About this course:

The purpose of this module is to provide an overview of the most common mental illnesses affecting veterans and their families, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, grief, and suicide, by reviewing the defining characteristics of each condition, available screening methods, interventions, treatments, and resources.

Course preview

The purpose of this module is to provide an overview of the most common mental illnesses affecting veterans and their families, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, grief, and suicide, by reviewing the defining characteristics of each condition, available screening methods, interventions, treatments, and resources.

At the completion of this module, the learner should be able to:

- discuss the epidemiology of mental health in military veterans and their families in the US and military cultural competence

- review screening methods used to evaluate the most common mental health conditions affecting veterans and their family members

- summarize the diagnosis, symptoms, and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and grief

- review the impact of traumatic brain injury on normal functioning and treatment options

- outline the risk factors and warning signs of those at risk for suicide, discuss the core components of suicide prevention training, describe safety planning, and outline evidence-based tools and intervention

- identify available resources for veterans diagnosed with mental illness and their family members

Epidemiology

Current statistics indicate that there are 17.4 million living veterans in the US; among these, 15.8 million are male, and 1.6 million are female. According to the US Census Bureau (2020), the veteran population has declined by more than one-third since 2000, when there were 26.4 million living veterans. In addition, at least 1.3 million individuals currently serve in active duty across all branches of the military, with over 3 million immediate family members (Statista, 2020; US Census Bureau, 2020). Mental health is as critical as physical health; injury to the mind and spirit can lead to a loss of control and damage essential life functions. Veterans and their family members are more likely to suffer from mental health disorders than those who have never served in the armed forces. According to the most recent Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA, 2020a) National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 1 in 4 veterans have a serious mental illness, and 3.9 million veterans had a mental illness. Major depressive episodes were most common among female veterans aged 26 years and older (11.3%) and male veterans aged 18 to 25 (3.3%). Despite the significant consequences and disease burden associated with mental illness, SAMHSA has exposed tremendous treatment gaps among veterans. For example, no treatment was received by 53.3% of veterans with any mental illness (AMI) and 26.8% with serious mental illness (SMI; SAMHSA, 2020a). AMI includes all mental illnesses, and effects can range from no impairment to mild, moderate, or severe impairment. SMI is a smaller but more severe subset of AMI. For those with SMI, mental illness causes significant functional impairment and substantially interferes with at least one major life activity (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2021; SAMHSA, 2020a).

An estimated 2.77 million Americans have been deployed worldwide since the tragic events of 9/11/2001, and at least 793,000 service members have been deployed more than once (Statista, 2018). Nearly 20% of service members returning from deployment had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, or sustained a traumatic brain injury (TBI) during their combat duty. The impact of deployment; the demands, dangers, and traumas of combat; and the separation of families often provoke deep-rooted and ongoing challenges for veterans and their families. Over 1.7 million veterans received mental health services at a Veterans Administration Medical Center or Military Treatment Facility over the last year. However, the stigma regarding mental health is still evident within the military culture. Research demonstrates that many veterans view seeking mental health care as a weakness or fear that seeking help will interfere with their future military career or potential promotions. Regardless of the reason, many veterans opt to seek treatment in civilian environments, including hospitals, clinics, and primary care settings. Nurses of all educational backgrounds and licensures (i.e., LPNs, RNs, and APRNs) serve vital roles in dispelling the stigma and should engage with veterans without inadvertently reinforcing these misconceptions. All nurses must be prepared to care for military members and veterans across primary care, urgent care, emergency, and hospital settings. To care adequately and effectively for veterans and their families, nurses must receive knowledge and training on the unique challenges faced by these populations (SAMSHA, 2020; US Department of Veterans Affairs [VA], 2019b).

Screening Veterans & Family Members for Mental Health Conditions

Mental illnesses comprise several different conditions that vary in severity and range from mild to moderate to severe. They are often subject to periods of relapse but are treatable, and many veterans recover with symptoms managed and functioning restored. Veterans may not share information regarding their military service with health care professionals if they are not prompted to do so. Therefore, a core component of all health history-taking and clinical assessments is to ask, “Have you ever served in the military?” Family members may have also been impacted by military service and should be screened by asking, “Do you have a close family member who has served in the military?” The VA (2019b) suggests that all health care professionals should adhere to the following guidelines when inquiring about military health history:

- ask questions in a safe and private area

- maintain eye contact

- use a supportive tone of voice

- ask permission before delving into the specifics of the veteran’s experience (e.g.,” May I ask you about stressful experiences that people can have during their military service?”)

- thank veterans for disclosing any stressful or traumatic experiences

- if someone is suspected to be at active risk for suicide, they should not be left alone (VA, 2019b)

Once military service is confirmed, the nurse should ask additional questions about the service period to acquire a more detailed assessment of the veteran’s mental health. Military service may have included chemical or biological exposures (e.g., pollutants, solvents, chemical weapons, infectious diseases, biological weapons), psychological trauma (e.g., mental or emotional abuse, moral injury, combat casualties), physical injury (e.g., traumatic brain injury, bullet wound, shell fragment, motor vehicle collision, radiation, noise injury), or unwanted sexual experiences (e.g., military sexual trauma [MST]). According to the VA clinical practice guidelines (CPG), a comprehensive mental health assessment must include screening for PTSD, depression, and suicide risk. Screening for these conditions requires more than asking straightforward questions or completing a checklist. Instead, it encompasses the art of open-ended queries that offer insight into possible symptoms associated with each condition. These assessments can be eye-opening to veterans who may not have formally acknowledged their symptoms as a component of an illness. Table 1 outlines several central aspects of mental health screening assessments (VA, 2019b, 2020d).

Military Cultural Competence

The unique needs and challenges faced by veterans and their families are well-cited across the literature. The need for a culturally competent approach to mental health services and treatment continues to be of the utmost importance. Nurses should convey to veterans that they recognize the importance of the

...purchase below to continue the course

Combat Stress

Stress is a normal component of everyday life; once the stressor is removed, an individual will typically resume their normal behaviors. However, veterans are often impacted by combat stress (also known as battle stress), which is a natural reaction to the mental and emotional strain placed on the mind and body in dangerous and traumatic situations. Combat stress can be challenging to detect since the symptoms can vary and include physical, emotional, and behavioral manifestations. The most common symptoms of combat stress include:

- irritability and angry outbursts, including changes in personality or other behaviors

- excessive worry and anxiety

- withdrawal from others

- headaches and fatigue

- depression and apathy

- loss of appetite

- sleep disturbances (Military OneSource, 2018)

There are several strategies to help veterans cope with combat stress. These include the following:

- return to a regular routine as soon as possible by attending to personal health

- consume a healthy, well-balanced diet with regular meals

- engage in daily exercise

- focus on sleep hygiene and adequate rest, at least 7 hours of sleep per night

- employ relaxation techniques such as deep breathing or meditation

- address spirituality and spiritual needs (e.g., prayer, guidance from a chaplain, religious services)

- engage in leisurely activities

- seek help and counseling (e.g., individual counseling, group therapy, or support from friends and loved ones; Military OneSource, 2020)

Combat Stress and Stress Disorders

Combat stress is often confused with stress disorders, such as acute stress disorder (ASD) and PTSD; however, there are key distinctions between these conditions. Combat stress typically occurs for brief periods and is considered a natural reaction to the traumatic events endured during a deployment. Furthermore, these symptoms usually resolve after a service member returns home. In contrast, ASD and PTSD are similar psychiatric conditions characterized by neural functioning changes in response to overwhelming stress, trauma, or horror. Both ASD and PTSD may be preempted by either direct or indirect exposure to the trauma, including bearing witness to or hearing about horrific events. In both conditions, symptoms are not due to medication, substance use, or any other identifiable illness and cause significant distress or functional impairment. In many cases, PTSD may be a continuation of ASD. Table 3 briefly clarifies the main differences between these conditions according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013).

