social workers, in addition to educational and employment service involvement. CSC has been shown to be especially helpful in patients with schizophrenia at reducing symptoms, improving quality of life, increasing compliance with medication therapy, and enhancing outcomes (NIMH, 2016). Pharmacotherapy includes management of the acute phase followed by maintenance therapy, which strives to improve socialization, self-care, and mood. The rationale for maintenance treatment is to prevent relapse. The goal of medication use is to manage signs and symptoms using the lowest effective dosage and the least amount of side effects possible. In many cases, combination therapy with multiple medications is necessary to gain adequate control over the condition. Identifying the proper medication combination and dosing levels can take time to achieve the desired outcome. While it can take several weeks to notice an improvement in symptoms, prompt initiation of medication therapy within five years of the first acute episode is recommended; this is the time period in which most of the illness-related changes in the brain occur (Freudenreich & McEvoy, 2018).

According to the APA (2019) practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, which are currently available online as a 2019 draft version (final revisions are expected to be published in the summer of 2020), second-generation antipsychotic (SGAs or atypical) medications are a newer class of antipsychotic drugs that are considered first-line treatment. These drugs are thought to help control symptoms by affecting the abnormal dopamine levels in the brain noted in patients with schizophrenia. While the selection of the type of antipsychotic agent depends on various individual patient factors, SGAs are generally preferred over first-generation (FGAs or typical) antipsychotics due to their superior side effect profile. The APA guideline also acknowledges that an evidence-based algorithm approach to antipsychotic selection is not available due to limitations in clinical trial designs and lack of direct drug-to-drug comparisons. Currently, “there is no definitive evidence that one antipsychotic will have consistently superior efficacy compared with another, with the possible exception of clozapine (Clozaril)” (APA, 2019, p. 52). Clozapine (Clozaril) is the only medication within the class of SGAs that is not recommended as first-line treatment as it carries a risk for life-threatening agranulocytosis, which is a decline in the white blood cell level, namely the absolute neutrophil count (ANC). Clozapine (Clozaril) is reserved for patients who are resistant to treatment with other antipsychotic drugs, as it is considered the most effective antipsychotic drug for the management of treatment-resistant schizophrenia (Freudenreich & McEvoy, 2018).

The APA guideline recommends that drug selection is premised on the risks and benefits of the prescribed therapy, individual patient factors such as co-existing medical conditions, the potential for those conditions to be affected by medication side effects, risk for drug interactions, psychosocial support, patient and family preference, as well as the feasibility of compliance with chosen therapy. Prior to starting antipsychotic therapy, the clinician is advised to obtain a complete and thorough medication history, reviewing current medications, any prior antipsychotic medications used in the past, and the patient’s tolerance to treatment. It is critical to assess for any drug allergies, medication interactions, or contraindications to drug therapy. Clinicians must also assess the potential benefits of treatment as well as the potential harms of untreated illness with regards to the potential for negative fetal or neonatal effects in females of childbearing age. Untreated or inadequately treated maternal psychiatric illness can result in poor adherence to prenatal care, inadequate nutrition, increased alcohol or tobacco use, and disruptions to the family environment and mother–infant bonding. In addition, all psychotropic medications appear to cross the placenta, have been found in amniotic fluid, and in human breast milk (APA, 2019).

FGAs and SGAs are available in short-acting/IR and ER oral (po) formulations, as well as short-acting intramuscular (IM) and long-acting injectable (LAI) agents. LAI medications are a practical option for patients who are noncompliant with oral medication therapy. However, clinicians are advised to first determine the etiology of the patient’s noncompliance with oral treatment prior to changing to LAI. If nonadherence is related to undesirable adverse effects of oral treatment, then the patient should first be changed to an alternative oral medication prior to transitioning to LAI (APA, 2019). When starting antipsychotic medications, clinicians are advised to start at the lowest dose possible and gradually increase the medication dose, as recommended by the individual drug’s prescribing guidelines. Agitation and hallucinations typically resolve first (within days) but delusions may take weeks to resolve, and full effects are usually seen by six weeks (NIMH, 2016). Some antipsychotic medications require strict monitoring as outlined by the FDA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) drug program, which is reserved for drugs with serious safety concerns to help ensure the benefits of the medication outweigh the risks. REMS is designed to mitigate the occurrence and severity of certain risks by enhancing the safe use of high-risk medication as described within the FDA-approved prescribing information, through the heightened monitoring and surveillance of patients receiving these medications (FDA, 2019).

