About this course:

The purpose of this activity is to enable the learner to define current standards in wound care and the interdisciplinary team’s role in delivery of wound care and prevention that promotes positive patient outcomes.

Course preview

Interdisciplinary Wound Care: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management

Learning Outcomes

- Recognize the normal anatomy and physiology of the skin.

- Differentiate types of acute and chronic wounds.

- Describe factors that impact the normal healing process.

- Summarize the phases of wound healing.

- Discuss how wounds are diagnosed.

- Explain the nurse’s role in assessing and documenting wounds.

- Identify interventions the nurse uses to prevent acute and chronic wounds.

- Explore treatment options for different categories of wounds and the interdisciplinary role

- Consider legal implications for the care of patients with wounds.

Introduction

Nurses care for wounds in their clinical and community practice of different origins and across the age spectrum. While figures vary across the literature, as much as 20 billion dollars is spent each year on chronic wounds and their care in the United States (Watters, Yuan, & Rumbaugh, 2015). Each patient is unique in risk factors and co-morbidities that may impede the healing process. Wounds may be caused from pressure or tears to the skin, burns, punctures, surgery, bites, scrapes or from venous and arterial insufficiencies. There are many treatment options available to the nurse and the healthcare team to promote healing. The nurse should be aware of current evidence-based treatment modalities including dressings, wound-care products and preventative techniques when caring for patients with acute or chronic wounds. Moreover, the nurse should be knowledgeable about wounds and the treatments available based on individual needs and resources.

We will explore the most common wounds that an interdisciplinary team manages including a review of proper identification and appropriate treatment. It is vital to understand the normal anatomy and physiology of the skin to recognize vulnerability that may lead to wounds. The nurse should be able to identify risk factors, and implement preventative care to avoid wounds, as well as assess for existing wounds to initiate prompt treatment and collaborate with the interdisciplinary team to provide optimal outcomes for the patient with wounds.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Skin

The skin is the largest organ of the body and protects the internal organs and structures from biological invasion, ultraviolet radiation and physical damage. Additional functions of the skin are to provide thermoregulation through sweating and regulation of blood flow, synthesis of Vitamin D, sensation from nerve endings, excretion of salts and small amounts of waste products and provide aesthetics and communication (Peate & Glencross, 2015). There are three layers to the skin: the epidermis, dermis and hypodermis. The health of our skin influences overall health, has a deep psychological significance and identifies the individual with unique facial and body characteristics. Self-image may be enhanced or deterred by society’s standards for one’s appearance (Peate & Glencross, 2015).

The epidermis is comprised primarily of stratified epithelium and sheds dead cells continuously. This layer is slightly acidic with a pH of 4.5-6. The epidermis is made up of five layers, the stratus corneum, stratum lucidum, stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum, and stratum basale. Each layer has its own function and plays a role in the healing process of wounds. The basal layer constantly makes new cells that move up to the surface, flattening during the process and then are shedding after moving to the outer surface. This process takes between 28 and 35 days. Epidermis cells are typically four to five layers deep with more layers present on the soles of the feet and palms of the hands (Peate & Glencross, 2015).

The stratum corneum is tough and waterproof. It is the outermost layer and consists of fibrous dead cells, helping to regulate pH and temperature in addition to providing a protective role. This layer is continuously being replaced and helps with the skin’s ability to repair itself. The stratum lucidum provides extra protection to areas that are exposed to greater deterioration, but is not consistent throughout all areas of the body such as where the skin is thinner. The stratum granulosum is the layer where keratinocytes lose their nuclei and start to flatten and die. Keratinization takes place in this layer and helps reduce loss of water from the epidermis. The stratum spinosum is 8-10 cells thick and contains living cells that have spiny processes called desmosomes. The stratum basale is also known as the basement membrane and is the lowest layer of the epidermis. This layer is one cell thick and forms a border between the epidermis and dermis. Cells are continuously dividing for ongoing rejuvenation of the skin. Melanocytes are produced in this layer as well (Peate & Glencross, 2015).

The primary role of the dermis is to support and provide nutrition to the epidermis. This layer consists mostly of connective tissue or collagen which is tough, fibrous protein that helps skin resist tearing. The dermis has elastic tissue that is resilient and allows the skin to stretch with body movement. The dermis houses the nerves, sensory receptors, blood vessels and lymphatics. The hair follicles, sebaceous glands and sweat glands are embedded in the dermis (Jarvis, 2016).

The hypodermis is the superficial fascia that connects to the skin yet allows it to move. This layer is made up of blood vessels, adipose tissue, and connective tissue that support the dermis. Fat is also stored in this layer to provide internal structures with additional protection as well as insulation against cold (Jarvis, 2016).

Types of Skin Injuries/Wounds

- Abrasions and scrapes occur when a mechanical force, such as the friction of skin rubbing against a hard surface, scrapes way a partial-thickness area of the skin. These wounds can vary in size and depth and can be complicated by dirt or debris that is imbedded into the wound (Wound Care Made Incredibly Easy, 2016).

- Bites can originate from animal or human but the impact can be equally severe. A bite from a dog, cat or rodent can introduce infectious disease including rabies into the wound. Injury to the tissue can occur secondary to the teeth as well as the force of the bite and movement of the animal as they are clamping down on the tissue. A human bite can introduce bacteria from the human mouth including Staphylococcus aureus and streptococci or even serious diseases including HIV, hepatitis B (HBV), syphilis and tuberculosis. There is some evidence that the human bite can cause necrotizing fasciitis (Bassett, Orsted & Rosenthal, 2019).

- Burns may be caused by thermal extremes, electricity, caustic chemicals or radiation. The amount of damage from burns will be dependent on the source, duration of contact or exposure and location of injury to the patient. Pre-existing conditions can complicate the healing of burns and may increase morbidity and mortality related to burns (Wound Care Made Incredibly Easy, 2016).

- Lacerations are tears into the skin caused by a sharp object such as glass, metal, and wood or blunt trauma that causes a shearing force on the skin. The laceration will have irregular edges and will vary in severity according to the cause, size, depth and location.

- Puncture wounds such as stabbing wounds may involve little tissue on the skin surface but may have greater implications or damage below the skin surface including internal organ damage. Further, the patient is at risk for local infection, sepsis and tetanus a

...purchase below to continue the course

- Type I-linear or flap tear that can be repositioned to cover the wound bed.

- Type II-partial tissue loss that cannot be repositioned to cover the wound bed.

- Type III-total skin flap loss exposing entire wound bed. (Slachta, 2016).