PTSD

According to the VA (2018), the percentage of veterans affected by PTSD varies by service era as follows:

- Approximately 11 to 20 of every 100 veterans who served in Operations Iraqi Freedom (OIF) or Enduring Freedom (OEF) are diagnosed with PTSD in a given year.

- About 12 of every 100 Gulf War (Desert Storm) veterans have PTSD in a given year.

- An estimated 30 of every 100 Vietnam War veterans develop PTSD in their lifetime (VA, 2018).

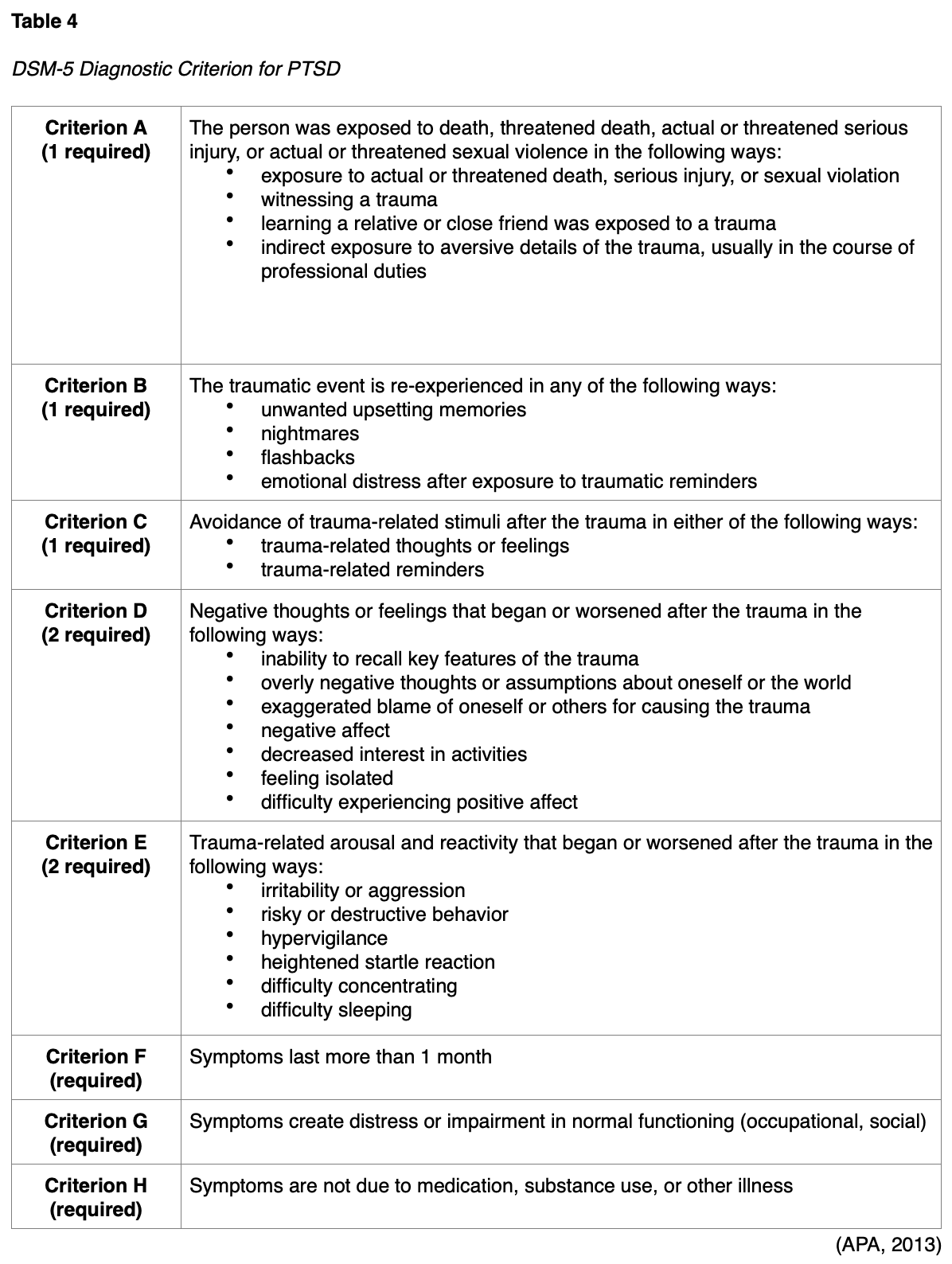

Acute PTSD lasts at least 1 month, but no longer than 3 months, whereas chronic PTSD lasts longer than 3 months. Less commonly, some cases of PTSD may occur years or even decades after the traumatic event(s). According to the DSM-5, the main symptoms of PTSD include concerning intrusions about, and avoidance of, memories associated with the traumatic event. Table 4 outlines the full criteria required for the diagnosis of PTSD (APA, 2013).

Screening for PTSD

Various screening instruments are used to evaluate for PSTD, such as the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), which is a 20-item tool. Other examples of validated PTSD screening instruments include:

- Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5)

- Short Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview (SPRINT)

- Trauma Screening Questionnaire (TSQ; APA, 2013; VA, 2019b)

Regardless of the screening tool used, all positive cases must be followed by a structured clinical interview to confirm the presence of all of the aforementioned criteria, which is the gold standard for diagnosing PTSD (APA, 2013; VA, 2019b).

Treatment for PSTD

The VA last updated their CPGs for PTSD in 2017. They recommend engaging patients in shared decision-making (SDM), including educating patients about effective treatment options and developing a treatment plan based on individual needs and preferences. The VA (2017) recommends individualized, trauma-focused psychotherapy as a highly recommended treatment for PTSD. Trauma-focused psychotherapy focuses directly on the memory of the traumatic event. Veterans undergoing this type of psychotherapy typically attend 8 to 16 sessions exploring the traumatic event. Trauma-focused psychotherapy utilizes various techniques, such as visualizing, analyzing the trauma (i.e., through talk or reflection), and altering unhelpful beliefs about the trauma. Trauma-focused therapies with the most robust evidence include the following (National Center for PTSD, 2019; VA, 2017):

- Prolonged Exposure (PE) includes relaxation skills, recalling details of the traumatic memory, reframing negative thoughts about the trauma, writing a letter about the traumatic event, or holding a farewell ritual to leave the trauma in the past.

- Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) teaches the veteran to reframe negative thoughts about the trauma by talking with the mental health provider about negative thoughts and completing short writing assignments.

- Eye-Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) helps the veteran process and make sense of the trauma and involves calling the trauma to mind while paying attention to a back-and-forth movement or sound.

When individual trauma-focused psychotherapy is not readily available, not preferred, or ineffective, the VA (2017) and the National Center for PTSD (2019) recommend the following medications to treat PTSD. Four antidepressant medications are recommended for monotherapy treatment:

- sertraline (Zoloft)

- paroxetine (Paxil)

- fluoxetine (Prozac)

- venlafaxine (Effexor)