First-Generation Antipsychotics

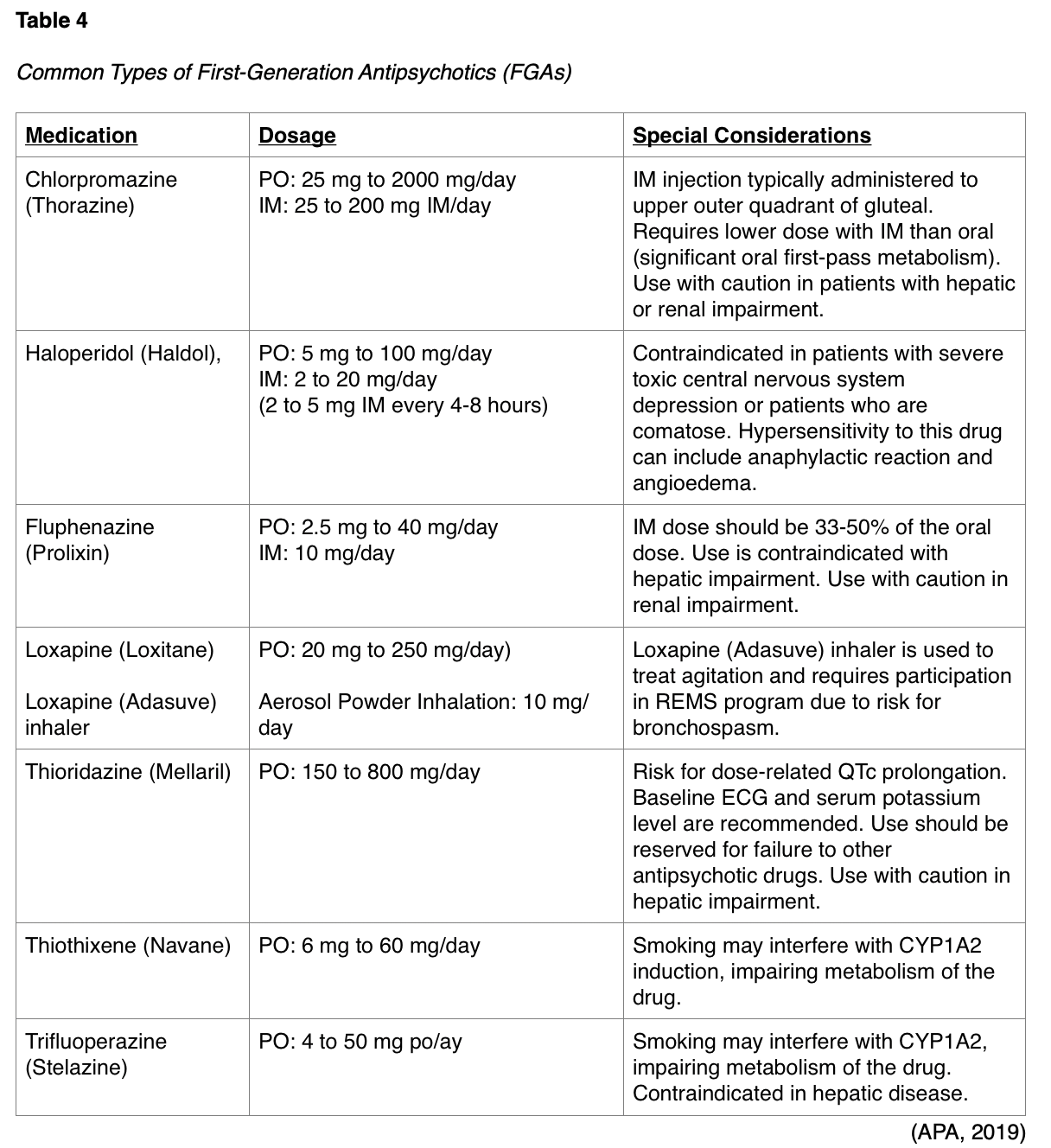

FGAs work by antagonizing dopamine D2 receptors and some of the most common include chlorpromazine (Thorazine), haloperidol (Haldol), fluphenazine (Prolixin), loxapine (Loxitane), molindone (Moban), perphenazine (Trilafon), thioridazine (Mellaril), thiothixene (Navane), and thrifluoperazine (Stelazine). FGAs pose the highest risk for extrapyramidal symptoms (EPSs) among all antipsychotic medications. EPSs are drug-induced movement disorders that are one of the most common adverse effects from centrally acting, dopamine-receptor blocking medications. EPSs are often debilitating and interfere with communication, socialization, motor skills, and activities of daily living. These symptoms can include acute dystonia (spasm of the tongue, neck, face, and back), Parkinsonism (tremor, shuffling gait, drooling, instability, stooped posture), akathisia (compulsive and repetitive motions, agitation), and tardive dyskinesia (lip smacking, worm-like tongue movements). Other less common but potential side effects of FGAs can include orthostasis, QT prolongation, weight gain, seizures, hyperlipidemia, and glucose abnormalities (D’Souza & Hooten, 2019). Refer to Table 4 for a detailed overview of dosing and special conditions of several types of FGAs

