About this course:

The purpose of this module is to educate healthcare professionals on the key features of suicide as a means to facilitate the early recognition of individuals at risk and to respond with timely, evidence-based interventions to enhance suicide prevention.

Course preview

Notice for nurses licensed in Washington state: This course is not currently approved by the Washington Department of Health, with an application pending. If you would like a notification when this course is approved please email support@nursingce.com

The purpose of this module is to educate healthcare professionals on the key features of suicide as a means to facilitate the early recognition of individuals at risk and to respond with timely, evidence-based interventions to enhance suicide prevention.

Following the completion of this module, the learner should be able to:

- define terms relevant to suicidal behaviors and describe the statistical prevalence of suicide and suicide attempts

- outline the risk and protective factors contributing to suicide, identify warning signs of those at risk for suicide, and the most common means

- discuss the components of a suicide risk assessment, determine the level of risk, and identify evidence-based tools and interventions corresponding to each risk level

- identify indications for urgent and immediate action for a suicide crisis and recognize when to refer a patient for specialized treatment

- describe the components of suicide prevention, lethal means of removal, and safety planning

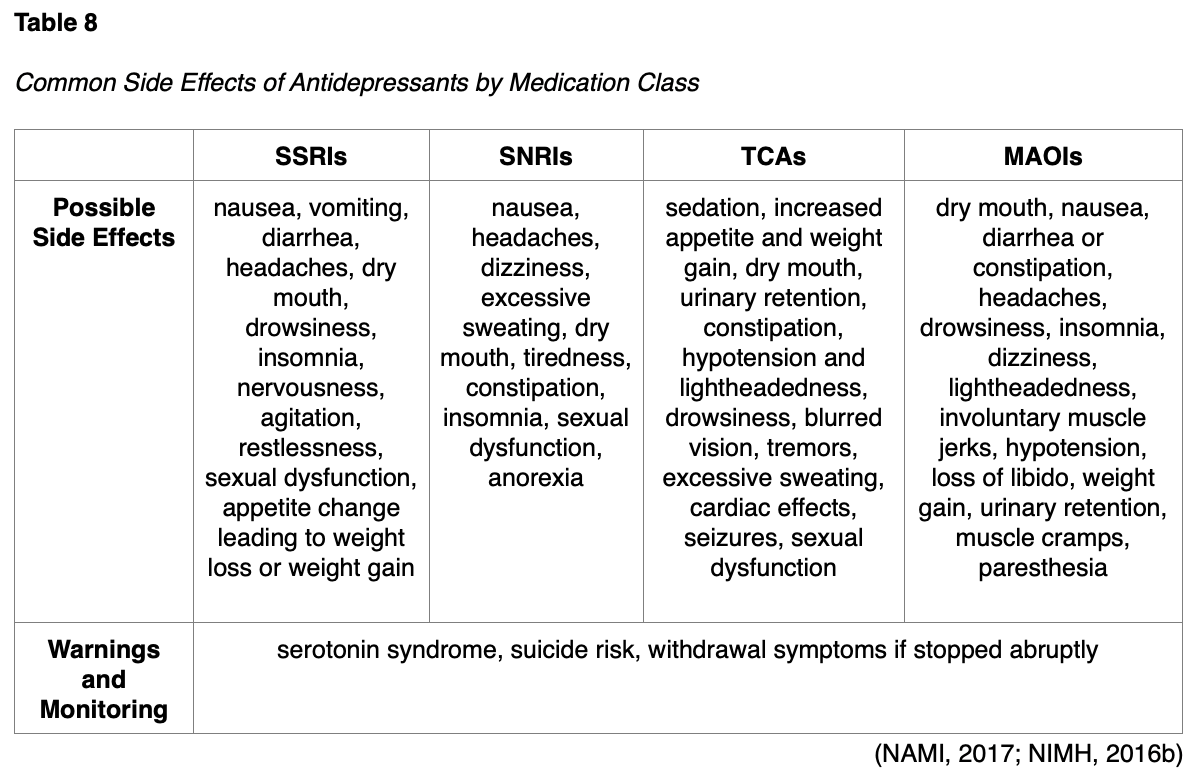

- review evidence-based nonpharmacologic interventions for suicide and depression and outline the pharmacologic treatments, common side effects, and clinical considerations of medication use

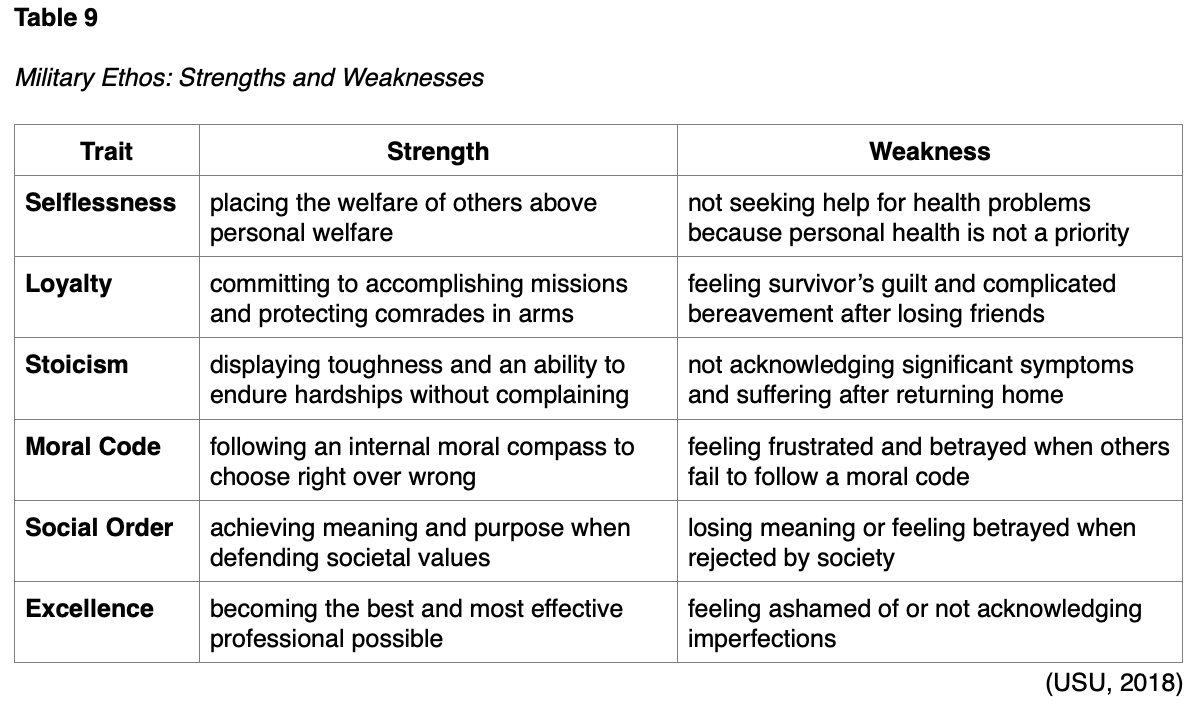

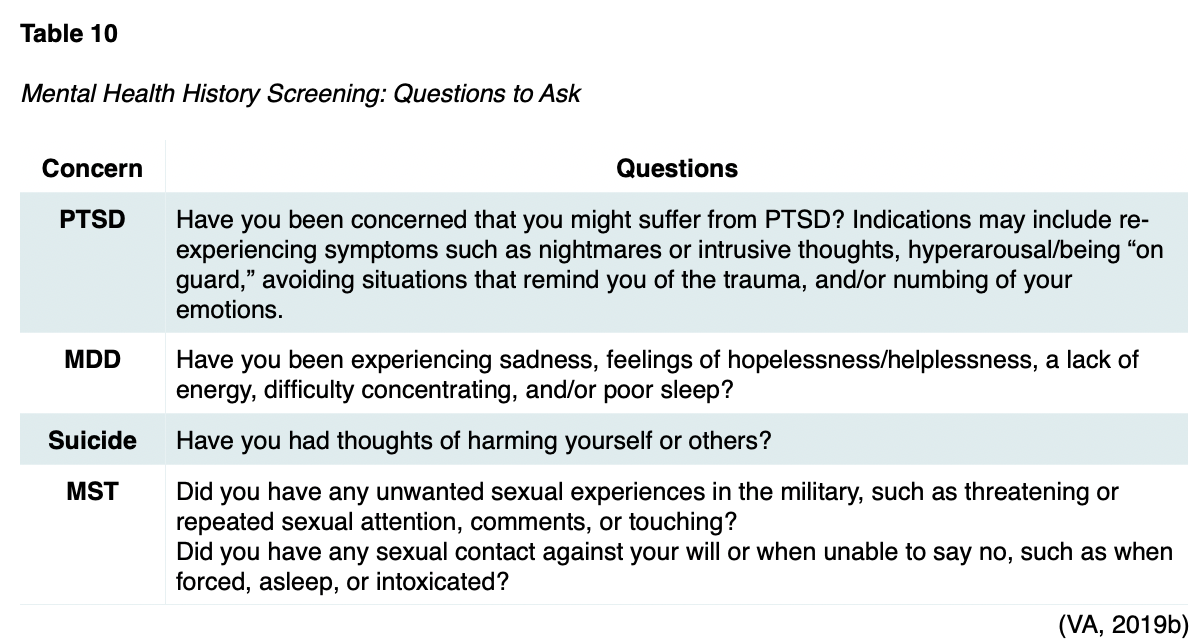

- discuss special considerations regarding suicide and mental health conditions in the veteran population, including key risk assessments, warning signs, and associated management options

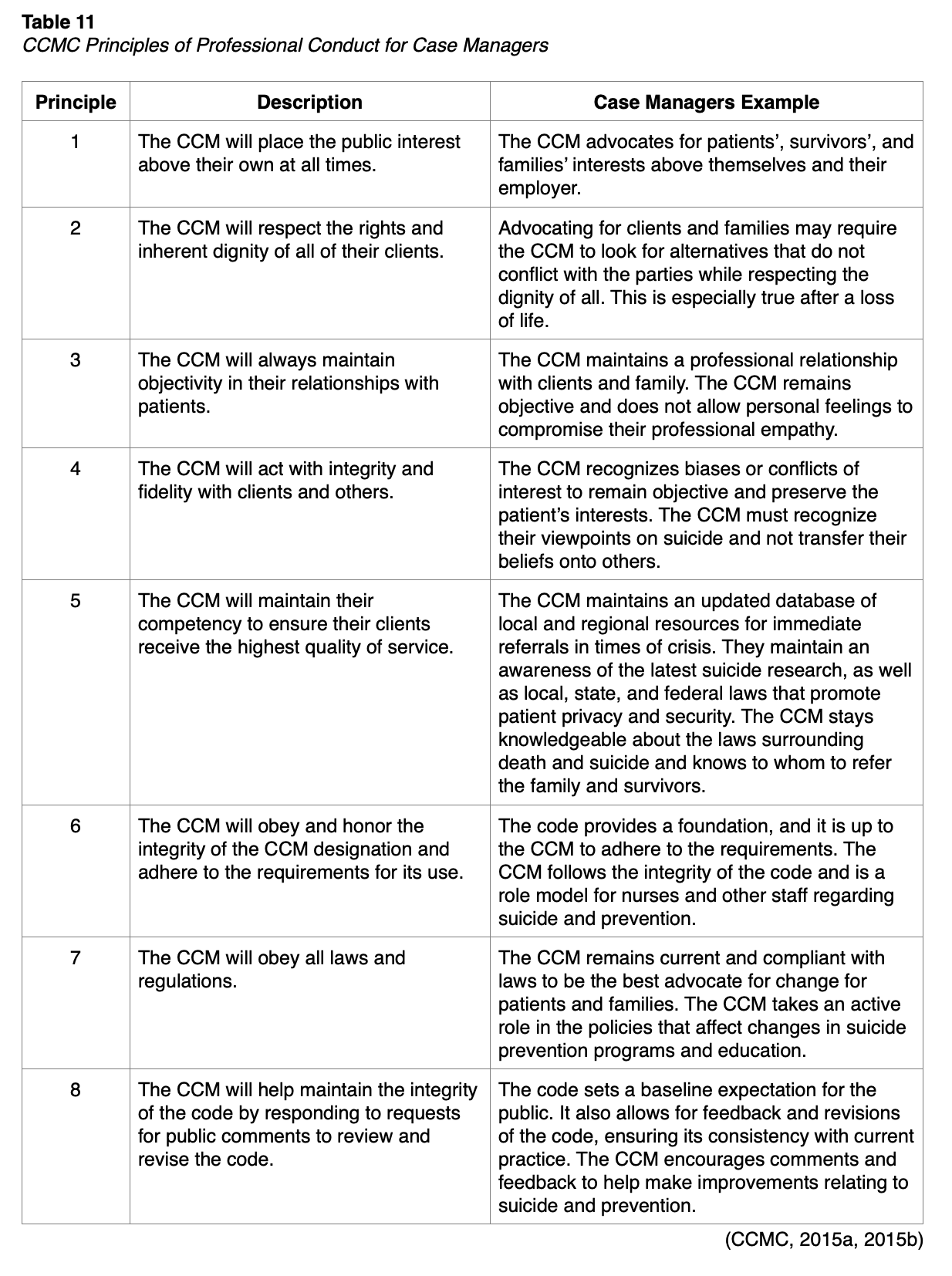

- review the risk of imminent harm through self-injurious behaviors and ethical principles of professional code of conduct for case managers