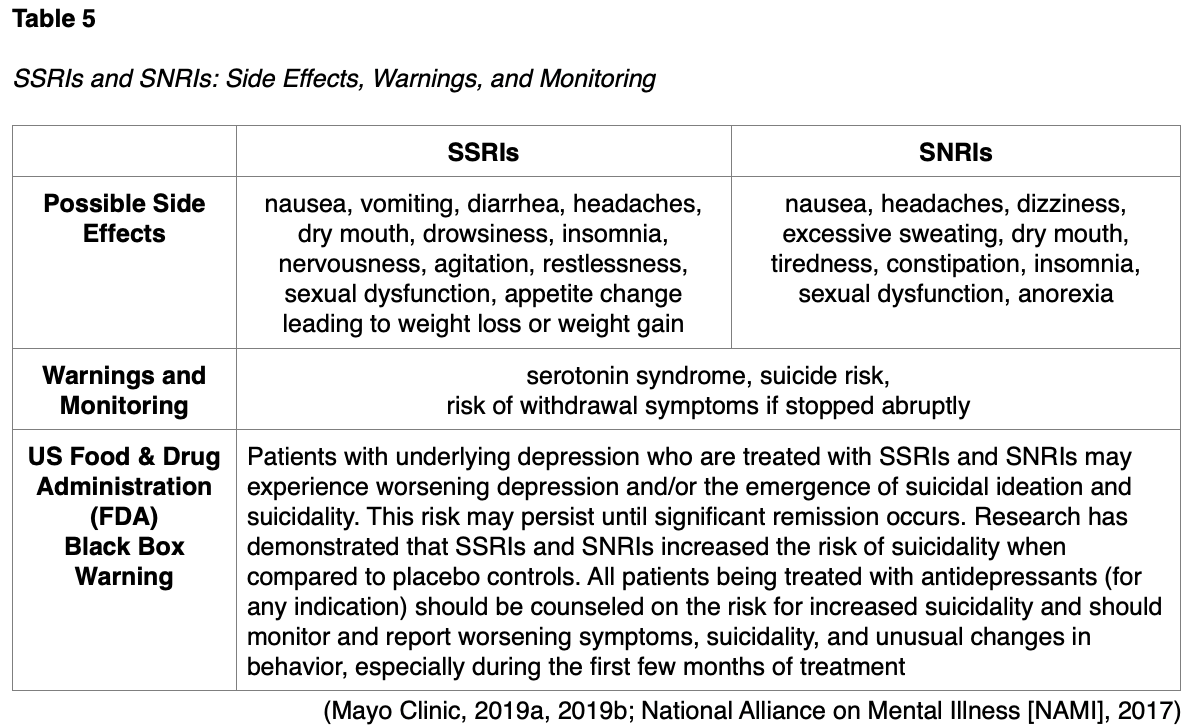

Fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), and sertraline (Zoloft) are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). SSRIs are usually the safest initial choice for PTSD, as they are associated with the fewest side effects. Venlafaxine (Effexor) is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). Both SSRIs and SNRIs can increase serotonin levels in the body, posing a risk for serotonin syndrome, which is characterized by agitation, anxiety, confusion, high fever, sweating, tremors, a lack of coordination, dangerous fluctuations in blood pressure, and a rapid heart rate. Serotonin syndrome is a potentially life-threatening condition for which patients must seek immediate medical attention. Nurses should counsel patients on the importance of not abruptly stopping the medication, as withdrawal symptoms may occur with the sudden discontinuation of SSRIs and SNRIs. Withdrawal symptoms are most commonly seen with abrupt discontinuation of paroxetine (Paxil) and venlafaxine (Effexor). All of these medications should be started at lower initial doses and titrated up as indicated and tolerated. Table 5 outlines the possible side effects of the SSRIs and SNRIs (Mayo Clinic, 2019a, 2019b; VA, 2017).

Caution is advised when prescribing venlafaxine (Effexor) to patients with hypertension. Patients who are prescribed venlafaxine XR (Effexor) should have their blood pressure checked at baseline, periodically after starting, and following any dose increase to evaluate for hypertension. The risk for hypertension with this medication is dose-dependent and heightens with dose levels of 225 mg or higher (VA, 2017; Mayo Clinic, 2019a, 2019b).

TBI and Veterans’ Mental Health

The American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS, 2019) defines TBI as a disruption in brain function and/or structure due to external physical force. A mechanical force or trauma external to the body leads to the brain’s rotational acceleration within the skull. The brain moves rapidly back and forth inside the skull, prompting a cascade of events, such as chemical changes, neuronal depolarization, metabolic derangements at a cellular level, and decreased blood flow. The stretching, damage, and/or death of brain cells associated with the injury subsequently provokes a clinical syndrome characterized by an immediate and/or a transient alteration in brain function. The impact of a TBI on brain function can cause varying symptoms and damage to the brain based on the extent of the injury (AANS, 2019). TBI and PTSD are sometimes called the invisible wounds of war since no obvious physical deformities or injuries are evident. Kulas and Rosenheck (2018) studied more than 160,000 veterans diagnosed with mild TBI, PTSD, or both disorders. They concluded that PTSD serves a dominant role in the development of psychiatric difficulties in veterans. Miles and colleagues (2017) studied 583,733 veterans in the Veterans Health Administration national patient care database, examining the prevalence of TBI and mental health disorders in combat veterans. Their analysis revealed a strong link between TBI and mental health disorders, particularly PTSD, among veterans

Causes of TBI in veterans may include, but are not limited to, the following:

- blow to the head

- nearby blast or explosion

- sudden abrupt stops or changes in movement (Jak et al., 2019; VA, 2021)

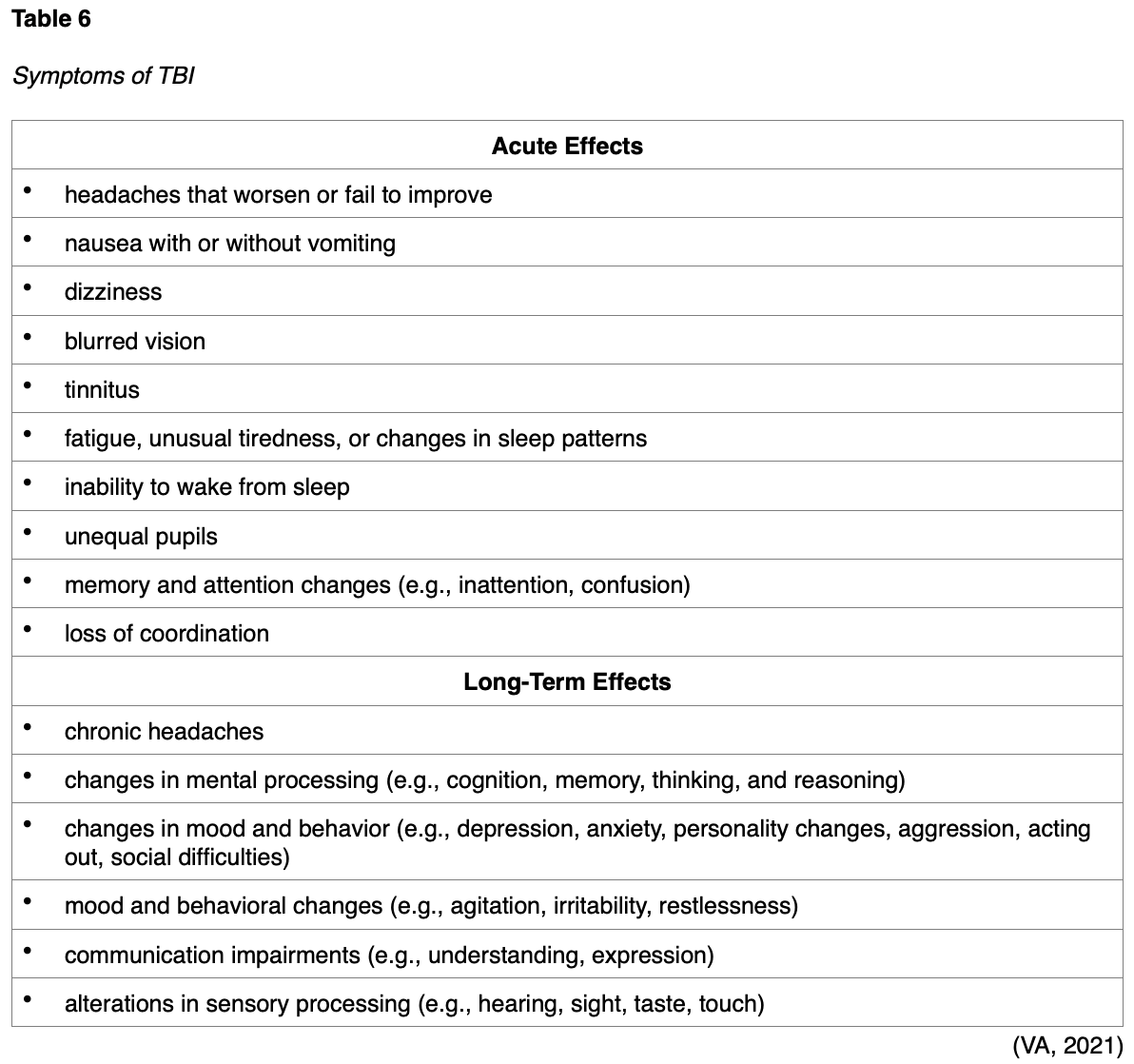

Symptoms of TBI can range from mild to severe, and most are acute, resolving with rest. However, the lingering symptoms following the acute phase of TBI can impact functioning and long-term quality of life and contribute to significant disability. Many veterans suffer from the lingering neurological deficits of TBI, but symptoms are often unpredictable and inconsistent. Table 6 lists some of the acute and long-term symptoms of TBI (Jak et al., 2019; VA, 2021).