Second-Generation Antipsychotics

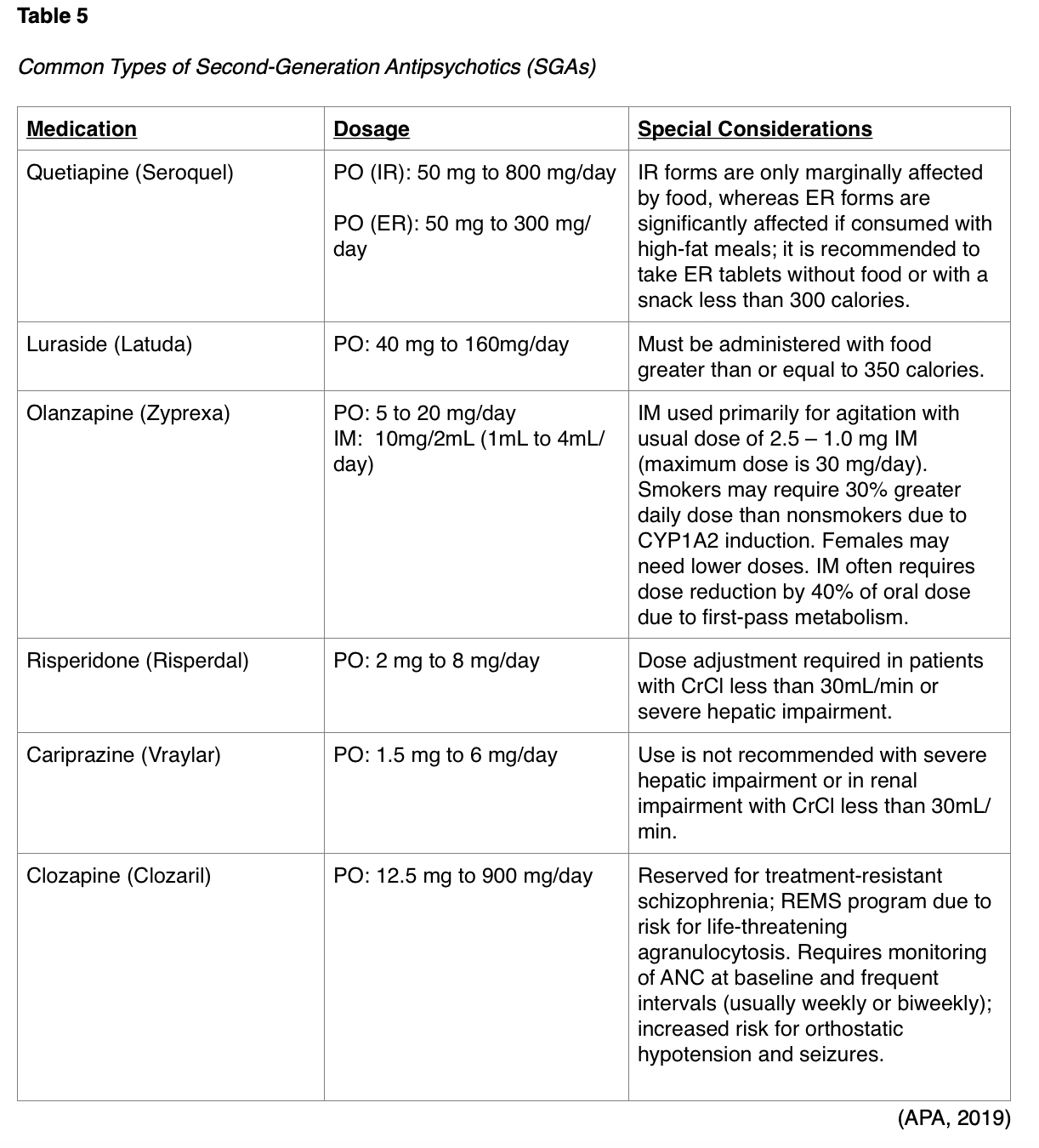

SGAs include medications such as quetiapine (Seroquel), asenapine (Saphris), aripiprazole (Abilify), brexpiprazole (Rexulti), paliperidone (Invega), risperidone (Risperdal), olanzapine (Zyprexa), ziprasidone (Geodon), cariprazine (Vraylar), lurasidone (Latuda), and clozapine (Clozaril). SGAs work by antagonizing dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in the brain, except for aripiprazole (Abilify) and cariprazine (Vraylar), which function as partial dopamine and serotonin 5-HT1A agonists and 5-HT2A antagonists. Clozapine (Clozaril) also functions differently as it antagonizes alpha adrenergic and cholinergic muscarinic receptors. Some of the most common SGAs are outlined in Table 5. EPSs occur less frequently with SGAs than with FGAs; however, EPS risk increases with dose escalation. As a class, SGAs pose risk for metabolic side effects, such as weight gain, hyperlipidemia, seizures, and diabetes mellitus, which can thereby contribute to the increased risk of cardiovascular mortality in schizophrenic patients. Less commonly, SGAs can cause orthostasis and QT prolongation (D’Souza & Hooten, 2019). According to the most recent BC, antipsychotic drugs should be avoided as a first line treatment for delirium in older patients unless they are a threat to self or others due to increased risk of stroke and mortality in the elderly with dementia and olanzapine (Zyprexa) syncope (Terrery, 2016).

Monitoring of Patients on Antipsychotics

While there are several important monitoring domains required for patients on antipsychotic medications, adherence is one of the most common problems that impairs effective outcomes. Monitoring for the presence of side effects is essential, as undesirable side effects are most commonly associated with treatment nonadherence and treatment discontinuation. Some side effects of treatment will improve over time, whereas others may worsen with dose escalation. In general, early in the course of treatment, the most common side effects include sedation, fatigue, orthostatic hypotension, and anticholinergic effects such as dry mouth, constipation, and difficulty urinating. As treatment progresses, many of these side effects dissipate or improve. In contrast, side effects corresponding with metabolic syndrome such as weight gain, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia worsen throughout the duration of therapy. Furthermore, EPSs can also worsen with dose escalation of antipsychotics, particularly FGAs. All types of antipsychotic are associated with sexual dysfunction which can include loss of libido, anorgasmia, erectile dysfunction, and ejaculatory disturbances such as retrograde ejaculation (APA, 2019).