- identify available resources for adults, teens, and veterans diagnosed with mental illness and their family members

Key Terms

- Suicide: death caused by self-directed injurious behavior and the intent to die due to the behavior

- Suicidal behavior: a term encompassing suicide attempts and suicidal ideation

- Suicide attempt: a non-fatal, self-directed, potentially injurious act intended to result in death that may or may not result in injury

- Suicidal ideation: thoughts about killing oneself that may include a specific plan

- Suicide threat: verbalizing intent of self-injurious behavior intended to lead others to believe that one wants to die, despite no intention of dying

- Suicide gesture: self-injurious behaviors intended to lead others to believe that one wants to die, despite no intention of dying

- Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI): self-injurious behavior characterized by the deliberate destruction of body tissue in the absence of any intent to die and for reasons that are not socially sanctioned

- Suicide means: an instrument or object used to carry out a self-destructive act, such as weapons, chemicals, medications, or illicit drugs

- Suicide methods: actions or techniques that result in an individual inflicting self-directed harmful behavior, such as an overdose (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2021; National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2021; Schreiber & Culpepper, 2021)

Suicide is a complex, multifactorial phenomenon involving various risk factors and warning signs. It is a preventative public health problem with devastating psychological impacts on loved ones and the community. While statistical data regarding suicide and suicide attempts vary based on race, gender, age, and other characteristics, suicide can occur among all demographic groups. All healthcare professionals must understand the defining features, risk factors, and warning signs for suicidal behaviors and the critical components of performing a suicide risk assessment. To combat this growing public health problem, the use of timely, evidence-based interventions must become the standard of care across all healthcare settings (CDC, 2021; Clayton, 2019; National Alliance on Mental Illness [NAMI], 2020).

Suicide Myths and Realities

Various assumptions persist about suicide and suicidal behaviors, including among healthcare professionals (NAMI, 2020; US Department of Veterans Affairs [VA], 2020).

Myth: Asking about suicide will plant the idea in a person’s mind.

Reality: Asking about suicide does not create suicidal thoughts. Asking simply gives the patient permission to talk about their thoughts or feelings.

Myth: There are talkers, and there are doers.

Reality: Most people who die by suicide have previously communicated some intent. Someone who talks about suicide allows the clinician to intervene before suicidal behaviors occur.

Myth: If somebody wants to die by suicide, there is nothing anyone can do about it.

Reality: Most suicidal ideations are associated with treatable disorders. Helping someone find a safe environment for treatment can save their life. The acute risk for suicide is often time-limited. If someone helps the person survive the immediate crisis and overcome their strong intent to die by suicide, a positive outcome is much more likely.

Myth: This individual really wouldn't commit suicide because they…

…just made plans for a vacation.

…have young children at home.

…made a verbal or written promise.

…know how dearly their family loves them.

Reality: The intent to die can override rational thinking. Someone experiencing suicidal ideation or intent must be taken seriously and referred to a clinical provider who can further evaluate their condition and provide appropriate treatment.

Statistics

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the US and is the 2nd leading cause of death among those aged 10 to 24 years. More years of potential life are lost to suicide than to nearly any other cause, except for heart disease, cancer, or unintentional injury. Suicide rates have increased by 33% between 1999 and 2019. In 2019, more than 47,500 people in the US died from suicide. On average, 132 people die by suicide each day, and one person dies every 11.1 minutes (one male every 14.1 minutes and one female every 51.3 minutes). There are 3.6 male deaths by suicide for every female death (CDC, 2019, 2021). According to the American Association of Suicidology (AAS, 2020), White males have the highest suicide rates (26.1 per 100,000), followed by Native Americans/Alaska Natives (13.8 per 100,000), non-White males (12.2 per 100,000), and Black males (11.8 per 100,000). Among females, White females have the highest rate of suicide (7.0 per 100,000), followed by non-White females (3.4 per 100,000) and Black females (2.8 per 100,000). Suicide rates are highest amongst middle-aged adults (45 to 64 years, 19.5 per 100,000), followed by older adults (≥ 65 years, 17.0 per 100,000), and young adults (15 to 24 years, 13.9 per 100,000) in the US (AAS, 2020; NIMH, 2021).

Among adolescents aged 15 to 19, suicide rates have increased by 32% since 2016, rising from 8.4 to 11.1 (per 100,000) deaths. Native Americans/Alaska Natives are the most prominently affected adolescent subgroup (31.6 per 100,000 deaths). Adolescent males are affected at a rate that is over 3 times higher than among females (16.7

...purchase below to continue the course

Researchers also cite differences in suicide means and methods. Among veterans, the latest data demonstrate that firearms account for 50.4% of all suicide deaths and are the most common means of death by suicide among individuals with and without mental health conditions. For veterans in 2017, firearms were the method in 70.7% of male suicide deaths and 43.2% of female suicide deaths (VA, 2019a). Several studies have demonstrated that suicide rates are higher in states with higher gun ownership and that these heightened rates are driven by increases in firearm suicides (American Public Health Association, 2018). Given this finding, it is not surprising that western US states with the fewest firearm laws comprise the top 5 highest suicide rates: Wyoming (29.4 per 100,000), Alaska (28.7 per 100,000), Montana (27.0 per 100,000), New Mexico (24.5 per 100,000), and Colorado (22.8 per 100,000). Following firearms, the most common methods of suicide include suffocation (28.5%) and poisoning (12.9%). While men are more likely to attempt suicide with more lethal methods, such as firearms or suffocation, women are more likely to use poisoning. Those with substance use disorders (SUDs) are 6 times more likely to die by suicide than those without these disorders. Rates of suicide among males with SUD are nearly triple that of those without alcohol or drug problems. Females with SUD have 6-9 times the risk of suicide than females without this factor. Furthermore, research demonstrates that each completed suicide intimately affects at least 6 other people. For a suicide every 11.1 minutes, there are more than 6 new loss survivors every 11.1 minutes. Suicide is also accompanied by a tremendous economic burden to society, costing more than $70 billion annually (AAS, 2020; CDC, 2021; Mental Health America [MHA], 2019b).

Self-injurious behavior accompanied by any intent to die is classified as a suicide attempt, which cautions healthcare professionals and society to err deliberately on the side of caution by viewing debatable behaviors as suicidal. While males are more likely to die by suicide, females are 3 times more likely to attempt suicide. Still, it is challenging to determine the exact number of attempted suicides in the US since there is a lack of all-inclusive databases or tracking mechanisms. Data are primarily compiled through self-reported surveys and ICD-10-CM billing codes. Due to the high stigma associated with suicide attempts, they are greatly underreported. According to SAMHSA (2020b), 12.0 million Americans aged 18 or older reported having serious thoughts of suicide, 3.5 million made suicide plans, and 1.4 million attempted suicide. These numbers translate to a suicide attempt every 23 seconds and 25 attempts for every death by suicide across the nation (100-200:1 for young adults and 4:1 for older adults). People who survive a suicide attempt may experience serious injuries that can have long-term health consequences. Many survivors experience high levels of psychological distress for lengthy periods after the initial exposure (AAS, 2020; CDC, 2021).

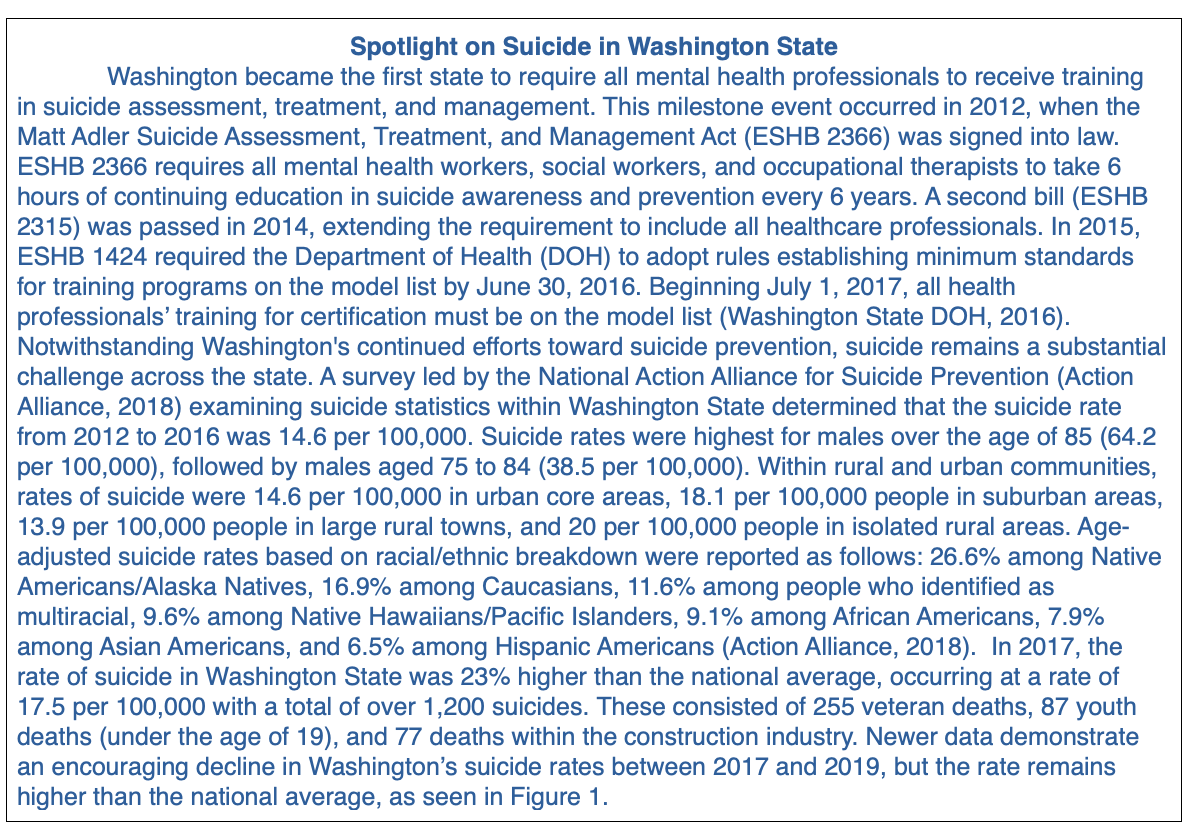

Figure 1

Suicide Rate (per 100,000): Washington vs. United States

(University of Washington Forefront Suicide Prevention, 2021).

Risk Factors

Healthcare professionals must develop a keen awareness and understanding of the risk factors associated with suicide to identify individuals at risk. Assessing suicide risk in primary care offices, emergency departments, outpatient clinics, and other healthcare settings is essential to making appropriate care decisions regarding patients at risk. Healthcare professionals must also acquire the skills necessary to evaluate if an individual is in distress, depressed, in a crisis, or at imminent risk for suicide prompting timely intervention. Risk factors include behavioral signs and symptoms that are statistically related to an individual's amplified risk for suicide. These factors may also include issues related to a person’s background, history, environment, and/or circumstances that increase their risk potential or likelihood of suicidal behavior. Individuals differ in the degree to which risk factors affect their propensity for engaging in suicidal behaviors, and the weight and impact of each risk factor will vary by person and throughout their lifespan (The Joint Commission [TJC], 2019; Suicide Awareness Voices of Education [SAVE], 2019).