Treatment for TBI

PTSD is highly comorbid with mild TBI, a combination observed in military personnel returning from combat. Since depression, PTSD, and suicidal thinking are all associated with TBI and its recovery in veterans, the VA (2021) recommends treatment with combined psychotherapy for PTSD and TBI. A hybrid psychotherapeutic approach combining cognitive training for TBI with cognitive processing therapy (CPT) for PTSD was efficacious in a clinical trial among military veterans affected by both disorders. The clinical trial randomly assigned 100 veterans with PTSD and mild to moderate TBI to receive CPT or the hybrid CPT-compensatory cognitive training. The combined therapy was delivered individually for 12 weekly 60- to 75-minute sessions. At the end of treatment and then 3 months later, both groups showed improvements in lingering TBI symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and quality of life. Combined therapy was also associated with improvements in multiple neuropsychological functioning domains (Jak et al., 2019; Stein, 2020). Rehabilitation is an essential aspect of TBI treatment in veterans. Most treatment plans are comprehensive and multifactorial, addressing the areas of deficit. Some of the most common treatments include one or more of the following:

- physical therapy

- occupational therapy

- speech and language therapy

- recreational therapy

- psychotherapy

- family and group therapies (VA, 2021)

The VA’s Polytrauma/TBI System of Care is an integrated network of specialized rehabilitation programs dedicated to serving veterans with TBI and/or more severe secondary injuries. The Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) is a program that serves veterans and their families who have experienced a TBI by providing medical care, innovative research initiatives, and educational programs (VA, 2021).

Depression

According to the NIMH (2018), major depressive disorder—frequently referred to as depression—is a serious mental health condition that can cause severe impairment in thinking and daily functioning. Depression is among the most common mental disorders in the US. To be diagnosed with the condition, symptoms must be present for at least 2 weeks. Without treatment, depression can have devastating complications. Research suggests that depression is caused by a combination of factors, including genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological. Depression can occur at any age but is most prevalent in adulthood. Some of the most common risk factors include personal or family history of depression, significant life changes, stress, trauma, and certain medications (NIMH, 2018). In veterans, depression is most commonly triggered by life crises, especially trauma, combat injury, natural disasters, or MST. However, life changes—including the loss of a loved one or fellow soldier, retirement, deployment, financial problems, job change, or divorce—are also linked to veterans’ stress and depression. Exposure to trauma can alter the body’s response to fear and stress, leading to depression. While not every veteran exposed to trauma or life changes will subsequently develop depression, this condition is nearly 3 to 5 times more likely in those with PTSD than those without PTSD (National Center for PTSD, 2019; VA, 2016).

Symptoms of a depressive disorder include:

- loss of interest or pleasure in hobbies and activities

- a persistently sad, anxious, or “empty” mood

- feeling hopeless or having a pessimistic attitude

- changes in appetite or weight

- sleep disturbances

- irritability, agitation, or restlessness

- fatigue

- moving or talking slowly

- feelings of low self-worth, guilt, or shortcomings

- difficulty concentrating

- suicidal thoughts or intentions (APA, 2013; NIMH, 2018; VA, 2016)

Screening for Depression

The VA (2016) recommends initially screening veterans for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2). The PHQ-2 asks the following priority questions (APA, 2013; VA, 2016):

- Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems?

- little interest or pleasure in doing things

- feeling down, depressed, or hopeless

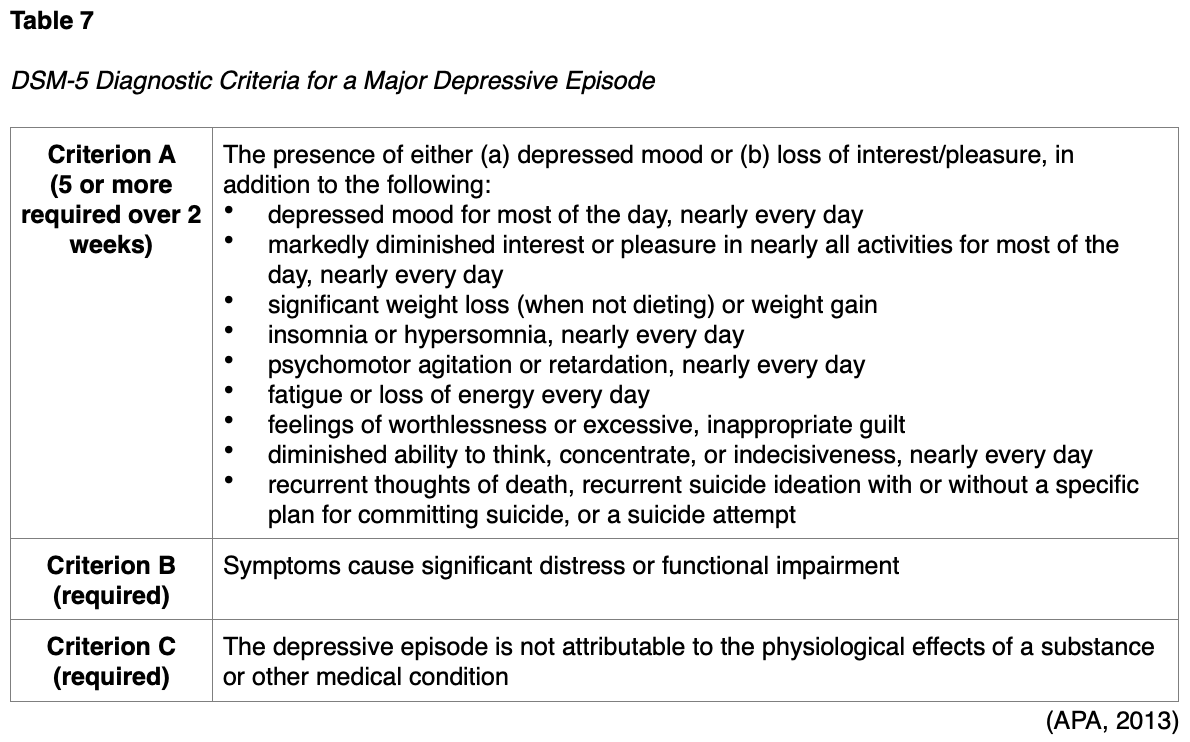

Patients with suspected depression should undergo additional screening with the PHQ-9 tool, which is a multipurpose, 9-item symptom checklist used to screen for, diagnose, monitor, and measure the severity of depression. It incorporates DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for depression and a question that screens for the presence and duration of suicidal ideation. The tool is brief and easily used in clinical practice. It is completed by the patient, rapidly scored by the nurse or clinician, and can be used repeatedly to assess for improving or worsening symptoms. In addition to the PHQ-9, nurses must evaluate the acute safety risks (e.g., harm to self or others, psychotic features) and administer an appropriate assessment of the patient’s functional status, medical history, past treatment, and family history. Table 7 reviews the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for depression (VA, 2016).

Treatment for Depression

An individualized treatment plan should be developed using shared decision-making and will vary based on the patient’s severity level (mild, moderate, or severe) as outlined below in Table 8. Treatment for depression may include counseling, therapy, and/or antidepressant medication. The most effective treatment for depression is a combination of psychotherapy with antidepressant medication (VA, 2016).

