About this course:

With the rise of the opioid epidemic that continues to plague the US, APRNs must ascertain an accurate and comprehensive understanding regarding best practices for opioid prescribing for pain management to preserve the integrity of clinical practice, safeguard patient care, and reduce the risk for opioid use disorders. The purpose of this module is to provide a comprehensive overview of best-practice opioid prescribing guidelines, including proper monitoring of patients on long-term opioid therapy, as well as the clinical features of opioid use disorders.

Course preview

3-Part Module Series on Pain Management

For RNs/LPNs:

- Pain Management Nursing CE Course Part 1: The Pathophysiology and Classification of Pain (All Users)

- Pain Management NursingCE Course Part 2: The Non-Opioid Management of Pain for RN/LPNs

- Pain Management NursingCE Course Part 3: Opioid Administration and Monitoring for RN/LPNs

For APRNs:

- Pain Management Nursing CE Course Part 1: The Pathophysiology and Classification of Pain (All Users)

- Pain Management Nursing CE Course for APRNs Part 2: The Non-Opioid Management of Pain

- Pain Management Nursing CE Course for APRNs Part 3: Opioid Prescribing

Pain Management Nursing CE Course for APRNs Part 3: Opioid Prescribing

Objectives

By the completion of this module, the learner should be able to:

- Define opioids and distinguish between opioid agonists, partial agonists, mixed agonist-antagonists, and opioid antagonists, identifying specific medications within each category.

- Demonstrate competency in best-practice opioid prescribing guidelines, including the proper prescribing and monitoring of patients on long-term opioid therapy.

- Identify the potential for opioid misuse and abuse, the defining features of opioid use disorder (OUD), as well as strategies to identify and mitigate opioid misuse and OUD.

This 3-part series on pain management strives to provide a thorough review of the principles of pain management, the critical assessment, non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions, as well as strategies to safeguard patient care, improve patient outcomes, and uphold the practice of the APRN.

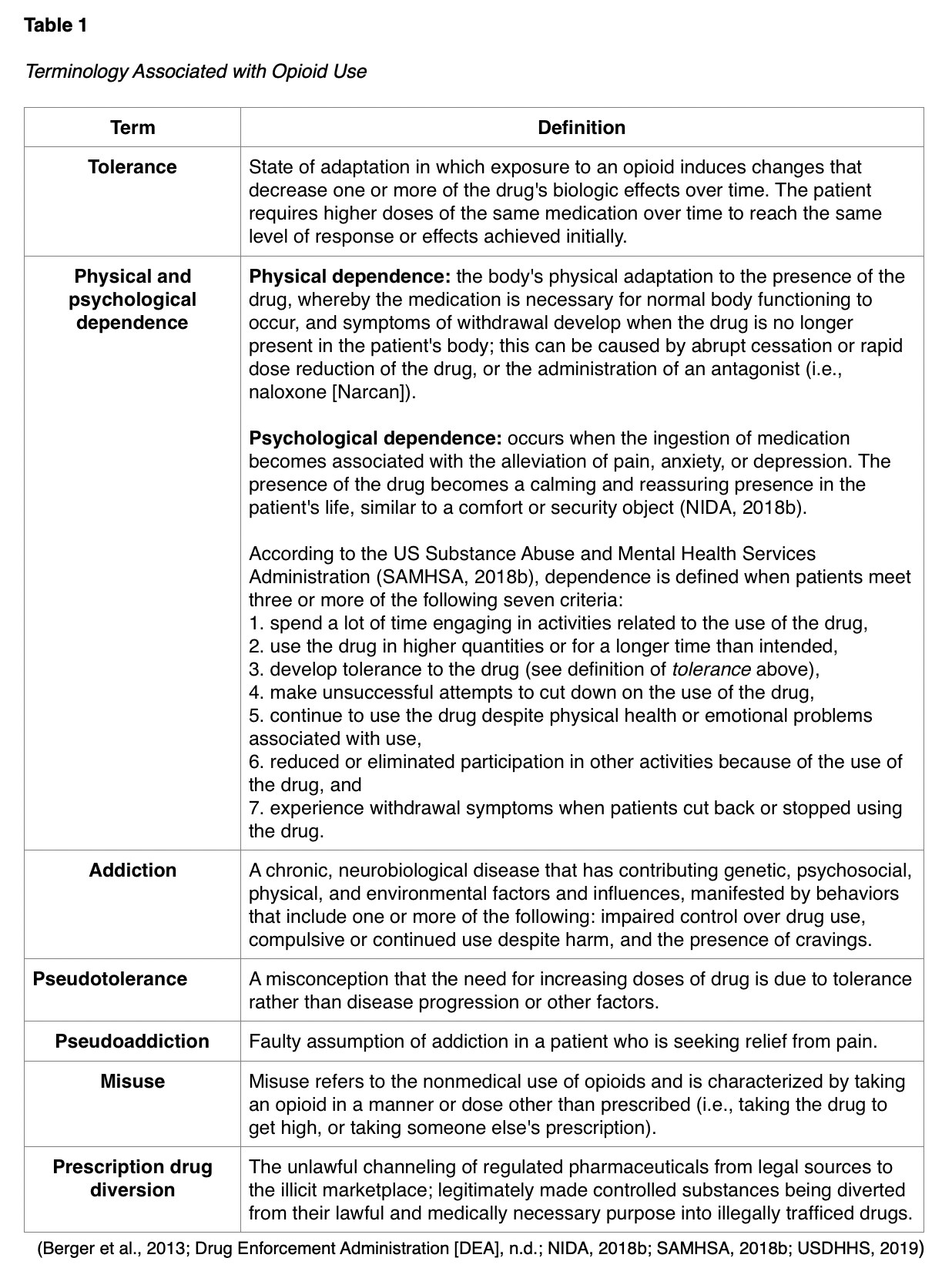

It is vital that the APRN properly understands terms related to opioid use such as tolerance, dependence, and addiction, as there are many misconceptions related to these concepts which may contribute to the inadequate treatment of pain (Berger et al., 2013). Key concepts associated with opioid use are defined in Table 1.

Opioids

Opioids are a group of controlled substance analgesics that are commonly prescribed for moderate to severe pain control. Opioids function by binding to mu-opioid receptors that are spread diffusely throughout the central nervous system (CNS). By attaching to a receptor in the CNS, they reduce or block the pain signal to the brain, thereby altering pain perception and response to pain. Opioids can also affect receptors in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract, so beyond their clinical uses for pain management, they are occasionally used to treat diarrhea and cough. Opioids are classified as agonists, partial agonists, and mixed agonist-antagonists. Opioid antagonists may be used to counteract the adverse effects of opioids (Berger et al., 2013).