While a combination of situations and factors contribute to suicide risk, a prior suicide attempt is the strongest single factor that predicts future risk. The risk for dying by suicide is more than 100 times greater during the first year following an initial (index) suicide attempt (Jason Foundation [JF], 2021). Studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between people who re-attempt suicide, those who complete it, and the timing of the re-attempt (Schreiber & Culpepper, 2021). In a prospective study evaluating 371 adult patients with a suicide attempt, 19% (70 people) re-attempted, and 60% of re-attempts occurred within the first 6 months (Irigoyen et al., 2019). In an observational study by Parra-Uribe and colleagues (2017), 1,241 first-time suicide attempters were followed over 5 years. Findings concluded that most (88%) suicide re-attempts and completed suicides (93%) took place within the first 2 years. Olfson and colleagues (2017) determined that suicide risk was 37% higher in the first year after deliberate self-harm than in the general population. Results from a 32-year follow-up study of 1,044 patients recently published by Probert-Lindstrom and colleagues (2020) revealed that the risk of suicide following a suicide attempt persists for up to 32 years after the initial attempt. At the 32-year follow-up point, 37.6% of participants had died—7.2% by suicide—and 53% of these happened within the first 5 years following the suicide attempt (Probert-Lindstrom et al., 2020).

While risk factors increase the likelihood of suicide, they are not always direct causes. Even among those who have risk factors for suicide, most people do not attempt suicide. While it remains difficult to predict who will act on suicidal thoughts, the risk for suicide rises as the current number of contributing risk factors increases. Other than a prior suicide attempt, the most well-cited risk factors for suicide include the following:

- General Risk Factors:

- social isolation or alienation

- recent or ongoing impulsive and aggressive tendencies and/or acts

- problems tied to sexual identity and relationships

- problems linked to other personal relationships

- Environmental Influences:

- low socioeconomic status

- access to lethal means, including firearms and drugs

- barriers to accessing health care and treatment

- prolonged stress, such as harassment, bullying, relationship problems, or unemployment

- stressful life events like rejection, divorce, financial crisis, other life transitions, or loss

- exposure to another person's suicide or graphic or sensationalized accounts of suicide

- Health Factors:

- mental health conditions, such as:

- SUD/substance abuse problems

- bipolar disorder

- schizophrenia

- hallucinations and delusions

- personality traits of aggression, mood changes, and poor relationships

- conduct disorder

- depression

- anxiety disorders

- persons aged 18 to 25 years prescribed an antidepressant

- persons institutionalized for a mental health condition

- serious physical health conditions, including pain

- traumatic brain injury (TBI)

- mental health conditions, such as:

- Historical Risk Factors:

- previous self-destructive behavior

- history of mood disorder(s)

- history of alcohol and/or other forms of substance abuse

- family history of suicide and/or psychiatric disorder(s)

- loss of a parent or loved one through any means

- history of trauma, abuse, violence, or neglect

- certain cultural or religious beliefs tied to suicide (American Foundation for Suicide Prevention [AFSP], 2021; SAVE, 2019; CDC, 2021)

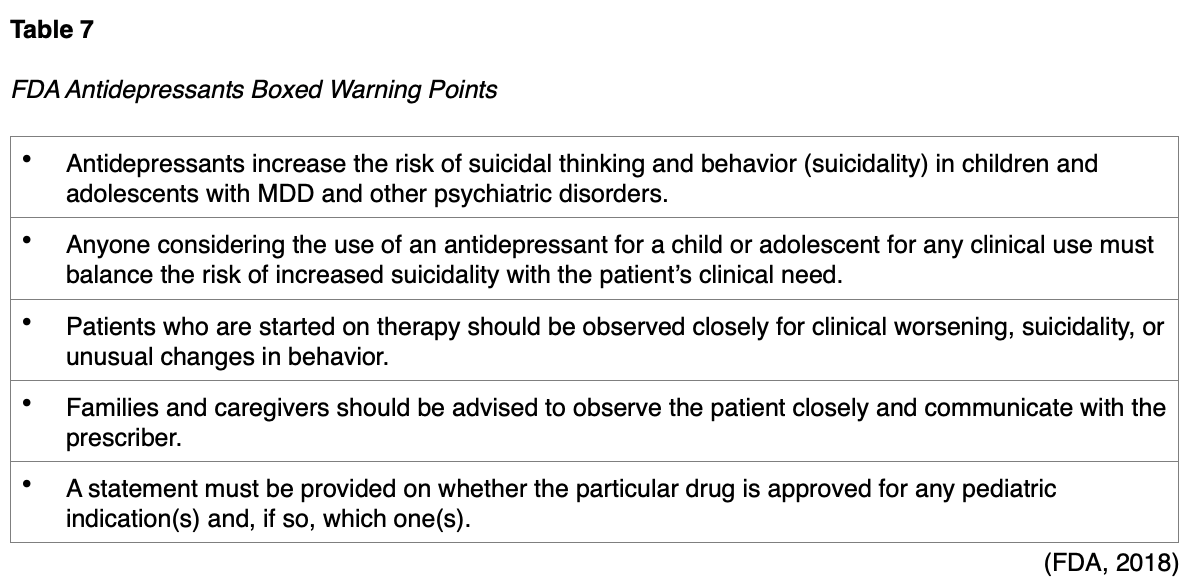

Special populations with an increased risk for suicide include lesbian, gay, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) individuals; military personnel; and incarcerated individuals. Modifiable risk factors, such as mental health conditions, should be managed appropriately to lower a patient’s risk (AFSP, 2021; SAVE, 2019). Suicide among adolescents is most prominently associated with underlying psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder, and SUD. Any combination of psychiatric disorders further heightens the risk for suicide in adolescents. Additional adolescent risk factors include the loss of a parent to death or divorce, physical and/or sexual abuse, a lack of a support network, low self-esteem, feelings of social isolation, and bullying. The stigma associated with asking for help is heightened among adolescents, exacerbating feelings of hopelessness and helplessness and driving intentional self-harm behaviors (JF, 2021; United Health Foundation, 2021).

Protective Factors

Protective factors are key behaviors, environments, and relationships that may enhance resilience and decrease the risk that an individual will attempt suicide. Protective factors have been shown to safeguard individuals from suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Individuals differ in the degree to which protective factors affect their propensity for engaging in suicidal behaviors. Similar to risk factors, each protective factor’s impact on suicidality varies across the lifespan. Research demonstrates some of the most well-established suicide protective factors include the following:

- presence of adequate social support and family connections (connectedness)

- supportive and effective clinical care from medical and mental health professionals

- positive learned skills in coping, problem-solving, conflict resolution, and other nonviolent ways of handling disputes

- cultural and religious beliefs that discourage suicide and support instincts for self-preservation (e.g., intentional participation in religious activities and spirituality)

- restricted access to lethal means, also known as protective environments (CDC, 2021; TJC, 2019; SAVE, 2019)

Warning Signs

Although statistical data demonstrate that most people who die by suicide received some form of healthcare services within the year preceding their death, suicidal ideation is rarely detected. Providers must take all warning signs seriously and offer appropriate support quickly (TJC, 2019). Warning signs indicate an imminent threat (i.e., within hours or days) for the acute onset of suicidal behaviors. These are indicators that the individual may be in acute danger and urgently requires help. The more warning signs the individual displays, the greater their risk of suicide and the higher their need for timely assessment and intervention (AFSP, 2021). While a prior suicide attempt is the most predictive risk factor for completed suicide, the following warning signs are correlated with the highest likelihood of the short-term onset of suicidal behaviors:

- threatening, talking, or thinking about hurting or killing oneself

- searching for ways to kill oneself, including seeking access to drugs or other lethal means (e.g., stockpiling or obtaining weapons, strong prescription medications, or items associated with self-harm)

- writing or posting on social media about death, dying, and suicide

- engaging in self-destructive behaviors, such as substance misuse or violence (AFSP, 2021; CDC, 2021; SAVE, 2019)

These circumstances are medical emergencies, as they warrant immediate attention, evaluation, referral, and hospitalization. Any individual who displays these warning signs is considered at a high level of risk for suicide and suicide crises, requiring immediate intervention to ensure their safety (for further details, refer to the section on suicidal crisis management). Additional warning signs and behaviors that require a prompt mental health evaluation and precautions to ensure the safety of the individual include the following:

- expressing feelings of hopelessness and a lack of purpose or reason to live

- talking about feeling trapped or in unbearable pain

- increasing the use of drugs and/or alcohol

- changing behavior regarding eating and sleeping (too little or too much)

- fixating on death and/or violence

- engaging in self-destructive or risky behaviors

- withdrawing or expressing feelings of isolation

- showing extreme or dramatic changes in mood and personality, such as acting anxious, agitated, restless, irritable, or enraged, or talking about seeking revenge

- expressing overwhelming self-blame, remorse, guilt, or shame

- feeling like a burden to others

- giving away prized possessions

- losing interest in things

- experiencing bullying, sexual abuse, or violence

- expressing any of the following statements:

- "I wish I were dead."

- "I'm going to end it all."

- "You’ll be better off without me."

- "What's the point of living?"

- "Soon, you won't have to worry about me."

- "Who cares if I'm dead, anyway?" (AFSP, 2021; SAVE, 2019)

Frequently, warning signs of suicide in adolescents may mimic “typical teenage behaviors,” so parents may not readily identify behavior that raises concern for suicide in this age group. Healthcare professionals must watch for the distinct warning signs among this age group to identify those at risk and educate parents/caregivers on signs to monitor for at home. Prominent warnings in adolescents include signs that persist over time, several signs that appear simultaneously, and behavior changes that are “out of character.” Suicide threats may be direct or indirect statements (e.g., “I hate my life” or “I won’t be bothering you much longer”). Threats are not always verbal, and adolescents may express themselves via text messages or social media accounts (e.g., Twitter or Facebook). A preoccupation or obsession with suicide or death is a well-cited warning sign among adolescents. It can be expressed verbally through writing (e.g., poems or essays) or abstractly (e.g., artwork and drawings). Signs of depression that warrant increased attention include withdrawing from friends, a lack of hygiene, changes in eating and sleeping habits, irritability and aggressiveness, and a decline in school performance. Furthermore, problems with concentration, sudden difficulty staying focused, taking excessive risks (i.e., being reckless), and increased use or abuse of alcohol or drugs should raise clinical suspicion (JF, 2021; United Health Foundation, 2021).

Suicide Risk Assessment

A suicide risk assessment is a process by which a healthcare professional gathers clinical information to determine an individual's risk for suicide. A risk assessment identifies behavioral and psychological characteristics associated with an increased risk for suicide, allowing for the implementation of effective, evidence-based treatments and interventions to reduce this risk. A risk assessment for suicide is an ongoing process, as suicidal behaviors can fluctuate quickly and unpredictably. Screening responsibilities are no longer limited to medical providers, as current health policy and suicide prevention guidelines call for the support and participation of all healthcare professionals, regardless of their work setting (acute or non-acute) or specialty. This includes but is not limited to physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, behavioral health specialists, social workers, and case managers. A complete risk assessment must include the following vital aspects:

- information about past, recent, and present suicidal ideation and behavior

- information about the patient's context and history

- prevention-oriented suicide risk formulation anchored in the patient's life context (Action Alliance, 2019b)

The Action Alliance (2018) published an updated guideline, Recommended Standard Care for People with Suicide Risk, which supports 2 critical goals cited by the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention (US Department of Health & Human Services [HHS], 2021):

• goal 8: promote suicide prevention as a core component of healthcare services

• goal 9: promote and implement effective clinical and professional practices for assessing and treating those identified as being at risk for suicidal behaviors

Together, the Action Alliance (2019b) and National Strategy, which was last updated in 2021, put forth the Zero Suicide (ZS) Model, which provides a framework through which to coordinate a multilevel approach to implementing evidence-based practices. ZS encourages the screening of all patients for suicide risk on their first contact with an organization and at each subsequent encounter. The core elements of the ZS model include ongoing risk assessment, collaborative safety planning, evidence-based interventions specific to the identified risk level, lethal means reduction, and continuity of care. Structuring a suicide risk assessment is not a straightforward task and involves asking difficult questions about suicidal ideation, intent, plan, and prior attempts. Individuals may openly respond to queries and engage in discussion, or they may be limited in their replies and offer minimal information. At times the patient may bring up the topic on their own, but research demonstrates that this is rare (Brodsky et al., 2018; HHS, 2021; SAMSHA, 2017). The list below outlines the assessment of risk for suicide as compiled and adapted from the Action Alliance (2018) and HHS (2021) guidelines:

- The suicide risk assessment should include consideration of risk and protective factors that may increase or decrease the patient's risk of suicide.

