About this course:

To impart an evidence-based update on food allergies and sensitivities, emergency treatment of an individual having a reaction to a food allergy, and long-term management of individuals with food allergies.

Course preview

According to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID, 2018), the lead institute at the National Institutes of Health, “food allergies are a condition that affects approximately 5% of children and 4% of adults in the United States. In a person with a food allergy, the immune system reacts abnormally to a component of a food—sometimes producing a life-threatening response” (para. 1). Food allergy symptoms are most common in babies and children, but they can appear at any age (American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, 2014). According to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine [NASEM], 2017), “there are a few specific foods that comprise the majority of allergens responsible for allergic reactions around the world. These include milk, egg, peanut and or tree nuts and seafood” (p. 88).

In 2010, Boyce, etal., in collaboration with the NIAID, created the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in the United States. The document is considered a gold standard of reference for food allergy related content. According to Boyce, etal., (2010), an allergic response can be mild (urticaria) to severe (anaphylaxis). Currently, there are no guaranteed therapies available to prevent or treat a food allergy: the only reliable option for the patient is to avoid the food allergen completely (ACAAI, 2014).

Clinical studies are ongoing in patients with food allergies to help develop a tolerance to a specific food (ACAAI, 2014). Unfortunately, there is still a limited understanding of the prevention of food allergies (NASEM, 2017). Regardless, “having a food allergy is a chronic disease that can influence a person’s quality of life throughout the lifespan and, in some unfortunately individuals, lead to death” (NASEM, 2017, p. 20).

Epidemiology

Gathering data on the prevalence of true food allergies is a challenge to researchers; however, experts believe that there has been an increase in the number of people diagnosed with food allergies. They agree this is unlikely to be due to an increase in awareness or improved diagnostic tools and truly indicates an increase in people with allergies. Underlying reasons are still being researched. As a result, there is a great deal of concern from medical specialists, educational settings, and families regarding the prevention and management of life-threatening adverse reactions (NASEM, 2017).