Opioid Agonists

Opioid agonists are drugs that produce a maximum biologic effect between receptor binding and response (Berger et al., 2013). Opioids vary in the ratio of their analgesic potency and their potential for respiratory depression. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS, 2019), the most common opioid agonists prescribed for moderate or severe pain include:

- Hydrocodone (Vicodin, Lortab, Norco): found only in combination products, usually combined with acetaminophen; may be oral tablet formulation or liquid cough syrup;

- Oxycodone (Roxicodone, Oxycontin): available as immediate release (IR) or extended release (ER) formula, fast onset, available in oral tablet or solution form;

- Morphine sulfate (Roxanol, MS Contin): available as an IR or ER formula, as well as parenteral and oral formulations;

- Oxymorphone (Opana, Opana ER): available as an IR or ER formula, long half-life;

- Hydromorphone (Dilaudid, Exalgo ER): derivative of morphine, but with a faster onset; available as an oral tablet, liquid, suppository, and parenteral formulations; available as an IR or ER formula (USDHHS, 2019).

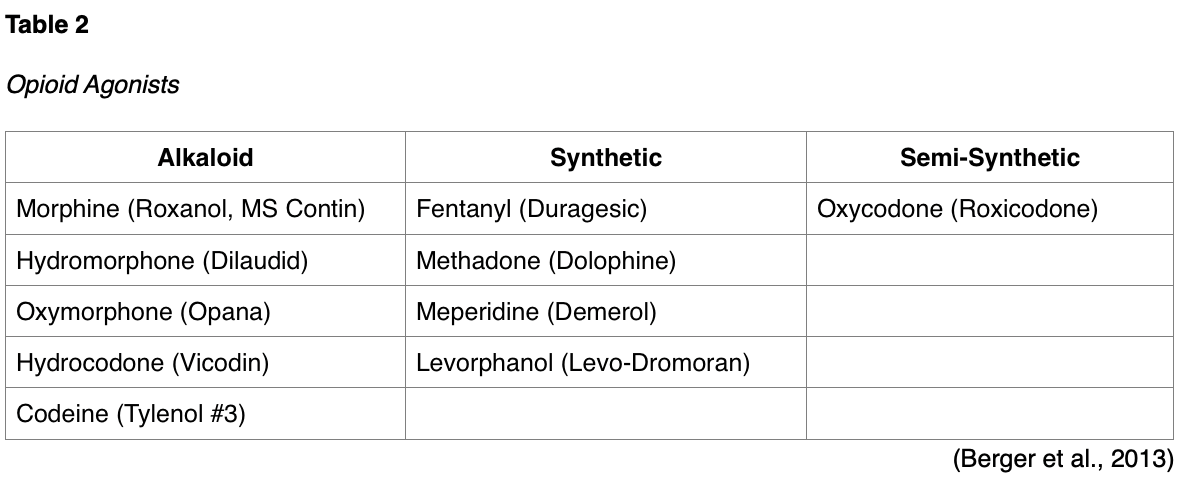

They are classified into the following categories: naturally occurring alkaloids (derived from the opium poppy plant), synthetic (human-made), and semi-synthetic forms. These and other common types of opioid agonists are listed according to each of these categories in Table 2.

Fentanyl (Duragesic) is a highly lipid-soluble opioid that can be administered through various parenteral administration modalities, including transdermal, transmucosal, intranasal, spinal, and intravenous through patient-controlled devices. Fentanyl dosing is in micrograms due to its high potency, as it is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine sulfate (Roxanol, MS Contin). Methadone (Dolophine) is a long-acting opioid that has particular importance in neuropathic pain. It has a prolonged plasma half-life that allows for a once every 8-hour dosing schedule. However, prescribers must be able to provide evidence of appropriate education to manage this drug. The half-life of methadone (Dolophine) is significantly longer than morphine (8 to 59 hours), with lipophilic storage, so great care should be taken with this drug to treat pain safely. However, it is considerably cheaper than other medications, and is widely dispensed in substance use disorder clinics as a component of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid-dependent patients. Since it is long-acting, it can delay the opioid withdrawal symptoms that patients experience when taking short-acting opioids. Therefore, it allows time for detoxification (Hudspeth, 2016). Codeine is a relatively weak opioid agonist, most commonly used to treat mild to moderate pain or cough. It can be administered alone or in combination with acetaminophen (Tylenol-Codeine #3), or as part of cough and cold formulas. Adverse reactions to opioid agonists include respiratory depression, drowsiness, mental confusion, nausea/vomiting, dizziness, headache, fatigue, pruritus, pinpoint pupils, urinary retention, and constipation. Since these drugs can induce euphoria, especially when taken in higher doses than prescribed or ingested via snorting or injection, they are at high risk for abuse and addiction. Long-term use of these medications infers a risk of drug tolerance and hyperalgesia, which is increased sensitivity to pain caused by damage to nociceptors or peripheral nerves (US Food & Drug Administration [FDA], 2018a).

Partial Agonists

Partial agonists are opioids that have a submaximal response between receptor binding an

...purchase below to continue the course

Mixed Agonist-Antagonists

An agonist-antagonist refers to an opioid with mixed actions. These drugs produce different activities at different receptors, acting on one opioid receptor to create a response, and binding to another receptor to prevent a response. Medications in this class demonstrate varying activity depending on the receptor that is targeted and the dose. Some examples of agonist-antagonists include pentazocine/naloxone (Talwin) and butorphanol (Stadol). Pentazocine/naloxone (Talwin) is used to treat moderate to severe pain and it includes two medications. It acts by binding to and activating specific opioid receptors while simultaneously blocking the activity of other opioid receptors. The naloxone component of the medication helps to prevent misuse of the medication. Pentazocine (Talwin) is not available in the US as a single agent, and instead is only available in the combination form with naloxone. Butorphanol (Stadol) is a mixed opioid agonist-antagonist available as a spray for the treatment of migraine headaches. Similar to partial agonists, agonist-antagonist opioids have a ceiling effect. Therefore, they offer lower analgesic efficacy and heightened risk for psychotomimetic or psychotogenic effects, or symptoms of psychosis, such as hallucinations and delirium (Berger et al., 2013).