Evidence-Based Psychotherapy for Depression

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). ACT is an action-oriented intervention in which veterans learn to stop avoiding, denying, and struggling with their inner emotions. Instead, they learn to accept these deeper feelings as appropriate responses to specific situations. ACT emphasizes acceptance of emotional distress and engagement in goal-directed behaviors to reduce symptom severity. To facilitate effective behavior change, ACT emphasizes the identification of personal values and learning to help veterans commit to making necessary changes in their behavior (Stein, 2020; VA, 2016).

Behavioral Therapy/Behavioral Activation (BT/BA). BT refers to a class of psychotherapy interventions that treat depression by teaching veterans to increase rewarding activities. Patients learn to track their activities and identify the affective and behavioral consequences. Patients then learn techniques to schedule activities to improve their mood. BT emphasizes training patients to monitor their symptoms and behaviors to identify the relationships between them. BA is a specific technique of BT that targets the link between avoidant behavior and depression to expand the treatment component of BT. BA is essentially a coping strategy that strives to increase behaviors that bring the patient into contact with positive reinforcements and decrease behaviors that impede contact with positive reinforcement (Stein, 2020; VA, 2016).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Strong clinical evidence supports the use of CBT as an effective treatment for depression. CBT helps patients assess and restructure negative thinking patterns associated with depression. CBT’s goal is for the veteran to recognize negative thoughts and learn positive and effective coping strategies. CBT is time-limited and typically consists of 8–16 sessions. Veterans learn to track their thoughts and activities to identify the affective and behavioral consequences. They subsequently learn techniques to change their way of thinking and activities to improve mood. CBT has demonstrated efficacy in veterans, active service members, and family members suffering from depression. CBT can also be administered via computer-based programs, which are referred to as computer-based CBT (CCBT; Stein, 2020; VA 2016).

Interpersonal Therapy (IPT). IPT focuses on improving problems within personal relationships as a core component of depression. While an event or a relationship may not always cause depression, depression affects relationships and can create interpersonal problems. IPT is a short-term treatment that teaches veterans to evaluate their interactions to understand and improve how they relate to others. IPT is derived from attachment theory and treats depression by focusing on improving interpersonal functioning and exploring relationship-based difficulties. IPT specifically targets four primary areas: interpersonal loss, role conflict, role change, and interpersonal skills (Stein, 2020; VA, 2016).

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT). MBCT integrates traditional CBT interventions with mindfulness-based skills to help patients attend to the present moment in a non-judgmental, accepting manner. Unlike CBT, MBCT does not modify or eliminate dysfunctional thoughts and instead focuses on assisting veterans to become more detached and observe their thoughts objectively, without necessarily attempting to change them. MBCT employs meditation, imagery, experiential exercises, and relaxation techniques (Stein, 2020; VA, 2016).

Problem-Solving Therapy (PST). PST is a structured psychological intervention that helps veterans focus on developing specific coping skills for problem areas. Through a collaborative relationship with the therapist, veterans learn how to identify and prioritize key problem areas and break them into manageable tasks to develop appropriate coping behaviors and solutions (Stein, 2020; VA, 2016).

Pharmacotherapy

Antidepressant medications are the pharmacological treatment of choice for depression to reduce or control symptoms. Nurses should counsel veterans that antidepressants typically take 2-4 weeks to yield an effect and 12 weeks to achieve the maximum benefit. For veterans who demonstrate only a partial or no response to initial monotherapy after a minimum of 4-6 weeks of treatment, the VA recommends switching to another monotherapy (medication or psychotherapy) or augmenting therapy by adding a second agent. After the initiation of therapy or a change in treatment, veterans should be monitored at least monthly until remission is achieved. For those who achieve remission on antidepressants, the medication should be continued at the therapeutic dose for at least 6 months to reduce the risk of relapse. The VA (2016) recommends the following medications with strong evidence:

- SSRIs (e.g., citalopram [Celexa], escitalopram [Lexapro], fluoxetine, [Prozac], paroxetine [Paxil], and sertraline [Zoloft]; see Table 5 for side effects and monitoring)

- SNRIs (e.g., duloxetine [Cymbalta], venlafaxine [Effexor], levomilnacipran [Fetzima], and desvenlafaxine [Pristiq]; see Table 5 for side effects and monitoring)

- Mirtazapine (Remeron)

- common side effects include sedation, increased appetite, weight gain, dizziness, and elevated cholesterol levels

- rare and serious side effects include angle-closure glaucoma (eye pain, changes in vision, swelling or redness in or around the eye), agranulocytosis (low white blood cells), serotonin syndrome, and a black box warning for increased suicidality

- Bupropion (Wellbutrin)

- common side effects include headaches, weight loss, dry mouth, trouble sleeping (insomnia), nausea, dizziness, constipation, fast heartbeat, and sore throat

- side effects typically improve over the first 2 weeks of treatment

- affects mostly the brain chemical dopamine and does not carry a risk for serotonin syndrome

- rare side effects include a skin rash, sweating, ringing in the ears, shakiness, stomach pain, muscle pain, thought disturbances, anxiety or angle-closure glaucoma, and a black box warning for increased suicidality (NAMI, 2017, 2020)

The VA (2016) recommends tailoring the patient’s treatment for uncomplicated mild to moderate depression based on the following factors:

- patient preference

- safety and side effect profile

- history of prior response to a specific medication

- presence of concurrent medical illnesses

- concurrently prescribed medications

- cost of drugs

- provider competence

The current evidence does not support recommending one specific evidence-based psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy over another (VA, 2016).

Grief and Bereavement

According to Mental Health America (n.d.), grief consists of the physical, psychological, cognitive, spiritual, and behavioral responses to loss or the perceived threat of loss. Bereavement is the state of having suffered a loss. While these terms are often used interchangeably, bereavement is often the trigger that starts the grieving process. In veterans, many other situations and circumstances incite the grieving process. For veterans, grief may develop from the loss of:

- a military comrade who died in battle

- a sense of closeness with fellow service members

- identity as a member of the armed forces

- physical health and ability (e.g., disability acquired during service, such as amputation of a limb)

- mental health such as PTSD, loss of sense of safety and control, or lingering effects of a TBI (VA, 2015, 2020b)

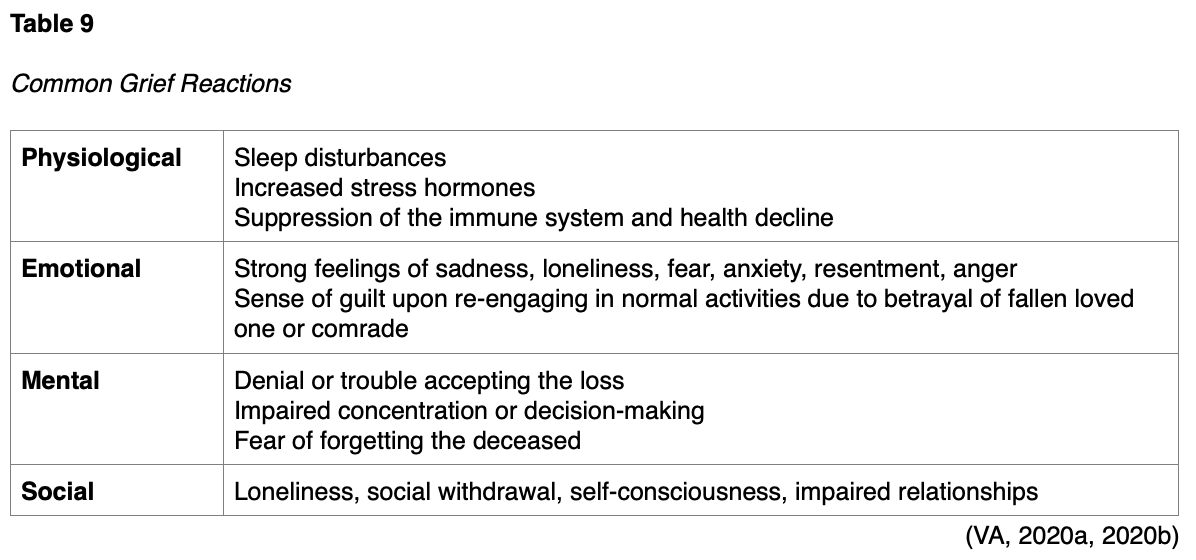

Veterans may also experience survivor guilt, which is a sense of remorse for having survived when others did not. Loss is an incredibly stressful and painful event, and the expression of grief is personal. Grief is a process, and it is common for feelings to waver through periods of exacerbation and relief with varying timelines in the aftershock of loss. Grief reactions can impair physical, behavioral, emotional, and spiritual well-being and are impacted by cultural backgrounds and beliefs. While there is no specific or “normal” way to grieve, there are several common grief reactions that often induce physiological, emotional, mental, and social symptomatology, as listed in Table 9. Thoughts and images of the deceased are common in grief reactions, which may be accompanied by auditory, visual, or tactile illusions (VA, 2015, 2020a, 2020b).