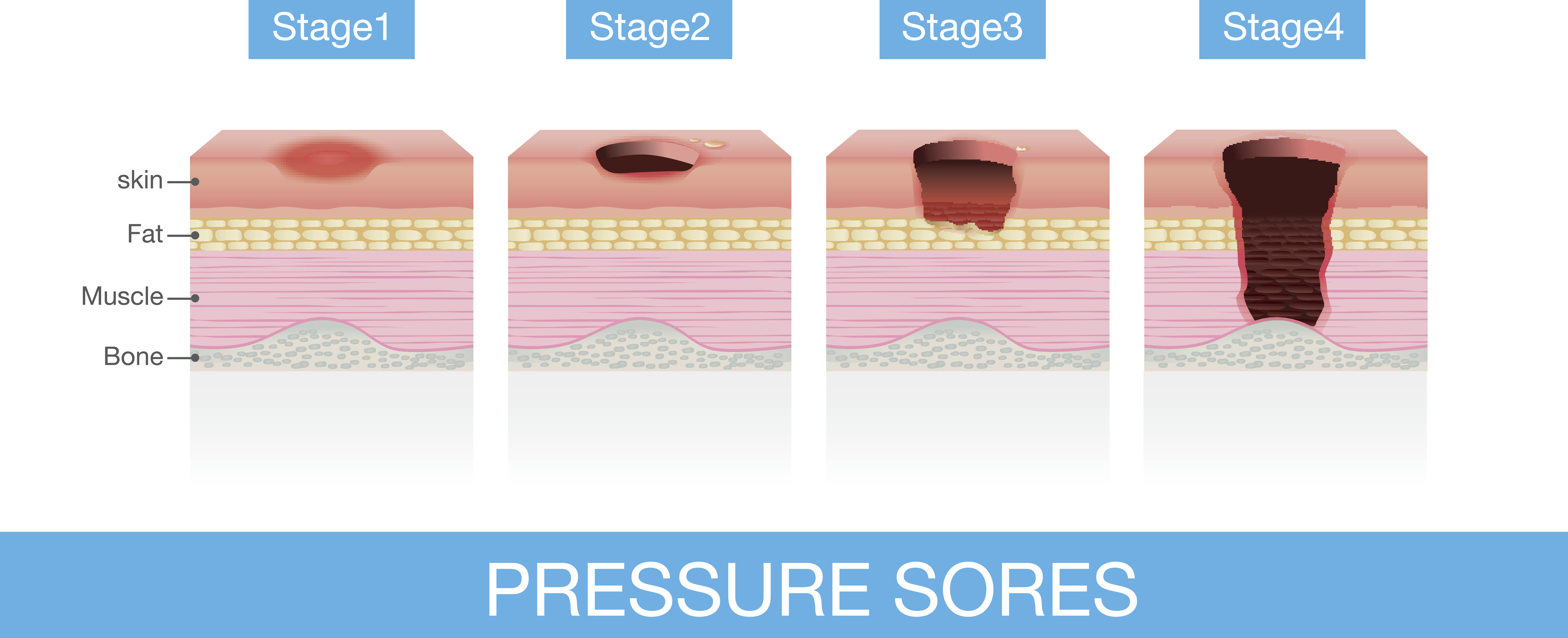

- Stage I-Nonblanchable erythema

- Stage II-Partial-thickness

- Stage III-Full-Thickness skin loss

- Stage IV-Full-thickness tissue loss

- Unstageable-Full thickness skin or tissue loss-depth unknown

- Unstageable-Suspected deep tissue injury-depth unknown (Slachta, 2016).

- Arterial or venous insufficiencies may cause ulcers due to impaired blood flow/oxygenation. Venous ulcers are a result of venous hypertension and occur in the lower legs. Venous ulcers account for 70-90% of all leg wounds. Arterial ulcers are the result of tissue ischemia that is caused by arterial insufficiency. They occur at the most distal end of an arterial branch. Arterial ulcers account for 5-20% of all leg ulcers (Wounds Made Incredibly Easy, 2015).

- Diabetic ulcers are the result of poor circulation to the feet and neuropathies that result in decreased sensation in the feet. The diabetic patient is unable to feel injuries or trauma to the foot and ulcers or wounds result that are often unnoticed until they are serious (Game et al., 2016).

Developmental Implications

Infants and children have skin that is similar to an adult’s in structure, but their function is not fully developed until puberty. Infants are at greater risk of fluid loss due to the increased permeability of their skin. In older children and adults, the muscles contract rapidly to release heat, however a young child’s ability to control temperature is not completely effective until later in life. Infants and young children cannot contract the muscles rapidly or shiver, as they have an inefficient subcutaneous layer. With growth, the child will develop a thickened epidermis. By puberty, the skin may look oily and acne may be apparent due to increased activity of the sebaceous glands. There will be increased subcutaneous fat in females in particular during this time (Jarvis, 2016).

Pregnant women have unique skin alterations, such as increased connective tissue to allow the skin to stretch. These may ultimately result in “stretch marks” on the abdomen, breasts or thighs. Fat deposits are also increased to support maternal reserves during breastfeeding (Jarvis, 2016).

The aging adult may have skin changes related to atrophy of the skin structures. Skin loses its elasticity and starts to fold and sag. By the 70’s and 80’s, the skin is thinner, drier and wrinkled. The epidermis thins and flattens allowing for increased absorption of chemicals into the body. There is a decrease in collagen in the dermis layer which increases the possibility of skin tears and shearing injuries. Sweat and sebaceous glands decrease in number and leave the skin drier with an increased risk for heat stroke. There is a decrease in vascularity of the aging skin, yet a fragility to the vessels that increase bruising from even minor trauma (Jarvis, 2016). If the aging adult smokes tobacco or has sun exposure, there is increased wrinkling, dryness, atrophy and pigment changes which can create a leathery texture to the skin. The lighter skinned an individual is, the more damage is visible from sun and smoke exposure. A wound in an older patient can take much longer to heal and carry a much higher associated risk than a wound in a younger patient (Pilgrim & Schub, 2018).

Keep in mind that older patients will require a longer healing time, especially with lower extremity wounds and their medications could further delay healing time. It is important to consider all patients’ nutritional status, but particularly the older patient.

Risk Factors

As noted above, age can have implications for the healing process due to variations in skin structures and make-up. Further risk factors are related to comorbid conditions and disease processes, nutritional status (including obesity and malnutrition), medications, as well as tobacco and alcohol use. The nurse, along with the interdisciplinary team, must recognize any underlying pathologies that may impair wound healing. This includes assessment for underlying vascular impairments, neuropathies, metabolic disease, connective tissue disease, trauma, cancer treatment, iatrogenic disease, hospital acquired infections, or adverse effects of medications that may guide the plan of treatment (Pilgrim & Schub, 2018). Each risk factor will be examined below.

Disease Processes

- Diabetes-The diabetic patient is at risk for slowed or inadequate wound healing related to elevated blood sugars. Further effects of diabetes include neuropathy, vascular impairment, and a decreased immune response that leads to acute and chronic wounds, particularly of the feet. The patient may be unaware of an injury to their feet or other areas of the body due to reduced sensation secondary to neuropathy. Untreated injuries become gateways for bacterial infiltration. Diabetic wounds may be chronic and take months to years to heal, and others may not heal at all (Chylinska-Wrzos, Lis-Sochocka & Jodlowska-Jedrych, 2017).

- Infection-Wounds are at risk of infection and healing is delayed in the presence of bacteria. Infection contributes to chronicity, morbidity and mortality from wounds. Chronic wounds have the presence of biofilm-associated infections which are characterized as microbes that are attached to a surface and embedded into the wound bed. Various bacterial species can be included in the biofilm but the ones that cause the most impact are the ESKAPE pathogens-Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp (Watters et al., 2015). These bacteria are normal flora on the individual’s outer epidermal layers, yet colonize into the wound bed and lead to wound infections. Each wound is different based on the patient’s colonized bacteria and the location of wound. This biofilm leads to chronic inflammation as the immune system tries to remove the infection, causing damage to the host tissue in the process. This delays healing and promotes the opportunity for further tissue damage and infectious growth.