Opioid Antagonists

Opioid antagonists compete with opioids at opioid receptor sites and are drugs used to reverse the acute adverse effects, primarily respiratory depression, caused by opioids or to treat opioid use disorder long-term. Naloxone (Narcan) is the most widely used opioid antagonist, as it is FDA-approved for the use of an opioid overdose. It is highly effective in reversing an opioid overdose and respiratory depression and is dispensed in intravenous (IV), intramuscular (IM), subcutaneous (SC), and intranasal (IN) formulations. When administered intravenously, effects begin almost instantly and last for about an hour. Still, the dose should be titrated to achieve the reversal of respiratory depression without full reversal of the analgesic effects. Rapid infusion of the medication should be avoided to reduce the risk of hypertension, tachycardia, nausea, and vomiting. Vital signs should be monitored, especially respirations, and naloxone administration repeated until the manifestations of opioid toxicity have subsided (Theriot et al., 2019). With IM and SC administration, the drug takes effect in two to five minutes and lasts for several hours. These administration routes are most commonly used by emergency medical services (EMS) personnel and civilians responding to opioid overdose in the community. According to the National Emergency Medical Services Information System, the rate of EMS naloxone administration events increased 75.1%, from 573.6 to 1,004.4 administrations per 100,000 EMS events from 2012-2016, which corresponds well with 79.7% increase in opioid overdose mortality during those same years (Cash et al., 2018). Many EMS personnel are moving toward intranasal administration which is viewed as providing important advantages over injection when responding to overdose patients in the community. The safety profile of intranasal formulations appears to be no different from the injection formulation in the treatment of opioid overdose. Krieter and colleagues (2016) compared the pharmacokinetic properties of intranasal naloxone (2-8 mg) delivered in low volumes (0.1-0.2 mL) to the approved (0.4 mg) IM dose. All doses of intranasal naloxone resulted in plasma concentrations and areas under the curve greater than observed following the intramuscular dose, and the time to reach maximum plasma concentrations was not different following intranasal and intramuscular administration (Krieter et al., 2016).

Naloxone (Narcan) has become increasingly available to the public, as the prescribing and dispensing of it has become a central part of the public health response to the opioid overdose epidemic. In addition, the majority of states now allow naloxone to be purchased from a pharmacy without a prescription. Prescribers are advised to consider prescribing a concurrent prescription for naloxone (Narcan) for patients who are at high risk for intentional or accidental overdose. Those considered to be at the highest risk include patients who meet any of the following criteria:

- Doses of > 90 MME/day;

- Chronic opioid use;

- Concurrent use of benzodiazepines;

- Personal history of substance abuse/opioid misuse disorders;

- Current treatment for substance abuse/opioid misuse disorders;

- Family history of substance abuse;

- Patients being treated with opioids who live in isolated or rural areas;

- Patients with chronic respiratory disease;

- HIV/AIDS;

- Chronic renal, hepatic, or cardiac disease;

- Current or past history of depression or other serious mental health conditions (Webster, 2017).

Serious adverse effects of naloxone (Narcan) are rare, and usually, the benefit of using it for an overdose outweighs the risk for adverse effects. However, it can induce acute opioid withdrawal symptoms such as tachycardia, agitation, vomiting, body aches, and convulsions. Naloxone has no reversal effect on tramadol (Ultram), alcohol, or other CNS depressants such as benzodiazepines (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2018).

Naltrexone (Vivitrol, Revia) is an opioid antagonist that is used to treat substance use disorders, namely alcohol and opioids. It is also used to treat postoperative respiratory depression due to the use of opioids during the operative period. When used for opioid addiction, its purpose is to prevent euphoria and the desire to use opioids. The patient should be opioid-free for 7 to 10 days before beginning the medication to prevent opioid withdrawal syndrome. It is available as a long-acting injection and can be prescribed by any licensed prescriber (Theriot et al., 2019).

Opioid Routes of Administration

Opioids can be administered orally, intravenously, intramuscularly, transdermally, and subcutaneously, and they are supplied in short-acting and long-acting preparations. Regardless of the route of administration, education regarding the adverse effects as well as risks and benefits is vital in terms of understanding clinical indications and patient outcomes. The oral route for administration of analgesics is generally preferred for patients whenever possible due to ease of administration, cost-efficacy, and monitoring. However, the duration of action for the majority of IR or short-acting oral opioids is only about four hours. ER formulations can usually provide pain control for eight to twelve hours or more. Intranasal analgesic administration is advantageous because the medication is rapidly absorbed. Topical analgesics are applied directly to the skin and are absorbed by vascular uptake. This route may be used to reduce pain during a painful procedure, such as a lumbar puncture. Lidocaine (Lidocaine viscous) is available as a gel or cream and is commonly used for dental procedures or other superficially invasive procedures such as skin biopsies due to its rapid onset. As highlighted earlier, lidocaine (Lidoderm) is also available as a topical patch to be applied to intact skin. The transdermal route for the administration of analgesics may also be used to treat chronic pain. Long-acting medication that is absorbed through the skin can provide pain control for several hours to days. Transdermal fentanyl (Duragesic) is indicated for patients who have severe pain and are opioid-tolerant (Berger et al., 2013).

The transmucosal route for the administration of analgesics is frequently used for hospice patients experiencing breakthrough pain. The oral mucosa is highly vascular, providing rapid absorption. The rectal route for administration of analgesics can also be used when rapid pain control is desired; the mucous membranes of the rectum are highly vascular, causing quick absorption of the medication. This route is helpful for unconscious patients, those who have difficulty swallowing, or are experiencing nausea and vomiting. When epidural analgesia is used, an anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist inserts a catheter into the epidural space along the spine. An analgesic such as morphine (Roxanol, MS Contin) or fentanyl (Duragesic) is infused through the catheter. The patient should be monitored closely for respiratory depression, excessive sedation, hypotension, bradycardia, and urinary retention. The use of other opioids or CNS depressants should be avoided during the use of epidural analgesia. The healthcare team should closely monitor the patient and be prepared to administer naloxone for symptoms of respiratory depression or excessive sedation (Berger et al., 2013).

Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA)

PCA is a medication delivery system that allows patients to selfadminister safe doses of opioids and is almost exclusively used in acute inpatient hospital and inpatient hospice settings. Some of the fundamental principles regarding the use of a PCA are represented in the bullet points below.

- A PCA provides small, frequent dosing to ensure consistent plasma levels;

- Patients have less lag time between an identified need and the delivery of medication, which increases their sense of control and can decrease the amount of medication needed;

- Morphine (Roxanol, MS Contin), hydromorphone (Dilaudid), and fentanyl (Duragesic) are typical opioids for PCA delivery;

- Patients should be encouraged to let their healthcare team know if using the PCA pump does not adequately control the pain;

- It is widely recommended that caregivers and family members are educated on the potential for inadvertent overdosing when the PCA button is pressed by anyone other than the patient, also called PCA by proxy;

- Clear institutional criteria regarding which patients should receive PCA and careful patient assessment throughout PCA use is essential to ensure patient safety (Berger et al., 2013).