Definitions

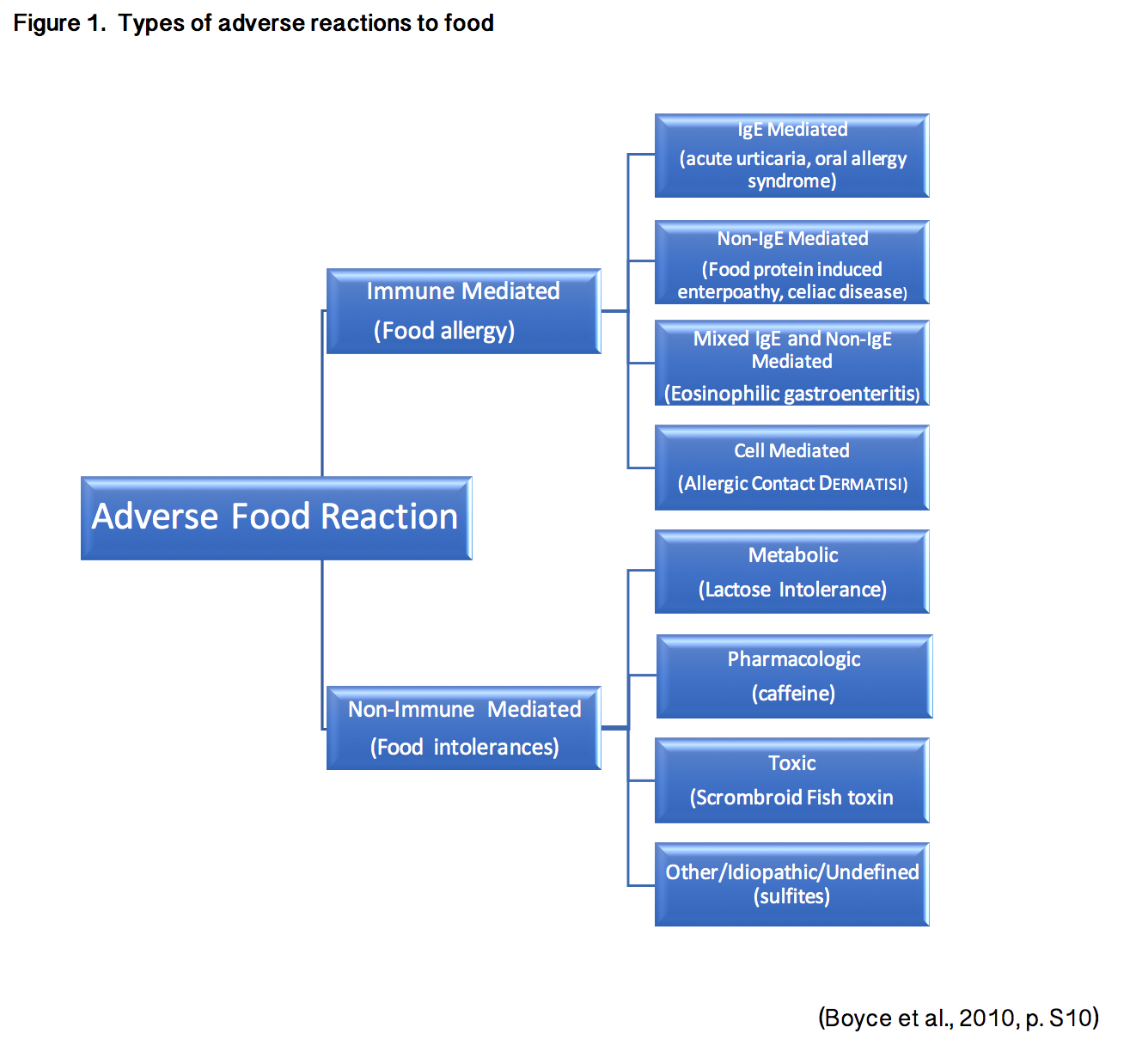

According to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI, 2019), “a food intolerance, or a food sensitivity occurs when a person has difficulty digesting a particular food. This can lead to symptoms such as intestinal gas, abdominal pain, or diarrhea” (para. 1). A food intolerance has no immunologic response.

A food allergy is “an adverse health effect arising from a specific immune response that occurs reproducibly on exposure to a given food” (Boyce et al., 2010, p. S8). Food allergies can be either IgE-mediated or non-IgE-mediated, but IgE-mediated reactions are most common (NASEM, 2017). See Table 1 below, for symptoms by body system that may occur as a direct result of a food allergy.

Table 1. Symptoms of Food Induced Allergic Reactions

Target organ | Immediate Symptoms | Delayed Symptoms |

Cutaneous | Erythema Pruritus Urticaria Morbilliform eruption Angioedema | Erythema Flushing Pruritus Morbilliform eruption Angioedema |

Ocular | Pruritus Conjunctival Erythema Tearing Periorbital Edema | Pruritus Conjunctival Erythema Tearing Periorbital Edema |

Upper Respiratory | Nasal Congestion Pruritus Rhinorrhea Sneezing Laryngeal Edema Hoarseness Dry Staccato Cough | |

Lower Respiratory | Cough Chest Tightness Dyspnea Wheezing Intercostal retractions Accessory Muscle use | Cough, Dyspnea Wheezing |

GI (oral) | Angioedema of the lips, tongue or palate Oral pruritus Tongue Swelling | |

GI (Lower) | Nausea Abdominal pain Reflex Vomiting Diarrhea | Nausea Abdominal Pain Reflex Vomiting Hematochezia Irritability and food refusal with weight loss (young children) |

Cardiovascular | Tachycardia Hypotension Dizziness Fainting Loss of consciousness | |

Miscellaneous | Uterine Contractions Send of impending doom |

(Boyce et al, 2010, pS19)

Per the NIAID (2011), “milk, egg, and peanut account for the vast majority of IgE-mediated reactions in young children, whereas peanut, tree nuts, and seafood (fish and crustacean shellfish) account for the vast majority of IgE-mediated reactions in teenagers and adults. The symptoms of an IgE-mediated food allergy almost always occur immediately after eating the food. However, an allergic reaction may not occur after exposure if a very small amount of the food is eaten or if the food, such as milk or egg, is extensively heated on the stovetop or baked in the oven” (p.9).

See Table 2 below for an outline of the differences between the two types of allergic reactions and how they are predicted to effect the patient. Provides additional details on the cause and nature of allergic reactions to food and intolerances. Most importantly, what the patient or medical provider needs to be aware of in order to help the patient differentiate between a true food allergy versus an intolerance.