- Observation and existence of warning signs and the evaluation of suicidal thoughts, intent, behaviors, and other risk and protective factors should be used to inform any decision about a referral to a higher level of care.

- Mental state and suicidal ideation can fluctuate considerably over time. Any person at risk for suicide should be re-assessed regularly, especially if their circumstances have changed.

- The clinician should observe the patient's behavior during the clinical interview. Disconnectedness or a lack of rapport may indicate an increased risk for suicide.

- The healthcare professional should remain both empathetic and objective. A direct, non-judgmental approach allows the healthcare provider to gather the most reliable information collaboratively and encourages the patient to accept help.

To assess a patient’s suicidal thoughts, the healthcare professional should inquire directly about thoughts of dying by suicide or feelings of engaging in suicide-related behavior. The distinction between NSSI and suicidal behavior is essential. Healthcare professionals should be direct when inquiring about any current or past thoughts of suicide and ask individuals to describe any such thoughts. According to the Action Alliance (2018) and HHS (2021), a comprehensive evaluation of suicidal thoughts should include the following:

- onset (when did it begin)

- duration (acute, chronic, recurrent)

- intensity (fleeting, nagging, intense)

- frequency (rare, intermittent, daily, unabating)

- active or passive nature of the ideation (“wish I was dead” vs. “thinking of killing myself”)

- whether the individual wishes to kill themselves or is thinking about or engaging in potentially dangerous behavior such as cutting to relieve emotional distress

- lethality of the plan (no plan, overdose, hanging, firearm)

- triggering events or stressors (relationship, illness, loss)

- what intensifies the thoughts

- what distracts the thoughts

- association with states of intoxication (if thoughts are triggered only when the individual is intoxicated)

- understanding the consequences of future potential actions (Action Alliance, 2018; HHS, 2021; SAMSHA, 2017)

To assess suicidal intent, the healthcare professional should appraise past or present evidence (implicit or explicit) that the individual wishes to die, means to kill themselves, and understands the probable consequences of their actions or potential actions. This includes the following (Action Alliance, 2018, 2019; HHS, 2021; SAMSHA, 2017):

- Patients should be asked the degree to which they wish to die, mean to kill themselves, and understand the probable consequences of their actions or potential actions.

- The evaluation of intent to die should be characterized by the following:

- strength of the desire to die,

- strength of the determination to act, and

- strength of the impulse to act or the ability to resist the impulse to act.

- These factors may be highlighted by querying how much the individual has thought about a lethal plan, can engage that plan, and is likely to carry out the plan.

To assess for preparatory behavior, the healthcare professional should evaluate if the patient has begun to prepare for engaging in self-directed violence, such as assembling a method or preparing for death. In addition to obtaining collateral information from the patient’s family members, medical records, and therapists, healthcare professionals should assess preparatory behaviors by inquiring about the following:

- mentally walking through the potential attempt

- researching methods on the internet

- thoughts about the location they would consider and the likelihood of being found or interrupted

- seeking access to lethal means or exploring the lethality of means, such as:

- walking to a bridge

- handling a weapon

- acquiring a firearm or ammunition

- hoarding medication

- purchasing a rope or blade

- taking action or other steps in preparing to end one's life, such as:

- writing a will or suicide note

- giving away possessions

- reviewing a life insurance policy (Action Alliance, 2018, 2019b; HHS, 2021; SAMSHA, 2017)

Healthcare professionals should obtain information from the patient and other sources about previous suicide attempts. Historical suicide attempts may or may not have resulted in injury and may have been interrupted by the patient or another person before a fatal injury.

The risk assessment for suicide should include information from the patient and collateral sources about previous suicide attempts and circumstances surrounding the event (e.g., triggering events, the method used, consequences of behavior, the role of substances of abuse) to determine the lethality of any previous attempt. Healthcare professionals should inquire about:

- if the attempt was interrupted by the patient or another person

- whether there was evidence of an effort to isolate or prevent discovery

- if there have been previous and possibly multiple attempts (Action Alliance, 2018, 2019b; SAMSHA, 2017)

For patients who have a history of prior interrupted (by self or another) suicide attempt(s), obtain additional details to determine factors that enabled the patient to resist the impulse (if self-interrupted) and prevent future attempts (Action Alliance, 2018, 2019b; SAMSHA, 2017).

Evidence-Based Risk Assessment Tools for Suicide

A comprehensive suicide risk assessment requires the use of a validated, evidence-based screening tool, which consists of a set of directed questions. Evaluating the risk level and appropriate actions for each risk level is a critical aspect of suicide prevention. Certain responses are necessary according to the different risk and assessment levels. All healthcare professionals must understand how to perform a proper risk assessment, ascertain risk level, and respond according to evidence-based guidelines. Several tools have been developed and are used throughout various clinical settings. Within the same facility or working environment, all staff members are encouraged to use the same tool and procedures to ensure that patients with suicide risk are identified and managed consistently. Similarly, healthcare professionals must become familiar with and comfortable using the assessment tool to elicit open discussion with the patient. The standard of care in suicide risk assessment requires clinicians to conduct a thorough suicide risk assessment when a patient first screens positive (Action Alliance, 2018; Falcone & Timmons-Mitchell, 2018).

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

The C-SSRS is one of the most widely used, validated, and evidence-based instruments in suicide risk assessment and is available in 114 languages. Several versions of the C-SSRS have been developed for clinical practice. The tool is supported by extensive evidence that reinforces the tool’s validity as a screening method for longitudinally predicting future suicidal behaviors. It screens for a wide range of suicide risk factors straightforwardly and concisely, using direct language to elicit honest responses. The C-SSRS provides a framework through which to assess suicide risk and NSSI, identify the risk level, and guide appropriate action according to the risk level. The C-SSRS is endorsed by several major organizations, including the Action Alliance, SAMHSA, CDC, World Health Organization (WHO), and National Institutes of Health (NIH). When using this tool, the healthcare professional asks a series of questions about the patient’s suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Some sample questions include the following (Brodsky et al., 2018; Columbia Lighthouse Project, 2016; HHS, n.d.):

- “Have you wished you were dead or wished you could go to sleep and not wake up?”

- “Have you been thinking about how you might kill yourself?”

- “Have you taken any steps toward making a suicide attempt or preparing to kill yourself, such as giving valuables away, getting a gun, or writing a suicide note?”

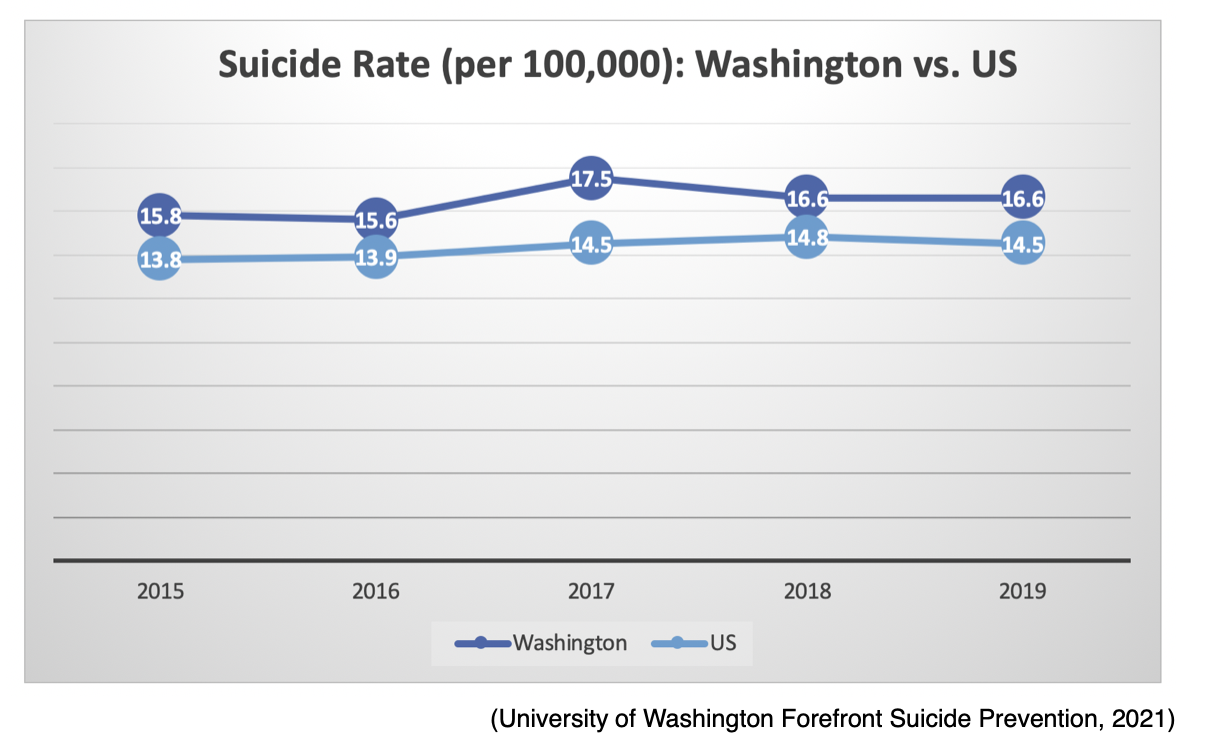

Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage (SAFE-T)

SAFE-T is a tool that incorporates the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guidelines for suicide assessment and is used most commonly in emergency departments by clinicians and nurses. SAFE-T can identify risk and protective factors; inquire about suicidal thoughts, behavior, and intent; and determine the patient’s risk level. It provides appropriate interventions directly to enhance safety. The 5 steps are outlined in Figure 2 (HHS, 2009).