Complicated grief causes prolonged sadness, guilt, or anger. These emotions often lead to behavior changes, such as:

- withdrawal from all interactions with friends and family members (social isolation)

- lashing out at others

- obsessively ruminating on past events (VA, 2020a)

Distinguishing Grief from Depression

According to the DSM-5, feelings of emptiness and loss are predominant in grief, and symptoms often decrease in intensity over days to weeks. In contrast, depression is characterized by a persistently depressed mood and the inability to anticipate happiness or pleasure. Self-esteem is typically preserved in grief, whereas in depression, feelings of worthlessness and self-loathing are common. If a bereaved individual thinks about death and dying, their thoughts are usually focused on the deceased and possibly “‘joining” the deceased. In depression, these thoughts are focused on ending one’s own life due to intolerable feelings of worthless, not deserving to live, or being unable to cope with the pain of depression (APA, 2013).

Managing Grief

The VA (2015, 2020b) recommends the following self-care strategies to grieving veterans:

- allow time to grieve

- talk to others about the grieving experience and seek support from family, friends, and comrades

- stay active and busy

- exercise regularly

- engage in purposeful work that is consistent with personal values

- consume a healthy diet

- postpone making any major life decisions (e.g., moving or changing jobs)

- consider journaling to record thoughts and feelings

- focus on spiritual or religious beliefs or seek guidance from a chaplain or pastor

- consider seeking professional help from a counselor or therapist (VA, 2015, 2020b)

Suicide and Suicide Prevention

Suicide is a complex, multifactorial phenomenon involving various risk factors and warning signs. Suicide is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2019a) as “death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with an intent to die as a result of the behavior.” Suicidal behavior encompasses suicide attempts (a non-fatal, self-directed, potentially injurious act intended to result in death that may or may not result in injury) and suicide ideation (thinking about, considering, or planning suicide). Suicide has devastating psychological impacts on family, friends, and loved ones, and it can provoke a consequential ripple effect on others and the community. According to statistics from the National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (VA, 2019a), the number of veteran suicides exceeded 6,000 each year between 2008 and 2017. In 2017, the veteran suicide rate was 1.5 times the rate for non-veteran adults, with an average of 16.8 veteran suicide deaths per day and a total of 6,139 deaths throughout the year. Firearms were the method of suicide in 70.7% of male veteran suicide deaths and 43.2% of female veteran suicide deaths in 2017 (VA, 2019a).

Suicide Myths and Realities (VA, 2020c)

Myth: Asking about suicide will plant the idea in a person’s head.

Reality: Asking about suicide does not create suicidal thoughts. Asking the question simply gives the patient permission to talk about their thoughts or feelings.

Myth: There are talkers, and there are doers.

Reality: Most people who die by suicide have previously communicated some intent. Someone who talks about suicide allows the clinician to intervene before suicidal behaviors occur.

Myth: If somebody wants to die by suicide, there is nothing anyone can do about it.

Reality: Most suicidal ideations are associated with treatable disorders. Helping someone find a safe environment for treatment can save a life. The acute risk for suicide is often time-limited. If someone helps the person survive the immediate crisis and overcome the strong intent to die by suicide, a positive outcome is much more likely.

Myth: They really wouldn’t commit suicide because they…

just made plans for a vacation

have young children at home

made a verbal or written promise

know how dearly their family loves them

Reality: The intent to die can override rational thinking. Someone experiencing suicidal ideation or intent must be taken seriously and referred to a clinical provider who can further evaluate their condition and provide treatment as appropriate.

Warning Signs and Screening

Although statistical data demonstrates that most people who die by suicide received some form of health care services within the year preceding their death, suicidal ideation is rarely detected. Nurses must develop a keen awareness and understanding of the risk and protective factors associated with suicide to identify individuals at risk for suicide across clinical settings. Nurses must also acquire the skills necessary to evaluate if a veteran is in distress, depressed, crisis, or heightened risk prompting timely intervention. While suicide does not have a single cause, the risk for suicide generally increases as the current number of contributing risk factors rises. The more warning signs present, the greater the risk of suicide becomes, intensifying the need for timely assessment and intervention (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention [AFSP], 2019; CDC, 2019b).

A prior suicide attempt is the most predictive risk factor for suicide. The following additional warning signs are correlated with the highest likelihood of the short-term onset of suicidal behaviors:

- threatening, talking, or thinking about hurting or killing one’s self

- searching for ways to kill oneself, including seeking access to drugs or other lethal means (e.g., stockpiling or obtaining weapons, strong prescription medications, or items associated with self-harm)

- talking, writing, or posting on social media about death, dying, and suicide

- self-destructive behavior such as drug abuse (AFSP, 2019; CDC, 2019b; Veterans Crisis Line, n.d.)

Veterans who are considering suicide may exhibit signs of depression, anxiety, or low self-esteem. The Veterans Crisis Line (n.d.) and the VA (2019c) CPG for suicide have identified the following warning signs that may indicate a veteran is at increased risk of suicide:

- performing poorly at work or school

- acting recklessly or engaging in risky activities that could lead to death (e.g., driving at fast speeds or running red lights)

- showing unusual rage, anger, frustration, or violent behavior (e.g., punching holes in walls or getting into fights)

- giving away prized possessions, putting affairs in order, or tying up loose ends

- anxiety, agitation, sleeplessness, or mood swings

- hopelessness, expressing/feeling that there is no way out or reason to live

- increasing alcohol or drug abuse

- withdrawing from family and friends (Veterans Crisis Line, n.d.; VA, 2019c)

These higher-level warning signs are medical emergencies, as they warrant immediate attention, evaluation, referral, and hospitalization. Any individual who is displaying these warning signs is considered to be at high-risk for suicide and requires immediate intervention to ensure safety. These individuals should be immediately referred for admission to an inpatient facility, as specialty care is urgently needed. If a placement is not possible, refer patients to their local emergency department. Suicide precautions and one-on-one monitoring should be employed until the imminent risk declines (Suicide Awareness Voices of Education, 2019; VA, 2019c).