(Watters et al., 2015, p. 55)

- Immunodeficiencies- The healing process may be impaired in those who are immunocompromised secondary to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, cancer, burns, or immunosuppressive therapies such as corticosteroids and chemotherapeutic drugs. Other factors leading to immunodeficiency are stress, age, malnutrition, surgery, trauma, alcoholic cirrhosis, chronic renal disease, diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus, or AIDS (Schub & March, 2018).

- Vascular Disease- Peripheral vascular disease causes a blockage of arteries that reduces blood flow to the extremities. This reduced blood flow means that oxygen and nutrients cannot reach the tissues, including the skin, and may result in the breakdown of skin and/or diminished healing to wounds found in the periphery (Higson, 2018).

Nutritional Status

- Obesity-Skin irritation and breakdown may occur in the presence of obesity. Pressure injuries may also occur within the obese population. Obesity limits activity, body movement and optimal blood flow. These limitations can lead to pressure sores even when mobility is assisted. Morbidly obese patients often require two or more individuals to reposition or assist with activities of daily living (ADLs) in the home and clinical settings. If the obese individual is also incontinent, the risk of skin breakdown increases further. Microorganisms grow in the moist skin folds of the obese individual and increases the risk of rashes and lesions. Poorly vascularized adipose tissue and increased skin surface area increase the risk of skin injury. With an estimated 40% of adults who are obese in the United States, there is a high prevalence of wounds in this clinical population (Schub & Schub, 2018).

- Extremely underweight patients or those who are malnourished are similarly at risk for pressure wounds and are up to three times more likely to develop a pressure ulcer than obese patients during ICU stays with prolonged immobility. This group has less subcutaneous fat and are more likely to develop pressure from bony prominences than other groups (Hyun et al., 2014).

Dry Skin

Dry skin can lead to breakdown and delayed wound healing. A dry wound bed results in a lengthy healing process and contributes to non-healing wounds. A moist wound environment facilitates rapid re-epithelialization and improves healing rates. Epithelialization is the “formulation of granulation tissue into an open wound, allowing the re-epithelialization phase to take place as epithelial cells migrate across the new tissue to form a barrier between the wound and the environment” (Pastar et al., 2014). The moist environment supports cell migration across the wound surface and decreases the risk of infection as bacteria has difficulty breaking through the moisture barrier. The moisture further assists in the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the wound bed to encourage healing (Lumbers, 2019). Further advantages of moist wound beds is a decrease in pain and subsequent scarring (Deeth & Grothier, 2016).

Medications

- Corticosteroids-Wound healing is impacted by steroid use through multiple mechanisms including contraction, matrix deposition, epithelialization and a decrease in wound tensile strength. Steroids also suppress wound healing by inhibiting the inflammatory response. The epidermis is thinned by steroids and when given over a prolonged time, greatly impact wound healing (Beitz, 2017).

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been shown to have a depressant effect on wound healing while decreasing the granulocytic inflammatory response (Beitz, 2017).

- Chemotherapy-Chemotherapeutics such as cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) and cisplatin (Platinol) block the cell cycle by alkylating DNA nucleotides, and complicate wound healing (Deptula, Zielinski, Wardowska & Pikula, 2019). Chemotherapy drugs inhibit cellular metabolism, cellular division or angiogenesis in order to stop the growth of cancer cells. Unfortunately, this action also influences wound healing by decreasing the ability of tissues to regenerate (Deptula et al., 2019).

Tobacco/Alcohol

- Smoking is known to have ill effects on the body and health in general. Wound healing is impacted by smoking through a decrease in oxygenation, which delays wound healing. Nicotine, tar, nitric acid, hydrogen cyanide, carbon monoxide and aromatic amines are carcinogens found in cigarette smoke known to disrupt inflammatory and reparative cell functions (Ellis, 2018). Smoking is also noted to have an impact on the healing process through an increased risk of infection, rupture of the wound, leakage of anastomoses, wound necrosis and a reduction in the tensile strength of the wound. Additionally, post-operative wounds do not heal well related to decreased vascularity (McDaniel & Browning, 2014).

- Alcohol use has an impact on all body systems and the skin equally is affected. Alcoholism is associated with a higher infection rate for wounds and delays in closure of both surgical and non-surgical wounds. Ethanol seems to impair dermal fibroblast function which play a role in wound healing (Travejo-Nunez, Kolls, & de Wit, 2015). In a study on the chronic use of alcohol in mice, there were 30-50% fewer epidermal immune cells after four weeks of chronic alcohol consumption which is likely to account for the decreased immune response when a pathogenic organism enters the wound (Travejo-Nunez et al., 2015). Excessive alcohol use may lead to chronic malnutrition which will further impair wound healing. Adequate nutrition is vital for wound healing and alcohol use inhibits fat absorption leading to deficiencies in the fat-soluble vitamins, A, D, E, and K. Deficiencies in these vitamins and protein can impair wound healing (Curtis, Hlavin, Brubaker, Kovacs & Radek, 2014).

Wound Healing

The body’s ability to heal itself after an injury or following the development of a wound is a natural restorative response and will be influenced by the source or degree of the injury. Additional factors include the location of the injury, ability of the skin to repair itself, and patient characteristics that will be further discussed (Bryant & Nix, 2016). Wound healing is related to the skin’s ability to heal itself that is achieved through two processes:

- Tissue Regeneration: a process in which damaged tissue is replaced with growth of healthy tissue. In a superficial injury in which the stratum basale remains intact, the epidermis regenerates cells of equivalent type and function.

- Tissue Repair: a more complex healing process which occurs when the dermis is injured and lost tissue is replaced by connective tissue which does not have the same degree of functionality as the original tissue; such as a scar (Health Service Executive [HSE], 2018).

Wounds will heal by one of the following mechanisms:

- Primary closure occurs when the edges of the wound are brought together by mechanical means such as staples, sutures, glue, strips or other devices. Surgical wounds or those with minimal tissue loss allow for primary closure and result in minimal scarring.

- Delayed primary closure is primary closure that is intentionally delayed several days due to wound contamination or impaired perfusion. This type of closure will result in sutures or staples after a 3-6-day delay.

- Secondary closure occurs when the wound is left open to heal gradually by granulation, contraction and epithelialization of the wound. This type of closure is used in cases of excess tissue loss such as burns, ulcers or trauma that are not suitable for primary closure.

- A skin graft is the excision of a partial or full-thickness segment of healthy epidermis and dermis without a blood supply that is transplanted onto a wound to enhance healing and reduce the risk of infection.

- A skin flap is the surgical excision of skin and its underlying structures with blood supply intact that is used to reconstruct or repair a defect caused by the loss of tissue (Peate & Glencross, 2015).

Healing times will vary and depend on the origin of the wound, size, location and risk factors as previously mentioned in certain high-risk groups. Next, we will explore the different types of wounds the nurse and interdisciplinary team may manage (Peate & Glencross, 2015).