Table 2: Overall Differences Between IgE- and Non-IgE-Mediated Food Allergies

Class | IgE-Mediated (i.e., Anaphylaxis) | Non-IgE-Mediated (i.e., FPIES) |

Time to onset of reaction | Immediate | Delayed |

Volume of allergen usually required for a reaction | Small | Variable |

Typical symptoms | Urticaria | Diarrhea |

Common diagnostic procedures | Above signs or symptoms by history or oral food challenge | Sometimes can attempt home-based elimination and rechallenge sequence; some requir

...purchase below to continue the course |

(NASEM, 2017, p.41)

Two additional terms related to food allergies are FPIES (Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome and EoE (Eosinophilic Esophagitis). The definitions are included for reference but will not be discussed in further detail within this module.

“FPIES is a delayed food allergy affecting the gastrointestinal tract leading to vomiting and diarrhea” (AAAAI, 2019, para. 1). “FPIES allergic reactions are triggered by ingesting a food allergen. Although any food can be a trigger, the most common culprits include milk, soy, and grains. FPIES often develops in infancy, usually when a baby is introduced to solid food or formula” (AAAAI, 2019, para. 2).

EoE is a chronic allergic condition causing inflammation of the esophagus. In EoE, “large numbers of eosinophils are found in the tissue of the esophagus. The symptoms will vary by age. In infants and toddlers, you may notice that they refuse their food or are not growing properly. School-age children often have recurring abdominal pain, trouble swallowing or vomiting. Teenagers and adults most often have difficulty swallowing, particularly dry or dense, solid foods. The esophagus can narrow to the point that food gets stuck.” (AAAAI, 2019, para. 2) Most research suggests that the leading cause of EoE is an allergy or a sensitivity to particular proteins found in foods. Many people with EoE have a family history of allergic disorders such as asthma, rhinitis, dermatitis, or food allergy (AAAAI, 2019).

Please reference Figure 1 for a pictographic explanation of the different types of food allergies and food intolerances.

Diagnosis

According to the Mayo Clinic (2017), diagnosing a food allergy is a multi-step process with no “perfect” test to confirm or rule out a food allergy. The initial step is a complete history with a healthcare provider to detail which foods, what quantity, and the severity of the reaction with exposure to the food. Additional discussion of family history of allergies should occur as well. The healthcare provider will then determine if other medical conditions may be causing the symptoms (Mayo Clinic, 2017).

The initial diagnostic test is a skin prick test. The suspected allergen or multiple allergens will be injected directly under the surface of the skin. If an allergic reaction occurs, a raised bump or reaction will occur at the site. If a skin test is not ideal or available, a blood test may be done. The blood is sent to a laboratory to evaluate for the presence of allergy-related antibodies known as IgE (Mayo Clinic, 2017).

A less invasive option to determine a food allergy or sensitivity is an elimination diet. Elimination diets involve completely avoiding suspected foods to determine if symptoms resolve. This is not the most accurate methodology and is not recommended in patients with a history of severe reactions, such as anaphylaxis, to certain foods. Unfortunately, an elimination diet will not distinguish between food allergy and food intolerance (Mayo Clinic, 2017).

To confirm the diagnosis, an allergist may perform an oral food challenge. Food challenges are done by consuming the food in a medical setting to determine if the suspected food causes a reaction. “The test carries a risk of allergic reactions and anaphylaxis, and so caution, content monitoring, experienced personnel and equipment, and medications for managing reactions are required. Feeding a small amount of the suspected allergen and gradually increasing the amount mitigates some risk. The test is stopped at the judgment of the supervising health professional due to the onset of symptoms or at the request of the patient” (NASEM, 2017, p. 108).

Lifelong Management of Food Allergies

There is no cure for a food allergy. Once the specific food allergy has been diagnosed, the only method to prevent complications is complete avoidance. This is true for all types of food allergies, including IgE-mediated and non–IgE-mediated food allergies (Boyce et al., 2010). Patients, care providers, and all persons responsible for preparing or obtaining foods for the patient should be educated on how to read ingredient labels to avoid specific food allergens (ACAAI, 2014). Nutritional counseling may be beneficial as well.

Fortunately, some persons may have relief from their food allergies as they age. Table 3 (below) provides data regarding hopeful resolution of food allergies.