Suicide Risk Assessment

A suicide risk assessment is a process in which clinical information is gathered to determine an individual’s risk for suicide. The risk for suicide is multifactorial, premised on the individual’s suicidal behaviors, warning signs, risk factors, and protective factors. A risk assessment identifies behavioral and psychological characteristics associated with an increased risk for suicide, allowing health care professionals to implement effective, evidence-based treatments and interventions to reduce this risk. The risk assessment for suicide is an ongoing process, as suicidal behaviors can fluctuate quickly and unpredictably. A complete risk assessment must include the following vital aspects:

- information about past, recent, and present suicidal ideation and behavior

- details on the patient’s context and history

- synthesis of this information into a prevention-oriented suicide risk formulation anchored in the patient’s life context (AFSP, 2019)

According to the VA (2019b) CPG on suicide, an assessment of risk factors as part of a comprehensive evaluation of suicide risk should include the following components:

- current suicidal ideation

- prior suicide attempt(s)

- current psychiatric conditions (e.g., mood disorders, substance use disorders) or symptoms of any preexisting psychiatric condition (e.g., hopelessness, insomnia, and agitation)

- prior psychiatric hospitalization

- recent biopsychosocial stressors

- availability of firearms

The VA (2019b) has identified the following factors associated with a veteran’s military service, which may contribute to their risk of a suicide attempt. These veteran-specific risks include:

- frequent deployments

- deployments to hostile environments

- exposure to extreme stress

- physical/sexual assault while serving

- length of deployments

- service-related injury

A complete suicide risk assessment must also include a validated, evidence-based screening tool, which encompasses a set of directed questions to assess the risk level. A critical aspect of suicide prevention involves tailoring interventions to the perceived suicide risk level. Nurses and clinicians must understand how to perform a proper risk assessment, ascertain the patient’s risk level, and respond according to the evidence-based guidelines. Several tools are available for use across various clinical settings, and the most common are outlined below (National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention [Action Alliance], 2018).

Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

C-SSRS is one of the most widely used, validated, and evidence-based instruments in suicide risk assessment. The C-SSRS is supported by extensive evidence and existing literature that reinforces the tool’s validity as a screening method for longitudinally predicting future suicidal behaviors. This tool provides a framework to assess suicide risk, determine the risk level, and guide appropriate action according to that risk level. Also, the C-SSRS measures non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), which is a deliberate self-harm behavior performed without the intent to die (Brodsky et al., 2018).

Suicide Assessment 5-Step Evaluation and Triage (SAFE-T)

SAFE-T is a tool that incorporates the DSM-5 guidelines for suicide assessment and is used most commonly in emergency departments by clinicians and nurses. The SAFE-T helps identify risk and protective factors; inquire about suicidal thoughts, behavior, and intent; and determine the patient’s risk level. It provides appropriate interventions directly at the bottom of the tool to enhance safety. According to the SAFE-T screening tool, assessing the risk of suicide involves three levels: low, moderate, and high. Table 10 provides an overview of suicide risk stratification, defining features, and accompanying evidence-based interventions (Columbia Lighthouse Project, 2016).

Protective Factors

Protective factors are associated with a lower risk of suicide and have been shown to safeguard individuals from suicidal thoughts and behaviors. According to the CDC (2019b), some of the most well-established suicide protective factors include the following:

- presence of adequate social support and family connections (connectedness)

- effective clinical care for mental, physical, and substance abuse disorders, along with access to a variety of clinical interventions and support for help-seeking

- supportive and effective clinical care from medical and mental health professionals

- skills in coping, problem-solving, conflict resolution, and other nonviolent ways of handling disputes

- cultural and religious beliefs that discourage suicide and support instincts for self-preservation (e.g., intentional participation in religious activities)

Suicide Prevention

For suicide-related issues, prevention offers the most positive impact on veterans and their family members. The VA has focused on the early identification of those experiencing difficulties as the key to suicide prevention. All veterans, at any risk level, should be provided with information on the Veterans Crisis Line, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, as well as local crisis and peer support contacts. The VA (2019c) recommends using CBT interventions focused on suicide prevention for veterans with a recent history of self-directed violence to reduce incidents of future self-directed violence. Evidence-based clinical approaches that help reduce suicidal thoughts and behaviors include the following:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CBTSP)

- The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicide (CAMS)

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

- Connectedness with caring contacts (social/familial support systems) for post-discharge suicide prevention (NIMH, 2019; VA, 2019c)

For patients in a suicidal crisis, nurses should take immediate action and implement a safety plan through the following steps:

- keep patients in a safe health care environment under one-on-one observation

- do not leave suicidal patients alone

- arrange immediate access to care through an emergency department, inpatient psychiatric unit, respite center, or crisis clinic

- screen suicidal patients and their visitors for items that could be used to attempt suicide or harm others

- ensure suicidal patients are kept away from anchor points for hanging and material that can be used for self-injury

- examples of lethal means that are readily available in hospitals and clinics that have been used in suicides include bell cords, bandages, sheets, restraint belts, plastic bags, elastic tubing, and oxygen tubing (Action Alliance, 2018; NIMH, 2019)

Safety Planning

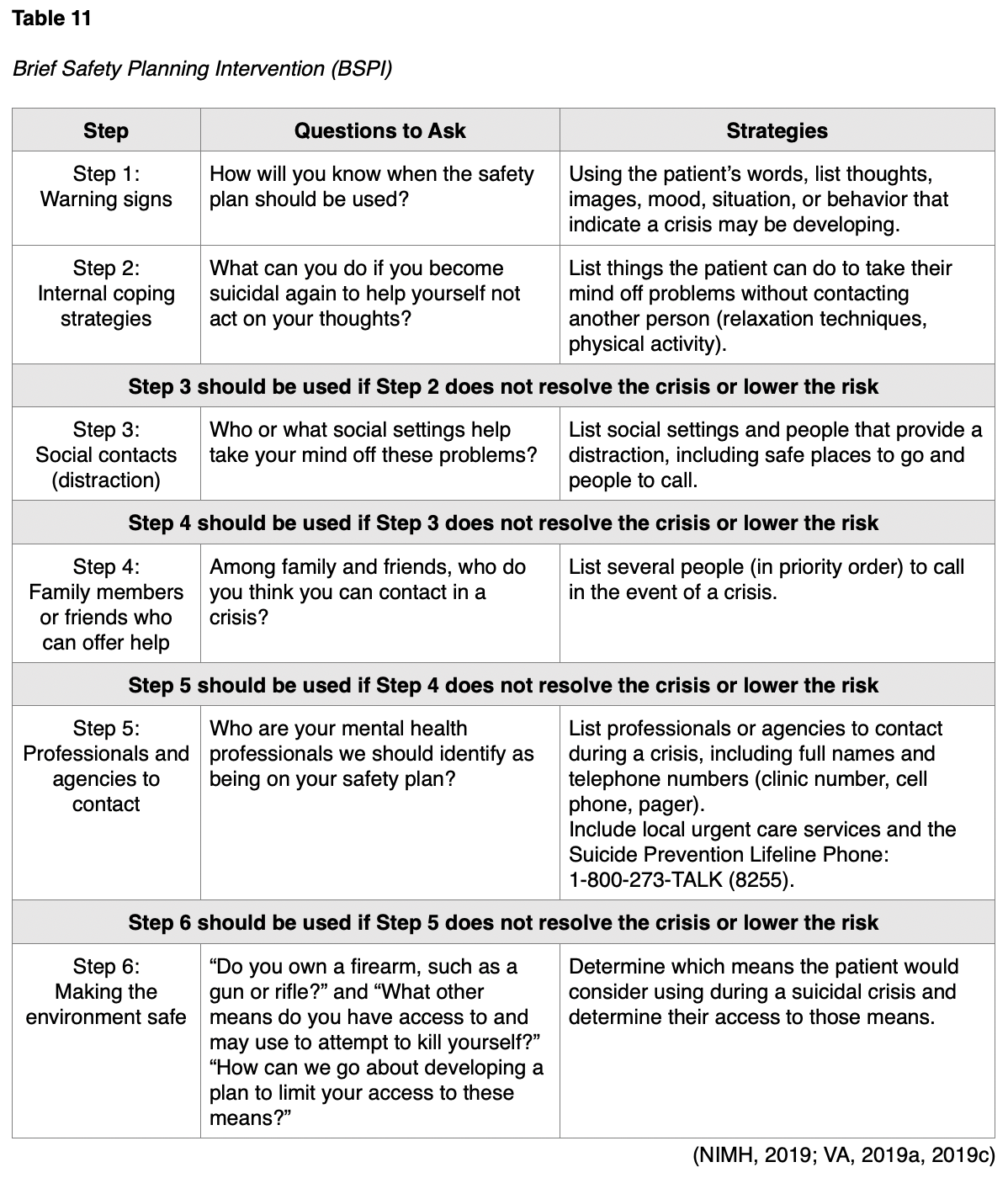

Safety planning is critical and should be conducted by collaboratively identifying possible coping strategies and providing resources to reduce risk. A safety plan is not a “no-suicide contract,” which is not recommended by experts in suicide prevention. Safety planning is an intervention for lowering an individual’s imminent suicide risk following a risk assessment. A trained APRN, nurse, other health care professional should perform safety planning in collaboration with the patient. Components of a safety plan include the following:

- identifying warning signs

- utilization of coping strategies

- ability to socialize with others as a means of distracting from suicidal thoughts

- connection to and contact with family or friends to seek help during a suicidal crisis

- contact information for mental health professionals or resources for assistance

- restricting access to means for completing suicide (NIMH, 2019; VA, 2019a)

Table 11 outlines the 6-step process of safety planning using a brief intervention tool.