Nursing Assessment

Every patient who enters an acute care, home health or long-term care setting must have a skin assessment within 24 hours of admission. This assessment should take place as soon as possible to ensure that all preexisting wounds are carefully identified, documented and appropriate treatment is initiated. An approved skin assessment risk tool should be utilized to identify any preexisting wounds as well as determine the risk for pressure wound development during the inpatient or outpatient admission. It is recommended that a full head-to-toe skin assessment is completed upon admission, which should be repeated daily, upon transfer from a different unit or facility, and with any condition change that may increase the patient’s risk (National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators [NDNQI], 2018).

The Joint Commission (2016) included the prevention of hospital-acquired pressure ulcers in their 2015 Patient Safety Goals in both the acute and long-term care settings. They require the use of a skin assessment tool such as the Braden Skin Assessment Scale. The Braden Scale has been in use since 1988 and is the most commonly used tool for predicting pressure injuries and skin breakdown during hospitalizations or in long-term care facilities. The Braden Scale estimates the risk for pressure injuries by assessing the patient’s:

- Sensory perception

- Moisture

- Activity

- Mobility

- Nutrition

- Friction and Shear

Each category is given a score which are compiled to determine the individual’s risk for skin-related issues during their admission. After determining the risk, interventions are instituted accordingly to decrease the risk and prevent development of skin breakdown (Bergstrom, Braden, Laguzza, & Holman, 1987).

After completing the risk assessment tool and identifying any preexisting wounds, the nurse must perform a focused wound assessment that will determine the plan of action. The initial step is a thorough history taking inclusive of any risk factors that may impede the healing process. Considerations for the initial history taking include systemic disease such as diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, smoking, alcohol use, medications (with focus on NSAIDS and steroid use), adequate nutrition and any other risk factors that may impact healing. Additionally, the nurse will assess the origin of the wound, onset of injury or awareness of wound, and any mitigating factors related to the wound progress including increasing pain, drainage, or severity (Dowsett & Hall, 2019).

Skin assessment tools are important ways to provide consistent care that can be communicated to the entire healthcare team. Several wound care assessment tools are available but this education module will focus on the T.I.M.E.S tool (Tissue, Infection and inflammation, Moisture, Epidermal advancement, and Surrounding skin). This tool has been recognized for its simplicity and ease of use (Dowsett & Hall, 2019).

Table 1. T.I.M.E.S tool for wound assessment | ||

Wound aspect | Clinical Question | Action |

Tissue | Is dead or unhealthy tissue present? Is wound healing possible | Perform debridement |

Infection/Inflammation | Is the wound painful, erythematous, swollen or smelly? | Perform wound irrigation, bacterial swabbing with or without prescription of antibacterials. Medically or surgically control causes of persistent inflammation. |

Moisture | Is the wound wet? If so, why? | Judicious choice of dressings (including negative pressure) |

Epidermal advancement | Are the wound edges healthy and reducing? Are there any barriers to healing? | Pay close attention to surrounding skin care |

Surrounding skin | Is the surrounding skin healthy? | Protect the surrounding skin with dressing and appropriate emollients |

(Ward et al., 2019)

Determining the origin of a wound is an important part of the assessment to predict further complications that may occur. Other factors that should be considered are the location, depth, size and age of the injury along with a pain assessment related to the wound. Wound healing complications may increase based on any of these factors. A careful assessment of the wound and documentation to share with the healthcare team will offer insight to the healing process and allow for early intervention where change in treatment is needed (Driver et al., 2017).

The wound bed and surrounding tissue must be assessed for size and depth of the wound. Measuring devices are available and often a picture of the wound is needed for insurance reimbursement and a tracking mechanism for progress or lack thereof. The measuring device is most often a disposable tool to avoid contamination. Measure the width at the longest distance across the wound and the length at a 90 degree angle to the width. Most healthcare providers use the clock method to determine the reference points such as “12 and 6, 3 and 9” for length and width. To measure the depth of a wound, use a cotton-tipped swab that can be inserted into the deepest part of the wound and mark the distance where it meets the skin edges. Then measure the distance from the end of the swab to the mark made and this is the wound depth. Avoid pushing into the wound bed as organs or vessels could be injured. If obtaining photos of wounds, be sure to obtain a consent for photography to avoid Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) or Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) violations. Follow the policy of your facility with wound care photography acquisition (Jarvis, 2016).

In addition to measurements of the wound, it is vital to give a clear description of the wound appearance including drainage and/or surrounding tissue. The wound bed tissue should be described in relation to color, tissue type, condition of the surrounding tissue and appearance of wound edges. Drainage, if present, should be described with color, odor, presence or absence of moisture or notation of a dry wound bed. In the absence of moisture, the cells involved in healing can’t move across the wound bed and the wound edges dry up and epithelial cells fail to grow over the wound. As a consequence, healing will stop and necrotic tissue will build up (Ward et al., 2019). In contrast, too much moisture can be an equally detrimental issue and cause damage to intact cells at the wound’s edge. It is important to monitor the wound edges to ensure that the skin is smooth and without rolled skin or dry edges. The color of both the wound bed and surrounding skin can indicate concerns. White skin surrounding the wound indicates too much moisture and may cause increased tissue damage. Red skin or inflammation can indicate infection, injury, tape burn, or irritation from wound care products. Typically, erythema over 2-3 cm from the wound edge indicates an infection (Brown, 2018).

Palpate the tissue around the wound to determine if the tissue is hard or soft, as hardened tissue can indicate infection or inflammation. Measure any areas of hardness or induration and document. Wound bed tissue assessment should include appropriate terminology for the wound bed condition. Granulation tissue, fibrin slough or eschar should be managed appropriately to support wound healing and appropriate treatments will be discussed later (Driver et al., 2017).

For pressure ulcers, specific tools should be considered including the PUSH (Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing) tool, which was developed by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP, 2019). This tool considers the length and width, exudate and tissue type, assigning numbers that add up to a total risk score. These scores are plotted on a pressure ulcer healing record and healing graph that helps determine the progress toward healing (Brown, 2018; NPUAP, 2019).

There are numerous resources available from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, 2018) that include clinical guidelines for wound care, tool kits and quality indicators that promote prevention and specific treatment opportunities for a variety of wounds to promote a reduction in incidence and mortality within the health care system.

Diagnosing Wounds

The Interdisciplinary team will diagnose the patient’s wound and initiate appropriate evidence based care. Nurses should thoroughly investigate a wound upon discovery to help determine if the cause is pressure, friction or other courses. In addition, diagnostic testing may be done to determine the optimum treatment plan. Testing could include lab work to determine nutritional status (albumin, pre-albumin, and total protein) or potential infection, imaging studies to determine any underlying injuries such as fractures, ultrasound, doppler, or biopsies as appropriate (Seppanen, 2019).

Treatments

Treatment depends on the nature of the injury and the individual patient risk factors. For example, an elderly diabetic with a pressure ulcer to the foot may be managed very differently from a younger, otherwise healthy person with the same wound. Treatment options vary in cost, availability, and resources accessible by each patient, so careful consideration should be taken to determine the best modality of treatment in collaboration with the interdisciplinary team (Bergstrom, O’Harra & Foster, 2018). Antimicrobials may be used in combination with dressings, and these may include both topical and systemic agents. If antibiotics/antimicrobials are to be used, a wound culture should be obtained first to determine the type of organism, promote effectiveness of the treatment and to reduce the risk of antibiotic resistant organisms. The CDC (2018) reported over 23,000 deaths due to superbugs created by the overuse of antibiotic therapies. Therefore, antibiotic therapy should be limited to two weeks and if there is no progress in that time, further testing should be completed to rule out underlying disease processes. Antimicrobial therapies should be discontinued once the wound infection clears and inflammation has improved (USDHHS, 2018).