Table 3: Natural Course of Common Food Allergies

Food/Allergen | Likelihood of Resolution |

Milk, egg, wheat, or soy | 70-80% resolve by early-late childhood |

Peanut | 20% resolve during childhood |

Tree nut | 10% resolve during childhood |

Fish, shellfish, seeds | Less certain, but likely similar to tree nuts (above) |

(Savage et al., 2016)

As stated previously, there is no cure for a food allergy. Fortunately, there has been some success utilizing Oral Immune Therapy (OIT) as a method of preventing life-threatening reactions. Absolute food avoidance is a very challenging task, placing people with severe food allergies at great risk for anaphylaxis and death. Oral Immune Therapy exposes participants to minute amounts of the allergen initially. The goal is to gradually increase the dosing of the food allergen in hopes of improving tolerance to a safe level. Patients must still be vigilant about avoidance of the allergen; however, if accidental exposure occurs, their reaction is ideally less severe. This eliminates the risk of anaphylaxis or death. Studies have been conducted on the efficacy of starting OIT earlier in childhood, demonstrating good outcomes. The option of participation in OIT should be given to patients with severe food allergies to improve safety and quality of life (Anagnostou et al., 2014; Vickery et al., 2017).

Management of food allergies in schools is another critical area that must be addressed. In 2011, Congress passed the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act to “improve food safety in the United States. The goal was to shift from a response plan to a prevention plan” (CDC, 2013, p. 3). As a result, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Education created the Voluntary Guidelines for Managing Food Allergies in Schools and Early Care and Education Programs to help guide management of food allergies and severe allergic reactions in children while in institutionalized care.

According to the CDC (2018), “the guidelines focused on recommendations for each of the five priority areas that should be addressed in each school’s or early care and education program’s Food Allergy Management Prevention Plan (FAMPP):

- Ensure the daily management of food allergies in individual children.

- Prepare for food allergy emergencies.

- Provide professional development on food allergies for staff members.

- Educate children and family members about food allergies.

- Create and maintain a healthy and safe educational environment.” (CDC, 2018, para. 5)

Schools should reference these guidelines when formulating plans to address food allergies and food allergy reactions while children are at educational centers. This includes the use of emergency care plans (ECP) for each student with food allergies and individualized healthcare plan (IHP). The CDC’s (2013) Voluntary Guidelines for Managing Food Allergies in Schools and Early Care and Education Programs recommends the following interventions for school nurses to help students with food allergies cope physically and psychosocially/emotionally:

- Participate in the school’s coordinated approach to managing food allergies by planning and implementing the FAMPP, supporting partnerships with staff, parents, and doctors, and help guide the policies and procedures at the school.

- Supervise the daily management of food allergies for individual students by identified students with food allergies amongst staff, maintain an ECP for each student, and assess each student’s ability to carry and self-administer an epinephrine (Epi-Pen) autoinjector if needed.

- Prepare for and respond to food allergy emergencies by developing instructions, administering medications in accordance with school policy, train and delegate to staff members, ensure standing orders are in place, contact parents and document following an emergency at school.

- Help provide professional development on food allergies for staff by staying up-to-date and teaching staff members about food allergies regularly.

- Provide food allergy education to students and parents by teaching students parents about self-management and how to detect signs/symptoms of anaphylaxis and adding food allergy material to classroom curricula.

- Create and maintain a healthy and safe school environment by assessing the school environment regularly, ensure that policies and procedures remain up-to-date with new and trending foods, work with counselor to provide emotional support to students with allergies, and promote an environment that encourage reporting of any bullying behavior (CDC, 2013, p. 59).

Treatment of Allergic Reactions

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, the nurse should educate the patient and family on food avoidance and how to respond to an allergic response should one occur. Nutritional counseling would be ideal for optimum outcomes in food allergy patients.

Reactions to food allergies vary by person. Please reference Table 1 for an exhaustive list of symptoms. Symptoms of a food allergy can include vomiting, abdominal cramping, urticaria, shortness of breath, wheezing, angioedema, syncope, or anaphylaxis leading to shock and circulatory collapse (ACAAI, 2014). Treatment of allergic responses will be based upon the severity of the reaction. According to the Mayo Clinic (2017), for minor reactions, including itching or urticaria, patients are encouraged to take antihistamines. Antihistamines are insufficient for an anaphylactic reaction.

The gold standard of treatment for anyone having a severe allergic or suspected anaphylactic reaction is the immediate administration of epinephrine (EpiPen). There are no contraindications to epinephrine (EpiPen). Concern exists regarding appropriate dosing for pediatric patients; however, the potential risks associated with underdosing epinephrine outweigh the potential risks of overdosing. The best patient outcomes result from the rapid administration of epinephrine (EpiPen). Patients with a known severe food allergy should carry two epinephrine auto-injectors (EpiPens) with them at all times, should the first dose not work properly or not relieve all symptoms. Additionally, patients or parents need to ensure the auto-injector (Epi-Pen) is not expired (ACAAI, 2014).