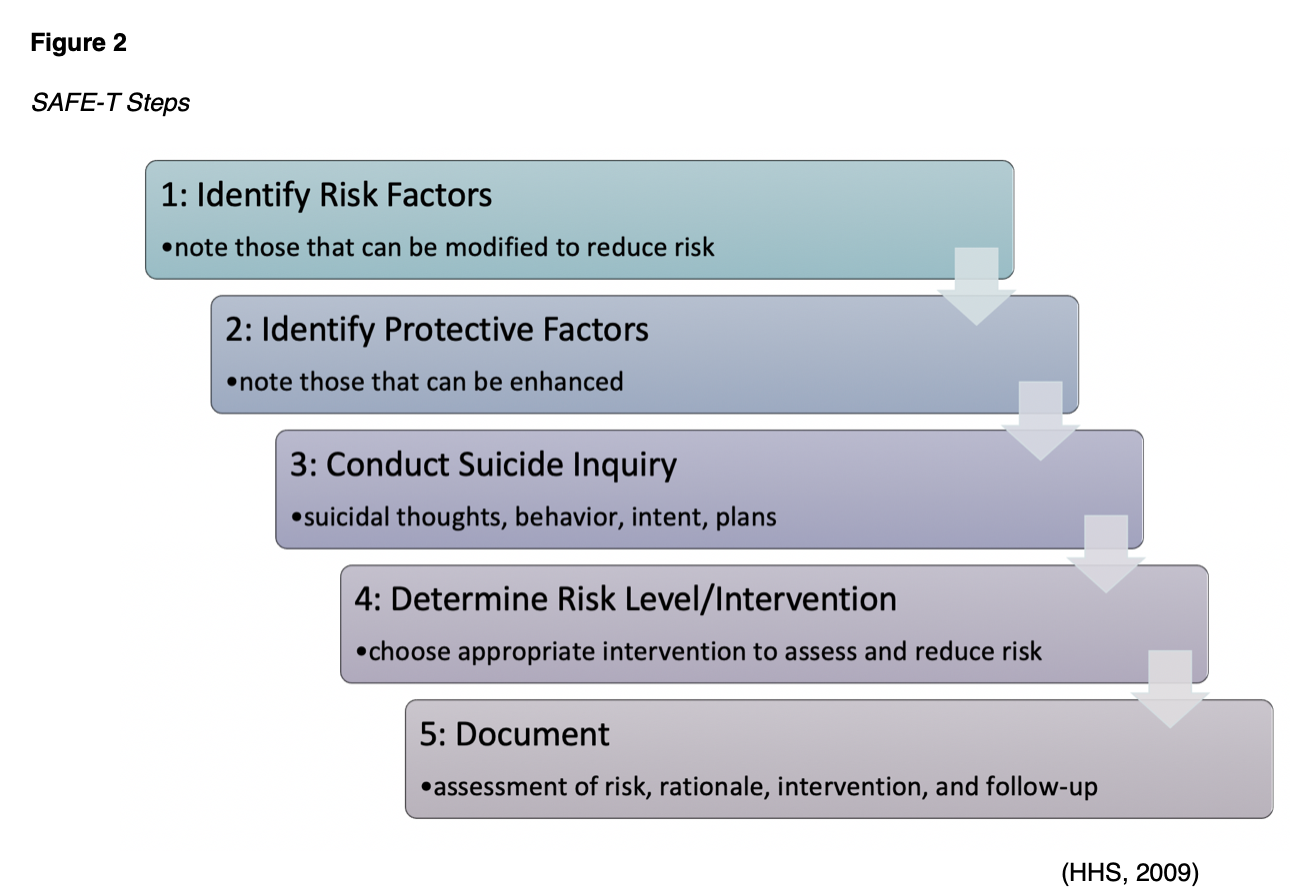

According to the SAFE-T screening tool, a person’s risk of suicide can be any of 3 levels: low, moderate, or high. These risk levels, defining features, and interventions are summarized in Table 1. Suicide precautions should be implemented whenever a patient is deemed at risk. For patients determined to be at low risk of suicide, the healthcare professional should make personal and direct referrals to outpatient behavioral health and other providers for follow-up care within a week of the initial assessment, rather than leaving the patient to make the appointment (Columbia Lighthouse Project, 2016; HHS, 2009).

Suicide Risk Reassessment

Reassessment of a patient’s suicide risk should occur when there is a change in their condition (e.g., relapse of alcoholism) or psychosocial situation (e.g., the end of an intimate relationship) that suggests increased risk. Healthcare professionals should update information about a patient’s risk factors when changes in their symptoms or circumstances indicate increased or decreased risk (Action Alliance, 2018).

Suicide Prevention

Preventing suicide is the primary objective of suicide risk assessment and management. The most effective strategies focus on strengthening suicide protective factors, such as improving access to mental health services, counseling, and other psychosocial resources. Managing mental health conditions (especially depression) is one of the most important interventions for suicide risk reduction and includes both nonpharmacological and pharmaceutical treatments based on individual needs (NIMH, 2019).

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

For those with suicidal ideation, each patient and their family members should be given information to access the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255). Counselors are available via the national toll-free phone number, on a web-based live chat (suicidepreventionlifeline.org), by text, or through a mobile application. This service is available across the US, 24 hours a day and 7 days a week. Furthermore, individuals should also be provided with contact information for local crisis and peer support contacts.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline lists the following 3 "prompt questions" which address current suicidal desire, recent (past 2 months) suicidal desire, and prior suicide attempts:

- Are you thinking of suicide?

- Have you thought about suicide in the last 2 months?

- Have you ever attempted to kill yourself?

An affirmative answer to any or all of these questions requires the crisis telephone worker to conduct a full suicide risk assessment based on subcomponents that review suicidal desire, suicidal capability, suicide intent, and buffers or connectedness. Since isolation is an identified risk factor and a potential precipitant of suicide, engagement of supportive third parties is critical if endorsed by the individual at risk for suicide. Third parties should be aware of the safety plan and understand resources to ensure safety (Action Alliance, 2018; National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, n.d.; SAMHSA, 2017).

Impulsivity and Access to Lethal Means

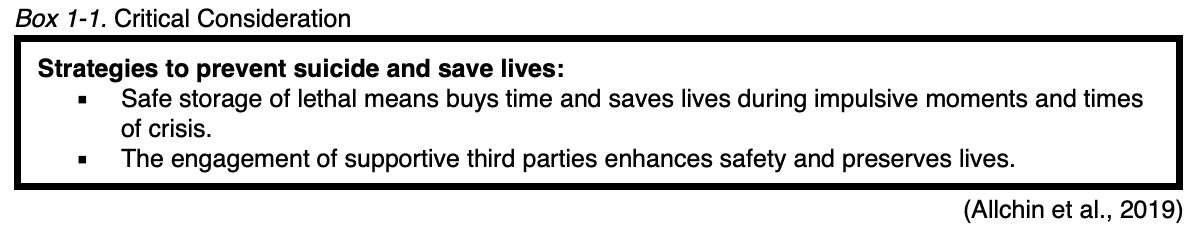

As described earlier, firearms are the most lethal and most common method of suicide in the US, and suicide attempts with a firearm are overwhelmingly fatal. Firearm owners are not more suicidal than non-firearm owners; instead, their suicide attempts are more likely to be fatal. The connection between impulsivity and access to lethal means dramatically enhances the risk of death by suicide (Harvard School of Public Health, n.d.). The majority of suicide attempts involve little planning and occur during a short-term crisis period by individuals who have access to lethal means. Therefore, there is a direct correlation between death by suicide and access to lethal means, such as firearms. If lethal means are made less available to impulsive attempters, and patients substitute less lethal means or temporarily postpone their attempt, the odds that they will survive increase. Studies have demonstrated that when access to a highly lethal suicide method is restricted, the overall suicide rate drops (Allchin et al., 2019). The VA (2019a) states in their suicide prevention plan that a reduction in access to lethal means at the population level should be implemented as a measure of suicide prevention. This may include firearm restrictions, reducing access to poisons and medications commonly associated with overdose, and barriers to jumping from lethal heights. Such restrictions may be accomplished through lethal means safety counseling (LMSC). LMSC consists of a discussion between a healthcare professional and a patient at risk for suicide. Firearm storage suggestions should be based on the patient’s risk level. Recommendations may include storing guns and ammunition separately, using a gunlock or removing the firing pin, storing firearms in a locked cabinet or safe, disassembling firearms, or keeping them at the home of a trusted individual. The Action Alliance (2018) suggests that healthcare professionals arrange and confirm the removal or reduction of any lethal means when feasible before allowing an at-risk patient to be discharged or return home. Family members or caregivers should be involved to help suicide-proof the home (SAMSHA, 2017).

In addition to restricting access to lethal means, expanding options for healthcare professional education and gatekeeper training has a positive impact on reducing suicide rates. Gatekeeper training is more commonly referred to as "recognition and referral training" (RRT), referring to the critical role that individuals without formalized psychosocial training have on suicide prevention. Washington State endorses RRT’s value in their suicide prevention plan, acknowledging its dramatic impact on suicide prevention. RRT helps educate individuals across the community (e.g., teachers, coaches, emergency responders, clergy), equipping them with the skills to identify people who may be at risk of suicide. It offers training on how to respond to these individuals and refer them to support services and treatment. Since most individuals at risk for suicide seek guidance and support from close contacts (i.e., "gatekeepers"), training these individuals on how to respond to mitigate a person’s suicide risk is vital. RRT strives to create an informed support network of people within communities that are equipped to connect suicidal persons with the right resources. Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST) is one of the most effective and well-cited RRT programs (Stone et al., 2017). Gould and colleagues (2013) evaluated ASIST training’s role within the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline network of hotlines for 2 years in a randomized controlled trial. According to data compiled from 1,410 suicidal individuals who utilized the hotline, callers who spoke with ASIST-trained counselors were able to feel less depressed, less suicidal, less overwhelmed, and more hopeful by the conclusion of their call, compared to callers who spoke to non-ASIST trained counselors. Counselors trained in ASIST were also more skilled at keeping callers on the phone longer and establishing a connection with them (Gould et al., 2013).

Suicide Crisis Management

Suicidal patients typically experience strong feelings of abandonment, loneliness, guilt, and hopelessness. Healthcare professionals absolutely must be equipped to handle the stress of a suicide crisis in a calm, structured manner. As with any other emergency, healthcare professionals should remain with the patient at all times. The goal of suicidal crisis management is to mitigate the patient’s acute risk for suicidal behaviors and maintain their safety. Individuals demonstrating warning signs and behaviors that raise suspicion for suicide crisis should be immediately referred for admission to an inpatient facility, as specialty care is urgently needed. If placement is not possible, refer patients to their local emergency department. Suicide precautions and one-on-one monitoring should be employed until the imminent risk declines. Aside from suicide hotlines, suicidal crisis management also includes other programs that provide assessment, crisis stabilization, and referral to an appropriate level of ongoing care (SAVE, 2019).

The following list highlights the priority actions healthcare professionals should take to preserve the life of patients in an acute suicidal crisis (Action Alliance, 2018; NIMH, 2019; Suicide Prevention Resource Center [SPRC], 2020):

- Do not leave the patient alone. Keep patients in a safe environment under one-on-one observation until acceptable access to care is available.

- Arrange immediate access to care through an emergency department, inpatient psychiatric unit, respite center, or crisis center.

- Assess suicidal patients and their visitors for the presence of items or substances that could be used to attempt suicide or harm others.

- Keep suicidal patients away from anchor points for hanging or materials that could be used for self-injury. Lethal means that are readily available in hospitals and have been used in suicides include bell cords, bandages, sheets, restraint belts, plastic bags, elastic tubing, and oxygen tubing.

Treatment and Management of Suicide

Continuity of care is critical for patients with suicide attempts or suicidal ideation. Effective clinical care should include monitoring patients for a suicide attempt after an emergency department visit or hospitalization and providing outreach, mental health follow-up, therapy, and case management. Many guidelines offer elements of evidence-based practice for suicide prevention as devised by several accredited organizations. While each guideline portrays varying degrees of intervention with appropriate evidence, overall differences in the principles guiding suicide risk assessment and its approach are marginal. In 2018, TJC released a special advisory report defining new requirements for the National Patient Safety Goal 15.01.01, which identifies how to manage patients at risk for suicide. According to the report, for patients who screen positively for suicidal behaviors, TJC encourages healthcare professionals to request permission to contact friends, family, or other outpatient treatment providers. If the patient declines to consent, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) permits a clinician to make these contacts without the patient's permission when they believe the patient may be a danger to self or others (TJC, 2018). All individuals should be given information on the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, as well as local crisis and peer-support contacts. Various psychosocial interventions have been beneficial for individuals experiencing suicidal ideation or behaviors. The healthcare team should provide evidence-based clinical approaches to reduce suicidal thoughts and actions to improve outcomes. Suicide-specific therapy approaches include the following:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CBT-SP)

- The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicide (CAMS)

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

- Problem-Solving Therapy (PST)

- Caring Contacts for post-discharge suicide prevention (Action Alliance, 2018; NIMH, 2019; Stone et al., 2017)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CBT-SP)

CBT-SP is a psychosocial intervention that has been shown to reduce suicide risk and prevent re-attempts. CBT-SP uses a risk-reduction, relapse-prevention approach that includes an analysis of the patient's risk factors and stressors (e.g., school or work-related difficulties, relationship problems) leading to and following the suicide attempt to create awareness and insight into behaviors. CBT-SP can also be used to teach individuals new strategies for coping with stressful experiences, such as recognizing thought patterns and identifying alternative actions when thoughts of suicide arise (NIH, 2019). CBT-SP usually occurs in a one-on-one or group format and can vary in duration from several weeks to months, depending on patient needs. CBT-SP can also incorporate family support and communication patterns that focus on strengthening family dynamics and improving problem-solving and communication within the family unit. Furthermore, a treatment that fosters collaborative and integrated care has been shown to engage and motivate patients, increase retention in therapy, and decrease suicide risk (Bryan et al., 2019; Stone et al., 2017).

Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS)

CAMS is a therapeutic approach to suicide-specific assessment and treatment. It offers a flexible approach through which the clinician and patient collectively develop a unique treatment plan. The framework focuses on the patient’s engagement and cooperation in assessing and managing suicidal thoughts and behaviors and the therapist’s understanding of the patient’s suicidal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. CAMS sessions incorporate ongoing patient feedback on which aspects of treatment are working (or not working) to enhance the therapeutic alliance and increase the patient’s motivation to continue therapy (Stone et al., 2017). The duration of the CAMS treatment varies, depending on the patient’s needs. CAMS has demonstrated efficacy across 5 randomized controlled trials between 2011 and 2020, conducted in inpatient and outpatient settings. It has been shown to reduce suicidal ideation quickly in as few as 6 to 8 sessions, reducing overall symptom distress, depression, and hopelessness. CAMS strives to alter suicidal thoughts, increase hope, and improve clinical care retention. TJC and the CDC have identified CAMS as one of the best evidence-based clinical approaches to reduce suicidal thoughts and behaviors (CAMS-care, 2021; Falcone & Timmons-Mitchell, 2018; SPRC, 2017a).

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT)

DBT was initially intended to treat chronically suicidal patients suffering from borderline personality disorder, a mental illness characterized by unstable moods, relationships, self-image, and behavior. Research has demonstrated that DBT serves a beneficial role in all forms of suicide prevention and is also effective in treating other disorders such as SUD, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), attention deficit disorder, bipolar disorder, and eating disorders. DBT is a multi-component therapy centered on treating disorders involving emotional dysregulation. It is most effective for people at high risk for suicide who also struggle with impulsivity. DBT assumes that many of the problems exhibited by patients are caused by skills deficits, particularly impairments with regulating emotions and inadequate or maladaptive coping. It combines elements of CBT, skills training, and mindfulness techniques to help patients learn how to regulate their emotions, hone their interpersonal skills, and cope with stress. DBT includes 4 primary approaches to treatment delivery: individual psychotherapy, group skills training, between-session or "in-the-moment" telephone coaching, and a therapist consultation team. These approaches are implemented with an ongoing effort to maintain a dialectical balance between accepting reality and changing behaviors. To bridge this gap, DBT offers a range of skills training, focusing on building emotional control and healthy coping behaviors to avert maladaptive behaviors during stressful situations, thoughts, and feelings. The therapist helps the patient when their feelings or actions are disruptive or unhealthy and teaches the skills needed to deal better with upsetting situations (NIMH, 2019). The core goals of DBT include the following:

- improve the patient's skills and motivation

- extend the newly formed skills to the environment

- enhance and maintain the patient's motivation to change

- structure the environment to optimize the implementation of the treatment (Falcone & Timmons-Mitchell, 2018; NIMH, 2019; Prada et al., 2018)

Problem-Solving Therapy (PST)

PST is a structured psychological intervention that helps patients focus on developing specific coping skills for problem areas. Through a collaborative relationship with the therapist, patients engage in active problem-solving activities. Patients learn how to identify and prioritize key problem areas and break them into manageable tasks to develop appropriate coping behaviors and solutions. Therapy focuses on empowering patients to learn how to solve problems on their own. PST may range from 4 to 12 sessions, depending on individual needs, and typically involves the following 7 stages:

- selecting and defining the problem

- establishing realistic and achievable goals for problem resolution

- generating alternative solutions

- implementing decision-making guidelines

- evaluating and choosing solutions

- implementing the preferred solutions

- evaluating the outcome (Falcone & Timmons-Mitchell, 2018; SPRC, 2017b; Stone et al., 2017)

Caring Contacts for Post-Discharge Suicide Prevention

Inpatient and outpatient healthcare professionals serve vital yet distinct roles in caring for individuals with suicide risk. Inpatient care offers medically supervised programs in a hospital setting with resources available around the clock. The average length of stay ranges from 48 hours to 10 days. The primary goal of inpatient care is to mitigate the imminent risk of suicide, initiate treatment, stabilize the patient, and prepare for discharge and outpatient continuing care services. Outpatient healthcare professionals serve ongoing roles in providing a vast array of services to help patients move beyond suicide. The goal of outpatient care is to prevent suicide and enhance overall health and wellbeing. The care transition period is challenging for many reasons. The hospital has discharged the patient and is no longer providing ongoing care. Since the outpatient provider has not yet seen the patient, there is a transition period during which no one is providing clinical supervision (Action Alliance, 2019a).

The concept of caring contacts was introduced by psychiatrist Jerome Motto in the 1970s. The intent was to reduce a suicidal person’s perception of isolation and enhance feelings of connectedness. The premise of caring contacts is facilitating long-term communication for the patient with someone who expresses ongoing support and concern about the individual’s wellbeing. The caring contact should be initiated by the concerned individual and place no demands on the recipient (i.e., the patient). Literature results show that even brief support from caring contacts can reduce suicide and suicide attempts during high-risk periods like after hospitalizations or emergency department visits (Columbia Lighthouse Project, 2016; Falcone & Timmons-Mitchell, 2018).

The Action Alliance (2019a) supports the utilization of caring contacts as the standard of care for all individuals with significant suicide risk after acute episodes or when ongoing services are interrupted (e.g., a scheduled visit is missed). Connecting caring contacts with high-risk individuals has demonstrated efficacy in reducing self-harm and preventing suicide. Caring contacts can be implemented by staff in any program that has provided acute care (i.e., emergency department or inpatient programs), outpatient programs that provide ongoing care (during high-risk periods or when an appointment is missed), or crisis centers that can offer follow-up under contract with other services. Various supportive contact methods can be useful (Stone et al., 2017). For example, a randomized controlled trial using text messaging intervention enrolled 658 active-duty soldiers and marines at risk for suicide. Over 12 months, caring contact communications were delivered via text messaging. These interactions were brief and focused only on expressing care, interest, and support. Caring contacts led to a 44% decrease in the odds of reporting any suicidal ideation during the follow-up period and a 48% decrease in the odds of reporting one or more suicide attempts (Comtois et al., 2019).

Safety Planning

Safety planning is a necessary step in suicide prevention. It should be conducted by collaboratively identifying possible coping strategies with the patient and providing resources for reducing risk. A safety plan is not a "no-suicide contract" (or "contract for safety"), as this measure is not recommended by experts in the field of suicide prevention. Safety planning is an intervention that aims to lower the individual's imminent suicide risk following a risk assessment. A trained healthcare professional should perform safety planning in collaboration with the patient. Various versions of safety planning tools are designed for use in specific clinical settings (e.g., emergency departments, acute care settings, outpatient mental health settings) and populations (e.g., adults, veterans). The safety planning intervention (SPI) is the most widely utilized clinical option. It yields a prioritized written list of warning signs, coping strategies, and resources to use during a suicidal crisis as a means to prevent suicide. The objective is to create an individualized strategy for the person to use during periods of distress. The SPI should begin from within the self and build toward seeking help from external resources. While the plan is devised as a step-wise approach, individuals may advance through the plan without completing prior steps. The major components of the SPI include the following:

- identifying warning signs

- utilizing coping strategies

- socializing with others as a distraction from suicidal thoughts

- contacting family or friends to seek help during a suicidal crisis

- contacting mental health professionals, agencies, or organizations for assistance

- restricting or reducing access to means for completing suicide (TJC, 2020; NIMH, 2019; Stanley & Brown, 2012; Stone et al., 2017)

In a large-scale cohort study, Stanley and colleagues (2018) found that the SPI was associated with a reduction in suicidal behavior and increased treatment engagement among suicidal patients following discharge from the emergency department. Safety planning is only one aspect of caring for a suicidal individual and must be used in combination with the risk assessment and evidence-based treatments (see next section). Table 2 outlines the clinical use and application of the SPI.

The healthcare professional should review and reiterate the patient's safety plan at every interaction until they are no longer at risk for suicide. A safety plan should always include a discussion of how to restrict access to lethal means. When assessing patient access to firearms or other lethal means, professionals should inquire about prescription medications and chemicals. Next, they should discuss removing or locking up firearms, other weapons, and medicines during crisis periods (SPRC, 2020).

Documentation

Thorough documentation of each step in the decision-making process and all communication with the individual at risk for suicide, their family members, significant others, and caregivers is critical. Healthcare professionals must review and update the patient’s plan of care and medical records as appropriate. Documentation should include why the patient is at risk for suicide and all care provided with as much detail as possible. Documentation should consist of the safety plan’s content and the patient's reaction to it, discussions, and approaches to lethal means reduction. Healthcare professionals should also document any follow-up actions to be taken for missed appointments (e.g., texts, postcards, and calls from crisis centers). Since documentation has become the primary communication method among providers, healthcare professionals are encouraged to include detailed descriptions in all assessments and progress notes. Additional documentation should consist of the following:

- the date and time the suicide risk assessment was initially completed, as well as any updated assessments

- the screening tool used to perform the suicide risk assessment

- identified risk factors

- the patient’s response to the suicide risk assessment

- a copy of the patient’s safety plan

- any complications, questions, or problems that occurred during the suicide risk assessment and if the treating medical provider was notified

- education provided to the patient and their family regarding the suicide risk assessment, safety planning, response to education, and details regarding any communication barriers (Action Alliance, 2018)

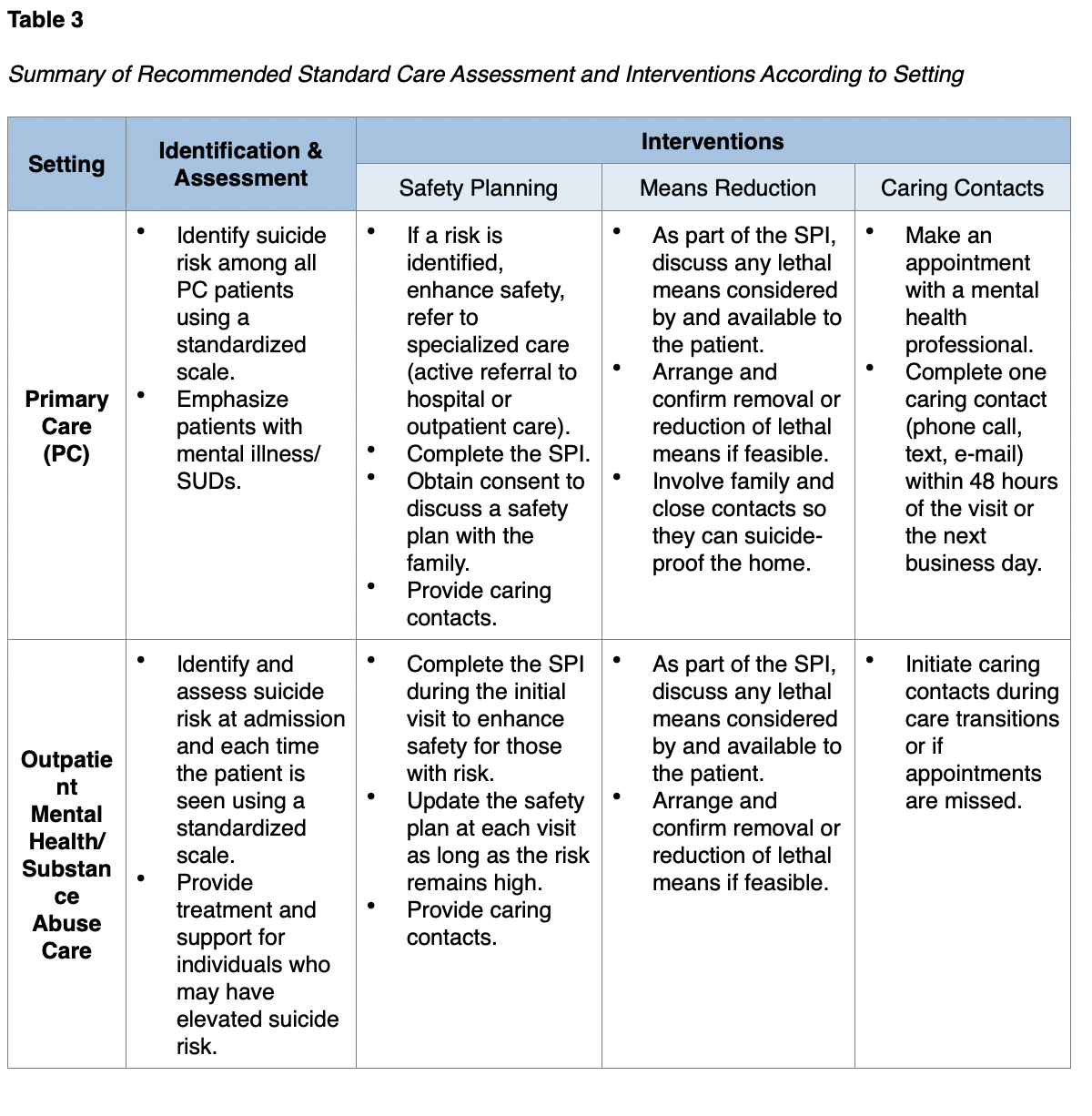

Adapted from the Action Alliance (2018), Table 3 provides an overview of the recommendations for suicide identification, assessment, and accompanying interventions based on the setting.