As recommended by consensus guidelines put forth by the American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists in 2004, patients on SGAs should undergo the following monitoring parameters at baseline and at follow up visits as specified below.

- Personal and family history of obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease (baseline and annually);

- Weight and height, or BMI (baseline, four weeks, eight weeks, 12 weeks, quarterly, and annually);

- Waist circumference (baseline and annually);

- Blood pressure (baseline, 12 weeks, and annually);

- Fasting plasma glucose (baseline, 12 weeks, and annually);

- Fasting lipid profile (baseline, 12 weeks, and annually) (American Diabetes Association, 2004; Magellan Health, 2014).

The APA (2019) pharmacotherapy treatment guideline recommends that patients with schizophrenia:

- be treated with an antipsychotic medication and monitored for effectiveness and side effects;

- whose symptoms have improved with an antipsychotic medication continue to be treated with an antipsychotic medication;

- who are treatment-resistant be treated with clozapine (Clozaril);

- be treated with clozapine (Clozaril) if the risk for suicide attempts or suicide remains substantial despite other treatments;

- be treated with clozapine (Clozaril) if the risk for aggressive behavior remains substantial despite other treatments;

- receive treatment with an LAI antipsychotic medication if they prefer such treatment or if they have a history of poor or uncertain adherence;

- who have acute dystonia associated with antipsychotic therapy be treated with an anticholinergic medication;

- who have parkinsonism associated with antipsychotic therapy, be prescribed a lower dosage of the antipsychotic medication, be switched to another antipsychotic medication, or be treated with an anticholinergic medication to offset the parkinsonism;

- who have akathisia associated with antipsychotic therapy, be prescribed a lower dosage of the antipsychotic medication, be switched to another antipsychotic medication, be prescribed a benzodiazepine medication, or a beta- adrenergic blocking agent to offset the parkinsonism; and

- who have moderate to severe or disabling tardive dyskinesia associated with antipsychotic therapy be treated with a reversible inhibitor of the vesicular monoamine transporter2 (VMAT2) (APA, 2019, p. 16-17).

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2019). Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 144(4), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2528

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2020). Amphetamine - adderall. https://www.aap.org/en-us/professional-resources/Psychopharmacology/Pages/Amphetamine-Adderall.aspx

American Diabetes Association. (2004). Consensus statement: Consensus development of conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes care, 27(2), 596- 601. https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/diacare/27/2/596.full.pdf

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Association Publishing

American Psychiatric Association. (2019). The American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. (Draft 2019). https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/clinical-practice-guidelines

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Treatment of ADHD. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/treatment.html

Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. (n.d.). The role of medication. Retrieved March 1, 2020 from https://chadd.org/for-professionals/the-role-of-medication/

Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. (2017). About ADHD. https://chadd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/aboutADHD.pdf

Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. (2018). Understanding ADHD. http://www.chadd.org/Understanding-ADHD/For-Professionals/For-Healthcare-Professionals.aspx

D’Souza, R. S., & Hooten, W. M. (2019). Extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534115/

Freudenreich, O., & McEvoy, J. (2018). Guidelines for prescribing clozapine in schizophrenia. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/guidelines-for-prescribing-clozapine-in-schizophrenia

Goldberg, J. F. (2018). The Psychopharmacology of depression: Strategies, formulations, and future implications. Psychiatric Times, 35(7), 9-14. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/depression/psychopharmacology-depression-strategies-formulations-and-future-implications

How, P. C., & Xiong, G. (2019). Pharmacological overview in geriatrics: Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, laboratory monitoring. In H. H. Fenn, A. Hategan, & J. A. Bourgeois. (Eds.). Inpatient Geriatric Psychiatry: Optimum care, emerging limitations, and realistic goals (pp. 47-61). Springer Link.