Wound cleansing will vary among wound types but can be a vital part of the wound healing process, removing foreign materials, necrotic tissue, excess medication, and bacteria or contamination. Unless contraindicated, wound cleansing should occur with each dressing change. Typical wound cleansing is completed with normal saline, sterile water or a commercial cleaner with varying ingredients. Cleansers should be hypoallergenic and non-toxic for the healthy tissue and should be appropriate to use with subsequent dressings. It is important to follow the manufacturer guidelines for any dressing product (Brown, 2018).

Debridement will be needed for wounds with necrotic tissue so that granulation can occur, and the underlying wound can heal. Granulation is the development of new blood vessels and tissue in a wound during the healing process. Healthy granulation tissue should be pink or red in color, soft, bumpy and raised above the skin’s surface and wet or moist (Dabiri, Damstetter & Phillips, 2016).There are a variety of debridement types including autolytic debridement, enzymatic debridement, mechanical debridement, surgical debridement, and biological debridement.

- Autolytic debridement uses the body’s own enzymes and healing processes to rehydrate, soften and liquefy, then expel the necrotic tissue from the wound. Occlusive dressings are often used to keep the body’s fluids in the wound bed and maintain a moist healing environment for the wound. Dressings used for autolytic debridement include foam dressings, hydrogel sheets, honey dressings, hydrocolloid dressings and amorphous hydrogel. This type of treatment should not be used in infected wounds or those that should be urgently debrided for best outcomes. Wounds with large amounts of necrotic tissue, undermining or tunneling and/or immunocompromised patients should not consider autolytic debridement as well (Caple & DeVesty, 2018).

- Enzymatic debridement or chemical debridement is the process of removing necrotic tissue, cellular debris, wound exudate, and foreign materials to dissolve the necrotic wound tissue. The only approved medication in this category in the United States is collagenase SNTYL ointment. The active ingredient is from the bacterium Clostridium histolyticum and the ointment breaks down collagen in necrotic tissue. This debridement can also be used on burns to remove eschar. Patients receiving this treatment are at an increased risk for systemic infection related to blood contamination with bacteria from the wound bed. Silver and iodine can inactivate collagenase so dressings with these ingredients should be avoided after applying the collagenase ointment (Caple, 2018).

- Surgical debridement is performed by the physician or primary healthcare provider. Wound debridement is the removal of necrotic tissue, cellular debris, wound exudate, or eschar that requires removal from the wound bed to facilitate healing. This is an invasive procedure that uses sharp and sterile instruments to excise the nonviable materials from the wound bed. For wounds that require this type of surgical intervention, the interdisciplinary team will support the procedure as needed and perform subsequent wound care and assessments (Pilgrim & Heering, 2017).

- Mechanical debridement has historically been completed with wet-to-dry dressings but newer forms of this type of debridement are completed through hydrotherapy, pulsatile lavage, or ultrasonic mist debridement which uses acoustic energy to remove nonviable tissue. It is important to monitor for signs and symptoms of infection with debridement. Patients on anticoagulant medications or with underlying coagulopathy may have significant bleeding with mechanical debridement, so extra care should be taken with these individuals. Pain management is very important as this form of debridement can be painful (Moore, 2015).

- Biological debridement, otherwise known as maggot debridement therapy is the use of sterile, medical-grade maggots (fly larvae) to remove necrotic tissue from wound beds. The wound bed is cleaned and sterile maggots are applied to the wound bed and then covered with a mesh-like, air permeable dressing for 1-3 days, after which the dressing and maggots are removed. If further debridement is needed, the process can be repeated. Wounds should never be allowed to close over the maggot larvae, and they should not be left in the wound bed if they die as this increases the risk of allergic reaction or further infection. Maggots used for this treatment are considered contaminated and should be disposed of properly by sealing them in a plastic bag and placing the bag in a biohazard container for incineration (Schub & Walsh, 2018).

Dressings

It is very important that nurses possess a keen awareness and understanding of the various wound types and the appropriate dressings for each. The proper dressing for the wound will support wound healing and promote faster healing times. Dressing types will likely change throughout the healing stages and the nurse will need to assess the wound and update the dressing throughout the trajectory of care. Unfortunately, cost is a considerable factor in determining wound care products when planning treatment. Comfort and usability are important factors to also consider, as the patient or family members may be performing the wound care once the patient is discharged from the health care facility. The frequency of dressing changes should be considered for both staff workload and patient compliance. Newer treatment modalities require less frequent changes and are able to stay in place for longer periods of time with optimal results.

- Gauze and non-woven dressings have been used for wound care for decades, but with the advancement of new materials devised to accelerate healing, these materials are rarely used in modern day wound care. Daily dressing changes are required with these materials in order to manage drainage effectively. Gauze may be useful in the first 24 hours after surgery to manage the drainage, however most surgical wounds are left open to air after the first 12 hours unless there is significant drainage (Brown, 2018). Examples of gauze and non-woven dressings are Kerlix or Curad.

- Absorption dressings are made up of materials that will allow for optimal absorbency and may be used alone or in combination with other dressings. These dressings are typically made of cotton, cellulose or rayon and absorb the wound drainage to avoid maceration of the tissue. Most do not stick to or damage the wound bed, or cause pain upon removal. These dressings are not appropriate for dry wound beds, as they can cause further damage (Sood, Granick & Tomaselli, 2014). Examples of absorption dressings are Optilock or Xtrasorb.

- Alginates are used for highly exudative wounds and contain alginic acid from seaweeds covered in calcium/sodium salts. The dressings are highly absorbent and may contain controlled-release ionic silver. These dressings interact with serum to form a hydrophilic gel in the wound bed. They support a moist wound environment, absorb well and may prevent microbial contamination (Sood et al., 2014). Examples of alginate dressings are Maxsorb or Megisorb.

- Skin substitutes are made to mimic human skin and are useful on hard to heal wounds. They incorporate into the healing process but are non-toxic and do not transmit disease. Some research shows that skin substitutes decrease healing time and offer improved options for diabetic wound care (Santema, Poyck & Ubbink, 2016). Examples of skin substitutes are Alloderm or Dermagraft.

- Bioactive dressings are used to improve wound healing and are derived from natural sources, proteins or tissues. Examples are collagen dressings and medical-grade honey. These products are especially useful in burns and hard-to-heal wounds (Wood, 2018)

- Hydrocolloid dressings are moisture-retentive dressings used to protect wounds with a small to moderate amount of drainage. These are most often used to treat non-infected Stage I through Stage IV pressure injuries, partial to full-thickness wounds, abrasions and/or necrotic wounds (Smith & Caple, 2019). Examples of hydrocolloid dressings are DuoDerm or Nu-Derm.

- Foam dressings can be constructed from either foam that draws in fluid and physically expands as it retains the drainage or pseudo-foam that contains absorbent materials such as viscose and acrylate fibers designed to hold extra fluid. These are best for wounds with moderate to heavy drainage. Both can be used as a primary or secondary dressing on wounds and can be left in place for up to seven days. Most are non-adhesive and can easily be used on those with allergies to adhesives. There are antimicrobial foam dressings that can be used on infected wounds as well (Mennella & Schub, 2017). Examples of foam dressings are Aquacell Foam or Optifoam.