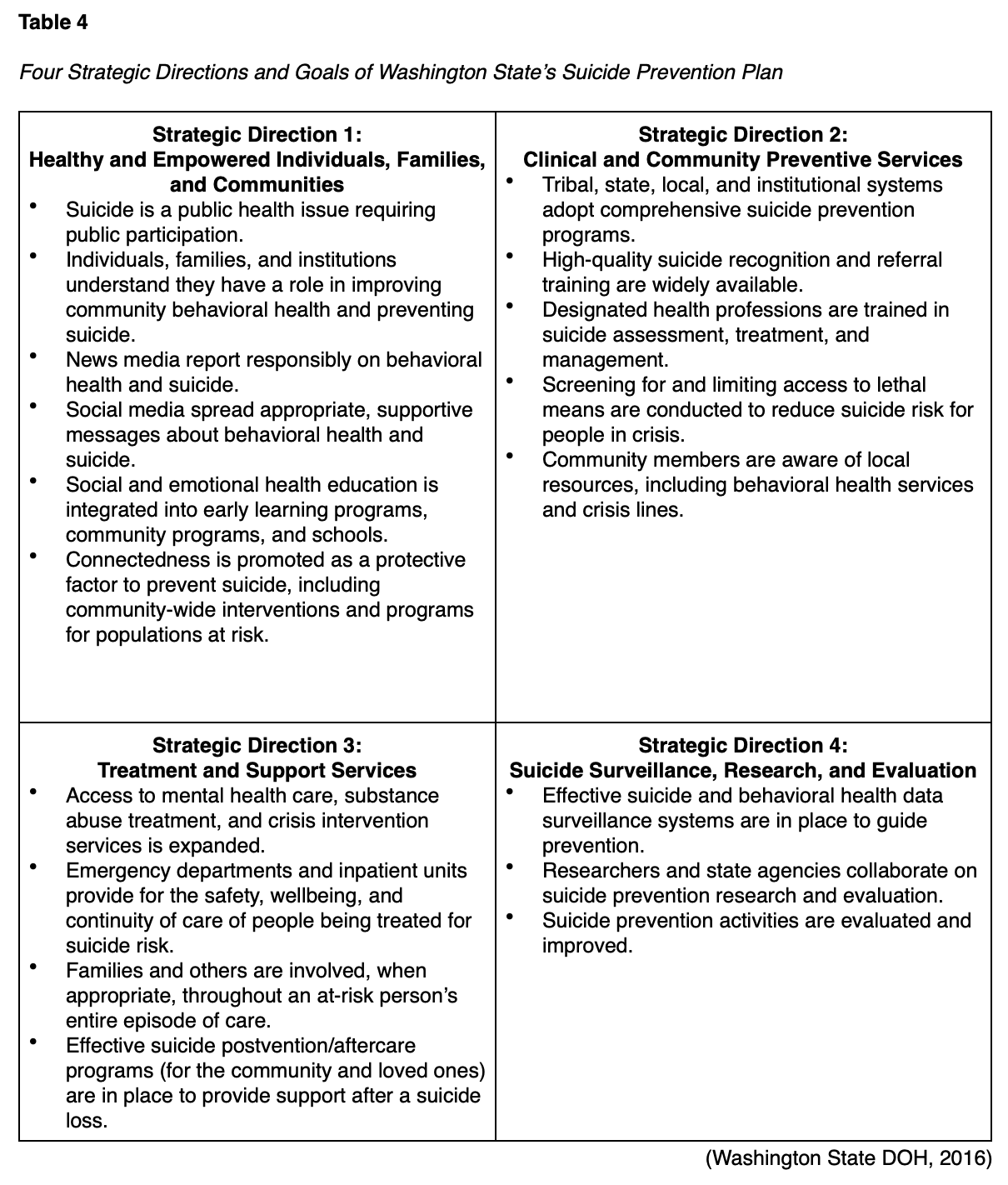

Core Principles of the Washington State Suicide Prevention Plan

Washington State has been a pioneer in suicide prevention and a leader in developing community and policy solutions. Washington has devised a 4-part strategic plan that is directly aligned with the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention. All of the recommendations are consistent with other state and national public health approaches, thereby serving as an exemplary plan. Each component includes relevant and actionable goals and recommendations for policy, system change, and community involvement. The following principles were identified as the core values and attitudes of the state’s Suicide Prevention Plan (Washington State DOH, 2016, p.1):

- "Suicide is a preventable public health problem, not a personal weakness or family failure.

- Everyone in Washington has a role in suicide prevention. Suicide prevention is not the responsibility of the health system alone.

- Many people avoid discussing suicide.

- Silence and stigma about suicide harm individuals, families, and communities.

- To prevent suicide in Washington, we must change the factors we know contribute to suicide risk, such as childhood trauma, isolation in our communities, access to lethal means, and lack of access to appropriate behavioral health care.

- Suicide does not affect all communities equally or in the same way. Suicide prevention programs should be based on the best available research and best practices while reflecting community needs and local cultures.

- People experiencing mental illness, substance use disorders, trauma, loss, and suicidal thinking and behavior deserve dignity, respect, and the right to make decisions about their care."

Table 4 provides a summary of the 4 strategic directions and goals as outlined in the Washington State DOH Suicide Prevention Plan (2016).

Depression

According to the NIMH (2018), MDD—often referred to as depression—is a mental health condition that can cause severe impairment in thinking and daily functioning. Depression is linked to many complications, the most significant of which is suicide. Depression is among the most common mental disorders in the US and a vital topic to discuss in relation to suicide, as most suicides are linked to some form of psychiatric illness or mood disorder. The more severe a patient’s depression is, the greater their risk of suicide becomes. According to the WHO (2019), as many as 300 million people worldwide are affected by depression. In the US, an estimated 17.3 million adults have had at least one MDE, and more than 8% of adult Americans over age 20 reported depression in a given week from 2013 to 2016. In the US and worldwide, females are almost twice as likely to experience depression as males, and the condition is most common in adulthood but can affect individuals across the lifespan. There is a lower prevalence of depression among Asian adults (3.1%) compared to Hispanic adults (8.2%), European American adults (7.9%), and African American adults (9.2%). The prevalence of depression decreases as the family income level increases. Males with family incomes at 400% above the poverty level had the lowest prevalence of depression of all adult groups. Conversely, women with family incomes below the poverty level had the highest prevalence of depression at 19.8% (Brody et al., 2018; WHO, 2019).

While the exact cause of depression is unknown, it likely results from a combination of environmental, genetic, psychological, and biochemical elements. Some of the most common risk factors include a personal or family history of depression, significant life changes, stress, trauma, and certain medications (NIMH, 2018). Different chemicals in the brain can contribute to the symptoms of depression and are the focus of pharmacological treatments. Genetics play a role in depression, and identical twins have a 70% chance of suffering from depression in their life if one twin has an episode. Personal characteristics like low self-esteem, pessimism, or inadequate stress management can further contribute to depression. Environmental factors that can lead to depression include continuous exposure to violence, neglect, poverty, or abuse. A depressive episode significantly interferes with a person's ability to function daily. To be diagnosed with the condition, symptoms must be present for at least 2 weeks (APA, 2020; NIMH, 2018; WHO, 2019). The most common signs and symptoms of a depressive disorder include the following:

- loss of interest or pleasure in hobbies and activities

- a persistently sad, anxious, or “empty” mood

- feeling hopeless or having a pessimistic attitude

- changes in appetite or weight

- sleep disturbances

- irritability, agitation, or restlessness

- fatigue

- moving or talking slowly

- feelings of low self-worth, guilt, or shortcomings

- difficulty concentrating

- suicidal thoughts or intentions (APA, 2013, 2020; NIMH, 2018)

In a national survey of 36,309 US adults, during the lifetime of an individual suffering from MDD, over 46% voiced a desire to die, and over 39% contemplated their suicide. Researchers also found that people with a history of depression are more likely to have a history of SUD as compared to anxiety or personality disorders. Over 57% of the 36,000 individuals diagnosed with MDD had a history of drug, alcohol, or nicotine abuse (Hasin et al., 2018). Although most people who have depression do not die by suicide, having MDD does increase suicide risk compared to people without depression. The risk of death by suicide may, in part, be related to the severity of a person’s depression (APA, 2020; NIMH, 2018).

Depression Screening

Best-practice guidelines recommend initially screening individuals for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2). The PHQ-2 asks the following priority questions (APA, 2013; HHS, 2021; SAMHSA, 2017):

- Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems?

- little interest or pleasure in doing things

- feeling down, depressed, or hopeless

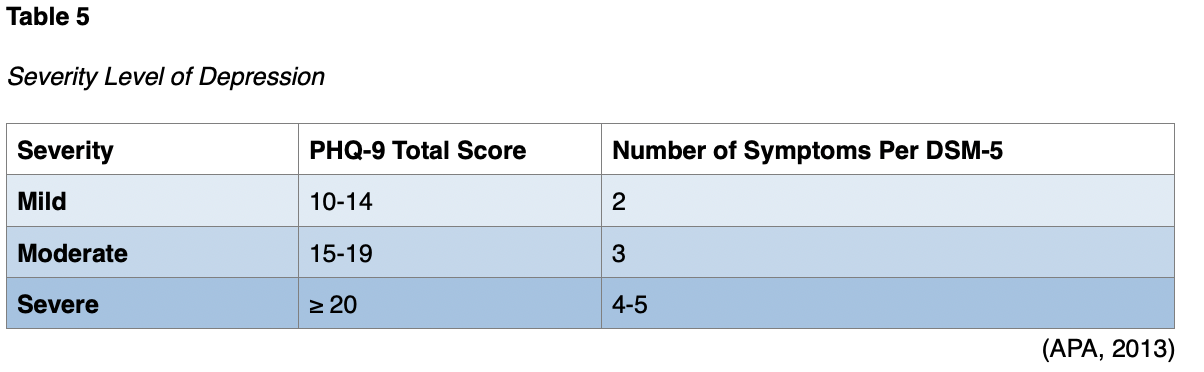

Patients who respond ‘yes’ to either of the questions on the PHQ-2 should undergo additional screening with the PHQ-9—a multipurpose, 9-item symptom checklist used to screen for, diagnose, monitor, and measure the severity of depression. The PHQ-9 incorporates the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th edition (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria for depression and a question that screens for the presence and duration of suicidal ideation (APA, 2013). The tool is brief, easily used in clinical practice, and rapidly scored. It is also useful when monitoring for improving or worsening symptoms. Table 5 demonstrates the scoring categories of the PHQ-9 (Na et al., 2018).