The recommended treatment plan for anaphylaxis due to a food allergy in a medical setting is as follows:

- Assess airway, breathing, and circulation; support all three as necessary following the American Heart Association recommended guidelines for Basic Life Support.

- Start chest compressions if necessary.

- Inject epinephrine (EpiPen) 0.3-0.5mg (0.01mg/kg for children) intramuscularly. Again, it is better to unintentionally overdose children than underdose them to ensure efficacy of the medication and decrease the response severity.

- If there is no response to the first dose of epinephrine (EpiPen), activate/call the emergency response system.

- Give 8-10L of oxygen through a facemask as needed, while monitoring pulse oximetry.

- Intramuscular epinephrine (EpiPen) can be repeated every 5-15 minutes for up to three injections if the patient is not responding.

- Establish IV access and begin infusing 0.9% normal saline as quickly as possible. In adults, 1-2L should be given in the first hour; in children, 30mL/kg in the first hour.

- Consider the administration of 2.5-5mg of nebulized albuterol in 3mL of saline for respiratory distress. Repeat as necessary every 15 minutes.

- If intramuscular epinephrine (EpiPen) is ineffective, consider giving epinephrine intravenously.

- The nurse should continuously monitor for airway complications. Consider advanced airway management as necessary.

- Optional treatments (efficacy has not been established):

- Give 25-50mg IV diphenhydramine (Benadryl) intravenously for adults, or 1mg/kg (max 50mg) for children.

- Give 10mg oral cetirizine (Zyrtec) if oral antihistamine can be safely administered. No indication to continue this medication once the reaction has resolved.

- Give 1-2mg/kg (up to 125mg) of oral or intravenous methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol). Once the allergic reaction has resolved, there is no evidence that this medication needs to be continued (NASEM, 2017).

The patient will then need to be monitored at the hospital for approximately eight hours. If the patient is successfully treated in an office setting with a single dose of epinephrine (EpiPen), the recommended time of observation is 30-60 minutes (Lieberman et al., 2015, p. 363).

Patient education should include early recognition of symptoms and immediate treatment of anaphylaxis. The nurse should review all signs and symptoms of a reaction with the patient and family. Again, the patient should be educated to carry two epinephrine auto-injectors (EpiPens) with them at all times. Patient and family education should be provided regarding when and how to administer them. If the child is in school or early childhood education, informing teachers, administration, and school staff is essential, especially if a school nurse is on staff (ACAAI, 2014).

Future Recommendations

As stated previously in this module, the prevalence of people with allergies has increased. As a medical community, we must evaluate the impacts this could have on our children and future generations’ growth, safety, and quality of life.

With the stated guideline of absolute avoidance of an allergen, there remains potential for nutritional deficiencies, particularly in children with milk, egg, and soy allergies. A systematic review analyzing the growth impact on children with multiple allergies was done by Sova et al., (2014) and suggested that having multiple food allergies early in life could impact overall growth. More research needs to be conducted; however, less growth delay was seen when patients and their families were provided with nutritional counseling (Sova et al., 2014).

In 2015, the CDC created a tool kit for professionals working with students who have food allergies or have the potential to develop food allergies. The tool kit was created utilizing the Voluntary Guidelines for Managing Food Allergies in Schools and Early Care and Education Programs as a guide. Included are short pamphlets for superintendents, principals, teachers, school nutrition professionals, school transportation staff, and school mental health professionals. Per the CDC’s (2013) Managing Food Allergies in School: The Role of School Nutrition Professionals, schools, school nurses, students, and any school personnel need to be educated to respond quickly to anyone having an allergic reaction. “Early identification of symptoms of an allergic reaction, followed by early administration of epinephrine (EpiPen) and activation of the emergency response system, could prove to be lifesaving to a child having a reaction” (p. 2).

In addition to being prepared to treat an acute allergic reaction, school personnel, parents, and children need to be educated about bullying, harassment, and teasing (Lieberman et al., 2015). A subjective study concluded that 24% of the individuals surveyed had been bullied, teased, or harassed due to their food allergies. “Of those bullied, 57% described physical events, such as being touched by an allergen or having an allergen thrown or waved at them, and several reported intentional contaminations of their food with an allergen” (Lieberman, Weiss, Furlong, Sicherer & Sicherer, 2018, p. 1). Educating parents, children, and educators on the dangers of bullying and the stressors these students already deal with due to their food allergy is imperative. Making these students feel safe and supported is of the utmost importance (CDC, 2013).