- Hydrogel dressings contain a high water/glycerin content within a gel base and are used to provide moisture to the wound bed. The moist environment facilitates debridement of necrotic tissue and tissue granulation. Amorphous hydrogel can be applied in a layer over the wound surface or a hydrogel impregnated gauze can be used to fill in dead spaces in deeps wounds such as stage 3 or 4 pressure ulcers. These dressings should not be used with moderate to heavy wound exudate or when the goal of care is to maintain dry eschar. Hydrogel dressings can contain allergens such as iodine, silver or sodium carboxymethyl cellulose and should not be used in patients with known sensitivities or allergies to these products (Caple & Walsh, 2018). Examples of hydrogel dressings are Aquasite gel/sheets or Derma-gel.

- Hydrofiber and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose dressings are used for wounds that may require packing as they are available in sheets or ribbons. These products combine with the wound exudate and produce a hydrophilic gel that maintains a moist wound environment. These dressings should not be used on dry wounds (Inoue et al., 2016). Examples of hydrofiber dressings are Biosorb or Aqua-cell.

- Hydrophilic wound fillers can be used with negative pressure systems to facilitate adequate drainage of wound secretion, reduce tissue edema and simultaneously increase tissue perfusion. There is typically 30-180 mmHg of negative pressure in the wound cavity to promote wound healing (Klein et al., 2015). Examples of hydrophilic wound fillers are multidex gel/powder or Gold Dust.

- Contact layers are non-adhesive layers that are placed on a wound bed to allow drainage to flow through but keep the secondary dressing from contacting the wound bed. These may be used on burns, grafts or other wounds to prevent damage to the underlying tissue with dressing changes. They may be used in tandem with topic medications or wound fillers (Smith & Caple, 2019). Examples of contact layers are Dermanet, Telfa, or Adaptic.

- Antimicrobial dressings are an important part of routine care for an infected wound, particularly diabetic foot ulcers. These dressings work to decrease the number of bacteria in the wound bed and decrease the need for systemic antibiotics. The antimicrobial materials may be impregnated into other dressing types such as hydrogels or foams to decrease the bacterial count in the wound. Care must be used to choose the appropriate type of antimicrobial dressing that will support wound healing. Their use should be limited to two weeks to avoid resistant organisms (Bishop, 2018). Examples of antimicrobial dressings include Optifoam Ag, Aquacell Ag, Acticoat, Iodoflex, Iodasorb or others.

- Transparent films may be used to secure other wound care products or alone for clean, dry wounds with minimal drainage. These dressings allow for visualization of the wound and work well on areas that need to be waterproofed. They also use the body’s own fluids to support debridement. Transparent dressings should not be used on wounds with moderate to large amounts of drainage (Schub & Mennella, 2018). Examples of transparent dressings are Op-Site and Tegaderm.

- Combination dressings are those consisting of several layers that have varied dressing types within the layers. Some may have adhesive borders while others may require tape or an outer dressing to secure it (Dhivya, Padma, & Santhini, 2015). Examples of combination dressings include Stratasorb and Dermarite.

While this is a long list of dressing types and examples, it is by no means exhaustive of the vast resources for wound care. The nurse and interdisciplinary team must consider all aspects of the patient’s needs and resources and determine the best plan of action in collaboration with the patient.

Nutrition for Patients with Wounds

Nutrition is a basic requirement of the human body that allows for normal day to day functioning. Patients who have wounds have higher nutritional needs than the average person. Wound healing is a complex process and relies on the coordination and internal regulation of various metabolic processes to promote epithelialization within the injured tissue. There are typically three phases that overlap each other which include: inflammation, proliferation and epithelialization, and remodeling (Bishop, Witts & Martin, 2018).

Nutritional factors should be considered in all diseases but optimal nutrition should be considered in a timely manner with wound healing to promote the best outcomes. An optimal diet for those with a wound should be high in proteins and amino acids with sufficient amounts of vitamin A, vitamin B complex, vitamin C and Vitamin E; iron, zinc and copper; and fats and carbohydrates (National Health Service [NHS], 2015). Early referral to a dietician can facilitate an appropriate dietary intake to support wound healing. A dietician consult should be considered for any patient that is high-risk for nutritional imbalances or deficiencies or have high-risk co-morbidities such as diabetes, renal disease obesity, liver disease or any disease that affects the body’s ability to process or eliminate nutrients (Bishop, et al., 2018).

All patients with wounds should consume a diet that consists of 20% protein, 40% vegetables/fruit and 40% carbohydrates. In most patients, this diet provides the body with the nutrients required to promote timely wound healing. Supplements may be needed to support nutritional needs in some patients during the wound healing process, and the dietician and primary healthcare provider may collaborate to develop an ideal treatment plan to ensure adequate dietary intake (Bishop et al., 2018)..

Pain Control

Pain is an expected side effect of many wounds, and many patients report the pain they endure during wound care is as painful as the initial injury (Chester et al., 2016). Depending on the severity and location of the wound, the pain may or may not be a significant problem. Burns are particularly painful to care for and require ongoing pain relief. Factors that increase pain are depth of the wound, structures involved, infection, and other injuries or conditions that co-exist with the wound. The nurse should complete a pain assessment to determine all aspects of the pain, including location, exacerbating and relieving factors, quality of pain, and severity based on a numerical pain scale. Administration of pain medications is important along with other considerations that may decrease the intensity and length of pain:

- Distractions may help to decrease pain including watching television, playing games, or reading materials.

- The nurse should space out care to give the patient uninterrupted rest time in a quiet environment.

- Reduce anxiety levels with music therapy or other guided imagery techniques.

- The nurse should help position the patient for comfort during any procedures or dressing changes.

- The nurse should limit the number of dressing changes where possible, leaving the dressings in place for longer periods whenever possible.

- The nurse should help determine dressing types that avoid adherence to the wound bed or tapes and adhesives that pull at the wound.

- Allow the patient to choose times for treatments or dressing changes to create a feeling of independence and decrease anxiety.

- Consider alternative therapies such as hypnosis to reduce pain (Chester et al., 2016).

IV, IM and PO medications will be utilized to manage pain prior to wound care and dressing changes. The patient should be pre-medicated prior to dressing changes at an appropriate time interval prior to scheduled debridement or other painful wound healing dressing changes. While pain medications including opioids may be used during dressing changes and for wound debridement, careful consideration of the adverse risk for addiction should be openly discussed with the patient and healthcare team to determine the best options for positive outcomes (Chester et al., 2016).

Sutures, Staples and Surgical Glues

Sutures may be present for surgical wound or accidental injury wound closure. In either situation, the nurse must monitor the suture line for approximation of the skin, signs of infection and for appropriate healing. Suture materials have changed substantially in the past decade and wound closures may have a multitude of appearances. Check with facility policies and procedures on exact wound care for individual methods. However, suturing and staples are painful for the patient and will require local or other anesthesia prior to the closure. Most suture materials are synthetic and may be absorbable or non-absorbable. It is important to differentiate so that proper instructions are given to the patient for follow-up care. Deep wounds may require sutures to reduce skin tension and reduce the risk of hematoma formation. Superficial sutures are used to enable functional closure with minimal scarring for cosmetic purposes in areas like the face.