Opioid Assessment

There are several tools available for assessing opioid risk. To balance effective pain management and safety when prescribing opioids, evidence-based guidelines recommend that clinicians who prescribe opioids use risk assessment instruments in patients before starting opioid therapy. The most common tools used include:

- Opioid Risk Tool (ORT)

- Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R)

- Screening Instrument for Substance Abuse Potential (SISAP)

- Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk, and Efficacy Score (DIRE) (Cheattle, 2019).

The ORT, SOAPP-R, and SISAP are self-administered tools that can be completed by the patient. The ORT and SISAP are five-item questionnaires used to predict the risk for opioid misuse. The SOAPP-R is a 24-item instrument constructed to predict the development of problematic drug-related behaviors (PDRB). The DIRE is an instrument administered by the clinician and predicts the efficacy of analgesia and adherence with long-term opioid therapy (Cheattle, 2019).

Stepwise Approach to Opioid Use

Best practice guidelines recommend that reasonable non-opioid treatments such as NSAIDs or acetaminophen (Tylenol) should be trialed and failed before opioids are initiated (Qaseem et al., 2017). If opioids are prescribed for acute pain, CDC (2016) prescribing guidelines advise limiting the initial prescription to between three and seven days. The initial opioid prescription should be considered a trial, with a follow-up appointment scheduled at a predetermined time to review the effectiveness and success based on established treatment goals (CDC, 2016). Moderate pain can often be managed with weaker opioids such as codeine (Tylenol #3) or tramadol (Ultram). Treatment for severe pain should start with a stronger oral opioid such as hydrocodone (Vicodin), oxycodone (Roxicodone), morphine sulfate (Roxanol, MS Contin), or hydromorphone (Dilaudid). Fentanyl (Duragesic) and methadone (Dolophine) should be avoided as first-line options due to their dosing challenges (lipid-soluble, high potency, long half-life). IR medications with a half-life of two to four hours should be started initially with opioid-naive patients until the dose is stabilized. Dose adjustments may be necessary as often as every two to three days. ER or long-acting (LA) formulas with a half-life of 8-12 hours in the same family are commonly added later if long-term use is required (Pain Assessment and Management Initiative [PAMI], 2019).

According to the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (2017), the pharmacological treatment of chronic pain (excluding cancer patients and end-of-life care) treatment, like acute pain, should always start with nonopioid treatment options as above (Manchikanti et al., 2017). When initiating opioid therapy for the management of pain severe enough to require daily, around-the-clock, long-term opioid treatment, it is highly recommended that the lowest dose possible is given. Treatment should begin with an IR opioid and include a LA/ER later if indicated (Federation of State Medical Boards [FSMB], 2017). The lowest effective dose of IR opioids should be used initially, avoiding ER or LA versions until a stable dosage has been established. The dose should be slowly titrated with the priority of treatment to administer the lowest dose that provides relief from pain with the fewest adverse effects. Every opioid works a little differently; therefore, each must be titrated to meet the needs of the patient while ensuring toxicity and harm from adverse effects are minimized (Manchikanti et al., 2017).

Providers should reassess the risks and benefits of treatment when prescribing more than 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day and should avoid (and carefully justify) prescribing more than 90 MME/day. According to the CDC’s Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain (2016), the risk of overdose is increased by at least twice in patients taking 50 MME/day or more, as compared to patients taking less than 20 MME/day. 50 MME is about 50 mg of hydrocodone or 33 mg of oxycodone per day. Prescribers should become familiar with and maintain access to a current MME calculator to use with dosage changes and for transitions between different medications to establish equivalent dosages. Several dose calculators are available free of charge online, including on the CDC website and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. However, these calculators have their limitations and complicated exceptions (Fudin et al., 2018). A follow-up appointment within one to four weeks of starting opioids or dose increases is recommended to assess benefits and any harms, and once stable, follow-ups should occur every three months (CDC, 2016). If, at any point, the risks or harm outweigh the benefits, opioids should be tapered to a lower dose or gradually discontinued and other treatments optimized (Manchikanti et al., 2017). Assessing the patient’s pain level, functional abilities, and quality of life will indicate whether or not the current treatment plan is performing successfully at each of these visits (FSMB, 2017).

Complications of Opioid Use

There are several adverse effects associated with opioid use, which vary in degrees of severity based on the dose and potency of the medication, route of administration, and if the medication is self-administered or administered by a nurse or other caregiver. Patients on opioid therapy should be monitored for any of the following adverse effects:

- Sedation, respiratory depression, and coma can occur as a result of an opioid overdose. Since sedation always precedes respiratory depression, the patient's level of consciousness should be monitored closely so proper safety precautions can be promptly taken. To reduce the risk of overdose when administering opioids, the following actions are recommended:

- Identify highrisk patients (older adult patients, those who are opioidnaive);

- Assessment should focus on the patient's respiratory rate, depth, and regularity before and following administration of opioids (especially for patients who have minimal prior exposure to opioid medications);

- Initial treatment of respiratory depression and sedation is generally a reduction in the opioid dose. Carefully titrate patient dose while closely monitoring respiratory status;

- If necessary, slowly administer diluted naloxone to reverse opioid effects until the patient can deep breathe with a respiratory rate of at least 8/min;

- Alternatively, stop the opioid and give the antagonist naloxone if respiratory rate is below 8/min and shallow, or the patient is difficult to arouse;

- Use a sedation scale in addition to a pain rating scale to assess pain, especially when administering opioids.

- Orthostatic hypotension: advise patients to sit or lie down if lightheadedness or dizziness occurs. Instruct patients to avoid sudden changes in position by slowly moving from a lying to a sitting or standing position.

- Urinary retention: monitor intake and output; assess for bladder distention, administer bethanechol (Urecholine) to relieve retention, and try noninvasive actions before catheterizing.

- Nausea/vomiting: administer antiemetics, advise patients to lie still and move slowly, and eliminate odors.

- Constipation: a preventative approach should be taken for all patients’ prescribed opioid therapy, including monitoring of bowel movements, increasing fluids and fiber intake, encouraging exercise, providing stool softeners and stimulant laxatives, and administering enemas, if clinically indicated.

- Opioid toxicity and overdose: manifestations of opioid toxicity are respiratory depression, coma and pinpoint pupils (also referred to as the opioid triad) (Berger et al., 2013; Fine et al., 2015).