Magellan Health. (2014). Second generation antipsychotic tip sheet. https://www.ibx.com/pdfs/providers/resources/worksheets/antipsychotic_tip_sheet.pdf

Mayo Clinic. (2018a). Anxiety disorders. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anxiety/symptoms-causes/syc-20350961

Mayo Clinic (2018b). Bipolar disorder. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/bipolar-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20355955

Mayo Clinic. (2018c). MAOIs and diet: Is it necessary to restrict tyramine? https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/expert-answers/maois/faq-20058035

Mayo Clinic. (2019a). Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/in-depth/maois/art-20043992

Mayo Clinic. (2019b). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/in-depth/ssris/art-20044825

Mayo Clinic. (2019c). Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/in-depth/antidepressants/art-20044970

Mayo Clinic. (2019d). Tricyclic antidepressants and tetracyclic antidepressants. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/in-depth/antidepressants/art-20046983

Mayo Clinic. (2020). Schizophrenia. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/schizophrenia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354443

National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2018). Mirtazapine (Remeron). https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Treatment/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Mirtazapine-(Remeron)

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. (2017). St. John’s wort and depression: In depth. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/stjohnswort/sjw-and-depression.htm

National Institute of Mental Health. (2016). Mental health medications. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/mental-health-medications/index.shtml#part_149857

National Institute of Mental Health. (2018a). Anxiety disorders. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders/index.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health. (2018b). Depression. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression/index.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health. (2019a). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/index.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health. (2019b). Obsessive-compulsive disorder. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/obsessive-compulsive-disorder-ocd/index.shtml

Rajput, K. (2020). Reboxetine (Edronax): The most controversial antidepressant. https://www.psycom.net/reboxetine-edronax

Shin, J. J., & Saadabai, A. (2019). Trazodone. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470560/

Tarraza, M., & Barry, L. (2017). Chapter 14. Integrative Management of disorders attention. In K. R. Tusaie & J. J. Fitzpatrick. (Eds.). Advanced practice psychiatric nursing: Integrating psychotherapy, psychopharmacology, and complementary and alternative approaches across the lifespan. (2nd ed.). Springer Publishing Company

Terrery, C. L., & Nicoteri, J. A. (2016). The 2015 American Geriatric Society Beers Criteria: Implications for nurse practitioners. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 12(3), 192-200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.11.027

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2017). VA/DOD clinical practice guideline for the management of post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal012418.pdf

US Food & Drug Administration. (2017). Wellbutrin® (bupropion hydrochloride) tablets – FDA. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/018644s052lbl.pdf

US Food & Drug Administration. (2018). Suicidality in children and adolescents being treated with antidepressant medications. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/suicidality-children-and-adolescents-being-treated-antidepressant-medications

US Food & Drug Administration. (2019). Risk evaluation and mitigation strategies / REMS. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/risk-evaluation-and-mitigation-strategies-rems

Whiting, P. F., Wolff, R. F., Deshpande, S., Nisio, M. D., Duffy, S., Hernandez, A. V., Keurentjes, J. C., Lang, S., Misso, K., Ryder, S., Schmidlkofer, S., Westwood, M., & Kleijnen, J. (2015). Cannabinoids for medical use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 313(24), 2456-2473. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.6358

World Health Organization. (2019). Mental disorders. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders

Yatham, L. N., Kennedy, S. H., Parikh, S. V., Schaffer, A., Bond, D. J., Frey, B. N., Sharma, V., Goldstein, B. I., Rej, S., Beaulieu, S., Alda, M., MacQueen, G., Milev, R. V., Ravindran, A., O’Donovan, C., McIntosh, D., Lam, R. W., Vasquez, G., Kapczinski, F., McIntyre, R. S., … Berk, M. (2018). Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) and international society for bipolar disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders, 20(2), 97-170. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12609