Conclusion

“Recent and ongoing research and clinical progress on assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of food allergy hold the promise of improving future practice and management strategies” (NAP, 2017, p. 22). Researchers are working to improve specific guidelines for management and educate medical practitioners, patients, families, and school personnel on early identification and treatment of an allergic response to minimize negative outcomes. “Although it is not yet possible to prevent the onset of a food allergy, due to the lack of a clear understanding of all the relevant genetic and environmental factors, or completely prevent food allergic reactions, multiple improvements could be achieved in the short term with relatively small feasible actions” (NAP, 2017, p382).

References

American Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Immunology. (2019). Eosinophilic-esophagitis. Retrieved from https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-and-treatments/related-conditions/eosinophilic-esophagitis

American Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Immunology. (2019). Food intolerance. Retrieved

from https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-and-treatments/conditions-dictionary/food-Intolerance

American Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Immunology. (2019). Food Protein Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome (FPIES). Retrieved from https://www.aaaai.org/conditions-and-treatments/library/allergy-library/food-protein-induced-enterocolitis-syndrome

American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. (2014). Food Allergy. Retrieved

from https://acaai.org/allergies/types/food-allergy

Anagnostou, K, et.al. (2014). Assessing the Efficacy of Oral Immunotherapy for the Desensitization of Peanut Allergy in Children (STOP II): A Phase 2 Randomised Controlled Trial. The Lancet, 383(9925): 1297-1304.

Boyce, J.A., Assa’ad, A., Burks, A.W., Jones, S.M., Sampson, H.A., Wood, R.A.,… Fenton, M.J. (2010).

Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. The Journal of Allergy Clinical Immunology, 126(6), (suppl):S1-58. (IV).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Managing Food Allergies in Schools: The Role of School Nutrition Professionals. Retrieved September 20, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/foodallergies/pdf/nutrition_508_tagged.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Voluntary Guidelines for Managing Food Allergies in Schools and Early Care and Education Programs. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved on from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/foodallergies/pdf/13_243135_A_Food_Allergy_Web_508.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Food Allergies in School. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/foodallergies/

Lieberman, P., Nicklas, R.A., Randolph, C., Oppenheimer, J., Bernstein, D., Ellis, A.,…Tilles, S.A. (2015).

Anaphylaxis-a practice parameter update 2015. Annals of Allergy Asthma and

Immunology, 115, 341-384. Retrieved from

https://www.aaaai.org/Aaaai/media/MediaLibrary/PDF%20Documents/Practice%20and%20Parameters/2015-Anaphylaxis-PP-Update.pdf

Lieberman, J. A., Weiss, C., Furlong, T. J., Sicherer, M., & Sicherer, S. H. (2018). Bullying among pediatric patients with food allergy. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, 105(4), 282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.07.011

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2017). Food Allergy: Diagnosis. The Mayo Clinic. Retrieved from

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/food-allergy/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20355101

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. (2017). Finding a Path to Safety in Food Allergy: Assessment of the Global Burden, Causes, Prevention, Management, and Public Policy. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/23658.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. (2018). Food Allergy. Retrieved from https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/food-allergy

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. (2011). Guidelines for the Diagnosis and

Management of Food Allergy in the United States: Summary for Patients, Families, and

Caregivers (NIH Publication No. 11-7699). Retrieved from https://www.niaid.nih.gov/sites/default/files/faguidelinespatient.pdf

Sampson, H.A., Aceves, S., Bock, S.A., James, J., Jones, S., Lang, D.,…Wood, R. (2014). Food allergy: A

practice parameter update-2014. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 134(5), 1016-1025e43. Retrieved from https://www.aaaai.org/Aaaai/media/MediaLibrary/PDF%20Documents/Practice%20and%20Parameters/Food-Allergy-A-Practice-Parameter-Update-2014.pdf

Sova, C., Feuling, M.B., Baumler, M., Gleason, L., Tam, J.S., Zafra, H. & Goday, P.S. (2013). Systematic

review of nutrient intake and growth in children with multiple IgE-mediated food allergies. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 28(6), 669-675. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0884533613505870

Vickery, B.P., Berglund, J.P., Burk, C.M., Fine, J.P., Kim, E.H., Kim, J.I.,…Burks, A.W. (2017). Early oral

immunotherapy in peanut-allergic preschool children is safe and highly effective. Journal of Allergy Clinical Immunology, 139(1): 173-181. Retrieved from

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5222765/