Nurses should review and reiterate the patient’s safety plan at every interaction until the patient is no longer at risk for suicide. A safety plan should always include a discussion on how to restrict access to lethal means. When assessing patient’s access to firearms or other lethal means, professionals should inquire about prescription medications and chemicals. Next, they should discuss ways of removing or locking up firearms, other weapons, and medicines during crisis periods (NIMH, 2019; VA, 2019a, 2019c).

Resources for Veterans and Families

When caring for veterans, nurses must be equipped to offer realistic, practical, and useful information regarding mental health care. Veterans and their family members may not be fully aware of the resources and treatment options available. In addition to those listed below, nurses should maintain familiarity with local resources and treatment facilities for referring patients as needed.

Veteran Health Benefits and Services

www.myhealth.va.gov

This website can be accessed by veterans, family members, and caregivers and provides information on veteran health benefits and services.

Veterans Crisis Line

https://www.veteranscrisisline.net/

The Veterans Crisis Line is a VA resource that connects veterans and service members in crisis and their families and friends with information and qualified, caring VA responders through a confidential, toll-free hotline, online chat, and text messaging service. Veterans and their families can call 1-800-273-8255 (Press 1), chat online at www.VeteransCrisisLine.net, or send a text message to 838255 to receive support from specially trained professionals 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year.

VA Mental Health Services

https://www.va.gov/health-care/health-needs-conditions/mental-health/

According to the VA, veterans are entitled to free mental health care for at least a year after separation, regardless of their discharge status, service history, or eligibility for VA health care.

This resource offers training via online self-help portals geared toward overcoming everyday challenges (e.g., anger management, parenting, and problem-solving skills), smartphone apps, telehealth services, or assistance with referrals to nearby VA health facilities.

Military OneSource

https://www.militaryonesource.mil/health-wellness/mental-health/mental-health-resources/

Military OneSource provides a list of confidential resources and support for veterans and their family members based on areas of need, including sexual assault, PTSD, TBI, domestic abuse, child abuse, and beyond.

References

American Association of Neurological Surgeons. (2019). Concussion. https://www.aans.org/en/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Concussion

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. (2019). Risk factors and warning signs. https://afsp.org/risk-factors-and-warning-signs

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

Brodsky, B. S., Spruch-Feiner, A., & Stanley, B. (2018). The zero suicide model: Applying evidence-based suicide prevention practices to clinical care. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9(33). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00033

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019a). Preventing suicide. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/fastfact.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019b). Risk and protective factors. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide/riskprotectivefactors.html

Columbia Lighthouse Project. (2016). SAFE-T with C-SSRS. http://cssrs.columbia.edu/documents/safe-t-c-ssrs/

Jak, A. J. Jurick, S., Crocker, L. D., Sanderson-Cimino, M., Aupperle, R., Rodgers, C. S., Thomas, K. R., Boyd, B., Norman, S. B., Lang, A. J., Keller, A. V., Schiehser, D. M., & Twamley, E. W. (2019). SMART-CPT for veterans with comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder and history of traumatic brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 90(3), 333. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-319315

Kulas, J., & Rosenheck, R. (2018). A comparison of veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder, with mild traumatic brain injury and with both disorders: understanding multimorbidity. Military Medicine, 183(3-4), e114-e122. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usx050

Mayo Clinic. (2019a). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/in-depth/ssris/art-20044825

Mayo Clinic. (2019b). Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/in-depth/antidepressants/art-20044970

Mental Health America. (n.d.). Bereavement and grief. Retrieved January 13, 2021, from https://www.mhanational.org/bereavement-and-grief

Miles, S. R., Harik, J. M., Hunt, N. E., Mignogna, J., Pastorek, N, Thompson, K. E., Freshour, J. S., Yu, H. J., & Cully, J. S. (2017). Delivery of mental health to combat veterans with psychiatric diagnoses and TBI histories. PLOS ONE, 12(9), e0814265. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184265

Military OneSource. (2018). How to deal with combat stress. https://www.militaryonesource.mil/health-wellness/healthy-living/managing-stress/how-to-deal-with-combat-stress/

Military OneSource. (2020). Understanding and dealing with combat stress and PTSD. https://www.militaryonesource.mil/health-wellness/wounded-warriors/ptsd-and-traumatic-brain-injury/understanding-and-dealing-with-combat-stress-and-ptsd/

National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. (2018). Recommended standard care for people with suicide risk. https://theactionalliance.org/resource/recommended-standard-care

National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2017). Types of medication. https://nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Treatments/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication

National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2020). Bupropion (Wellbutrin). https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Treatments/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Bupropion-(Wellbutrin)

National Center for PTSD. (2019). Depression, trauma, and PTSD. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/related/depression_trauma.asp

National Institute of Mental Health. (2018). Depression. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression/index.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health. (2019). Suicide prevention. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/suicide-prevention/index.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health. (2021). Mental illness. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml#part_154784

Statista. (2018). 2.77 million service members have deployed since 9/11. https://www.statista.com/chart/13292/277-million-service-members-have-deployed-since-9-11/

Statista. (2020). Number of veterans in the United States in 2019, by gender. https://www.statista.com/statistics/250271/us-veterans-by-gender/

Stein, M. B. (2020). Psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/psychotherapy-and-psychosocial-interventions-for-posttraumatic-stress-disorder-in-adults#H1772362614

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020a). 2019 national survey on drug use and health: Veteran adults. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2019-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020b). Cultural competence for serving the military and veterans. https://www.samhsa.gov/section-223/cultural-competency/military-veterans

Suicide Awareness Voices of Education. (2019). Warning signs of suicide. https://save.org/about-suicide/warning-signs-risk-factors-protective-factors/

Uniformed Services University. (2018). Military culture course modules. https://deploymentpsych.org/military-culture-course-modules

US Census Bureau. (2020). Census Bureau releases new report on veterans. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/veterans-report.html

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2015). Dealing with sadness or grief after a loss. https://www.va.gov/vetsinworkplace/docs/em_eap_dealing_loss.asp

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2016). Management of major depressive disorder. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/mdd/

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2017). Management of post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction 2017. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2018). How common is PTSD in veterans? https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_veterans.asp

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2019a). 2019 national veteran suicide prevention annual report. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf

US Department of Veteran’s Affairs. (2019b). Military health history: Pocket card for health professions trainees & clinicians. https://www.va.gov/OAA/archive/Military-Health-History-Card-for-print.pdf

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2019c). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/srb/VADoDSuicideRiskCPGProviderSummaryFinal5088212019.pdf

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2020a). Grief: Different reactions and timelines in the aftermath of loss. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/related/related_grief_reactions.asp

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2020b). Grief: Taking care of yourself after a loss. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/related/related_problems_grief.asp

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2020c). Suicide prevention: How to recognize when to ask for help. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/whentoaskforhelp.asp

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2020d). VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/index.asp

US Department of Veterans Affairs. (2021). VA research on traumatic brain injury (TBI). https://www.research.va.gov/topics/tbi.cfm

Veterans Crisis Line. (n.d.). Signs of crisis. Retrieved January 15, 2021, from https://www.veteranscrisisline.net/education/signs-of-crisis