Opioid Use in the Older Adult

Special considerations should be applied when prescribing opioids for populations at potentially higher risk for harm, such as older adults (over 65), those with renal or hepatic insufficiency, and those who are pregnant. Advancing age is often accompanied by physiological changes that affect the absorption, metabolism, and excretion of medications. Older adults may be at increased risk for falls and fractures related to opioids, and clinicians are advised to consider a falls-risk when selecting and dosing potentially sedating medications such as tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, or opioids (CDC, 2016). When less harmful alternative pharmacological modalities are ineffective, prescribers are encouraged to initiate therapy with controlled substances at the lowest possible dose and gradually increased only as needed (start low and go slow). It is also advised when prescribing opioids to older adults to initiate a bowel program to prevent constipation (CDC, 2016). In the most recent version of the American Geriatric Society BC, they state that opioids should be avoided in older adults with a history of falls or fractures (Terrery & Nicoteri, 2016).

Opioid Use During Pregnancy

While opioid use in pregnancy is not well studied, use can be associated with risks to both the mother and the fetus (CDC, 2016). In 2014, the FDA removed the older system of ranking medications for pregnant women (Category A, B, C, D, and X), and now requires detailed specific information about pregnancy safety (including during labor and delivery), safety while breastfeeding, and safety for females and males of reproductive potential (FDA, 2018a). Some studies have shown an association of opioid use in pregnancy with congenital disabilities, including neural tube defects, congenital heart defects, preterm delivery, poor fetal growth, stillbirth, and potential for neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (CDC, 2016). Opioids are excreted in breastmilk and increase the risk for CNS and respiratory depression in the infant if taken by the mother while breastfeeding. These risks can be minimized by using the lowest effective dose to achieve pain control. The patient should be well informed of all of the potential risks before issuing any opioid or controlled substance prescriptions. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) can be used during pregnancy and while breastfeeding relatively safely. NSAIDs should be avoided in pregnant patients, especially during the first trimester and after 30 weeks' gestation, due to the risk of bleeding and risk of premature ductal closure. NSAIDs appear safe to use during breastfeeding, however (FDA, 2018a).

Cancer Patients and Pain Management at the End-of-Life

The treatment of cancer pain is extremely complex, and the patient's disease prognosis, concurrent medications, and individual goals of care should be carefully considered for all decision-making (Hudspeth, 2016). The treatment of pain within the specialty care of terminally ill patients does not typically conform to the aforementioned standard regulations. Within the care of these patients, there is less concern for misuse, abuse, or addiction, and more focus can be placed on effective pain relief (CDC, 2016). Concerns within these populations continue to be overdose, respiratory depression, and potential loss of consciousness or hastening of end-of-life. According to the National Consensus Project (NCP, 2018) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, medications should be increased gradually and only as tolerated, with the full consent of the patient or their proxy medical decision-maker/guardian or via an intact living will or advance directive. The patient and/or caregivers should be fully informed of the potential risks of increased opioid doses. If the patient and family prioritize pain relief over the length of life, that decision should be accepted and respected by the care team. It is generally accepted that clinicians should never withhold needed pain medication from terminally ill patients for fear of hastening death if they have received informed consent from the patient to do so. Loss of consciousness should not always be assumed to be directly caused by high doses of opioid painkillers in the dying patient if those doses have been stable or slowly increasing over time, especially in chronic cancer pain (NCP, 2018).

Opioid Abuse and Misuse

Drug overdose is a leading cause of accidental death in the US, with opioids being the most common drug. Increased prescription of opioid medications for the management of pain over the last two decades has led to the widespread misuse of both prescription and non-prescription opioids, igniting the nationwide public health emergency known as the Opioid Epidemic (Schiller et al., 2019). According to the CDC (2019a), more than 702,000 people died from an opioid overdose between 1999 and 2017. Data acquired from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health conducted by SAMHSA (2018b) disclosed that more than 11.4 million people misused prescription opioids, and 2.1 million had an opioid use disorder. The most commonly abused medications were hydrocodone products, and 62.6% of users reported misuse as a means to manage physical pain, whereas 13.2% reported misuse to 'feel good' or 'get high.' In terms of how the medication was acquired, greater than 53% reported obtaining it through a relative or friend, whereas 34.6% had a valid prescription written by a licensed prescriber. The number of people who misused prescription pain relievers for the first time in 2017 averaged 5,500 initiates per day (SAMHSA, 2018b). Currently, an estimated 130 people die each day from an opioid overdose, and these numbers continue to rise (CDC, 2019b).

Contributing and Risk Factors for Potential Misuse/Abuse

The progressive rise in prescription drug misuse/abuse across the US is a byproduct of the complex interplay of many contributing factors. However, the CDC (2019a) cites the increased prescribing of opioid analgesics as the most preeminent contributing factor for the significant increase in drug availability, and in turn, misuse/abuse potential. According to the USDHHS (2019), additional societal and environmental factors include aggressive marketing by the pharmaceutical industry, the explosion of illegal web-based pharmacies that disseminate these medications without proper prescriptions and surveillance, as well as greater social acceptability for medicating a growing number of conditions.

Personal risk factors for potential drug misuse/abuse include untreated psychiatric disorders, younger age, past or current substance abuse (including alcohol and tobacco use), family history of drug abuse, as well as family or societal environments that encourage these behaviors (Webster, 2017). While prescription drug abuse can happen at any age, data reveals it more commonly begins in teens or young adults. However, in contrast, opioid mortality prevalence is higher in those who are middle-aged with comorbid substance abuse and psychiatric conditions (SAMHSA, 2018b). Prescription drug abuse in older adults is a growing problem, especially when combined with alcohol. Having multiple health problems and taking multiple drugs can put the older adult population at risk of misusing drugs or becoming addicted to opioids. Also, a lack of knowledge about prescription drugs and their potential harm heightens the risk within this population (NIDA, 2018b).

Opioid Use Disorder (OUD)

OUD is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) as a problematic pattern of opioid use that leads to clinically significant and severe impairment or distress. OUD may be classified as mild, moderate, or severe, and is characterized by two or more of the following symptoms within a 12-month period:

- Loss of control

- Opioids taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended;

- Persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control opioid use;

- Excess time spent in activities to obtain the opioid, use the opioid, or recover from its effects.

- Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use opioids.

- Social consequences

- Continued use despite negative consequences, such as failure at work, school, or home;

- Continued use despite persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of opioids;

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities that are given up or reduced because of opioid use.

- Risky use

- Recurrent use in dangerous and physically hazardous situations.

- Physical or psychological problems

- Continued opioid use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance;

- Exhibits symptoms of tolerance and/or withdrawal (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013).