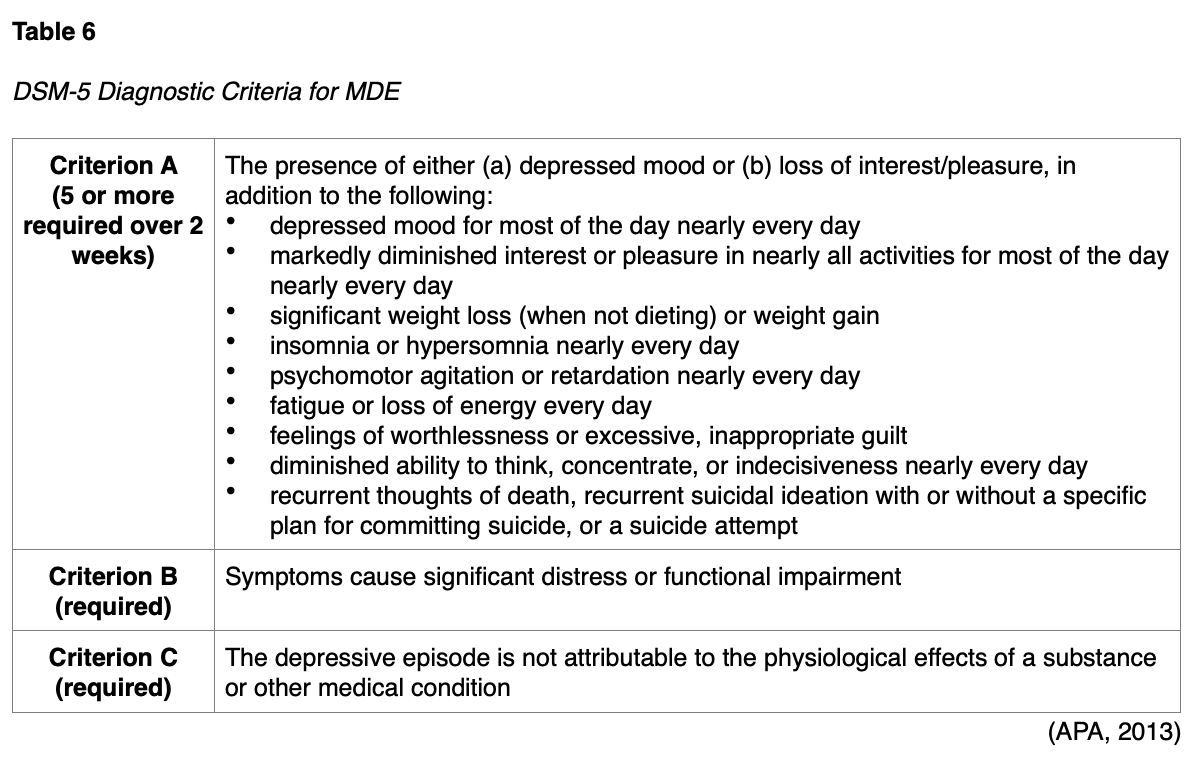

In addition to the PHQ-9, healthcare professionals must evaluate any acute safety risks (e.g., harm to self or others, psychotic features) and assess the patient’s functional status, medical history, past treatment, and family history. While useful and validated for the screening of patients for potential depression, most contend that the PHQ-9 is an insufficient assessment for suicide risk and suicidal ideation compared to other tools, such as the C-SSRS and SAFE-T (Na et al., 2018). Table 6 reviews the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for depression.

Evidence-Based Treatment and Management of Depression

An individualized treatment plan should be developed using shared decision-making and will vary based on the patient’s severity level (mild, moderate, or severe) as outlined below in Table 6. Treatment for depression may include counseling, therapy, and/or antidepressant medication. Adequate treatment can prevent suicide related to depression. The most effective treatment for depression is a combination of psychotherapy with pharmacological treatment, such as antidepressant medication (APA, 2020; NIMH, 2018; VA, 2016).

Non-Pharmacologic Treatments for Depression

Numerous non-pharmacological treatment options may be explored and discussed with patients who wish to avoid medications or desire adjunctive therapy (NIMH, 2018).

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

ACT is an action-oriented intervention in which patients learn to stop avoiding, denying, and struggling with their inner emotions. Instead, they learn to accept these deeper feelings as appropriate responses to specific situations. ACT emphasizes acceptance of emotional distress and engagement in goal-directed behaviors to reduce symptom severity. To facilitate effective behavior change, ACT emphasizes the identification of personal values and helping patients commit to making necessary changes in their behavior (Stein, 2020; Stone et al., 2017).

Behavioral Therapy/Behavioral Activation (BT/BA)

BT refers to a class of psychotherapy interventions that treat depression by teaching patients to increase rewarding activities. Patients track their activities and identify the affective and behavioral consequences. Patients then learn techniques to schedule activities to improve their mood. BT emphasizes training patients to monitor their symptoms and behaviors to identify the relationships between them. BA is a specific technique of BT that targets the link between avoidant behavior and depression to expand the treatment component of BT. BA is essentially a coping strategy that strives to increase behaviors that bring the patient into contact with positive reinforcements and decrease behaviors that impede this contact (Stein, 2020; Stone et al., 2017).

CBT

CBT is a type of psychotherapy reviewed earlier with regard to its benefits in suicide prevention. Strong clinical evidence also supports the use of CBT as an effective treatment for depression. CBT helps patients assess and restructure negative thinking patterns associated with depression. Through CBT, the patient can recognize negative thoughts and learn positive and effective coping strategies. CBT is time-limited and typically consists of 8 to 16 sessions. Patients learn to track their thoughts and activities to identify the affective and behavioral consequences. They subsequently learn techniques to change their way of thinking and activities to improve mood. CBT has demonstrated efficacy across diverse populations, including civilians, veterans, active service members, and family members suffering from depression. CBT can also be administered via computer programs, a process referred to as computer-based CBT (CCBT; Stein, 2020; Stone et al., 2017).

Interpersonal Therapy (IPT)

IPT focuses on improving problems within personal relationships as a core component of depression. While an event or a relationship may not always cause depression, depression affects relationships and can create interpersonal problems. IPT is a short-term treatment that teaches patients to evaluate their interactions to understand and improve how they relate to others. IPT is derived from attachment theory, and it treats depression by focusing on improving interpersonal functioning and exploring relationship-based difficulties. IPT specifically targets 4 primary areas: interpersonal loss, role conflict, role change, and interpersonal skills (IPT Institute, n.d.; Stone et al., 2017).

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)

MBCT integrates CBT interventions with mindfulness-based skills to help patients attend to the present moment in a non-judgmental, accepting manner. Unlike CBT, MBCT does not seek to modify or eliminate dysfunctional thoughts. Instead, it helps patients become more detached and observe their thoughts objectively, without necessarily attempting to change them. MBCT employs meditation, imagery, experiential exercises, and relaxation techniques. Mindfulness is not appropriate as first-line therapy for severe depression but rather as an adjunct or complementary therapy or an alternative for mild symptoms in motivated patients (MacKenzie & Kocovski, 2016).

Brain Stimulation Therapy

Brain stimulation therapies may be considered when other treatments for depression have proven ineffective. Brain stimulation therapy includes electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS; NIMH, 2016a).

ECT. ECT involves transmitting short electrical impulses into the brain. These controlled electric currents provoke a brief period of seizure-like activity. ECT is typically performed in a series of 4-6 treatments before an improvement can be expected, with a total of 6-12 treatments administered over 2-6 weeks; monthly maintenance treatments are sometimes required. The patient is placed under general anesthesia for the treatments and can resume normal activity about an hour following the procedure. ECT can have significant adverse effects, such as headaches, muscle pain, nausea, confusion, and memory loss. It is only utilized in severe depression, depression with psychosis, or bipolar disorder that has not responded to medication and psychotherapy with more conventional methods. In uncomplicated severe depression, ECT has been shown to lead to improved mood in 80% of patients. Patients need to understand both the potential risks and benefits of ECT before beginning treatment (NIMH, 2016a).

TMS. TMS is a relatively new type of brain stimulation that uses a magnet instead of an electrical current to activate the brain. It has not yet been proven effective as maintenance therapy but has been approved by the US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of MDD and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). TMS creates rapidly alternating magnetic fields using a large magnetic coil placed on the patient’s forehead. Patients may need to complete 4-5 sessions of 40 minutes per week over 4-6 weeks to see improvement. TMS is not recommended for patients with psychotic symptoms, bipolar disorder, or a high risk of suicide. TMS is contraindicated in patients with pacemakers or metal objects in their heads. The patient remains alert throughout the treatment, and general anesthesia is not required. TMS must be used with caution in patients with a history of seizures, as it can induce seizure activity. Mild adverse effects include muscle contractions or tingling in the face/jaw, headaches, and lightheadedness (McDonald & Fochtmann, 2019; NIMH, 2016a).

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Complementary and alternative medicine treatments can be used as an adjunct to other evidence-based treatments for depression. When these interventions are combined with evidence-based treatment options, such as prescription medications and psychotherapy, they can contribute to the overall treatment plan for depression. A few pharmacological agents are available over-the-counter for the management of depression, such as hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort), omega-3 fatty acid (fish oil), and s-adenosyl methionine (SAM-e). However, these agents are not FDA-approved for depression. While prescription medications are highly regulated by the FDA to ensure their safety and efficacy, nutritional and dietary supplements are not. The lack of FDA oversight and regulation of these agents poses concerns regarding their consistency, the purity of their ingredients, and safety profiles. Although patients do not require a prescription to obtain these drugs, they still pose a risk for significant adverse effects and dangerous drug interactions. Some complementary and alternative treatments with evidence of positive contributions to the treatment of depression are described below.

Exercise. Exercise increases endorphins and stimulates the secretion of norepinephrine, which can improve a person's mood. According to a recent report by Harvard Health Publishing, the hippocampus in the brain (the region responsible for regulating mood) is smaller in people with depression. Low-intensity exercise that is sustained over time stimulates the release of proteins that cause nerve cells to grow and generate new connections. This improves brain function, supports nerve cell growth in the hippocampus, and improves nerve cell connections. All these processes help to alleviate depressive symptoms (Harvard Health Publishing, 2021).

Yoga. Yoga is a mind and body practice founded in ancient Indian philosophy. It centers on achieving a relaxation response through spirituality and meditation, which is an integral core component of yoga. Meditation is especially beneficial for reducing stress and depressive symptoms. Studies have shown that yoga and meditation have positive benefits for people with depression and various other types of mental health conditions (MHA, 2016; National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health [NCCIH], 2019). Sharma and colleagues (2017) evaluated the feasibility, efficacy, and tolerability of Sudarshan Kriya yoga (SKY) as an adjunctive intervention in patients with MDD. SKY is a breathing-based meditative technique that focuses on slow, medium, or fast rhythmic breathing cycles. It has been reported to decrease cortisol, increase prolactin, and improve antioxidant status in practitioners. Their findings demonstrated that SKY helped alleviate severe depression in people who did not fully respond to antidepressant treatments (Sharma et al., 2017).

Folate levels. Folate, also known as folic acid or vitamin B9, is an essential nutrient present in green leafy vegetables and fortified grain products. Low folate levels have been associated with depression, as well as dementia, in some studies. Further, when folate levels are deficient, patients may not receive the full therapeutic effect from their prescribed antidepressant medication. Studies have shown that adding a folate supplement such as L-methyl folate (Folic acid) can enhance the effectiveness of the antidepressant medication without causing dangerous drug interactions. Further, some studies have demonstrated that L-methyl folate (Folic acid) supplementation may be an effective adjunctive therapy or as a stand-alone treatment in reducing depressive symptoms and improving cognitive function (MHA, 2016; NCCIH, 2019).

Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort). Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort) is a supplement with chemical properties similar to selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and should not be combined with SSRIs. It can expedite or diminishing the metabolism of the prescribed agent, leading to reduced efficacy or higher toxicity. Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort) is notorious for interacting with several additional prescription drugs and can decrease the efficacy of several medications, including:

- HIV medications such as indinavir (Crixivan)

- cancer chemotherapy drugs such as irinotecan (Camptosar)

- cyclosporine (Neoral)

- digoxin (Lanoxin)

- birth control pills

- warfarin (Coumadin; NCCIH, 2019)

L-tryptophan. L-tryptophan is required for serotonin production, which is a primary regulator of mood, behavior, and sleep-wake cycles. Since low serotonin levels are associated with depression and sleep disorders, several studies have linked L-tryptophan supplementation with a reduction in depressive symptoms (Jenkins et al., 2016).