Staples are generally only used for superficial wounds but are quick to insert. Local anesthesia may be needed, but are not suitable for areas such as the face. There is less infection associated with staples since they do not form a tract between the wound edges. Most staples are made from stainless steel or titanium and should not interfere with an MRI, but if other injuries are suspected, the radiologist should be consulted to ensure there will be no interference from the staples or if other closures would be best.

Surgical glues are used to close wounds and are very effective in the pediatric setting where fear of needles is more prevalent. Surgical glue is quick to apply and provides excellent cosmetic outcomes. Some wounds are not appropriate for the glue, as wound margins must be apposable and dry. This may not be the case with traumatic injuries. Glues work well with scalp wounds and fewer cosmetic complications occur with adhesives (Bonham, 2016).

Vaccinations

Contaminated wounds or those that are not sterile, including bites, puncture wounds, skin tears, abrasions, or lacerations may have exposure to the bacteria Clostridium tetani which causes a tetanus infection. Tetanus or “lockjaw” as it is often called, is caused by the exotoxin produced by this bacteria and causes serious nervous system effects including the tightening of the jaw muscles that make it hard to breath, open the mouth or swallow. This disease is not contagious but brought on by injuries that are usually from deep puncture wounds or cuts. Patients with burns or dead skin are also at risk (USDHHS, 2019).

The CDC recommends that babies and children receive the diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine at 2 months, 4 months, 6 months, as well as boosters at 15-18 months and again at 4-6 years of age. Preteens and teens should get one dose of the tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis (Tdap) vaccine between 11 and 12 years of age. Pregnant women should have a Tdap during their third trimester of pregnancy and adults should have a tetanus booster (Td) every 10 years. For patients who are injured with one of the wound types discussed in this section, a Td booster is important and/or tetanus immune globulin for immediate protection in those who are not current in their tetanus vaccines or who have never been vaccinated against tetanus (USDHHS, 2019).

Hepatitis B vaccines should be administered for patients who have been bitten by known carriers of HBV or in instances where the bite status is unknown. The vaccine is administered in three doses over a period of six months. The patient should also be given hepatitis B immune globulin (IG) immediately at the time of injury for protection from disease (USDHHS, 2019).

HIV may be transmitted through bites. Prophylaxis with antiviral treatments should be administered to decrease the chance of active infection. This regimen includes multiple drugs used in combination to prevent replication, production and ability to use host tissues by the virus (USDHHS, 2019).

Rabies could be transmitted via animal bites. If the animal’s status of infection cannot be confirmed, rabies immune globulin and rabies vaccines should be administered as soon as possible. Treatment should begin as quickly as possible after the initial injury. If a rabies infection is identified, the local and national health departments should be notified as there is risk to the general animal population as well as humans (USDHHS, 2014).

Alternative Treatment Options

There are many available treatment options for wounds and there are often changes in the treatment plan along the road to healing in order to provide the optimal healing environment. Options that may not be considered immediately but may be part of the overall interdisciplinary plan of care include skin grafts, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, negative pressure wound therapy and/or surgery. These treatments may be used to promote wound healing and decrease complications of the healing process.

- Skin Grafts are performed to promote healing of large burns, wounds and venous or pressure ulcers. They may also be performed to restore skin that has been removed during surgery or after a serious skin infection. The graft may be taken from the patient’s own body, which is known as an autograft. This type of graft has the fewest complications related to rejection. Other grafts may be taken from another human source such as a cadaver, an animal source or a synthetic tissue (Buck, 2018). Grafts should be placed on tissue that will support growth and adherence. Grafts placed on bone, tendons or nerves will likely be unsuccessful as there is a limited blood supply to support the growth of the graft. Wounds with necrotic tissue, eschar or those with high bacterial counts are not supportive of graft success either. Factors that increase complications with grafts are patient age (pediatric and geriatric patients), smoking, diabetes, poor overall health or the use of certain medications. There are three types of graft techniques including split-thickness grafts, full-thickness grafts, and composite grafts. Depending to the technique, the graft may take longer to heal. Skin graft procedures can be very painful, so anesthesia should be utilized to prevent pain during the surgery. Pain control after the procedure can be managed with oral, IM or IV pain medication. Skin tissue engineering is a newer procedure that uses stem cells to produce skin products that can replace the damaged tissue (Kaur, Midha, Giri & Mohanty, 2019).

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) may be used on chronic wounds to promote wound healing. Wounds that are not healing are typically hypoxic and increasing oxygen tension and/or pressure by various methods can stimulate healing. HBOT promotes muscle and nerve regeneration by stimulating angiogenesis, or the development of new blood vessels. The treatments can be done on limbs that are placed in a limb-encasing device or a full-body chamber. HBOT has been in use for over 40 years and should be part of an interdisciplinary team with a comprehensive plan of care for wound healing that includes strategies for large vessel disease, glycemic abnormalities, nutritional deficiencies, infection and the presence of necrotic tissues (Kaur et al., 2019). Contraindications for HBOT are asthma, claustrophobia, COPD, Eustachian tube dysfunction, pacemaker, high fever, epidural pain pump, pregnancy, seizures and upper respiratory infections. Absolute contraindications would include a pneumothorax, sever respiratory disease, recent chemotherapy and other drugs including disulfiram (Antabuse) or mafenide (Sulfamylon) (Kaur et al., 2019).

- Negative pressure wound therapy is also called vacuum-assisted closure and is a method of applying suction or negative pressure to the wound bed. This promotes healing of the wound by removing excess drainage, stimulating vascularization and supporting the closure of wound edges or margins. Negative pressure is applied to create a mechanical stress that promotes growth factor expressions, angiogenesis and granulation tissue growth. The negative pressure helps to open the capillary beds and draw blood to the area of the wound. In addition, the negative pressure aids in healing by reducing edema and bacterial colonization and providing a moist wound bed that promotes healing. This type of treatment is most often used on deep or full-thickness wounds and/or chronic wounds such as pressure injuries and diabetic foot ulcers. It may also be used to prepare a wound bed for skin grafts. Pain is commonly reported as an adverse reaction and should be proactively managed during treatment. This treatment should not be used in individuals who are at high-risk of bleeding as life-threatening hemorrhage could result (Kaur et al., 2019).

- Surgery may be indicated for wounds that have not responded to other types of treatment, if there is a major infection, or the wound has not produced granulation tissue and growth needs to be stimulated. These surgeries may include skin graft or flap replacement, incision and drainage (I and D) of infected wounds, surgical debridement of necrotic tissue, or surgical correction/removal of other complications that may occur during the healing process. Non-healing wounds or those that are inadequately perfused should not be surgically debrided as this may lead to further complications including necrosis or enlargement of the wound bed. This procedure, as with any surgery, can be quite painful and appropriate pain management should be part of the treatment plan (Pilgrim & Heering, 2017).

Prevention of Wounds

A great deal of time, effort, and money are spent on caring for patients with wounds in both the clinical and community settings by the interdisciplinary team. Additional education should be focused on prevention techniques to help reduce the number of wounds annually. Nurses are able to educate patients, particularly those at highest risk for injury, on preventative measures that are feasible for them and their family.