The Safe and Effective Prescribing of Opioids

Opioids, as well as all other types of controlled substances, are classified according to categories or "schedules," based on the perceived risk of addiction as outlined by the DEA. There are several responsibilities to providing safe, effective care for the patient who is receiving an opioid medication. State laws, regulations, and policies further delineate prescriber responsibilities surrounding the prescribing and dispensing of controlled substances. In 2017, the US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS, 2017) increased grant funding toward the development of novel strategies to impede this growing and deadly problem. These efforts have brought a new level of urgency to the matter, with heightened surveillance, restriction, and monitoring of patients on long-term opioid therapy. To prescribe high-risk medications, all providers must be registered with the DEA and be granted prescriptive authority. Prescribers must also understand the legislative details surrounding prescribing and monitoring of opioids in state. It is equally imperative for healthcare professionals to remain vigilant in screening for the signs and symptoms of misuse and abuse (Schiller et al., 2019).

As part of the national movement to mitigate the opioid epidemic, the vast majority of states (49 states, Washington DC, and Guam) have now established statewide electronic databases or prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) to track and monitor opioid prescriptions. A PDMP is a statewide electronic database which collects designated data on controlled substances dispensed to, or for, each patient. The intent is to improve opioid prescribing, inform clinical practice, and protect patients at high risk. PDMPs are housed and operated by state regulatory, administrative, or law enforcement agencies. The housing agency disseminates information from the database to individuals who are authorized under state law to receive the information for purposes identified by state law. States arrange individual systems to track and monitor prescriptions, but the details about use, access, which drugs are included, and the regulations and implications for prescribers vary greatly from state to state. Most states have a method by which prescribers can access their patient's records in other or neighboring states, in addition to their own. The key to the efficacy of PDMP systems is the mandate that all providers check the system before initiating opioid therapy. Reviewing the patient's history of controlled substance prescriptions using the PDMP database helps to determine whether the patient is already receiving opioids or potentially dangerous combinations that place them at risk for overdose. Differences exist between the states regarding how frequently providers should monitor this system, and which controlled substances are included. Reporting systems help reduce the diversion of illegitimate opiate prescriptions (CDC, 2017).

Once opioid therapy is initiated, prescribers have a responsibility to assess and monitor for potential signs of opioid misuse throughout treatment. There are several risk assessment instruments available to assist prescribers with the ongoing monitoring process. Some of the most commonly used tools include the following:

- Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire-Patient (PDUQ-P);

- Pain Medication Questionnaire (PMQ);

- Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM);

- Addiction Behavior Checklist (ABC);

The PDUQ-P, PMQ, and COMM are patient-administered tools, whereas the ABC is a clinician-completed questionnaire (Cheattle, 2019).

In addition to the use of monitoring instruments, other risk mitigation strategies include having patients return for more frequent monitoring intervals and performing random pill counts. Some states, such as Tennessee, require that providers continually monitor the patient for signs of abuse, misuse, or diversion by performing unannounced urine drug testing (UDT), at least twice per year. Also, the CDC (2016) recommends that clinicians should perform UDT before starting opioid therapy and at least once annually to assess for prescribed medications as well as other controlled prescription drugs and illicit drugs.

Patient-Provider Agreements and Opioid Contracts

Some states have laws mandating the use of patient-provider agreements (PPA) or opioid contracts. PPAs are written agreements between prescribers and patients outlining and clarifying the conditions for prescribing opioids over the long term, and they can help formulize safer approaches to opioid prescribing. The contract underscores the critical importance of the proper use of prescribed pain medications, along with outlining the standards of care and the expectations of treatment (CDC, 2017). It promotes collaboration and mutual commitment from both parties, sets realistic expectations with measurable goals for therapy, and also states reasons for which the agreement may be terminated. These contracts should address the potential adverse effects, possible overdose, respiratory depression, development of physical dependence or tolerance, drug interactions, inadvertent ingestion by children or others, and drug misuse or abuse by the patient, as well as household contacts or friends. Furthermore, prescribing policies should be clearly defined, including the number and frequency of refills, policy on early refills, and procedures for lost, damaged, or stolen medications. If UDTs or pill counts are to be performed periodically, this should be included in the agreement, as well as how medication refills and changes should be requested and obtained by the patient and handled by the office staff and providers. While not all state laws require the use of a PPA, they are highly recommended, and there are various sample documents and resources available for clinicians to use (CDC, 2017). One such document is available to the public for use through the NIDA (n.d.) website, drugabuse.gov.

Documentation

Documentation is critical when prescribing controlled substances, both for safety and legal reasons. Documentation in the medical record should be clear, concise, and include all details outlining dose adjustments or medication changes with associated justifications and equivalency calculations, the effectiveness of treatments based on consistent pain and other assessments repeated at each visit, as well as any adverse effects and related therapies. Documentation should also specify if the patient is adhering to treatment plans as outlined in the PPA and include results of any UDTs or pill counts. Any concerning or aberrant behavior should be carefully documented with as much detail as possible. Interviews with family members and caregivers can also be included in documentation records for those same reasons with a clear plan for resolution and/or future monitoring (PAMI, 2019). Any letters sent to patients should be included in the patient's medical record, and any phone calls made or received should be carefully documented by office staff. Document every time PDMP reports are reviewed and any concerning findings. A decision to terminate care needs to be documented thoroughly (Hudspeth, 2016).

Termination of Chronic Opioid Therapy

As with the treatment of any medical condition, the goal is to restore health and resume pre-illness activities of daily living; the same is true for termination of chronic opioid therapy. Termination is an intentional process that occurs when a patient has achieved most of the goals of treatment, and/or when therapy must end for other reasons. According to the FSMB (2017), continuation, modification, or termination of opioid therapy for pain is contingent on "the clinician's evaluation of (1) evidence of the patient's progress toward treatment objectives and (2) the absence of substantial risks or adverse events, such as signs of substance use disorder and/or diversion" (FSMB, 2017, p.11).

The most common reasons for termination of long-term opioid therapy include the achievement of goals of therapy, treatment policy nonadherence, follow-up nonadherence, or concern for misuse/abuse or diversion (McDonald, 2015). Other reasons include resolution of the underlying condition, intolerable adverse effects, inadequate analgesic effects, and a lack of improvement in the patient’s quality of life (FSMB, 2017). Appropriate termination helps to avoid the betrayal of trust and abuse of power, prevents harm, and conveys caring. The PPA plays a critical role in this process, and therefore termination must be addressed comprehensively in the initial contractual agreement and updated accordingly. Termination always carries the risk of exposing the patient to severe pain and sending the wrong message to the patient (McDonald, 2015). A carefully structured taper should be given to anyone who is potentially physically dependent on their opioid to avoid withdrawal symptoms. Otherwise, a referral to an addiction specialist may be required for those on very high doses of opioids. The provider should reassure the patient that this change does not indicate the end of their treatment, which will proceed with other modalities or through another provider if necessary (FSMB, 2017).