Abrasions, lacerations, and/or punctures

- Wear shoes to avoid stepping on sharp objects or items that can cause foot injuries.

- Carry knives and/or scissors pointing downward away from the body.

- Keep sharp objects away from children.

- Avoid picking up broken glass or sharp metal with bare hands.

- Promote the use of helmets and knee/elbow pads for protection when riding bikes, skating or using any motor devices such as motorcycles.

- Place children in appropriately sized car seats that have been placed in the vehicle per manufacturer directions.

- Avoid risky behaviors that promote injury.

Bites

Children and adults should be taught safe practices around animals, and some recommendations are as follows:

- Avoid animals that may display aggressive behaviors or those that are unknown to the child or adult.

- Children should not make quick movements toward animals or provoke them.

- Avoid leaving children unattended with animals, even family pets.

- Vaccinate all household animals for rabies and other infectious diseases per state guidelines.

- Seek treatment immediately if a child or adult is bitten by an animal or if any signs of infection occur (USDHHS, 2014).

Burns

Burns may be prevented by educating the public to do the following:

- Turn off electrical currents before attempting home repairs.

- Keep outlets covered with protective coverings if small children are in the home.

- Repair or discard frayed electrical wires immediately.

- Keep temperature on water heater set below 120 degrees.

- Avoid wearing loose clothing while cooking.

- Turn pot handles away from the front of the stove and keep children away from the burners of a hot stove.

- Keep hot drinks away from the edge of tables and counters.

- Do not allow appliance cords to dangle over the counter edge (American Burn Association, 2015).

Pressure Injuries

Pressure injuries are completely preventable in the presence of good nursing care and an interdisciplinary team focused on nutrition, activity and proper hygiene (NPUAP, 2019). Nursing care of patients who are immobile or physically impaired due to an acute or chronic illness should include:

- Turning the patient every two hours unless contraindicated.

- Keeping the patient clean and dry at all times.

- Keeping bed linens free of wrinkles and dry at all times.

- Performing daily skin assessments by the nurse or more frequently if patient is incontinent.

- Utilizing appropriate pressure relief devices including mattress toppers, pillows and underpads.

- Integrating wound care experts into the interdisciplinary team if any areas of breakdown occur.

- Consulting dietary/nutrition services to ensure proper nutrition.

- Utilizing incontinence products if indicated. Barrier creams are often use as prophylaxis in the inpatient setting at any sign of erythema (NPUAP, 2019).

Skin tears

Nursing staff should focus on prevention of skin tears, especially in the geriatric population. The following actions should be taken to prevent skin tears:

- Encourage the patient to wear long sleeves and/or pants to protect their arms and legs from skin tears.

- Ensure that sharp edges on furniture are out of the way when moving the patient from bed to chair or ambulating.

- Have proper lighting in the room to reduce the risk of injury with furniture or other devices.

- Maintain adequate nutritional status and hydration.

- Educate the staff and family on proper handling and transferring of patients to prevent injury such as a shearing force.

- Use a lift sheet or transfer device to avoid friction or shearing force to skin.

- Add padding to bedrails, wheelchair arms and leg supports.

- Support dangling arms and legs with pillows or blankets.

- Apply lotion to skin to keep moist after bathing or incontinence care.

- Avoid tapes or adhesives that can tear the skin (Schub, 2018).

Diabetic foot ulcers

Nurses should spend time to teach the diabetic patient and family about good foot care. The mnemonic “BE SMART” is used to drive home the importance of proper foot management in diabetic clients. This stands for Be aware of risk factors; Educate patients and healthcare providers; Structured clinical assessment; Metabolic evaluation and management; Assessment of Risk; Team care (Morey-Vargas & Smith, 2015). Teach all clients the following:

- Encourage patients to control their blood glucose level by eating a healthy diet, monitoring their blood glucose regularly, maintaining an exercise regimen and taking all medications as prescribed.

- Patients should see their primary healthcare provider at least annually and as needed.

- Patients should see their podiatrist for inspections and regular care of their feet. This may vary from every three months to annually.

- Patients or caregivers should perform daily foot inspections.

- Patients should wear shoes that fit well.

- Patients should be instructed to keep the area between their toes dry and avoid lotions.

- Patient should be encouraged to wear cotton socks (Engelke & Schub, 2018).

Vascular ulcers

Both venous and arterial disorders can lead to ulcers. Prevention will vary based on the severity of disease that is present in the individual. The following strategies should be taught to all patient with peripheral vascular disease:

- The nurse should advise smoking cessation.

- The nurse should advise careful glycemic control.

- Oral anticoagulation therapy may be indicated.

- Patients should maintain a regular, structured exercise program as approved by their primary healthcare provider.

- The patients should obtain routine health check-ups.

- Patients should engage in daily inspections of their feet and legs (Gerhard-Herman, 2017).

Legal Implications for the Nurse

Good nursing care can prevent many wounds, including pressure injuries. Nurses have the ability to prevent wounds through prudent care and assessment to identify those at increased risk and provide early intervention. In stark contrast, the nurse may be responsible for wounds that are acquired within the healthcare setting, leading to potential lawsuits and litigation. In the United States, there are thousands of lawsuits each year linked to poor nursing care, including the failure to provide a safe environment and any associated injuries. Through delivery of safe care and vigilant prevention practices, the nurse can avoid costly situations that lead to poor patient outcomes and potential litigation (Brown, 2019). Nurses have a responsibility each time they accept a patient assignment to provide quality care. This includes doing no harm to a patient and following the policies and procedures of their organization, along with adhering to the nurse practice act within the state they are practicing. Nurses should obtain a copy of their state’s nurse practice act at their state board of nursing website, review the policies and procedures manual in their workplace and understand the nursing scope of practice in their state.

Wound Care Certifications and Organizations

Nurses often seek certification in their area of expertise and wound care is no different. While all nurses are expected to deliver safe and effective care to patients with wounds, there are higher level certifications for those wishing to become an expert in this area. Being certified in wound care offers a higher level of care to your patients and offers additional credibility for your organization. The following organizations certify and support nurses who work in wound care:

- Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing Society (WOCN, 2019) which offers the Wound, Ostomy and Continence (WOC) certification.

- National Alliance of Wound Care and Ostomy (NAWCO, 2019) which offers the Wound Care Certification (WCC).

- American Board of Wound Management (ABWM, 2019) which offers the Certified Wound Specialist (CWS).

- The American College of Clinical Wound Specialists (ACCWS, 2019).

Summary

As discussed in this lesson, nurses play multifaceted roles in the interdisciplinary team when caring for patients who are at risk for wounds or for those who have wounds upon entry to the healthcare system. Nurses function as coordinators of care, educators, advocates, and protectors of patients under their care. While we do not control the risk factors that our patients bring to the table, such as smoking, obesity, diabetes or other poor lifestyle habits or conditions, we are able to control aspects of the environment in which the care is delivered; striving to prevent skin tears, pressure injuries, MASD or hospital-acquired infections. Nurses have an obligation to remain knowledgeable of evidence-based treatment options and to serve as leaders in the field through the acquisition of specialty certifications. As the world’s most respected profession, patients and their families look to nurses for advice and guidance on their care; often at the most critical points in their lives when their health has declined. The advice we provide should be current and based on the best available evidence.