Strategies for termination of chronic opioid therapy include the following:

- Establish open, honest communication and dialogue with the patient from the point of the initial consultation;

- Comprehensively address termination in the informed consent and PPA process and readdress or refer back to as necessary during the duration of therapy;

- Set realistic, time-sensitive goals at the beginning of treatment;

- Balance clinical judgment and individualization;

- Incidents or events that cause concern regarding a pain agreement need to be interpreted within the context of the whole patient;

- Opioid taper: tapering should be performed after discussion with the patient. There is no “one way” to taper a patient, yet generally, the longer the patient has been on opioids, the longer it will take for a successful taper;

- Avoid terminating the relationship when a patient is in crisis without referral to a specialized facility and a warm handoff to the receiving provider. If a patient is terminated while in crisis, it might reasonably be considered abandonment and escalate abhorrent behaviors;

- As part of the termination preparation process, the patient should be given information about other available resources (community resources, support groups, nonpharmacological pain modalities), and document that resources have been provided (McDonald, 2015).

The evidence regarding how best to taper long-term opioid users with chronic noncancer pain is not robust. Most recommend a modest reduction in dosage (10%) every week, but a patient who has been on their opioid medication for years may require a 10% reduction every month in order to avoid withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms can be managed with a2-adrenergic agonists such as clonidine (Catapres) or tizanidine (Zanaflex). An alternative is to transition the patient to a partial agonist, such as buprenorphine (Suboxone), or a different opioid agonist, such as methadone (Dolophine), and then taper at the above referenced rate to avoid withdrawal symptoms. However, as previously mentioned, both buprenorphine (Suboxone) and methadone (Dolophine) require specialized training and/or certification to prescribe (Berna, 2015).

The APRN Role in Ensuring Adequate Pain Management

The APRN should take a proactive approach by assessing and reassessing patients for pain frequently. Ensuring analgesics are prescribed and given before pain becomes too severe promotes adequate pain control. For hospitalized patients, the APRN should instruct patients to report developing or recurrent pain early and not wait until the pain is severe to ask for their as-needed pain medications. It takes less medication to prevent pain than to treat pain. The APRN should explain misconceptions and myths about pain to reduce the patient’s fear and anxiety regarding pain medication. This education can help promote acceptance and compliance by patients who are reluctant to take opioids due to concerns related to addiction. For patients with chronic and uncontrolled pain, administer analgesics around the clock rather than as needed by prescribing a LA or ER opioid analgesic (including the transdermal route) (CDC, 2016).

Providing adequate pain management without promoting OUD is a challenge for health care providers. Concerns about OUD should not be minimized. To address the current epidemic of opioid use disorder in the U.S., the FDA and the CDC have developed action plans to reduce the impact of this public health crisis. The FDA's (2018b) opioid action plan includes:

- Expanding advisory committees to study new opioids that do not have abuse properties;

- Establish a more extensive framework for pediatric opioid medication labeling;

- Create additional labeling for ER/LA opioids to include more warnings and safety information;

- Charge pharmaceutical companies with the task of performing more post-market research on the long-term impact of using ER/LA opioids;

- Increase training to providers on pain management and safe prescribing of opioids;

- Encourage pharmaceutical companies to develop generic abuse-deterrent products for pain;

- Expand over-the-counter access to intranasal naloxone (FDA, 2018b).

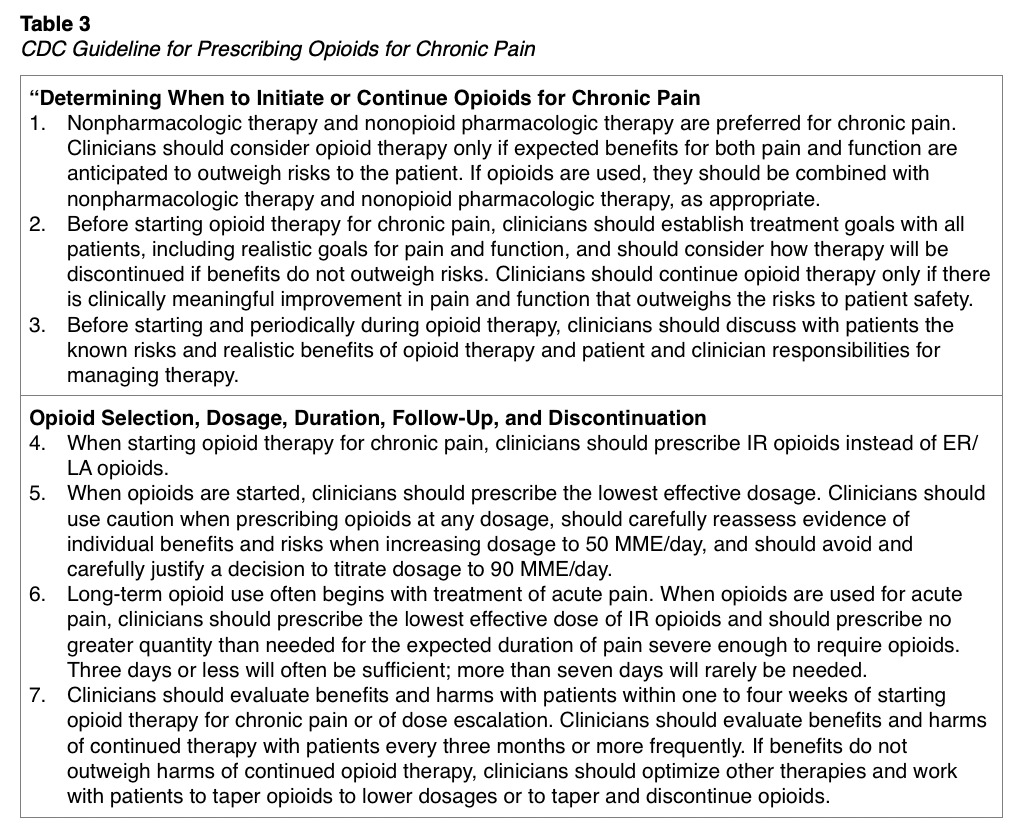

The CDC's Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain (CDC, 2016) includes guidance for providers when initiating or continuing opioid use for a patient who is experiencing chronic pain. The guidelines pose twelve key Category A recommendations which are listed in Table 3.

Anxiolytics

Anxiolytics, or antianxiety medications, are commonly prescribed to treat the anxiety that accompanies acute pain or anxiety resulting from fluctuations in chronic pain. Most anxiolytics are classified as CNS depressants; they function by inhibiting the activity of the neurotransmitter GABA and thereby producing a drowsy or calming effect. Benzodiazepines are one of the most common classes of anxiolytics used in patients for pain management. These include medications such as lorazepam (Ativan), alprazolam (Xanax), and triazolam (Halcion). This class of drugs are categorized as schedule IV medications and are usually prescribed to treat generalized anxiety, panic attacks, acute stress reactions, muscle spasms (diazepam [Valium]), seizure disorders (clonazepam [Klonopin]), and sleep disorders. In general, these drugs require great caution and monitoring. They are indicated for short-term use only due to the very high risk of tolerance, dependence, and addiction. Concurrent use of benzodiazepines and opioid pain medications requires heightened caution due to the additive risks of interaction between these two classes of controlled substances (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2018a). The 2015 American Geriatric Society Beers Criteria (BC) of potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults publishes medications that should be avoided. They suggest that benzodiazepines should be avoided for insomnia, agitation, or delirium due to fall risk and high rate of physical dependence (Terrery & Nicoteri, 2016). Benzodiazepines should also be avoided in pregnant and breastfeeding patients, as they are known to cross the placenta and are excreted in breastmilk. They have been shown to increase the risk of congenital abnormalities, primarily if used in the first trimester (FDA, 2018a).

For additional information regarding the opioid epidemic, please refer to the NursingCE.com course entitled, A Nurse's Role in the American Opioid Epidemic (1-credit hour), and Safe and Effective Prescription of Controlled Substances Nursing CE course (1.5-credit hours).

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders, DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Berger, A. M., Shuster, J. L., & Von Roenn, J. H. (2013). Principles and practices of palliative care and supportive oncology (3rd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Berna, C., Kulich, R. J., & Rathmell, J. P. (2015). Tapering long-term opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90(6). 828-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.04.003

Cash, R. E., Kinsman, J., Crowe, R. P., Rivard, M. K., Faul, M., & Panchal, A. R. (2018). Naloxone administration frequency during emergency medical service events — United States, 2012–2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(31), 850-853. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6731a2

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). CDC guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fmmwr%2Fvolumes%2F65%2Frr%2Frr6501e1er.htm

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). What states need to know about PDMPs. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdmp/states.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Using naloxone to reverse opioid overdose in the workplace: Information for employers and workers. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2019-101/

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019a). Drug overdose deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019b). America’s drug overdose epidemic: Data to action. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/prescription-drug-overdose/index.html

Cheattle, M. (2019). Risk assessment: Safe, opioid prescribing tools. https://www.practicalpainmanagement.com/resource-centers/opioid-prescribing-monitoring/risk-assessment-safe-opioid-prescribing-tools

Drug Enforcement Administration. (n. d.). Diversion Control Division. Retrieved February 1, 2020 from https://www.dea.gov/diversion-control-division

Federation of State Medical Boards. (2017). Guidelines for the chronic use of opioid analgesics. https://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/opioid_guidelines_as_adopted_april-2017_final.pdf

Fine, P., & Cheatle, M. (2015). Common adverse effects and complications of long-term opioid therapy. Pain Medicine, 16 (1), S1-S2. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12925

Fudin, J., Raouf, M., Wegrzyn, E. L., & Schatman, M. E. (2018). Safety concerns with the Centers for Disease Control opioid calculator. Journal of Pain Research, 11, 1–4. http://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S155444

Hudspeth, R. S. (2016). Safe opioid prescribing for adults by nurse practitioners: Part 2. Implementing and managing treatment. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners,12(4), 213-220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.11.032

Krieter, P., Chiang, N., Gyaw, S., Skolnick, P., Crystal, R., Keegan, F., Aker, J., Beck, M., & Harris, J. (2016). Pharmacokinetic properties and human use characteristics of an FDA-approved intranasal naloxone product for the treatment of opioid overdose. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 56(10), 1243-1256. https://www.doi.org/10.1002/jcph.759

Manchikanti, L., Kaye, A. M., Knezevic, N. M., McAnally, H., Slavin, K., Trescot, A. M., & Hirsch, J. A. (2017). Responsible, safe, and effective prescription of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Physician, 20(2S), 3-92.

McDonald, J. V. (2015). What do you do, when a patient violates a pain agreement? http://health.ri.gov/publications/guidelines/provider/PatientViolatesPainAgreement.pdf

National Consensus Project. (2018). Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care (4TH ed.). https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Sample patient agreement forms. Retrieved February 1, 2020 from https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/SamplePatientAgreementForms.pdf

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2018a). Misuse of prescription drugs. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/misuse-prescription-drugs/overview

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2018b). Drugs, brains, and behavior: The science of addiction. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/drug-misuse-addiction#footnote

Pain Assessment and Management Initiative. (2019). Pain management & dosing guide. https://com-jax-emergency-pami.sites.medinfo.ufl.edu/wordpress/files/2019/06/PAMI-Dosing-Guide-July-2019.pdf

Qaseem, A., Wilt, T. J., Mclean, R. M., & Forciea, M. A. (2017). Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American college of physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine,166(7), 514-530. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-2367

Schiller, E. Y., & Mechanic, O. J. (2019). Opioid overdose. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29262202

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018a). Buprenorphine. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/treatment/buprenorphine

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018b). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHFFR2017/NSDUHFFR2017.htm

Terrery, C. L., & Nicoteri, J. A. (2016). The 2015 American geriatric society beers criteria: Implications for nurse practitioners. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners,12(3), 192-200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.11.027

Theriot, J., & Azadfard, M. (2019). Opioid antagonists. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537079/

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). HHS acting secretary declares public health emergency to address national opioid crisis. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/10/26/hhs-acting-secretary-declares-public-health-emergency-address-national-opioid-crisis.html

US Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). Pain management best practices inter-agency task force report: Updates, gaps, inconsistencies, and recommendations. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf

US Food & Drug Administration. (2018a). Drug safety and availability – Medication guides. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm085729.htm

US Food & Drug Administration. (2018b). FDA opioids action plan. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/information-drug-class/fda-opioids-action-plan

Webster, L. R. (2017). Risk factors for opioid-use disorder and overdose. Anesthesia Analgesia, 125(5), 1741-1748. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE. 0000000000002496